October 11, 2014–June 7, 2015

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

Arts of the Islamic World

Unearthing Arabia: The Archaeological Adventures of Wendell Phillips traces for the first time the extraordinary archaeological expeditions of Wendell Phillips and his intrepid team. Much of their work was conducted in 1950 and 1951 at Timna, the ancient capital of the kingdom of Qataban, and at nearby Hajar bin Humeid, which “in antiquity stood at the fork in the incense road,” as Phillips observed. The objects are organized according to the different sites that the team excavated: Timna and its South Gate, the House Yafash, the monumental temple, and the cemetery located just outside the city limits, as well as the site of Hajar bin Humeid. Unearthing Arabia concludes with a discussion of more recent excavations in Marib, conducted from 1998 to 2006 and supported by the American Foundation for the Study of Man and its current president, Merilyn Phillips Hodgson. Wendell Phillips’s own words and lively descriptions of events convey the excitement, drama, and challenges of this expedition more than sixty years ago.

Unless otherwise indicated, all of the objects shown here are from the archaeological expeditions led by Wendell Phillips in modern-day Yemen in 1950 and 1951. All of the expedition photographs are courtesy of the American Foundation for the Study of Man. All quotes are from Wendell Phillips, Qataban and Sheba: Exploring the Ancient Kingdoms on the Biblical Spice Routes of Arabia (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1955).

Excavations: Awam Temple

When Wendell Phillips left for Marib in northern Yemen in the spring of 1951, he did so “with such feelings of elation and excitement as I have never had in my life, before or since.” The focus of this expedition was the Awam Temple (Mahram Bilqis), the largest of its kind on the Arabian Peninsula. According to legend, Marib was the capital of the Sabaean kingdom, ruled by the biblical Queen of Sheba. Sabaean inscriptions refer to it as the Temple of Almaqah, the moon god who was the principal deity at Marib.

At that time only the tops of the temple’s eight massive pillars and the upper sections of an oval wall remained visible. Workers painstakingly removed the windblown sand before the expedition team uncovered a large hall lined with monumental pillars, stairways, impressive bronze and alabaster sculptures, and numerous inscriptions.

Unfortunately, tribal tensions brought the Marib expedition to a sudden halt. In their haste to leave, Phillips and his colleagues had to abandon all their equipment and archaeological discoveries. The team’s written records were later incorporated into scholarly publications, including an archaeological report published by Johns Hopkins University Press. Phillips always hoped to return to Marib, but his untimely death in 1975 prevented that wish from becoming a reality.

Almost a half-century later, in 1998, the government of Yemen invited Merilyn Phillips Hodgson to continue her brother’s work in Marib. The next year, more than fifty workmen and an international team of archaeologists, epigraphists, architects, and geomorphologists once again began to work on this important site. For the first time, the interior of the oval precinct walls was excavated to a depth of sixteen feet, and new inscriptions were discovered. The team’s surveyor generated digital topographic plans and three-dimensional models of the site, which will greatly aid future expeditions. During nine seasons of excavations at Marib, the team unearthed one of the most significant architectural complexes and religious centers of ancient Arabia.

I’m proud to continue my brother’s work. I went to Yemen to fulfill Wendell’s unfinished dream. After my first excavation at Marib, it became my passion.

Merilyn Phillips Hodgson graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, with a bachelor’s degree in art. It was not until after the premature death of her brother and mentor, Wendell Phillips, that she decided to become involved with the American Foundation for the Study of Man (AFSM) and to continue his work. She now serves as the president of AFSM.

The first archaeological expedition of the newly reformed AFSM occurred in 1982 at the Wadi al-Jubah. Completed five years later, it resulted in the publication of a series of five scientific volumes. It was a proud moment in 1998 when the Foundation returned to the Awam Temple in Marib, Yemen, a site Wendell and his team had to abandon back in 1952. As of 2006, AFSM has conducted eight field seasons at Marib and has made major strides in adding to the knowledge and understanding of this important site and of Yemeni archaeology in general.

