October 24, 2015–January 31, 2016

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

Japanese Art

Discover Tawaraya Sōtatsu, one of the most influential yet elusive figures in the history of Japanese visual culture. Sōtatsu: Making Waves is the first exhibition outside Japan to tell his story—a once-in-a lifetime experience in which two of the artist’s most important paintings, the Freer’s Waves at Matsushima and Dragons and Clouds, will be on public view.

video | "Sōtatsu: Making Waves" | View on YouTube

About

Tawaraya Sōtatsu (ca. 1570‒ca. 1640), a fountainhead of Japanese painting and design, is one of the most influential yet elusive figures in Japanese culture. Sōtatsu’s work is instantly recognized by its bold, abstracted style, lavish swaths of gold and silver, and rich jewel tones. Much of the artist’s life, however, remains a mystery. How a working-class owner of a Kyoto fan shop transformed into a sophisticated designer with a network of aristocratic collaborators is still an enigma.

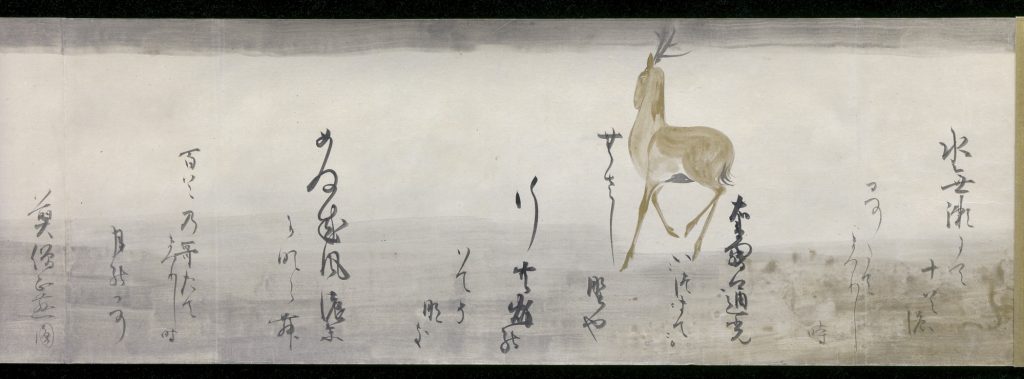

Sōtatsu: Making Waves is the first in-depth examination of this major Japanese artist. The exhibition convenes for the first time more than seventy of Sōtatsu’s masterpieces from collections in Japan, Europe, and the United States, along with homage pieces by later artists that demonstrate his long-ranging influence. Highlights include Waves at Matsushima and Dragons and Clouds, along with fans, albums, hanging scrolls, and paintings. The Freer|Sackler is the only venue for this first major Sōtatsu retrospective in the Western Hemisphere.

Museum founder Charles Lang Freer, a prescient late nineteenth-century collector who amassed several of Sōtatsu’s most noted paintings, is widely credited with introducing both Sōtatsu and his frequent collaborator Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637) to Western audiences. Due to restrictions in Freer’s will, the works cannot travel outside the Freer and Sackler Galleries, making this exhibition a watershed moment in our understanding of Sōtatsu.

The Importance of Sōtatsu

In early seventeenth-century Kyoto, Sōtatsu, a talented craftsman, found himself at the center of a momentous shift in Japanese society. When the ancient royal court ceded its power to rising classes of warriors and merchants, a new audience emerged, eager to bedeck itself with the trappings of the cultural elite. Sōtatsu, through his experimental painting techniques and brilliantly conceived compositions, transformed and translated Japan’s tightly controlled courtly artistic style for this new age.

His revolutionary designs, and the works created by later followers, coalesced into the style known as rinpa, a triumph of Japanese aesthetics that emerged in the early seventeenth century and continued into the early twentieth century. Despite being named for the Edo-period painter Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716), rinpa (translated as “school of Rin”) owes much of its legacy to Sōtatsu and Kōetsu. In fact, it was Sōtatsu who advanced the vitally important painting technique known as tarashikomi (“dropping in”), in which paint is dropped into a still-wet background to create delicate, serendipitous details such as flower petals and water ripples.

