May 21–October 30, 2022

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery | Gallery 22

-

Collection Area

Korean Art

Roof tiles made of fired clay are key elements of traditional Korean architecture. They not only protected wooden structures from the weather; they also carried aesthetic value and symbolic meaning. One special type of ornamented roof tile is the focus of this exhibition. Called chimi in Korea, these impressive features crowned both ends of the main roof ridge of prominent buildings. In addition to protecting and embellishing building peaks, they were believed to ward off evil.

While the ancient wood frame buildings they adorned are long gone, clay roof tiles, including chimi, have survived more than one thousand years. This exhibition features three chimi unearthed from the sites of two Buddhist temples and one palace complex dating to the Three Kingdoms (Baekje) and Unified Silla periods. Also included are round roof tile ends excavated at the same sites. Together, these artifacts reveal hidden stories of the ancient architecture of Korea.

Most of these works have never been exhibited outside Korea.

We thank our colleagues at the National Museum of Korea for sharing their research and for facilitating this exhibition.

Explore this Exhibition

Object Gallery

Roof ridge ornament (Chimi)

Korea, Three Kingdoms, Baekje, Sabi period (538–660)

Excavated from the temple site at Mount Buso, Buyeo, South Chungcheong province

Earthenware

Roof ridge ornament (Chimi)

Korea, Three Kingdoms, Baekje, Sabi period (538–660)

Excavated from the Mireuksa temple site, Iksan, North Jeolla province

Earthenware

Roof ridge ornament (Chimi)

Not restricted to Buddhist temples, roof ridge ornaments also graced secular palaces. This chimi was excavated from Wolji, a royal garden pond at the site of the East Palace in the capital of the Silla kingdom. Its undecorated body and dramatically protruding round spine in front of the wings are characteristics of chimi dating to the Unified Silla kingdom.

Roof tile end

Korea, Three Kingdoms, Baekje, Sabi period (538–660)

Excavated from the Mireuksa temple site, Iksan, North Jeolla province Earthenware

Diam: 13 cm

Iksan National Museum, mireuk 9760

© Iksan National Museum

This round roof tile end is adorned with a molded lotus design. The central circular pod contains seven lotus seeds, and the interior of each petal is decorated with a sprouting seed. The lotus—a symbol of purity in Buddhism—was the most popular motif across both secular and religious architecture during the Three Kingdoms period.

Image 1 of 5

Tile with temple in a landscape

Korea, Three Kingdoms, Baekje, Sabi period (538–660)

Excavated from the temple site at at Oe-ri, Buyeo, South Chungcheong province

Earthenware

H x W x D : 29 .3 x 29 .1 x 4.5 cm

National Museum of Korea, bon 13972

© Buyeo National Museum

This clay tile is decorated with a landscape scene featuring a boulder-filled stream and groups of three-peaked mountains covered in pine trees. A closer examination of the lower central mountain reveals a building with two standing ridge ornaments on its roof. This pictorial evidence suggests the use of roof ridge ornaments in their time. If you look in the lower right-hand corner, you can see a priest walking toward the retreat. This tile also represents an early stage of landscape representation in Korea.

Image 2 of 5

Rafter end tile

Korea, Three Kingdoms, Baekje, Sabi period (538–660)

Excavated from the Mireuksa temple site, Iksan, North Jeolla province

Earthenware with green glaze

Diam: 15 cm

Iksan National Museum, mireuk 6357

© Iksan National Museum

This rafter end tile is adorned with seven petals surrounding the central pod along with seven lotus seeds, which is a much less common design than eight-petal versions. In addition to their aesthetic qualities, rafter end tiles would have been nailed to the ends of wooden rafters through the square holes in their centers to protect the timber from decay. Unearthed at the site of a Baekje temple founded during the reign of King Mu (reigned 600–41), it represents the earliest use of green glaze in the production of roof tiles in Korea.

Image 3 of 5

Brick with dragon, buildings, and landscape

Korea, Unified Silla kingdom (676–935)

Excavated from Jungsan-dong, Ulsan

Earthenware

H x W x D: 6.9 x 15.8 x 11.6 cm

Gyeongju National Museum, gyeongji 4655

© Gyeongju National Museum

This clay brick renders structural elements of ancient wooden buildings in great detail. The front façades of the buildings feature columns, brackets, and a tiled roof. Roof ridge ornaments are also clearly visible at both ends of the main peak. The buildings float on clouds against a distant landscape that is represented by horizontal lines and triangular mountains, suggesting the structures may be heavenly palaces in a Buddhist paradise.