Image 1 of 4

In his book, Wendell Phillips describes his sense of purpose in leading an excavation at Marib. “We were standing were no American or Englishman had ever stood and where no non-Moslem had been, to our knowledge, since 1889. We looked at the buried ruins of what had once been the largest and richest of the ancient cities of South Arabia, the center of a great culture almost three thousand years ago. And we were going to dig away the sand that covered it, push aside the veil of secrecy that had for so long hidden most knowledge of that civilization. We were going to excavate at this prize site where no scientific excavation had even taken place. If you had told me that the mound in front of us contained a gold mine at which I could help myself, I could not have been as excited, as deeply moved as I was by the prospect before us.”

Image 2 of 4

Wendell Phillips and his team excavated the great walled enclosure of Mahram Bilqis, the ancient Temple of Awam, dedicated to the moon god Almaqah. Tribal unrest in the area halted their efforts in 1952. Decades later, the government of Yemen invited Merilyn Phillips Hodgson and AFSM to continue her brother’s work.

Image 3 of 4

After nine seasons of digs, AFSM has unearthed the extensive temple complex and other structures at Marib. The site had been buried under sand for centuries before Wendell Phillips and his team began their excavation there in the early 1950s.

Image 4 of 4

Excavations: Hajar bin Humeid

Human beings have a strange habit of sticking to the same spot when they build a city.… This habit makes it convenient for archaeologists, who can dig down through one ancient mound and study the remains of civilization after civilization.

When Wendell Phillips and William Albright, his chief archaeologist, first studied the large oval-shaped mound in the Wadi Beihan, they focused on a naturally eroded vertical gash on the western side. That site in the wadi—an Arabic term for valley or riverbed—became the center of their excavations in 1950 and 1951. They hoped that within the scarp they would uncover pottery and layers of human occupation that would help them in reconstructing the consecutive town sites down to the original bedrock.

Such an undertaking, however, was not without its challenges. Once a layer of occupation was removed, the material remains could not be restored or replaced. Phillips explained: “All shovel work must be under the supervision of a man who knows where to dig, how deep, what to look for, and above all, when to stop.”

By the end of the second season of excavating the sixty-foot-tall multilevel site, archaeologist Gus Van Beek established a dating sequence based on eighteen strata. Through their work, the archaeologists determined Hajar bin Humeid had been located on the caravan routes to the Mediterranean. Relatively modest in scale, the city served the Qataban kingdom by collecting customs from all caravans traveling through the Wadi Beihan area.

Excavations: Timna

Timna (or Tamna‘) was the capital of Qataban, one of the five kingdoms that included Ma’in, Saba, Himyar, and Hadhramaut in southern Arabia. According to the Roman author Pliny the Elder, who died in 79 CE, Timna was a bustling city with some sixty-five temples. For hundreds of years it maintained a monopoly on the cinnamon trade and levied taxes on caravans carrying incense. The city flourished as Qataban’s main commercial and religious center from the early seventh century BCE until the last quarter of the first century CE. Excavations conducted by AFSM suggest a major fire at Timna forced its inhabitants to abandon the city sometime in the first century CE. Commercial and religious activities apparently were transferred to nearby Hajar bin Humeid, where they continued for at least another century.

In 1950 and 1951, Wendell Phillips and his team succeeded in excavating several important sites at Timna. These include its South Gate, several private residences, a large structure that the team identified as a temple complex to Athtar (Venus), and the cemetery, locally known as Haid bin Aqil, just outside the city walls.

Timna Cemetery

Long-buried objects were unearthed in the cemetery at Timna. Wendell Phillips observed that these alabaster objects were “standing exactly as they were before excavation in the antechamber to a tomb at the Timna cemetery. A few minutes before this picture was taken these unsuspected objects were completely covered by the debris of two thousand years.”

Image 1 of 14

Statue of a Seated Woman

Carved of luminous alabaster, this seated female figure with clinched fists is a fine example of the funerary statues found at the cemetery near Timna. Her stiff torso is disproportionate to her delicate face with its deep-set eyes, which were originally inlaid with either glass or lapis lazuli. As is typical of the South Arabian sculptural tradition, the idealized facial features still lend a sense of individuality to the figure.

Statue of a seated woman

Timna cemetery, early 1st century CE

Calcite alabaster

LTS1992.6.180

Image 2 of 14

Head of a woman (“Miriam”)

Bit by bit the earth was cleaned away until there was revealed . . . a beautifully formed and well-preserved head of a young woman, carved in translucent alabaster.