Sōtatsu’s influence cannot be overstated. By the late nineteenth century, rinpa was firmly established as a major movement and, to some extent, became synonymous in the West with Japanese culture. The first modern Sōtatsu exhibition in Tokyo in 1913 galvanized the art world, inspiring a new generation of Japanese artists. His designs echo within the works of luminaries such as Klimt and Matisse—and throughout Art Deco style—making his four hundred-year-old paintings appear unexpectedly contemporary.

Japan’s cultural leaders have declared 2015 as the 400th anniversary of the beginning of the rinpa style, commemorating the shogun’s gift of land in 1615 that formed Kōetsu’s Kyoto artist colony. This exhibition, made possible through a partnership among international scholars and lenders, will complement rinpa displays throughout Japanese museums.

Symposia

video | Sōtatsu in Washington: Insights, Discoveries, and Reflections | View on YouTube

Sōtatsu in Washington: Insights, Discoveries, and Reflections

Freer, Meyer Auditorium

Saturday, October 24, 10 am-5 pm

Program:

- Julian Raby, Welcome Remarks

- James T. Ulak, Introductory Remarks: Why Sōtatsu? Why Here?

- Yukio Lippit, Sōtatsu: Five Perspectives

- Okudaira Shunroku, Keeping Score: The Memory of Sōtatsu’s Vision

- Nakamachi Keiko Charles Lang, Miraculous Waters: Expression and Meaning in the Waves at Matsushima

- James T. Ulak, Freer and the “Discovery” of Kōetsu and Sōtatsu

- Furuta Ryō, Sōtatsu in the 20th Century

Sōtatsu’s Times: Perspectives on the Culture and Politics of Kyoto

Freer, Meyer Auditorium

Saturday, December 5, 10 am-5 pm

Program:

- 10–10:30 am: Coffee in the Freer Conference Room

- 10:30–10:45 am: Welcome

- Yukio Lippit, Harvard University

- James Ulak, Freer|Sackler

- 10:45 am–1:00 pm: Presentations

- Mary Elizabeth Berry, University of California, Berkeley, “It Was the Best of Times to Be an Artist”

- Morgan Pitelka, Carolina Asia Center and University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, “The Arts of Reinvention: Kyoto Culture in the Early Seventeenth Century”

- Jacqueline I. Stone, Princeton University, “Sōtatsu, Kōetsu, and the Lotus Sūtra: The Religious World of the Kyoto Townspeople”

- 1:00–2:30 pm: Lunch break

- 2:30–4:00 pm: Presentations

- Tomoko Sakomura, Swarthmore College, “Sōtatsu and the Art of Mix and Match”

- Joshua S. Mostow, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, “Sōtatsu and Tales of Ise (Ise monogatari)”

- 4 pm: Round table discussion

- 5 pm: Program concludes

Sōtatsu’s Times: Perspectives on the Culture and Politics of Kyoto

Freer, Meyer Auditorium

Saturday, December 5, 10 am-5 pm

It Was the Best of Times to Be an Artist

Mary Elizabeth Berry, University of California, Berkeley

Extraordinary wealth and unsurpassed building projects propelled art production to industrial levels during Sōtatsu’s day. Competition and collaboration among artists and their patrons inspired both technical and stylistic invention in every art form—painting, calligraphy, printing, textiles, ceramics, lacquer, metalwork, drama, poetry, music, and more. This lecture situates Sōtatsu in a social context of unprecedented mobility and discovery, as makers of a new peacetime world were transforming not just the arts but mining and mathematics, cookery and crop selection, and more.

