Taking many forms and serving many functions, ink is an enduring medium that still surrounds us today. Learn how different kinds of ink are made as well as how inks have had functional and artistic uses across cultures represented in the museum’s collections.

We use ink all the time but rarely stop to think about where it comes from and how it’s made. Ink is what many people use to write or draw with. Printing, whether through manual processes or using modern technology such as ink-jet printers, is carried out using ink. Painting with ink has a long history, but we often think of paint as something different than ink. In East Asia especially, no line is traditionally drawn between ink and paint, as both painting and writing were carried out using a brush. The same type of ink used by schoolchildren is used by master calligraphers and the most highly skilled painters, although of different qualities. If we define ink as a substance that comes from a pen or printer, it can come in any color, and its defining feature is that it dissolves into a liquid. But historically, there are a few inks that were commonly used.

Making and Using Ink

One of the most common writing inks is iron gall ink, which was used for centuries in the Middle East and Europe and can be easily made from an iron salt and oak galls. When written with iron gall, ink is often a dark color, but it fades to the brown tones of rust (chemically, it forms the same compounds as rust). Several manuscripts in the museum’s collections were written with iron gall ink.

-

Open ImageWashington Manuscript I - Deuteronomy and Joshua (Codex Washingtonensis)

-

Open ImageWashington Manuscript II - The Psalms (Codex Washingtonensis)

-

Open ImageWashington Manuscript III - The Four Gospels (Codex Washingtonensis)

-

Open ImageWashington Manuscript IV - The Epistles of Paul (Codex Washingtonensis)

-

Open ImagePartial Psalter, 126 fragmentary leaves

-

Open ImageCanon Table from a Gospel manuscript

The most common inks in Asia are a carbon-based black ink. In Central and South Asia, this type of ink would frequently be bound with a plant gum; in East Asia, it would be bound with a protein-based animal skin glue. Both inks are soluble in water, making them easy to use. Unlike iron gall ink, carbon-based inks are still very common today. Inks used in laser printers and photocopiers, the colorant used in most black plastics, and even the pigment used in car tires are all made from carbon-based black pigments. In recent times, these carbon-based black pigments are specially made soots called carbon black, but historically they were made from burning vegetable or lamp oils and collecting the soot (lampblack). In East Asia, they were made by burning resinous pinewood and collecting the soot that was produced in special chimneys.

Black carbon-based ink is a highly versatile pigment with a small, regular particle size. This means it can be mixed and graded with a high degree of precision and can be used to create specific effects. Adding colors can provide further layers of symbolic meaning and decorative effect.