Overwhelmed by the beauty of this piece, the Arab workmen who discovered it immediately called it the “daughter” of archaeologist Alexander Honeyman and named it Miriam. The well carved, luminous alabaster head is undoubtedly the finest funerary statue from Timna cemetery. Her large eyes are inlaid with a blue material, either lapis lazuli or blue glass. The figure’s thick, swept-back hair was made separately from plaster that is still intact, a relatively rare feature. The statue’s pierced ears once held earrings, and two holes by the side of her neck were meant for a necklace. Although no inscription identifies the young woman, “Miriam” was probably a person of means and importance.

Head of a woman (“Miriam”)

Timna, 1st century BCE–first half of 1st century CE

Alabaster, plaster, lapis lazuli or glass

S2013.2.139

Image 3 of 14

Necklace

This exceptional gold necklace confirms the advanced skill of Qataban goldsmiths. A center pendant, executed in the repoussé technique, depicts a woman’s face. The inscription—“protection of Lat, be upon Far‘iat”—identifies the original owner as a woman named Far‘iat.

Necklace

Timna, 1st century BCE–early 1st century CE

Gold

LTS2008.1.2

Image 4 of 14

Stele with the figure of a woman

Wendell Phillips noted in his book: “More important if not so aesthetically satisfying were the discoveries Professor Honeyman made that enabled him to reconstruct tentatively the ancient Qatabanian burial habits. Their tombs were elaborate and well constructed, with two to four chambers opening off an entrance corridor. Each chamber was two or three tiers deep, the tiers being separated by large paving stones built into the sides of the chamber for strong support. Within the tiered chambers Professor Honeyman found many human bones but never a complete skeleton. . . . Most of the worthwhile art objects were discovered outside the burial chambers in the entrance passages—inscribed stelae, sometimes complete pottery vessels. . . .”

Stele with the figure of a woman

Inscribed: Gabi’ of the family of Hani’mat

Timna, 3rd century BCE–mid-1st century CE

Alabaster

LTS1992.6.5

Image 5 of 14

Head of a Woman

In describing the expedition, Wendell Phillips recalled, “The objects in the graves may have been broken during looting in ancient days, shortly after the destruction of Timna and during the following centuries, although there is some doubt about this in view of the breakage everywhere, even in graves that may not have been disturbed. The looting was so extensive, especially during the Middle Ages, because of the many references, in ancient inscriptions, to gold, silver, and other valuable offerings to the gods. . . . We found no riches in the ordinary sense, but our archaeological treasures no doubt outweighed in value all the gold and silver that had been stolen from Timna in older times.”

Head of a Woman

Timna, early 1st century CE

Alabaster

LTS2011.1.3

Image 6 of 14

Stele

Cut from slabs of limestone, these funerary plaques are decorated with highly stylized faces that vary in their degree of abstraction. On the “eye stele,” the eyes, nose, and mouth are clearly visible; on others the facial features have been reduced to simple lines and curves. Faint traces of color suggest the plaques were originally painted brightly.

Stele

Timna, early 1st century CE

Limestone

LTS1992.6.41

Image 7 of 14

Stele with head of a bull

Several steles from the Haid bin Aqil cemetery near Timna are decorated with the head of a bull, a symbol of the moon god Almaqah (Ilumquh). In ancient Arabia, bulls were thought to have protective powers and carried apotropaic associations. Many of the steles also have a concave upper edge that resembles the shape of a crescent moon, a symbol repeatedly seen on ancient Arabian objects.

Stele with head of a bull

Inscribed: Thaub’il dhu-Yan’im

Timna, early 1st century CE

Alabaster

LTS2008.1.4

Image 8 of 14

Incense burner

The most common objects found in South Arabia are incense burners. Chiseled primarily out of limestone, they assume various angular shapes and sizes. The decoration usually incorporates familiar motifs, such as the auspicious symbol of an ibex, a crescent moon associated with a local god, or blind architectural windows. Hot coals placed in the cavity of the burner would have heated the incense and slowly emitted its fragrant smoke.

