October 19, 2013–January 5, 2014

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

South Asian & Himalayan Art

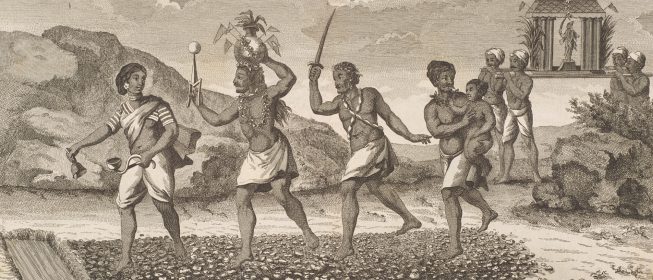

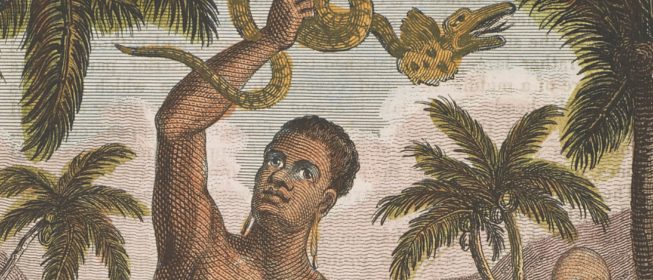

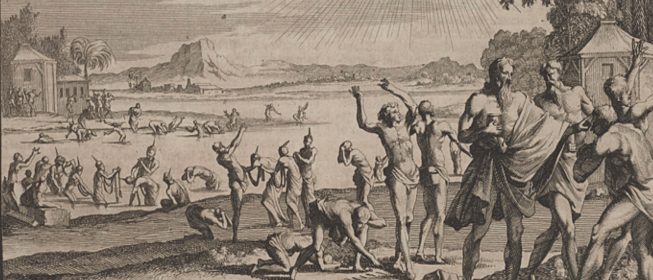

As global travel boomed from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, Europeans and Americans became increasingly fascinated with Indian culture. Merchants, soldiers, and missionaries documented their visits to India and other foreign lands in illustrated accounts. Created using such techniques as engraving, aquatint, lithography, and photogravure, these subjects and designs were easily duplicated, and copies circulated widely. Publishers regularly edited, amended, or simply reprinted them in publications as varied as atlases, memoirs, and history books.

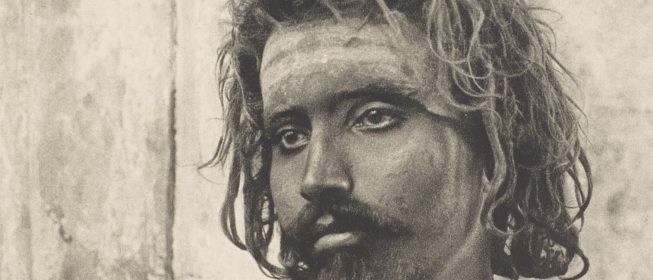

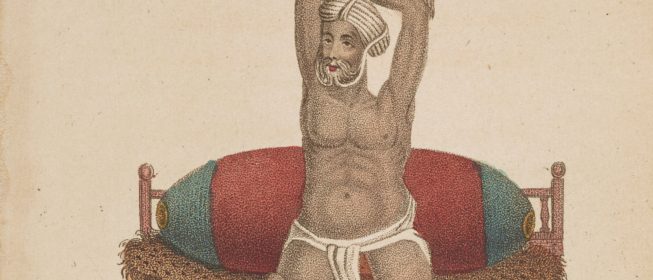

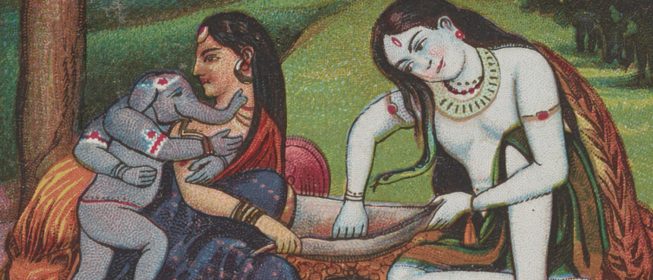

The spread of these images led to broader knowledge and interest in Indian culture—but also to the creation and proliferation of negative stereotypes. Ascetics, or religious figures who renounce material comforts, were depicted over the years as supernatural beings, devout penitents, militants, tricksters, and beggars. Religious ceremonies were interpreted within a Christian framework instead of a Hindu one, leading to misconceptions of devotees as sinners or fanatics. With the aid of Indian art, deities were catalogued as lovers, drug users, and creators of the cosmos, which fed generalizations of India as a sensual, spiritual land.