Image 4 of 5

Roof tile end

Korea, Three Kingdoms, Baekje, Sabi period (538–660)

Excavated from the Mireuksa temple site, Iksan, North Jeolla province Earthenware

Diam x L: 14 x 39.4 cm

Iksan National Museum, mireuk 5916

© Iksan National Museum

Round roof tile ends like the one seen here capped the end of convex roof tiles at the eaves above the rafters, where they were intended to direct water off the roof. A notable feature of this roof tile end is the attached convex roof tile that has survived intact. Excavated at the site of a Baekje temple called Mireuksa, this type of roof tile end with six-petal lotus design was found in the greatest number, suggesting they were produced at the time of the temple's foundation.

Image 5 of 5

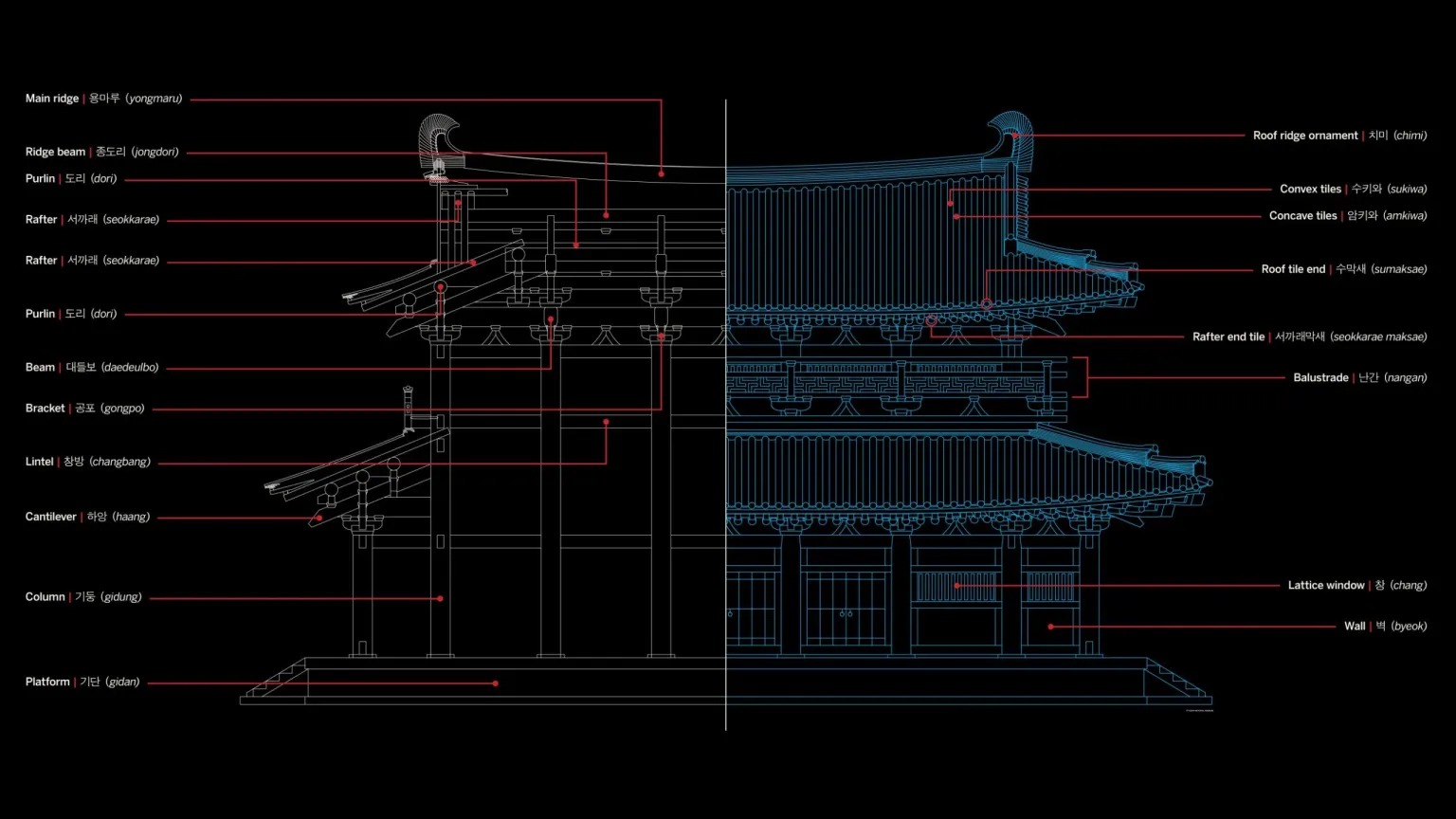

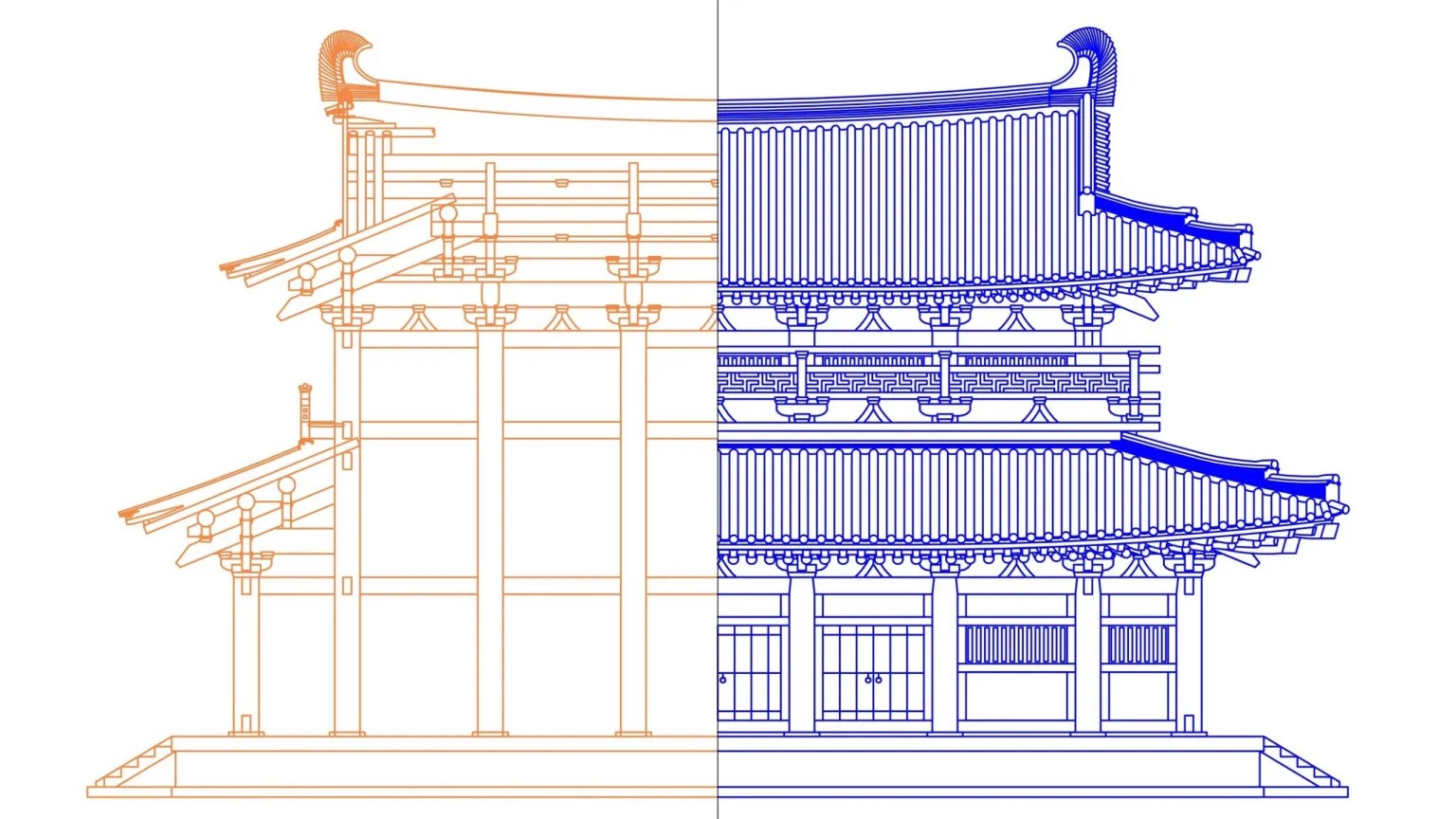

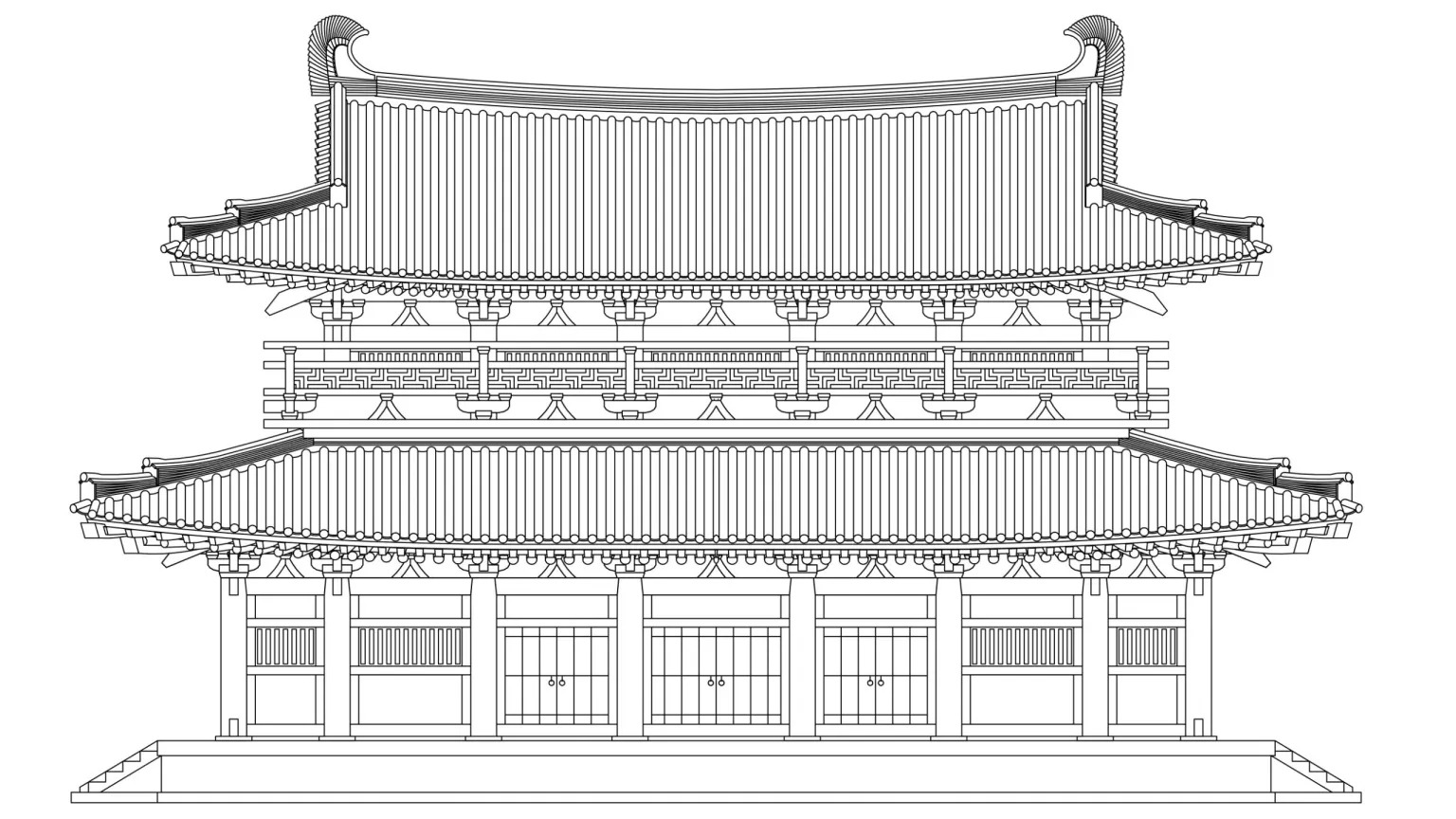

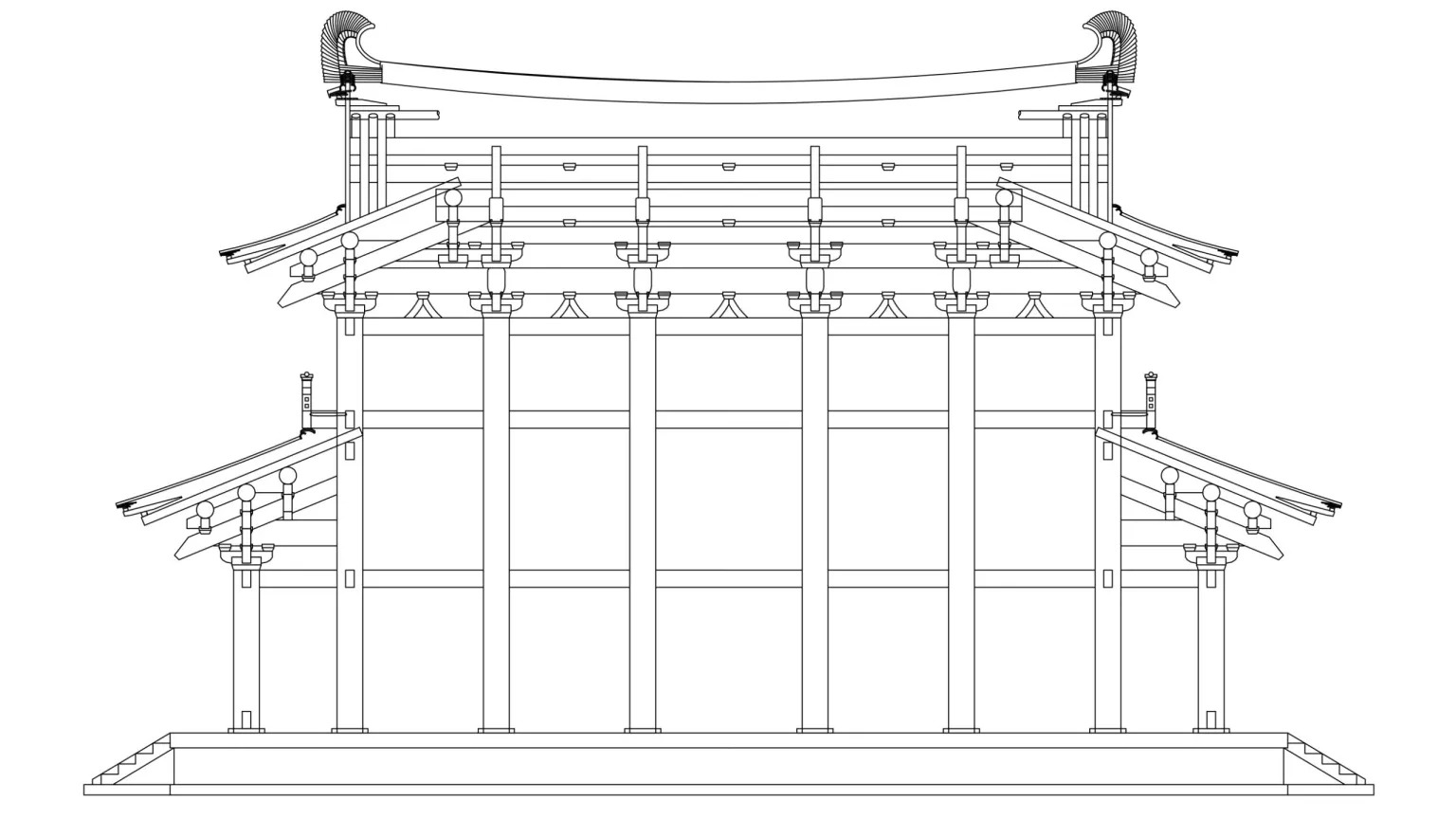

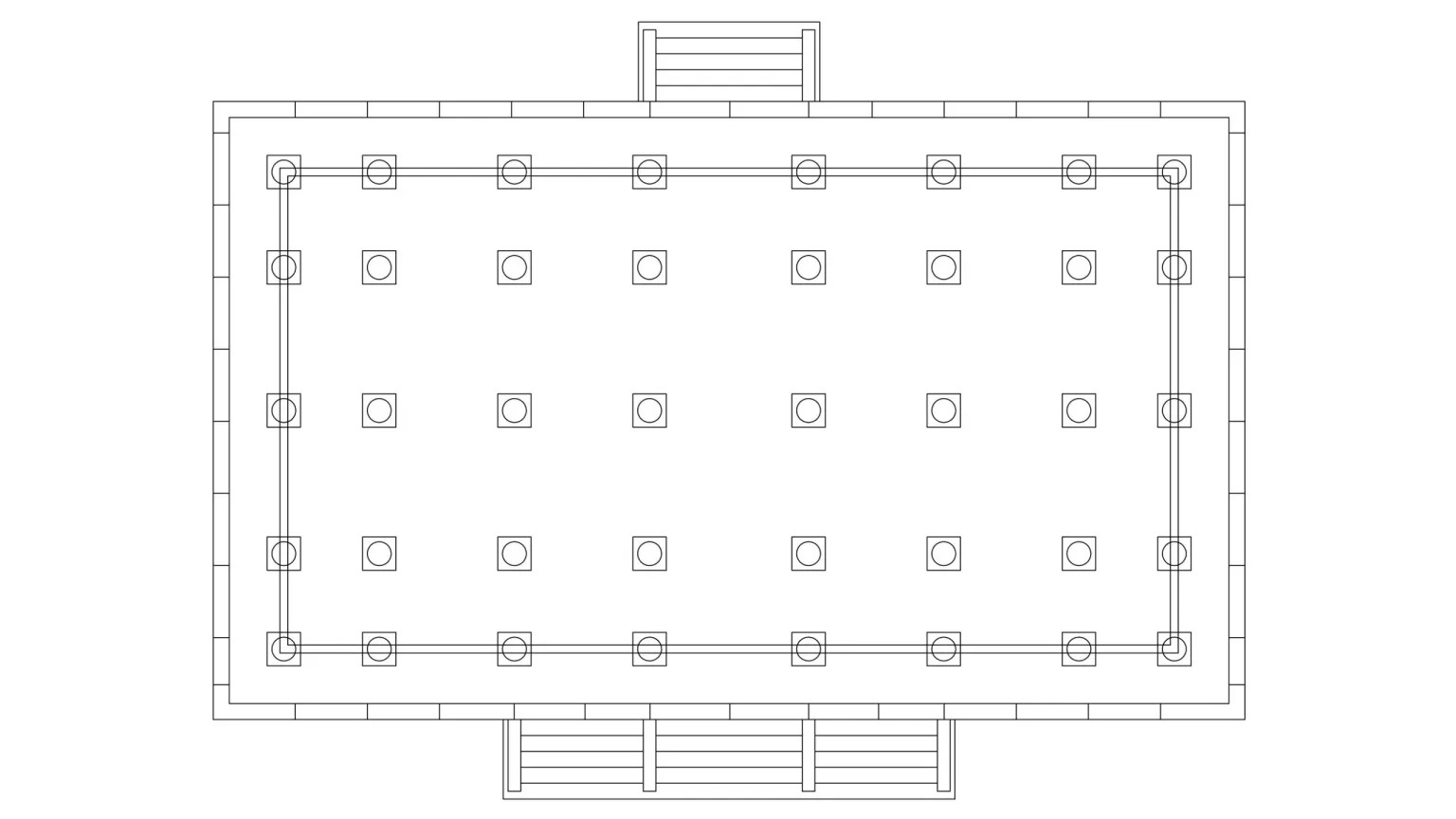

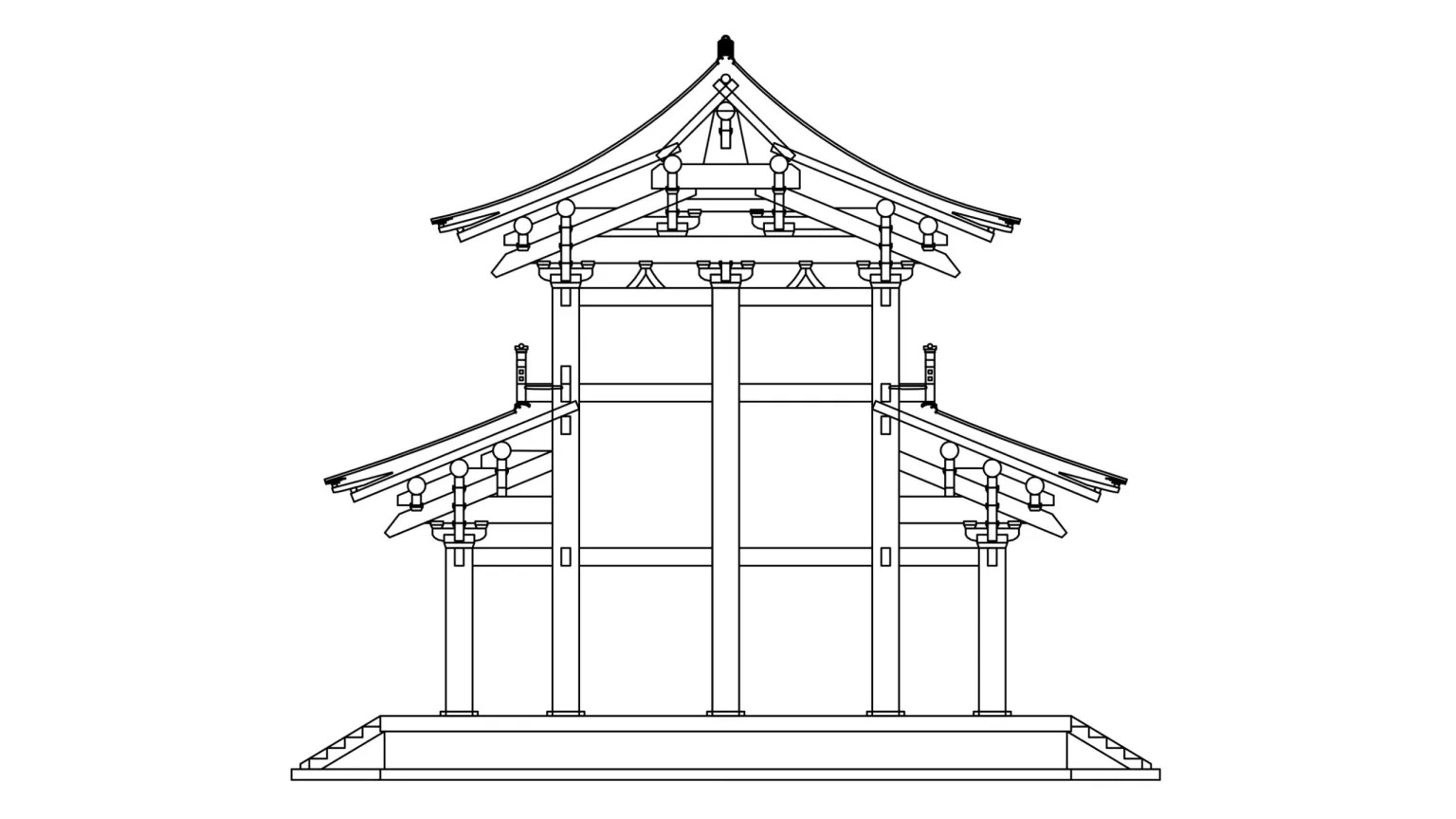

Architectural model and drawings