Incense burner

Timna, early 1st century CE

Limestone

LTS1992.6.12

Image 9 of 14

Fragment of a frieze carved with ibex heads

Similar to the figure of a bull, the ibex was believed to ward off evil. It was also associated with the rites of the sacred hunt and was sacrificed in honor of a deity, which in turn guaranteed the well-being of the community. Images of these ibexes were frequently stylized into decorative motifs, such as the row of heads on this fragmentary architectural frieze.

Fragment of a frieze carved with ibex heads

Timna, first half of 1st century BCE

Alabaster

LTS1992.6.254

Image 10 of 14

Plaque with inscription and phiale

This unique object combines a dedicatory plaque with an outstretched hand holding a flat dish, or phiale, that originally served as an oil lamp. It was found in the House Hadath, a two-story private residence with its plaster walls and floor still intact.

The inscription reads:

Hamat’amm Dharhan of the tribe of Dharhan offered to his god and lord, the master of Yaghil, a hand which is illuminated with an oil lamp and a dedication, conforming to that which is promised and assured him. He committed to the master of Yaghil his faculties, his powers, and his offerings against anyone who changes its place. By Amm, Anbay, dhat-Himyam, and with the master of Salban.

Plaque with inscription and phiale

Timna, first half of 1st century BCE

Bronze

LTS1992.6.49

Image 11 of 14

Pair of lions with riders

A private residence discovered northwest of Timna’s South Gate became known as House Yafash. When Albright excavated the house, three of its rooms were still intact. He found a variety of utilitarian objects, including a burned comb, several containers, and a stone die, that shed light on the domestic life of the ancient Qatabans. Much to the excitement of the archaeologists and their local workers, a pair of bronze lions, each surmounted by a young boy, was also unearthed at the site. As Phillips remembered, “I could scarcely see Salim because of something he held in his arms, something that looked like a green lion with a creature riding on its back.”

Covered with a layer of ash from the fire that destroyed the city of Timna in the first century CE, the two bronze lions and their boyish riders were the most important discovery made by the expedition. The sophisticated modeling and treatment of the sculptures attest to the advanced bronze casting tradition in Arabia as well as to the familiarity of local artists with the technical and artistic language of the Greeks. The iconography of the pair might relate to the cult of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, who was also a popular figure in ancient Arabia.

The lions and their riders were cast separately using the lost wax technique. Each one rests on a base with an inscription that reads, “Thuwayb and Aqrab dhu-Muhasni placed [these figures] at Yafash. Thuwayb and Aqrab of the Muhasni family decorated the house called Yafash.” The lions and their inscriptions play a critical role in establishing a chronology for the Qataban civilization and fixing its apogee in the first century CE.