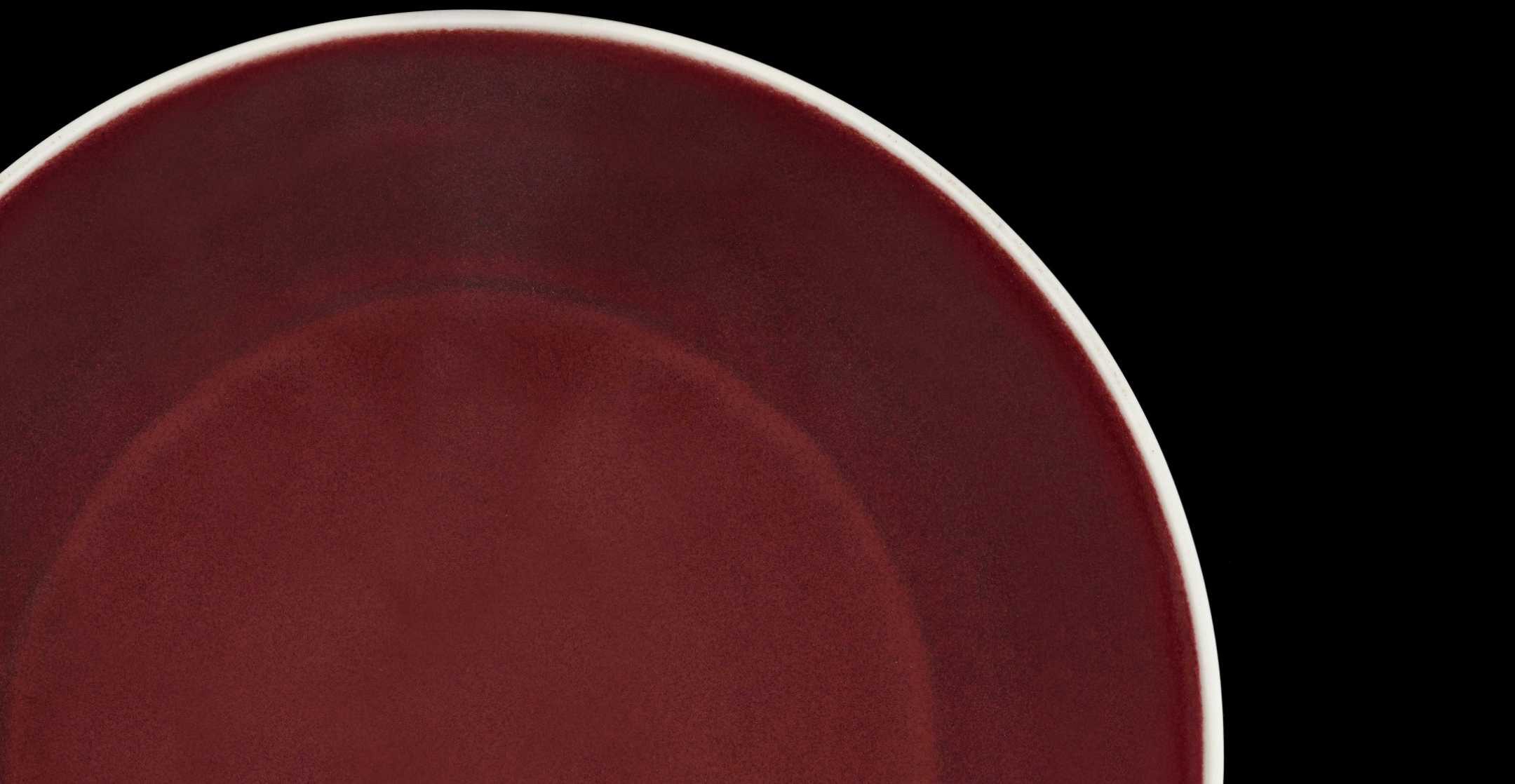

Throughout East Asia, ink was historically manufactured and traded in solid form, either as a stick or cake. It is made of pine soot or lampblack that is mixed with glue and pressed in molds to create a variety of shapes and sizes. To produce liquid ink, the artist grinds an inkstick with water on the hard surface of an inkstone. The resulting liquid ink varies in blackness according to the amount of water added. Inksticks are often decorated with molded designs or texts and are painted with gold or other colors. Artists use an inkstone both as a surface for grinding the solid ink into liquid form and as a reservoir to hold the liquid ink once it is made. The surface of an inkstone should be fine and smooth, yet abrasive enough for grinding the ink quickly.

-

Open ImageInkstick

-

Open ImageInkstick

-

Open ImageInkstick in a brocade-covered box

Ink has also been widely used in East Asia to transfer attractive texts and images from durable media, like stone and metal, to paper, which is much more portable. Conventionally called “rubbings” in English, these Chinese, Korean, and Japanese reproductions aren’t usually made by rubbing dry ink over a paper-covered surface but instead involve the use of wet ink, dampened paper, and a diluted natural adhesive. In the classic technique, moistened paper is applied to the desired surface; with gentle pressure, the material stretches slightly, accommodating raised or sunken portions of the durable surface below. Extraction of excess moisture promotes the tight adhesion of the paper and ensures the accurate transfer of the surface profile, almost like embossing. After the paper is thoroughly dry, light applications of ink using a cloth tamper darken elements that are raised and leave sunken areas white in reverse, thus producing a black-and-white reproduction of a passage or pattern.

