October 22, 2016–February 20, 2017

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

Arts of the Islamic World

In recognition of one of the world’s extraordinary collections of Qur’ans, the Freer|Sackler is hosting a landmark exhibition, the first of its kind in the United States. Some fifty of the most sumptuous manuscripts from Herat to Istanbul will be featured in The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, opening this fall. Celebrated for their superb calligraphy and lavish illumination, these manuscripts—which range in date from the early eighth to the seventeenth century—are critical to the history of the arts of the book. They were once the prized possessions of Ottoman sultans and the ruling elite, who donated their Qur’ans to various institutions to express their personal piety and secure political power. Each manuscript tells a unique story, which will be explored in this once-in-a-lifetime exhibition.

The Qur’an

As the Word of God for Muslims, the Qur’an is first and foremost an oral tradition. It was revealed in Arabic to the Prophet Muhammad through the Archangel Gabriel from about 610 until the Prophet’s death in 632. The Qur’an embodies the totality of the Revelation, and it has not changed to this day.

Several important characteristics distinguish the Qur’an from other monotheistic scriptures. For one, the text does not represent a sequential coherent whole but consists of 114 independent chapters (suras). These units are generally arranged according to length, with the longer chapters at the beginning and the shorter ones at the end of the text. Rather than offering overarching narratives, the Qur’an combines stories, teachings, and warnings. These messages are repeated intermittently throughout the text, each time from a slightly different perspective, as a way to amplify and reinforce the underlying message.A unique characteristic of the Qur’an is its self-referential nature. With God at its center, the Divine Message explicates its truthfulness, purity, and role in guiding humankind. While regarded as an oral revelation, the Qur’an also persistently presents itself as a book (kitab), emphasizing its dual nature. It also self-consciously defines its position in relation to earlier Abrahamic traditions as the final Revelation and as “a Scripture making things clear” (sura 5:15).

The Qur’an unequivocally acknowledges a single, omnipotent God. He is the creator and sustainer of the world and the one who offers guidance to men and women through the Revelation.

Heir to God’s earlier messengers, Muhammad continued the Abrahamic tradition and is considered the last and the “seal” of the prophets. Through its message, the Qur’an stresses some of the central doctrines of Islam, such as trust in the one, all-knowing God, the centrality of the Divine Message for Muslims, the role of the prophets as guides to moral and ethical conduct, and the inevitability of Judgment Day.

In addition to these core articles of belief (iman), the Qur’an offers certain guidelines, ranging from inheritance laws to daily rituals and dietary restrictions, that help establish a community of believers (umma).

-

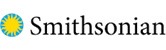

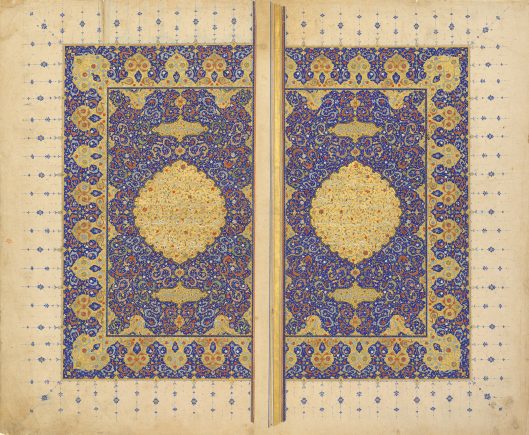

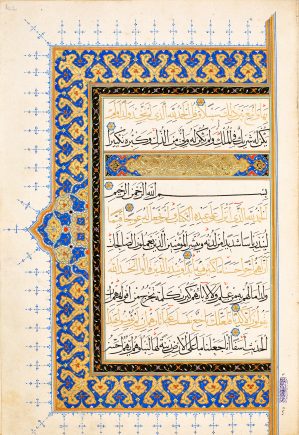

Single-volume Qur’an

Copied by Khan Ahmad Sayri

Iran, Shiraz, Safavid period, dated June 1599 (AH Dhu’l-hijja 1007)

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Transferred from the shrine of Eyüp Sultan to the Museum on October 10, 1922

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 531 -

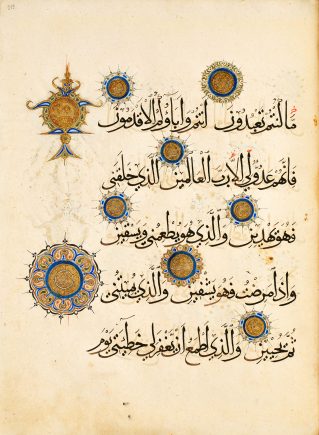

Single-volume Qur’an

Egypt, Cairo, Mamluk period, ca. 1380

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Transferred from the Kasımpaşa Piyale Pasha Mosque to the Museum on December 25, 1913