Pair of lions with riders

Timna, 75 BCE–50 CE

Bronze

LTS1992.6.87 and LTS1992.6.88

Image 12 of 14

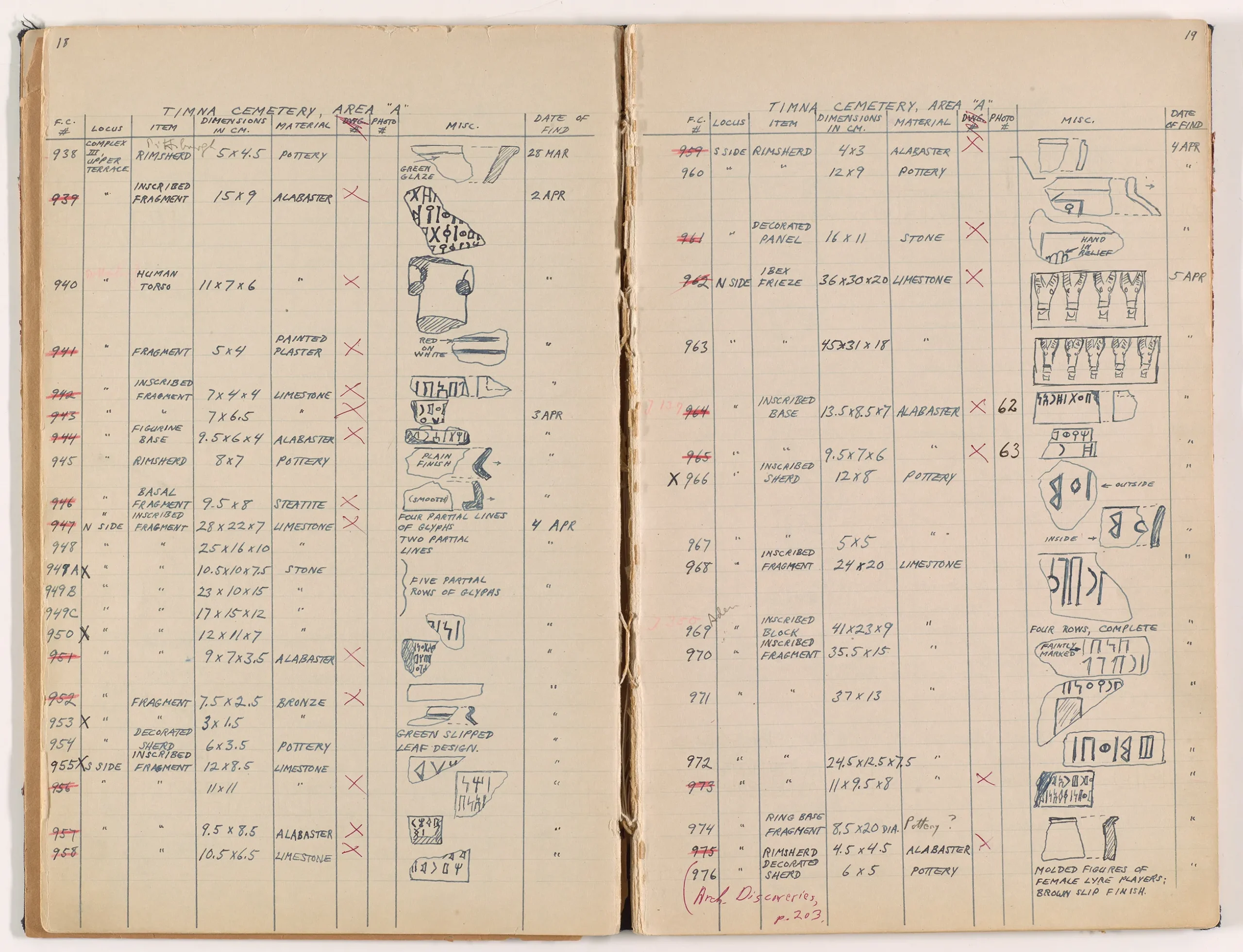

R.L. Shalkop

Members of the expedition team kept meticulous records of their finds, filling notebooks with descriptions and drawings of objects unearthed in the cemetery and at the South Gate of Timna.

Timna Cemetery, List of Objects, 2nd season, 1951

Ink entries in manufactured bound ledger with ruled paper

ELS2014.8.12

Image 13 of 14

Finds in Timna cemetery

Phillips and his team kept written records and photographs to document their finds.

Image 14 of 14

Language and Writing

The profusion of funerary, religious, and administrative inscriptions discovered in Timna and Wadi Beihan suggests the Qatabans were a highly literate culture. Scholars have classified the script as South Arabian. It contains twenty-nine letters and occurs in both a monumental and a cursive form. The absence of vowels has hampered modern understanding of the system of vocalization. Originally, the script could be written from right to left or from left to right, and at times the progression of letters switched direction in the middle of long passages. Later on, however, the preferred direction was from right to left. The script was current until the advent of Islam in the seventh century and was occasionally used to write Arabic, but it was soon abandoned in favor of the Arabic script. South Arabian still survives, however, in Ethiopian syllabary, a set of written characters that represents syllables.

Father Albert Jamme was a leading scholar in reading and recording the South Arabian script. Much of his work was done by painstakingly transcribing thousands of inscriptions. He and his workmen also made squeezes, a process whereby inscriptions carved into walls are covered with sheets of moist paper or latex to make a three-dimensional impression of the texts, as seen above.

Ancient Incense Trade

I looked back over my shoulder three thousand years and saw long trains of camels burdened with frankincense and myrrh and sometimes with gold, pearls, ivory, cinnamon, silks, tortoise shell, and lapis lazuli.