Writing with Ink

While today it may feel unremarkable to pick up a ballpoint pen and jot down notes, writing with ink is historically far more complex. Materials were made with precision, long traditions of training in calligraphic techniques were developed, and writing and literacy were often wrapped up in questions of social status and class.

Although the development of major Chinese calligraphic scripts was virtually complete by the fourth century, the art of calligraphy continued to evolve over the millennia. Master calligraphers with years of training and dedicated practice were recognized for their personal styles, and later generations of artists often adapted brushstrokes and designs to their own style. This stylistic evolution of scripts continues to enliven Chinese calligraphy to the present day.

Calligraphy was an important mark of personal learning and aesthetic sensibility in Japan. Portable, lacquered wood boxes were designed to hold an inkstone and water dropper in the base, with trays to hold writing brushes and solid ink sticks. Inkstone boxes (suzuribako) could be easily carried to a pleasant location, even outdoors in fine weather, to write correspondence, diary entries, or poetry.

Zhu Da won the praise and admiration of his contemporaries as a calligrapher; calligraphic techniques and the effectual manipulation of brush and ink were also the foundation of his approach to painting. He developed a distinct and immediately recognizable personal style in both calligraphy and painting. And in both, the development of his brushwork generally followed the same path and direction: sharp, angular, and full of personal expressiveness in his early years, mellow and softer in his later years and characterized by a mature subtlety.

Painting and Drawing with Ink

Different schools of painting existed in China, the scholar-painters of Song-dynasty China generally preferred ink-based paintings over the more colorful, pigment-filled paintings produced historically and at the painting academy. Chinese painting manuals and commentaries from the Song and Yuan dynasties rarely mention pigments, possibly because it was assumed a painter’s skill shouldn’t depend on the use of colors.

“Grasses and trees spread forth their glory without depending upon cinnabar and azurite; clouds and snow whirl and float aloft, and are white with no need for ceruse. Mountains are green without needing malachite, and the phoenix is iridescent without the aid of the five colors. For this reason one may be said to have fulfilled one’s aim when the five colors are all present in the management of ink. If one’s mind dwells on the five colors, then the images of things will go wrong. In painting things one should especially avoid a meticulous completeness in formal appearance and coloring, and extreme carefulness and detail that display skill and finish.”

Japanese artists are known for using media appropriate for the subject matter. Images depicting traditional Japanese narrative tales were typically rendered in opaque colors with outlines created in ink and later obscured by color overlay. Ink monochrome was closely associated with Chinese styles, particularly those transported to Japan via Zen Buddhism. Ink-based forms created with modulated strokes and layered washes suggested introspection and spiritual exploration.

Watch how the different elements of an ink painting combine to create a whole image:

Video | “How does an ink painting come together?” | View on YouTube

The expressive potential of ink painting was channeled by artists who developed their own techniques for painting with ink.

This magnificent, large-scale, abstract form of a crane is rendered with versatile brushwork entirely in tones of ink. An unusually striking technique of building forms with brushstrokes and leaving unpainted areas between depicts the gray feathers of the crane. Wet and dry strokes suggest plumage. Crisp, dark contours on the rocks and in the feathers of the crane accentuate the composition.

In his application of the tarashikomi technique—random pools of pigment and ink—Sōtatsu subtly subverted the tradition. He used ink to depict the ordinary subjects of everyday life—puppies and plants—in a style that took on an allusive ambiguity. Instead of the solid, opaque colors traditionally associated with narrative painting, Sōtatsu used pooled ink and randomly changing color fields to indicate the underlying Buddhist theme: the unreliability of the visual world.