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 445 -

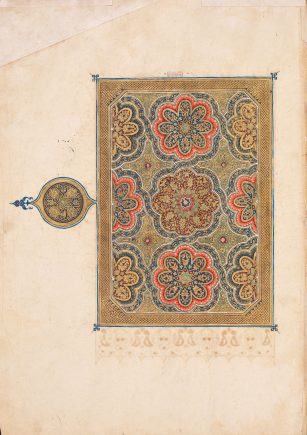

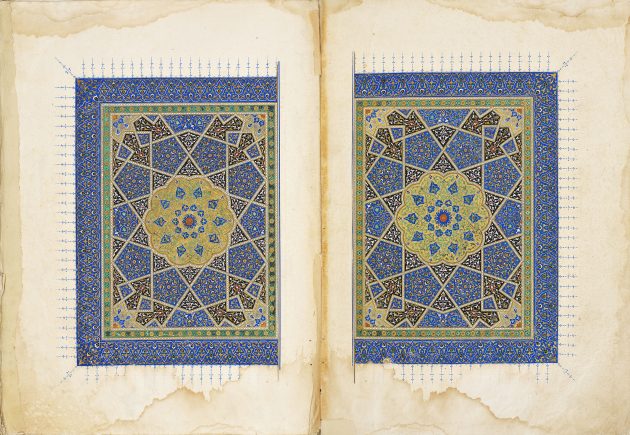

Frontispiece of a single-volume Qur’an

Historic Iran, present-day Afghanistan, Herat, Safavid period, January 1576 (AH Shawwal 983)

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Transferred from the Çarşamba Mehmed Ağa Mosque to the Museum on January 1, 1914

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 211 -

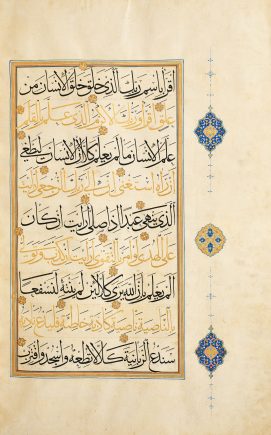

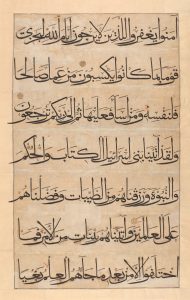

Fragment of a Qur’an

Near East, Abbasid period, 9th century

Ink, color, and gold on parchment

Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment

Freer Gallery of Art, F1937.6 -

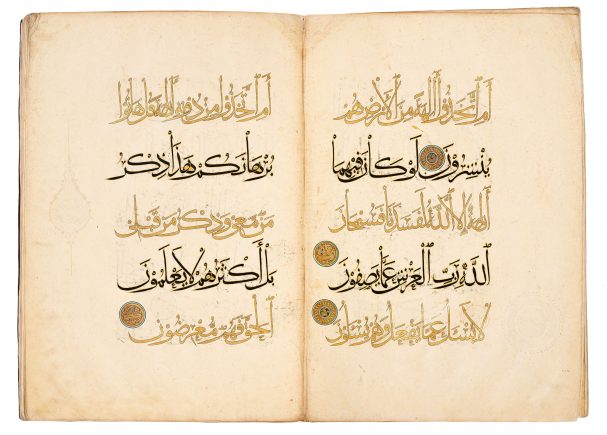

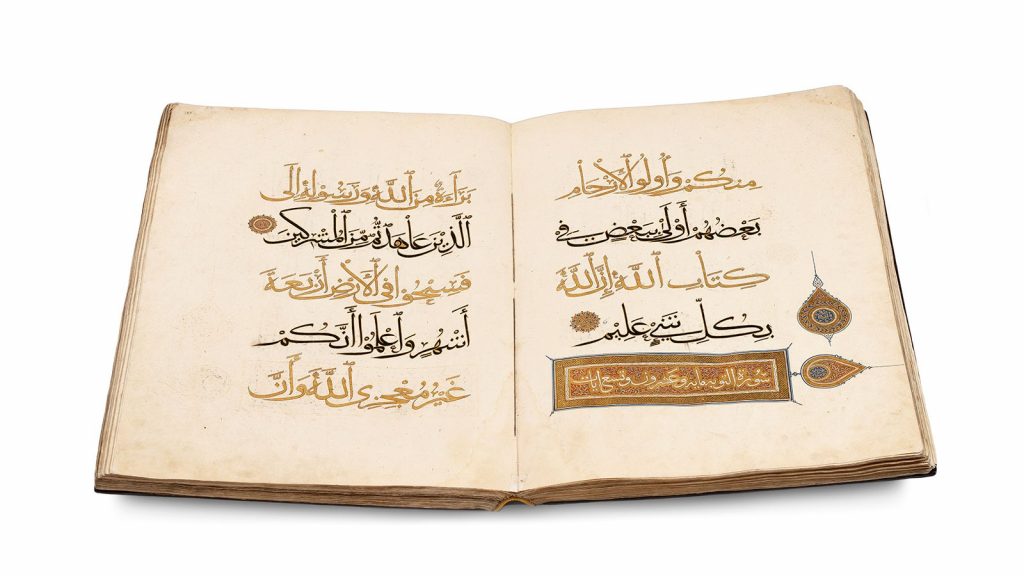

Single-volume Qur’an

Copied by al-Husayn ibn Muhammad al-Husayni

Possibly Iraq, Mosul, Il-Khanid period, August 1303 (AH Dhu’l-hijja 702)

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Lent by Mr. and Mrs. Farhad Ebrahimi, LTS 1999.3

Overview

The Art of the Qur’an, the first major exhibition on Islam’s holy text in the United States, tells the story of a group of extraordinary works. Many of these manuscripts are kept in Istanbul in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts (Türk ve İslam Eserleri Müzesi), home to one of the most outstanding collections of Qur’ans in the world. Ranging in date from the late seventh century to the early seventeenth century, most of the volumes have never been shown outside of Turkey.