Ceramic tile roofs are prominent aspects of East Asian architecture. The kiln-fired interlocking pieces create a waterproof cover that protects less durable structural materials like wooden ridges, rafters, beams, and columns. This construction practice first developed in China and came to Korea in the fourth century with Buddhism. Across East Asia, similar building principles were used for both religious and secular structures. Although the tiles featured in this show have survived at archaeological sites, their buildings have not.

Fundamental elements of a traditional timber-frame building include a ceramic tile roof, wooden supporting framework, and stone foundation. The architectural model and its drawings shown here are reconstructions based on the remains of a large-scale building in Iksan that is believed to have been a main palace hall of the Baekje kings. Rendered at a scale of 1:50, the actual construction measured over 115 feet wide and had an area of almost 7,000 square feet. Names of principal parts of a traditional building are also indicated on the drawing.

Image 1 of 11

Image 2 of 11

Image 3 of 11

Image 4 of 11

Image 5 of 11

Image 6 of 11

Image 7 of 11

Image 8 of 11

Image 9 of 11

Image 10 of 11

Image 11 of 11

Videos

Ornamented Tiles at the Seventh-century Buddhist Temple Mireuksa | This video shows the relative scale and layout of buildings at the Buddhist temple site called Mireuksa, in addition to how three types of ornamented ceramic tiles were used at the temple. © Iksan National Museum | View on YouTube

Exhibition Highlights | View on YouTube

Meditation & Mindfulness | View on YouTube

Essays

-

Buddhist Architecture in Korea

KIM Bongryol, Korea National University of Arts

-

Chimi: Roof Ridge Ornaments of the Three Kingdoms Period

KIM Dongha, Gyeongju National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage

-

Japan's Asukadera Videwed Through the Lens of the Korean Baekje Kingdom Temple Site of Wangheungsa

LEE Byongho, Gongju National University of Education

© Baekje Cultural Land in Chungcheongnam-do, © Buyeo Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, © Iksan National Museum

- Jump To...