The Arts of Reinvention: Kyoto Culture in the Early Seventeenth Century

Morgan Pitelka, Carolina Asia Center and University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

With the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate in Edo in 1603, the elites of Kyoto found themselves in an unfamiliar position: marginalized from the center of politics for the first time in two and a half centuries. The city’s artists and patrons responded with a collaborative zeal that embraced the patterns of the past to remake the fabric of the present. In the products and practices of Sen Sôtan, Hon’ami Kōetsu, and Kobori Enshû, among others, the city reinvented itself as the center of a vibrant new culture that drew on Chinese, imperial, samurai, and urban commoner precedents.

Sōtatsu, Kōetsu, and the Lotus Sūtra: The Religious World of the Kyoto Townspeople

Jacqueline I. Stone, Princeton University

Kyoto’s thriving mercantile culture supported notable artistic innovations, such as the works of Tawaraya Sōtatsu and his frequent collaborator Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637). Like a majority of the Kyoto townspeople (machishū), Kōetsu, and likely Sōtatsu, belonged to the Nichiren school of Buddhism. This school had been founded by the medieval teacher Nichiren (1222–1282) and was based on the Lotus Sūtra, celebrated for its message that all living beings can become buddhas. This talk explores connections between machishū artistic production and faith in the Lotus Sūtra, which is particularly well documented in the case of Kōetsu and his enclave of Nichiren Buddhist devotees. Later known as “Kōetsu village,” this community of artists and craftsmen aimed both to foster creative endeavor and to embody Nichiren’s ethos of “realizing the buddha land in this present world.” It flourished for more than two decades.

Sōtatsu and the Art of Mix and Match

Tomoko Sakomura, Swarthmore College

Tawaraya Sōtatsu is recognized for his inspired curation of images and compositions drawn from a wide array of sources, such as scenes from painted handscrolls and details of buildings. His work also features fluid play between painting formats of differing scale, such as fans and folding screens. Though Sōtatsu’s biography and training remain elusive, his work posits a painter with an enterprising attitude toward formats, conventions, and contexts of painting and calligraphy. To illustrate the visual dialogues that inform Sōtatsu’s paintings, this talk explores how the concept of “mixing and matching” shaped artifacts of the past and Sōtatsu’s present.