The term Qur’an is derived from the verb qara’a, Arabic for “recitation” or “reading (aloud),” which underlines its fundamental nature as an oral tradition. According to Muslim belief, the Prophet Muhammad received the Word of God through the Archangel Gabriel beginning in the year 610. The successive revelations were both memorized and transcribed during Muhammad’s lifetime. Within a few decades of his death in 632, the Prophet’s followers fully transformed the Qur’an from orally transmitted words into a fixed written text.

Scribes and copyists were then faced with the challenge of lending visual form to the meaning and content of the Word of God. The result was the birth and subsequent development of Arabic calligraphy—beautiful writing. As Islam discourages figural imagery within a religious context, variations of abstract, geometric, and vegetal designs became the main form of decoration.

In the following centuries, Ottoman sultans, queens, and viziers acquired numerous Qur’ans through purchase, gift, or war booty. They endowed these cherished works to public and religious institutions to express personal piety and power and to secure prestige. Most importantly, their gesture ensured the continuous dissemination of the Qur’an’s divine blessings (baraka) among believers.

Chapter and Verse

According to Islamic tradition, the Qur’an was preserved in the Prophet’s heart and committed to memory by his closest followers. As the Revelations were not fully recorded during Muhammad’s lifetime (circa 570–632), his successors (caliph, khalifa) feared the Divine Message would be lost or corrupted. Many of the Prophet’s companions were growing old or had died in battle, and Islam was spreading beyond the Arabian Peninsula.

It was under Uthman ibn Affan (died 655), the third caliph and the Prophet’s son-in-law, that the authoritative version of the Qur’an was eventually compiled and copies were sent to major regional centers. This version became the model for all subsequent copies of the Qur’an.

Uthman’s authoritative text marks a critical moment in the history of Islam. Its arrangement is still the only one in use today. Roughly 6,240 verses (ayat) are organized into 114 chapters (suras) of descending length. Most of the longer chapters, which were revealed in Medina, appear at the beginning of the Qur’an, while the shorter ones from Mecca are toward the end. The text’s careful divisions and structure have helped believers to read, recite, and memorize the Sacred Text of Islam over the centuries.

-

Folio from a Qur’an

Attributed to Omar Aqta‘

Historic Iran, present-day Uzbekistan, probably Samarqand, Timurid period, ca. 1400

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Lent by the Art and History Collection, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, LTS1995.2.16.1 -

Two sections from a Qur’an

Near East, Umayyad period, before 750

Ink and color on parchment; binding: wood and leather

Transferred from the Damascus Umayyad Mosque to Topkapı Palace in 1911 and to the Museum in 1913

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, ŞE 80 -

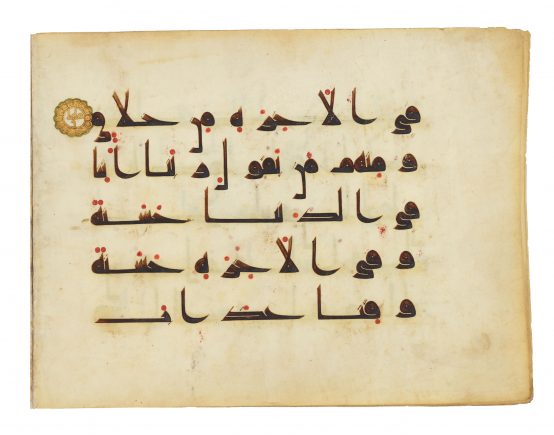

Qur’an folios

Qur’an folios

Near East, Abbasid period, late 9th–early 10th century

Ink, gold, and color on parchment

Transferred from the Damascus Umayyad Mosque to Topkapı Palace in 1911 and to the Museum in 1913

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, ŞE 611 -

Second volume of a three-part Qur’an

Copied, illuminated, and bound by Mahmud ibn Ramadan

Probably Turkey, Konya, Seljuq period, ca. 1280

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Transferred from the tomb of Ala’ al-Din Kay Qubad I in Konya to the Museum in 1917

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 438 -

Section of a Qur’an

Iran, probably Shiraz, Timurid period, ca. 1430–40

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Transferred from the mosque of Sultan Ahmed I to the Museum on April 4, 1914

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 564

Ink and Gold

While Caliph Uthman is credited with compiling and disseminating the authoritative version of the Qur’an, Ali ibn Abi Talib, the fourth caliph (died 661), is considered the first calligrapher and illuminator. Furthermore, Ali, who was also the cousin and a son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad, is identified as the inventor of angular kufic, the first formal script for copying Qur’anic manuscripts.