Seitei is best known for his illustrated book designs, particularly those of birds and flowers. He provided drawings for a number of multivolume illustrated books that were partially intended as guides for aspiring painters to learn brushwork techniques but which could also be enjoyed for their visual qualities alone. In this example, a group of pigeons on an autumnal branch presses together for warmth, their swelling mass literally bursting from the boundaries of the page margins.

A broadly stroked, curvilinear grapevine stretches across the surface of this eight-fold screen. Serrated grape leaves and curving tendrils are summarily rendered in light ink tones, with veins added in darker ink lines. Clusters of grapes in scorched black ink serve as powerful visual accents, punctuating the undulating rhythm of the vine. The composition does not match seamlessly, and it is possible that the panels may have been trimmed or reordered at one time, making a full understanding of its original state more difficult.

The artist’s inscription in the lower right of the seventh panel provides the sobriquet Nanggok, a cyclical date, and a reference to the ninth month, in autumn. Nanggok is believed to have been used by the artist Choe Sokhwan, who was born in 1808 (date of death unknown) and was known for his studies of grapes. Another painting of grapes by the same artist bears the date 1897, so the cyclical date written on this screen probably corresponds to 1883.

Learn about several different ink painting techniques:

Video | “Sōtatsu’s Methods: The Visibility of Craft” | View on YouTube

Keep Exploring

Explore All Pieces in this Section

Washington Manuscript I - Deuteronomy and Joshua (Codex Washingtonensis)

-

Geography

Egypt

-

Material

Ink on parchment

-

Accession

F1906.272

Washington Manuscript II - The Psalms (Codex Washingtonensis)

-

Geography

Egypt

-

Material

Ink on parchment

-

Accession

F1906.273

Washington Manuscript III - The Four Gospels (Codex Washingtonensis)

-

Geography

Egypt

-

Material

Ink on parchment

-

Accession

F1906.274

Washington Manuscript IV - The Epistles of Paul (Codex Washingtonensis)

-

Geography

Egypt

-

Material

Ink on parchment

-

Accession

F1906.275

Partial Psalter, 126 fragmentary leaves

-

Geography

Fayyum, Egypt

-

Material

Ink on vellum

-

Accession

F1908.32

Canon Table from a Gospel manuscript

-

Geography

Armenia

-

Material

Opaque watercolor, ink and gold on parchment

-

Accession

F1947.4

Inkstick

-

Period

Qing dynasty

-

Geography

China

-

Material

Soot and glue with gold pigment

-

Accession

F1983.12.25

Inkstick in a brocade-covered box

-

Period

Qing dynasty

-

Geography

China

-

Material

Inkstick: soot, animal glue with gilding; box: paper with silk brocade

-

Accession

F1980.93.3a-b

Writing box (suzuribako) with scene from Tale of Genji, Chapter 14

-

Period

Edo period

-

Geography

Japan

-

Material

Lacquer on wood with gold and silver inlay; gilt silver; stone

-

Accession

F1991.9a-h

Buddhist stele (a) with an attached rubbing (b)

-

Period

Tang dynasty

-

Geography

China

-

Material

Gray stone; ink on paper

-

Accession

F1980.30a-b

Couplet in running script 行書五言對聯

-

Period

Qing dynasty

-

Geography

China

-

Material

Pair of hanging scrolls; ink on paper

-

Accession

F1998.39.1-2

Cranes, one of a pair

-

Period

Edo period

-

Geography

Japan

-

Material

Ink on paper

-

Accession

F1997.25.1a-f

Dragons and Clouds 雲龍図屏風 (左隻)

-

Period

Momoyama or Edo period

-

Geography

Japan

-

Material

Ink and pink tint on paper

-

Accession

F1905.229

Seitei kachō gafu 省亭花鳥画譜

-

Period

Meiji era

-

Geography

Japan

-

Material

Woodblock printed; ink and color on paper; paper covers

-

Accession

FSC-GR-780.759.1-3