The term incense, including both frankincense and myrrh, broadly refers to a substance that emits a fragrant aroma when burned. The resins are collected from certain tree barks found only in the arid regions of southern Arabia and from a lesser variety in eastern Africa. As early as the eighth century BCE, incense was popular across the ancient world for sanctifying religious ceremonies to masking the stench of sewage. As Phillips pointed out, “Today we can scarcely appreciate the role of incense in the ancient world because, for one thing, it is difficult to imagine the odors of that world, requiring clouds of sweet-smelling smoke to cover them.”

Caravans transported incense and other luxury commodities from the southern regions of the Arabian Peninsula up the coast of the Red Sea and across the Sinai desert to Egypt. There, the precious goods were loaded on ships and sailed to destinations across the Mediterranean Sea. Arabia not only cultivated incense but also controlled its trade, making the region immensely prosperous. Timna and other cities along the principal trade roads provided necessary shelter to travelers and in return levied taxes on the incense caravans. Long-distance trade with the Greeks, Romans, and Persians also introduced new artistic and cultural traditions to ancient Arabia.

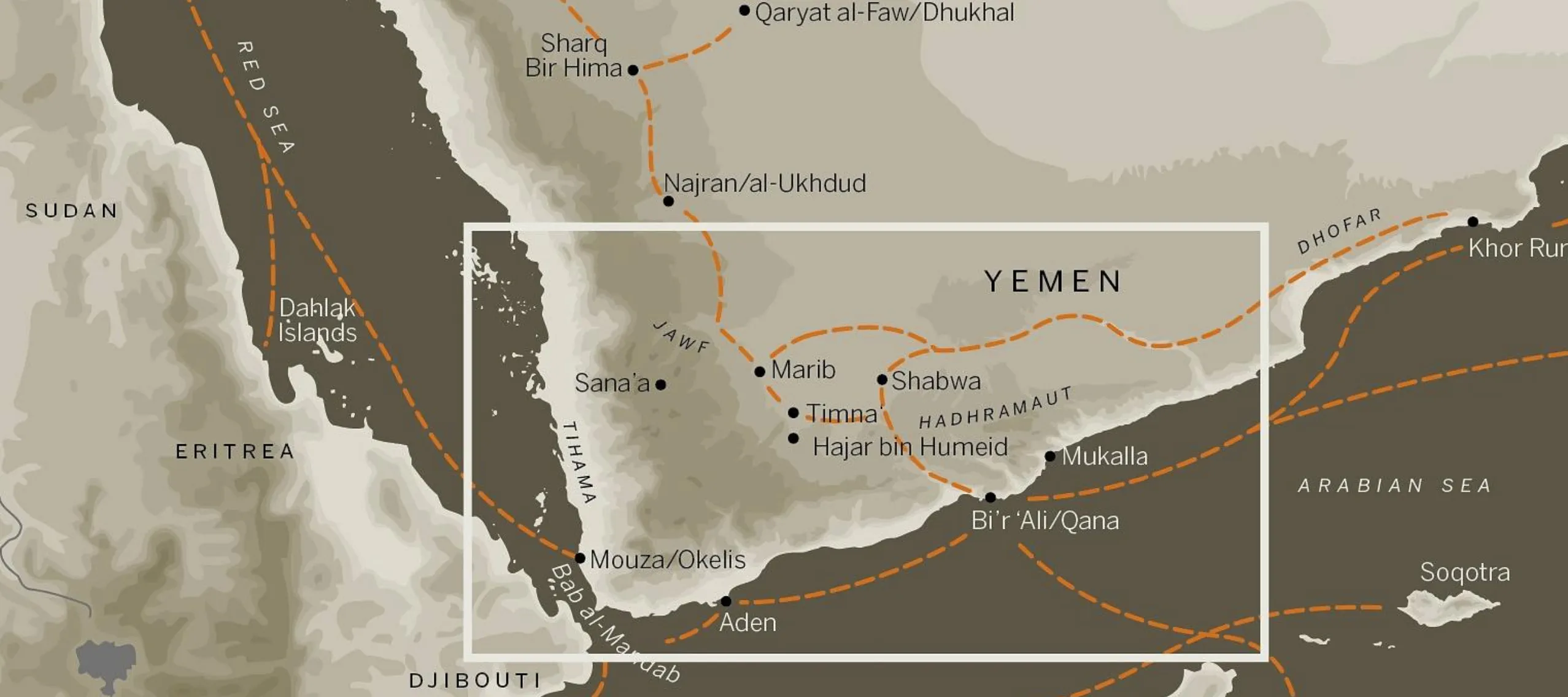

Explore this map to see the ancient incense routes. The lucrative trade in incense, in particular the highly prized commodities of frankincense and myrrh, encouraged the creation of this complex network of routes. The area in the rectangle is the focus of Unearthing Arabia.