By the eleventh century, kufic was replaced by six rounded cursive styles that became known as al-aqlam al-sitta (The Six Pens). The art of embellishing and illuminating the Qur’an also dates to at least the eighth century. Since images in the Qur’an are believed to distract worshipers from God, illuminators over the centuries developed a repertoire of non-figurative motifs to mark text divisions and to heighten the beauty of the Divine Message.

Chroniclers in sixteenth-century Iran, Turkey, and India discuss the development of calligraphy by tracing the lineage of its leading practitioners. Starting with Ali ibn Abi Talib, they list masters and students as well as describe their contributions to the tradition as it spread throughout the Islamic world. Works by many of these luminaries are seen in this section.

-

Single-volume Qur’an

Attributed to Abdallah al-Sayrafi

Iran, probably Tabriz, Il-Khanid period, ca. 1330

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Transferred from the Çoban Mustafa Pasha Mosque in Gebze to the Museum on October 12, 1913

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 487 -

Single-volume Qur’an

Iran, Timurid period, ca. 1440

Color and gold on colored paper

Transferred from the Nuruosmaniye Library to the Museum on June 14, 1916

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 41 -

Double page from a Qur’an

Attributed to Ruzbihan Muhammad al-Tab’i al-Shirazi

Iran, Shiraz, mid-16th century

Ink, gold, and color on paper

Purchase—Smithsonian Unrestricted Trust Funds, Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, and Dr. Arthur M. Sackler

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, S1986.82.1–2 -

Sections of a thirty-part Qur’an

Copied by Ali al-Husayni

Iraq, Mosul, Il-Khanid period, November 1310 (AH Rajab 710)

Gold, color, and ink on paper

Transferred from the mosque of Rüstem Pasha to the Museum on January 13, 1914

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 540 -

Qur’an cover

Historical Iran, present-day Afghanistan, Safavid period, probably Herat, ca. 1580

Leather, polychrome pigments and gold

Transferred from the mosque of Sultan Ahmed I to the Museum in 1914

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 2665

Power and Prestige

As the physical manifestation of the Word of God, Qur’an manuscripts (mushaf in Arabic) are thought to carry a special aura. Believers can receive baraka, “God’s blessing,” whether they see or touch a Qur’an, hear the recitation of its verses, or read from one. Certain copies are considered particularly charged, such as those associated with Uthman, Ali, and other important figures of early Islam. Others are deemed special because they are connected to the holy sites of Mecca and the Prophet’s mosque in Medina. In some instances, the lineage of a manuscript, be it copied by a celebrated calligrapher or commissioned by an important and devout figure, enhanced the prestige of a Qur’anic volume.

Centuries after their completion in Isfahan, Baghdad, Shiraz, or Herat, many of the finest Qur’ans entered Ottoman collections. They were acquired by sultans, queens, and viziers through purchase, gift, or as war booty. Some were kept in private libraries or royal treasuries; others were offered to secure political and military alliances, and still others were awarded in return for loyalty and support. Qur’ans were also frequently endowed (waqf in Arabic) to public institutions as an expression of the devotion and generosity of donors. Whether used for teaching, recitation, or public display, these volumes ensured the continuous dissemination of God’s blessings. Ottoman royal women in particular donated Qur’ans to the many religious and charitable institutions they built and supported. Such noble deeds allowed them to play an active role in Ottoman social and religious life.

Imperial women played an important role in Ottoman cultural, political, and religious life notably after 1541, when Sultan Süleyman I authorized them to move from the old palace into the Topkapı royal residence. Spouses, concubines, and mothers of the imperial children—especially those who bore the eldest son of the reigning sultan—wielded considerable power.

These women also received substantial incomes. Visible expressions of their wealth and authority in Ottoman society were the numerous charitable and religious institutions they founded and supported, including mosques, schools, public kitchens, hospitals, and bathhouses. In addition, the royal women often endowed precious copies of the Qur’an to their own foundations and others associated with family members. This tradition continued until the end of the Ottoman Empire in the early twentieth century.

-

Sections of a thirty-part Qur’an

Probably copied by Ahmad ibn al-Shaykh al-Suhrawardi al-Bakri

Illuminated by Muhammad ibn Aybak ibn Abdallah

Iraq, Baghdad, Il-Khanid period, 1307–8 (AH 707)

Gold, color, and ink on paper

Transferred from the mausoleum of Shehzade Mehmed to the Museum on January 1, 1914

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 538 -

Single-volume Qur’an

Copied by Shams al-Baysunghuri

Historic Iran, present-day Afghanistan, Herat, Timurid period, 1434 (AH 837)

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Transferred from the library of the Hagia Sophia to the Museum on April 13, 1914

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 294 -

Single-volume Qur’an

Probably Turkey, Edirne, 1457–58 (AH 862)

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Transferred from the library of the Hagia Sophia to the Museum in 1914

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 30 -

Single-volume Qur’an

Copied by Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Khalili al-Tabrizi

Iran, Safavid period, 1554–55 (AH 962)

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Transferred from the tomb of Hatice Turhan Sultan to the Museum on January 3, 1914

Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, TIEM 423

Lapis and Gold

Completed in September 1517, this luxurious manuscript is a triumph of illumination and calligraphy that showcases the skill of artists at the Ottoman court. At the time, the Ottoman dynasty ruled a vast territory, stretching from Egypt to Iraq, with its capital in Istanbul. Signed by both its calligrapher and illuminator—a relatively rare practice—the manuscript probably was meant for the Ottoman ruler Sultan Selim I (reigned 1512–20), perhaps to celebrate his conquest of Mamluk Egypt and Syria in 1517. Almost seventy years later, his great-granddaughter Ismihan (died 1585) dedicated the volume to the mausoleum of her father, Sultan Selim II (reigned 1566–74), and instructed that it should be recited over her father’s tomb for the eternal salvation of his soul.