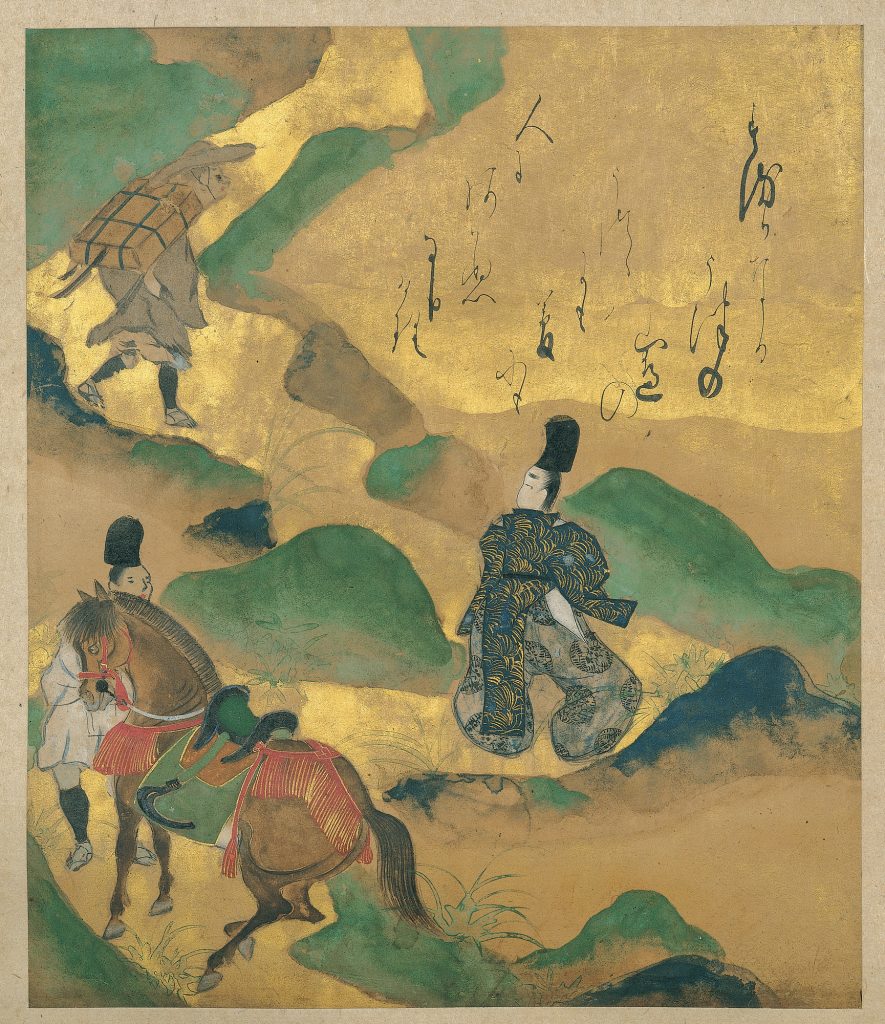

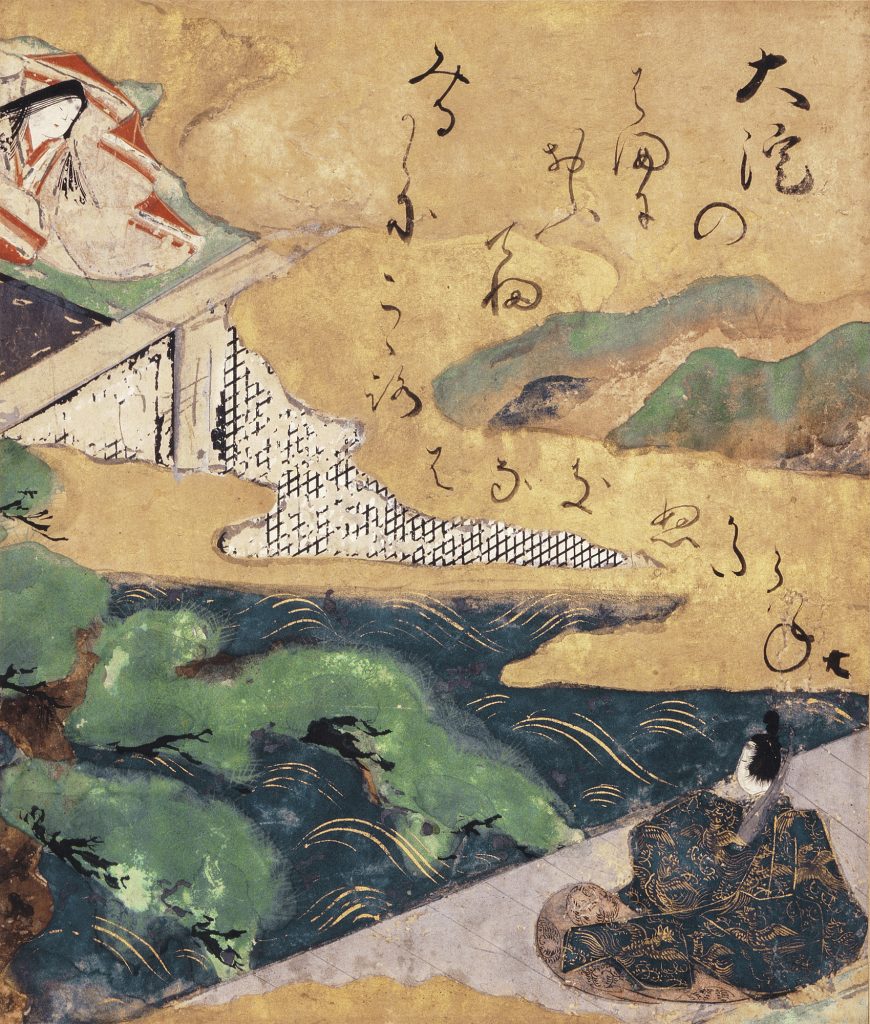

Sōtatsu and Tales of Ise (Ise monogatari)