Why Southern Arabia?

Why was I so determined to dig somewhere in South Arabia? For one thing, it was almost virgin territory. It had beckoned scholars and scientists for generations, but sand, drought, and native bullets had kept most of them away.… [Yemen] was rich with the spoils of time, and I wanted to unearth some of those riches, digging down through sand and centuries of a glorious past.

When Wendell Phillips first went on a reconnaissance trip to Yemen in 1949, few other archaeologists had ventured into the territory, where “time fell asleep.… and the husks of ancient civilizations were buried in the deep sand, preserved like flowers between the leaves of a book.” The Ottoman Turks had governed northern Yemen for centuries. Since 1832 British authorities had controlled the southern regions by establishing the so-called Aden Protectorate as a strategic point between England and its colonies in India. The Ottomans lost control of the north after World War I, and by 1950 the region was ruled by Imam Ahmed. Phillips was assured that working within the Aden Protectorate in the south safeguarded him from the political and tribal unrest in the north—an assessment that proved accurate. When Phillips and his team moved north to Marib to excavate the Awam Temple in 1951, the expedition was cut short by tribal unrest and unease at the presence of a foreign archaeological expedition. Fearing for their lives, the team hastily fled south across the protectorate’s border.

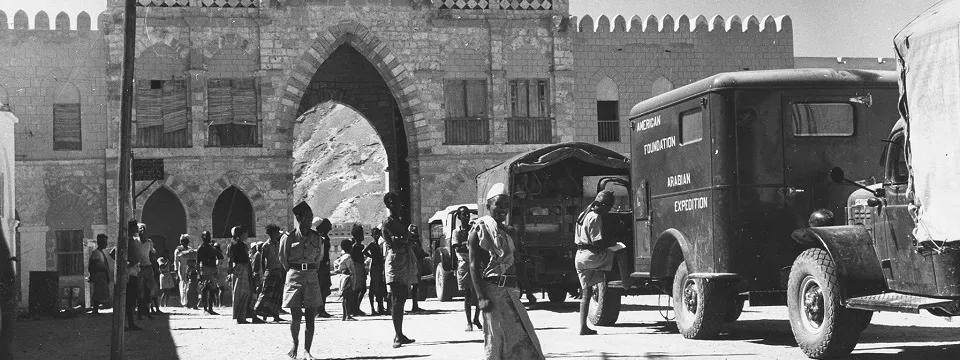

On the Road

AFSM trucks prepare to depart Mukalla for the long drive through the Hadhramaut to Timna.

Image 1 of 3

On the Road

AFSM trucks lined up for departure from Mukalla.

Image 2 of 3

Southern Arabia in 1951

As part of his expedition, Phillips shot extensive footage of southern Arabia, its people and places, and his excavations. This still is from his film Qataban and Sheba, which documents his discoveries and adventures in modern-day Yemen.

Image 3 of 3

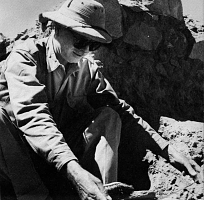

Wendell Phillips

Expedition leader

(1922–1975)

Wendell Phillips graduated from the University of California with a degree in paleontology in 1943. At the age of twenty-seven, he participated in his first expedition to Africa and Egypt. Two years later he led his own expedition to southern Arabia. He also founded the American Foundation for the Study of Man (AFSM) in 1949 with the mission to “conduct scientific research, study and investigate man and his habitats with emphasis on archaeological investigation, excavation, preservation, analysis and dissemination of scientific results.”

In 1950 and 1951, Phillips and his team excavated the site of Timna in the Wadi Beihan, where they unearthed one of the largest temples in the region, several important residences, and the Timna cemetery. The discovery of a wealth of inscriptions at Timna established a solid basis for South Arabian paleography, and the pottery finds from different occupational levels at Hajar bin Humeid allowed the creation of a chronology for the region.