Manuscripts on the Move

Muslims hold copies of the Qur’an in the highest esteem, as they consider the text to be the Word of God revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. Since the late seventh century, the text of the Qur’an has been carefully transcribed and decorated, first on parchment and later on paper. Many manuscripts became prized possessions of wealthy and educated elites throughout the Islamic world.

Decades or even centuries after copies of the Qur’an were created in cities such as Herat, Baghdad, and Cairo, Ottoman sultans, queens, and viziers acquired some of the most precious ones. These volumes were treasured in private libraries and given as gifts and rewards. Most frequently, they were donated to religious institutions to be read, recited and studied. Inscriptions, notes, and repairs provide snapshots of the manuscripts’ histories—including their long-distance travels before the early twentieth century, when they finally settled in Istanbul’s Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts.

Wondrous Words

An extraordinary feat of calligraphy, this Qur’an represents a seldom-seen level of artistic perfection. Two of the period’s best-known artists, Ahmad al-Suhrawardi and Muhammad ibn Aybak, transcribed and illuminated the manuscript. The Mongol ruler Uljaytu (reigned 1304–16), a descendent of Genghis Khan, commissioned it for his monumental tomb in Sultaniyya, in northwestern Iran. After his death, reciters prayed for Uljaytu’s eternal salvation by reading the text over his tomb.

Dividing the Qur’an into thirty equal sections (in Arabic, juz,plural: ajza’) helped worshippers read the entire text over the course of a month, a practice that was especially popular during Ramadan.

The Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts

One of the most renowned cultural institutions in the region, the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts (Türk ve İslam Eserleri Müzesi) plays an integral role in the rich cultural history of Istanbul. It opened to the public in 1914 as the Museum of Islamic Endowments (Evkaf-ı İslamiye Müzesi) in the soup kitchen of the Süleymaniye Mosque complex. The collection consisted of treasures that the Ottomans had endowed to religious institutions throughout the empire since at least the 1500s. When the unity of the empire was threatened, the government transferred these works to Istanbul for safekeeping. With the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, the institution changed its name to the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts.

The collection was moved in 1983 to its current location—the imposing palace of the grand vizier Ibrahim Pasha (died 1536). Overlooking the Byzantine Hippodrome and now the “Blue Mosque,” the building was probably a wedding gift when the grand vizier married Sultan Süleyman’s sister, Hatice Sultan. In the twentieth century, it was used as military barracks and fell into disrepair. After two decades of extensive restoration, the former palace reopened in 1983 as the new location of the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts.

Today the collection contains some of the earliest and finest carpets from the Islamic world and over 17,000 manuscripts, including more than 3,000 Qur’ans and 250,000 early Qur’anic fragments from the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, among other treasures.

Past Events

(All events concluded)

Symposium: The Word Illuminated: Form and Function of Qur’anic Manuscripts

Thursday–Saturday, December 1–3, 2016

Turkish Embassy and Ripley Center Lecture Hall

Watch online

Costly paper, finely tooled bindings, special scripts, and intricate illumination are among the characteristics that distinguish the manuscripts in The Art of the Qur’an. In this symposium, investigate the materiality of luxury copies of the Qur’an made between the eighth and the seventeenth century from Herat to Istanbul. Also learn about the complex and layered significance these Qur’ans acquired as they changed ownership. Speakers examine the volumes in their historical, cultural, and artistic contexts and discuss their use as potent symbols of piety and political and religious authority. The symposium is organized in conjunction with the exhibition The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts and is made possible in part through the support of the El-Hibri Foundation.

Saturday, October 22, 2016

Watch online

How does one become a master calligrapher today? Join Mohamed Zakariya, one of the world’s foremost calligraphers, and student calligrapher Aisha Imam as they discuss their professional paths and training. Born in the United States, Zakariya earned diplomas from the Research Centre for Islamic History, Art, and Culture in Istanbul. His work has been collected and displayed worldwide and featured in documentaries. He also designed Eid holiday stamps for the US Postal Service. Imam has a background in international health and development, using arts as a means of awareness. Her deep appreciation of traditional Islamic art has been fostered by a diverse set of teachers of classical Islam, as well as by her travels abroad.

Saturday, October 22, 2016

Watch Elinor Aishah Holland as she demonstrates the basics of Arabic calligraphy. Holland introduces tools and materials used in calligraphy, as well as basic techniques. Holland’s passion for calligraphy was sparked by a visit to Istanbul as a teenager. She has studied with the master calligrapher Mohamed Zakariya for many years and received her diploma in 2013. Holland teaches, presents, and exhibits throughout the United States and Canada.