The fifty artworks in Strange and Wondrous, from the encyclopedic Robert J. Del Bontà collection, show how certain ascetics and Hindu practices became emblems for all that Europeans and Americans found exotic, repulsive, or remarkable in India. By tracing how these images were interpreted and reproduced over time, the exhibition also demonstrates how perceptions of Indian culture shifted through the centuries, from the Enlightenment to the colonial period and Christian missionary movement, and into modernity. Together these prints reveal structures of the European and American imagination as much as they encapsulate conceptions of India.

History of a Print

The location of publication

The fifty prints in Strange and Wondrous can be mapped by space, language, and time. Images and texts were copied primarily in Europe but also in India and North America. They were translated between Latin, Dutch, English, French, German, and Italian, and consistently printed and reprinted from the sixteenth to the twentieth century.

Zoom into the map and click the pinpoints to compare when, where, and in what language the prints were published, and to see how subjects and designs moved between cities.

Dr. Robert J. Del Bontà

A polymath scholar, curator, collector, and jeweler, Dr. Robert J. Del Bontà began to collect prints related to India while completing his doctorate in South Asian art history at the University of Michigan in the 1970s. His wide-ranging collection contains more than two thousand loose prints and thousands more within books. It also spans genres such as Indian calendar prints, ephemera, painting, and sculpture, and British Raj-era publications; and subjects such as ornament, flora and fauna, and the emphasis of this exhibition, Indian ascetics, deities, and religious ceremony.

In his collecting practices, Del Bontà traces how Europeans and Americans constructed knowledge about India through prints. He focuses on the curious mixture that resulted when events witnessed “up close” in India were published “from afar,” in Europe or America. A careful attention to prints made “up close” allows Del Bontà to see how Indian and European texts and visual resources influenced travelers’ on-the-spot observations in India. By viewing prints created “from afar,” he examines how printmakers and publishers fluent in European artistic conventions adapted travelers’ in-person observations, always adding a dash of fantasy. He further tracks how compositions were copied and altered over long stretches of time, inspiring questions about publication practices as well as the accuracy of these images.

Above all, he considers these prints a rich resource for education. A promised gift, the objects in this exhibition will be available in the National Museum of Asian Art Archives for use in studying and interpreting the long history of Europeans and Americans attempting to document, understand, and evaluate Indian culture through print.

Bibliography

Bloch, Esther, Marianne Keppens, and Rajaram Hegde. Rethinking Religion in India: The Colonial Construction of Hinduism. London: Routledge, 2010.

Cohn, Bernard S. “The Past in the Present: India as a Museum of Mankind.” In History and Anthropology 11:1 (1998), 1–38.

Del Bontà, Robert J. “From Herodotus Onwards: Descriptions of Unidentified Jains.” In Jaina Law and Society, edited by Peter Fluegel. Routledge: 2013.

Del Bontà, Robert J. “India Viewed from Afar: the Engravings of Bernard Picart.” University of Michigan Museum of Art, December 6, 2003–March 14, 2004.

Diamond, Debra, ed. Yoga: The Art of Transformation. Random House, 2013.

Hardgrave, Robert L. Portrait of the Hindus: Balthazar Solvyns & the European Image of India. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Hunt, Lynn, Margaret Jacob, and Wijnand Mijnhardt. The Book that Changed Europe: Picart and Bernard’s Religious Ceremonies of the World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Lach, Donald. Asia in the Making of Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965–93.

Lightbown, R. W. “Oriental Art and the Orient in Late Renaissance and Baroque Italy.” In Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 32 (1969), 265–79.

Marshall, Peter. The British Discovery of Hinduism in the 18th Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970.

Mitter, Partha. Much Maligned Monsters: History of European Reactions to Indian Art. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977.

Narayan, Kirin. “Reflections of the Field at Home: American Representations of Hindu Holy Men in the 19th and 20th Century.” In Cultural Anthropology 8:4 (November 1993), 476–509.

Oddie, Geoffrey A. Popular Religion, Elites, and Reforms: Hook-Swinging and its Prohibition in Colonial India, 1800–1894. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors, 1995.

Pinch, William R. Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Schwab, Raymond. The Oriental Renaissance: Europe’s Rediscovery of India and the East, 1680–1880, translated by G. Patterson-Black and V. Reinking. New York: Columbia University Press, 1984.

Singleton, Mark. Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Sloan, Kim, ed. Enlightenment: Discovering the World in the Eighteenth Century. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2003.

Sweetman, Will. Mapping Hinduism: ‘Hinduism’ and the Study of Indian Religions, 1600–1776. Halle: Franckesche Stiftungen, 2003.

White, David Gordon. Sinister Yogis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Detail: “Îshâna ou Shiva” (Shiva). Robert J. Del Bontà collection, E563

- Jump To...