In the spring of 1951 Phillips and his team moved to Marib in Yemen to fulfill his dream of excavating the Awam Temple, associated with the Queen of Sheba. Local tribal hostilities, however, prevented the team from completing the season. Under the guidance of Phillips’s sister, Merilyn Phillips Hodgson, the American Foundation for the Study of Man resumed work at Marib from 1998 until 2006.

Expedition Team

William Foxwell Albright

William Foxwell Albright

Chief archaeologist

(1891–1971)

When approached to join Phillips’s expedition, William F. Albright was perhaps the country’s most distinguished scholar of the ancient Near East. A professor of Semitic languages, Albright had produced major studies on biblical Hebrew, Aramaic, Phoenician, Assyrian, Egyptian, and Ugaritic. In the 1930s he developed a system for dating ceramics by examining the sequence of excavated strata. According to Phillips, “Expeditions come and expeditions go, potsherds are found or they remain in the ground, but there is only one Professor Albright and there will never be another.”

Gus Van Beek

Gus Van Beek

Archaeologist

(1922–2012)

A native of Tulsa, Oklahoma, Gus Van Beek excavated Hajar bin Humeid and established the first chronology for ancient South Arabian ceramics, a major contribution to the field. He studied ancient Near Eastern archaeology at Johns Hopkins University under Albright. In 1959 Van Beek joined the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History and was responsible for a major exhibition devoted to the Dead Sea Scrolls. As a result of his work in southern Arabia and at subsequent sites, Van Beek also became a leading authority in ancient and contemporary mud architecture around the world.

Alexander M. Honeyman

Alexander M. Honeyman

Archaeologist and epigrapher

(1907–1988)

Professor of Hebrew and Oriental languages at the University of St. Andrews, Alexander Honeyman supervised the first season excavation at Timna cemetery in 1950. He also was the bookkeeper and distributed weekly wages to the local workers. A meticulous excavator, Honeyman discovered the gold necklace belonging to Fari’at and the fine alabaster head that the workers referred to as Honeyman’s daughter and nicknamed “Miriam.” His discoveries at Timna allowed him to revise his understanding of Qataban tombs and burial practices. Phillips noted, “He began his investigations of certain selected tombs… determined to explore each one more thoroughly rather than do a more cursory job on the whole cemetery.”

Father Albert Jamme

Father Albert Jamme

Epigraphist

(1916–2004)

“With hardly a moment’s rest,” Phillips recalled, “Dr. Jamme was back at work on his beloved inscriptions.” An expert in ancient Semitic languages, Father Albert Jamme of the Society of Missionaries of Africa became a leading researcher in reading, interpreting, and classifying ancient South Arabian inscriptions. His first major field experience was as chief epigrapher at Timna, where he copied thousands of inscriptions. In 1952 he published some three hundred inscriptions from the Timna cemetery alone. Two years later, in 1954, he joined Catholic University in Washington, D.C., where he taught for decades. His archives are kept there today.

Gladys Terry

Gladys Terry

Business manager and driver

Gladys Terry and her husband Bill, the expedition’s field director and photographer, first joined Phillips on his 1947–49 expedition to Africa. She showed her superior mechanical capability by driving a two-ton truck and trailer from Cairo to Capetown. Terry became the first American woman explorer to reach Beihan and Hadhramaut, where her “pace-setting was so expert that not a truck blew a tire or broke a spring on that rocky road,” a practically impossible feat. She also maintained the field accounts of three major expeditions.

Eileen Salama

Eileen Salama

Arab speaker and secretary

Only nineteen years old, Eileen Salama served as translator and expedition secretary. Born in Cairo, she grew up speaking English, French, Syrian, Italian, and of course Arabic. Phillips credited her “for the tremendous good will she created for our expeditions wherever she went” and for “her major role in obtaining hitherto unobtainable information first hand from leading sultans, princes, saiyids, sheikhs, and sheriffs of South Arabia….”

Family Guide

Download and print this family guide for exploring the exhibition with children. Best for ages 6 and up.

Keep Exploring

-

Age Old Cities: A Virtual Journey from Palmyra to Mosul

January 25, 2020–October 25, 2020

-

Fashioning an Empire: Safavid Textiles from the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

December 18, 2021–May 15, 2022

- Jump To...