Saturday, October 22, 2016

Take a melodious journey from the heartland of Arabia to Istanbul with musicians Roshni Samlal and Kane Mathis. Tracing the journey of the Qur’anic text, Samlal and Mathis introduce musical instruments and traditions from across the Islamic world. Mathis holds a diploma from the Tiramang Traditional Music School in Gambia. He also studied at Istanbul Technical University Conservatory as an apprentice to oud virtuoso Münir Beken. Samlal is a tabla player who hails from the West Indies. Her vocalist father, Mukund Samlal, initiated her into the tradition of Indian classical music.

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

Join exhibition curator Massumeh Farhad as she looks at the religious, historical, and artistic importance of the exceptional manuscripts preserved by powerful sultans, queens, and viziers. In The Art of the Qur’an, she discusses how calligraphers and illuminators transformed a series of orally transmitted revelations into the Qur’an’s fixed text, which has remained unchanged over the centuries.

Session A: Thursdays, October 27, November 3, 10, and 17, 2016

Session B: Saturdays, October 29, November 5, 12, 19, 2016

In this four-week course, learn techniques used to create the spectacular works in The Art of the Qur’an. Examine historic Qur’an manuscripts in the galleries, and then delve into bookmaking materials and techniques with accomplished calligrapher Khalid Casado and artist Josh Berer. During the four sessions, participants gain a deeper understanding of Arabic calligraphy and the fascinating history of book arts by practicing basic calligraphy, paper dyeing and marbling, illumination, and simple bookbinding. For adults and students ages 16 and up.

Tuesday, November 15, 2016

Join exhibition curator Simon Rettig as he explores the production of sumptuous Qur’an manuscripts whose origins span a millennium and from Egypt to Afghanistan. In The Art of the Qur’an, Rettig also presents the staggering journeys these copies experienced from the time of their creation to their final destination in Istanbul.

Sunday, November 20, 2016

Watch online

Can understanding the Torah, the Bible, and the Qur’an increase empathy and connections among cultures that are often at odds? Join a conversation with local faith leaders on the similarities and differences among prophetic traditions in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The stories of Noah, Abraham, Jonah, Mary, and others play a key role in all three religions. Their stories are told differently, and the lessons for the faithful are not always the same, yet all three faiths see themselves as following the tradition of Abraham. In this interfaith dialogue, an imam, a minister, and a rabbi share the teachings they take from these ancient tales.

Panel members include Imam Talib Shareef, Rabbi Jack Moline, and Reverend Donald Isaac.

Made possible in part through the support of the El-Hibri Foundation.

Sunday, February 19

Watch online

Did you know that Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, owned a translation of the Qur’an? That the first Muslims in the DC area arrived as enslaved Africans in the early 1700s? Or that Washington’s first mosque, the Masjid Muhammad, played an important part in the civil rights movement? Join us for a conversation about the fascinating history of Muslim communities in Washington, DC, in connection with the exhibition The Art of the Qur’an.

Panelists include:

James H. Johnston, an attorney and journalist, has published extensively on Washington, DC, history. His works include the book From Slave Ship to Harvard: Yarrow Mamout and the History of an African American Family.

Amir Muhammad is director and curator of America’s Islamic Heritage Museum, located on Martin Luther King Junior Avenue in DC’s Anacostia neighborhood. His numerous publications include Muslims in America: Seven Centuries of History (1312–1998).

Asma Naeem is an associate curator of prints, drawings, and media arts at the National Portrait Gallery. A specialist in American and contemporary Islamic art, she is particularly interested in the effects of displacement, the history of technology, and the sensorial imagination of both artist and beholder.

Moderator:

Shadi Hamid is a senior fellow in the Project on US Relations with the Islamic World in the Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution. His most recent book is Islamic Exceptionalism: How the Struggle over Islam is Reshaping the World.

Open Studio: Dazzling Designs of the Qur’an

Saturday, October 22, 2016

Saturday, January 14, 2017

Discover The Art of the Qur’an with free family activities. In this Open Studio, we explore illuminated designs in manuscripts of the Qur’an. Take a family-friendly tour (12:30 and 2:30 pm) of the exhibition, and then head to the ImaginAsia classroom to get creative. Tea and refreshments provided. All ages welcome with adult companions.

Family Workshop: The Art of Illumination in the Qur’an

Sunday, November 6, 2016

Saturday, December 17, 2016

Saturday, January 7, 2017

Sunday, January 8, 2017

Visit the exhibition The Art of the Qur’an with teaching artist Lubna Zahid and learn about the beautiful patterns in the Qur’an. Then, return to the classroom to collaborate with family and friends on illuminating a bookmark inspired by the exhibition. This program is designed for children ages 6–12 and adults to enjoy together.

Educator Resources

How can you bring The Art of the Qur’an: Treasures from the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts into your classroom? Educators of many disciplines and grade levels can use this exhibition as a teaching and learning opportunity. Utilize the resources below to deepen your understanding of the role of Islam and the Qur’an in history and art.

Islam and Religious Art | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Read about the key tenets of Islam, important historical figures and events, and the role of art in the religion’s history and practice.

Islamic Art and Culture | National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Consult this in-depth teaching resource to learn about the history of Islam and the variety of objects created by artists of the Islamic world.

Traces of the Calligrapher | Asia Society, New York City

Learn about Islamic calligraphers’ tools, training, and techniques.

Art Spots | Bridging Cultures Bookshelf: Muslim Journeys

Explore these visual essays on different aspects of Islamic art—from calligraphy to architecture.

Art of the Islamic World | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Find answers to common questions that arise when teaching about Islam and Islamic culture.

How to Look at a Qur’an: Educator Resource (PDF, 6MB)

Lesson Plan: Mosque Lamps (PDF, 77KB)

Grade levels: fourth grade and up

In this activity, students will incorporate patterns and calligraphy to create structures resembling mosque lamps. Students also will learn about the Islamic world’s significant role in the development of trade and its resulting wealth.

Explore and Discover

Lapis and Gold

Completed in September 1517, this manuscript is a triumph of illumination and calligraphy that showcases the skill of artists at the Ottoman court. Explore the manuscript by flipping through the pages and clicking on hotspots to learn more. These folios contain the last fourteen chapters of the Qur’an.

Wondrous Words

An extraordinary feat of calligraphy, this Qur’an represents a seldom-seen level of artistic perfection as two of the period’s best-known artists, Ahmad al-Suhrawardi and Muhammad ibn Aybak, transcribed and illuminated the manuscript. Explore the manuscript by flipping through the pages and clicking on hotspots to learn more. These folios contain verses 25 to 52 of sura 21, al-Anbiya’ (The Prophets), contained within juz 17.

Activities for Kids and Families

Manuscripts on the Move

Decades or even centuries after copies of the Qur’an were created in cities such as Herat, Baghdad, and Cairo, Ottoman sultans, queens, and viziers acquired some of the most precious ones. These volumes were treasured in private libraries and given as gifts and rewards. Most frequently, they were donated to religious institutions to be read, recited and studied. Inscriptions, notes, and repairs provide snapshots of the manuscripts’ histories—including their long-distance travels before the early twentieth century, when they finally settled in Istanbul’s Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts. Use this interactive feature to trace their journeys.

For Kids

Discover the arts of the Islamic world through an extraordinary group of manuscripts of the Qur’an, the central holy text in Islam. Explore featured artworks spanning nine hundred years and from Afghanistan to Turkey through fun facts, discussion questions, and art-making activities. Experiment with creating elegant calligraphy, a colorful lamp, a working loom, and your own illuminated design.

What is it made of? Ink, color, and gold on parchment

When was it made? Ninth to tenth century

Where was it made? North Africa or the Near East

Discover

Unlike paper that is made from rags and fibers in the Islamic world, this page was created from animal skin! Known as “parchment,” this long-lasting material took a long time to prepare. A parchment-maker would first remove all the hairs and clean and dried the animal skin. The next step would be to stretch out the skin before preparing it for writing.

For a books with lots of pages, one would have needed the skins of many animals, often a whole herd of sheep, as many as five hundred or six hundred. Such requirements meant that manuscripts on parchment were very expensive. Not surprisingly, only the most important texts were written on animal skin, and only the richest people were able to afford them.

The text is written in Arabic, the language of the Qur’an, which we read from right to left. It describes duties for Muslims, how to be kind, compassionate, and respectful to others and take responsibility for ones’ behavior. The script with its square letters is one of the first to be developed for copying the Qur’an. You may notice red dots next to the letters. They were added to help readers pronounce certain sounds.

Imagine

The person who wrote this text, known as a “calligrapher,” shortened some of the letters and words and lengthened others. Why would someone do this? The calligrapher wanted to suggest a neat, rectangular border for the script without actually drawing one. Today, this practice is called “justifying” the text. You can find justified text in modern books.

Create

Find a rectangular shape, and then trace it onto a piece of paper. Write a sentence or two inside the rectangle you drew about the types of duties you have in your family. Like the calligrapher, try to write in a straight line while fitting your words within the shape. You may have to vary the space between letters to shorten and extend some words. It might be more difficult than you might think!

What is it made of? Enameled and gilded glass

When was it made? Around 1360

Where was it made? Egypt

Discover

More than seven hundred years ago—long before light bulbs—this colorful glass lamp, along with many others, hung from the ceiling of an Egyptian mosque, a place of worship for Muslims. The beautiful writing on the neck compares God to the light in a lamp.

Between sections of writing, three round medallions identify the person who ordered this lamp to be made. His name was Sultan Hasan, a powerful ruler of Egypt who built many mosques and other buildings and ordered lamps to light the structures.

A glass maker made this lamp by blowing and shaping liquid glass in a furnace. After it cooled, he decorated it with a paint-like substance called “enamel.” To make the color stick, the artist then attached the glass to a metal rod called a “pontil” and inserted the lamp back into the furnace. Watch artisans make hand blown glass in a video to better visualize this process.

Imagine

This lamp hung near many others just like it, making the mosque glow and sparkle. Look up at the ceiling of the room you are in and imagine dozens of these lamps dangling above you, flickering with light. Share out loud how that would change the feeling of the space around you.

Create

Ready, set, glow! Make a lamp from recycled objects. Decorate the outside of a glass jar with tissue paper, paint, and glue to make a colorful candleholder, or use a hammer and nails (with an adult’s help) to poke a pattern of holes in a plastic bottle. Drop a battery-powered light inside to see it shine!

What is it made of? Ink, color, and gold on paper

When was it made? 1598

Where was it made? Iran

Discover

Take a moment to look closely at this beautiful page’s complex designs. What shapes do you see? Name as many as you can.

Now, look at the border and find a shape that resembles a star with eight points. If you were to cut the shape in two, each half would look exactly like the other. This is called “symmetry.” There are many examples of symmetry in nature. Next time you take a walk outside, count how many examples of symmetry you find.

More than four hundred years ago, a calligrapher named Khan Ahmad Sayri copied this Qur’an. We know very little about him besides that he lived and worked in Shiraz, a city in southern Iran. Sayri probably worked in a workshop with many other calligraphers, all specialists in beautiful writing. His manuscripts were popular in neighboring Turkey, and powerful and wealthy people in both Iran and Turkey collected them.

Imagine

Admire all of the subtle varieties of color on this page. The detailed pattern has three different shades of gold, ranging from a dull, greenish one to a brilliant yellow one. Other colors—deep and light blues and reds—animate the page as well. How many colors can you find?

Create

Find shapes in this page that the artist repeated to create complicated patterns. Cut your own interesting shape from cardboard. On a piece of paper, place the cardboard in lots of different positions, tracing around it each time to make a kaleidoscope-like design. Fill in your design using similar shades of color.

What is it made of? Silk-satin, lampas weave

When was it made? Seventeenth to eighteenth century

Where was it made? Turkey

Discover

This noticeable red and white cloth would have covered a coffin-shaped structure, marking the burial place of an important person. Woven in silk with a distinct zigzag design, the beautiful white are in Arabic, a language written from right to left. The largest bands include the two main beliefs for Muslims: “There is only one God, and Muhammad is his Prophet.” The rest of the writing is made up of verses from the Qur’an.

Ottoman weavers were celebrated all over the Islamic world and Europe for their beautiful silk fabrics. Like this example, the silks were usually woven in bright colors with bold designs. Silks were used for clothing and for furnishings, such as cushions, curtains, and covers.

Imagine

A lot of work went into making this luxurious large tomb cover. The artist probably drew the design on a piece of paper before creating the textile. This involved interlacing two sets of silk yarns on a loom, a machine for making fabric.

Create

Make your own loom! Find a rectangular piece of cardboard, and then follow the instructions with help from an adult.

Suras 45:9–13, 45:13–16

What is it made of? Ink, color, and gold on paper

When was it made? Around 1400

Where was it made? Historic Iran, present-day Uzbekistan

Discover

These two pages belong to the largest and one of the most impressive Qur’ans ever produced! Their original borders have been lost, but each page must have measured about 5.5 x 3.25 feet.

We think these pages were created for the founder of the Timurid dynasty, known as Timur or Tamerlane, who lived more than six hundred years ago. He established one of the largest and most powerful dynasties of the Islamic world. Timur ordered his craftsmen to construct large buildings, many of which have since collapsed because they had to be built quickly. He also liked big objects and manuscripts, such as this Qur’an.

These pages may be part of a Qur’an written by a calligrapher known as Omar Aqta‘. The story goes that he copied a Qur’an that was so small, it fit into a ring. Timur was unimpressed by the work. So, Omar Aqta‘ made a new copy so large that it had to be carried by a wheelbarrow! This time, Timur was extremely pleased and showered Omar Aqta‘ with praise and royal favors.

Imagine

Creating these huge sheets of paper must have been a difficult job. The papermaker may have used a ladle to scoop smaller pieces of the wet paper into floating molds that stuck together. Another possibility is that he made paper strips that he then pasted together. To this day, no one knows for sure.

Create

Write a letter or postcard about a time when you had a difficult task to overcome. Think back to Omar Atqa‘ and his challenge for inspiration. What choice did you make to get through the challenge? What was the outcome? Share your story with your friends and family.

Join the countless artists who have been inspired by the art of the Qur’an by creating your own colorful design. Download the template and print out a blank pattern—or better yet, head to the exhibition to find one in the galleries! Once you’re done illuminating the page, share a picture of your work on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram with #artofquran.

Reviews & Press

It’s a glorious show, utterly, and like nothing I’ve ever seen…

…some of the most beautiful and significant calligraphy and book illustration ever produced.

The dazzling array of calligraphic variety across these manuscripts is astounding.

…some of the finest existing examples from diverse historical eras and cultures,…

A magic visual experience

The Quran copies are like little peepholes, allowing us to peer back into the lives of people we never knew.

…the loan of these items from Turkey is in the finest tradition of illuminated Qur’ans.

Number three exhibition to see in 2016 –Best Art of the Year,

Additional support is provided by Hagop Kevorkian Fund, El-Hibri Foundation, Capital One, and an anonymous donor.

Detail, Single-volume Qur’an; Attributed to Abdallah al-Sayrafi; Iran, probably Tabriz, Il-Khanid period, ca. 1330; Ink, color, and gold on paper; Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Istanbul, TIEM 487

- Jump To...