Joshua S. Mostow, University of British Columbia, Vancouver

A tenth-century court classic, The Ise Stories (Ise monogatari) recounts the tale of Captain Ariwara no Narihira (825–880) and his romantic encounters with women throughout Japan. The 125 loosely connected episodes center on an exchange of love poems, each a demonstration of wit, sensitivity, and ideas of courtliness.This talk focuses on the unusually close relationship between Sōtatsu and The Ise Stories, exploring the sources of his imagery and the variety of media in which he produced “Ise-pictures” (Ise-e).

Sōtatsu’s Times: Perspectives on the Culture and Politics of Kyoto

Freer, Meyer Auditorium

Saturday, December 5, 10 am-5 pm

Mary Elizabeth Berry is Class of 1944 Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley. Her publications include Hideyoshi (Harvard University Press, 1982), The Culture of Civil War in Kyoto (University of California Press, 1994), and Japan in Print: Information and Nation in the Early Modern Period (California, 2006). She is now working on a book that tries to answer the following question: How did Japan make the revolutionary leap from a manorial economy to a market economy in the seventeenth century? She has served as president of the Association for Asian Studies and is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Mary Elizabeth Berry is Class of 1944 Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley. Her publications include Hideyoshi (Harvard University Press, 1982), The Culture of Civil War in Kyoto (University of California Press, 1994), and Japan in Print: Information and Nation in the Early Modern Period (California, 2006). She is now working on a book that tries to answer the following question: How did Japan make the revolutionary leap from a manorial economy to a market economy in the seventeenth century? She has served as president of the Association for Asian Studies and is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Morgan Pitelka is the director of the Carolina Asia Center and an associate professor in the Department of Asian Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he teaches premodern Japanese history. His research focuses on the history of the samurai, tea culture, and ceramics, and the methodology of material culture studies. His publications include Spectacular Accumulation: Material Culture, Tokugawa Ieyasu, and Samurai Sociability (Hawaii, 2016); What’s the Use of Art? Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context, co-editor with Jan Mrazek (Hawaii, 2007); Handmade Culture: Raku Potters, Patrons, and Tea Practitioners in Japan (Hawaii, 2005); and Japanese Tea Culture: Art, History, and Practice (Routledge, 2003).

Morgan Pitelka is the director of the Carolina Asia Center and an associate professor in the Department of Asian Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he teaches premodern Japanese history. His research focuses on the history of the samurai, tea culture, and ceramics, and the methodology of material culture studies. His publications include Spectacular Accumulation: Material Culture, Tokugawa Ieyasu, and Samurai Sociability (Hawaii, 2016); What’s the Use of Art? Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context, co-editor with Jan Mrazek (Hawaii, 2007); Handmade Culture: Raku Potters, Patrons, and Tea Practitioners in Japan (Hawaii, 2005); and Japanese Tea Culture: Art, History, and Practice (Routledge, 2003).

Jacqueline I. Stone is a professor in the Religion Department at Princeton University, where she teaches Buddhism and Japanese religions. She received her PhD from the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her major research area is premodern Japanese Buddhism. She has worked extensively on the Japanese reception of the Lotus Sūtra and the Tendai and Nichiren Buddhist traditions. Her books and co-edited volumes include Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism (University of Hawai’i Press 1999) and Readings of the Lotus Sūtra (co-edited with Stephen Teiser, Columbia University Press 2009).

Jacqueline I. Stone is a professor in the Religion Department at Princeton University, where she teaches Buddhism and Japanese religions. She received her PhD from the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her major research area is premodern Japanese Buddhism. She has worked extensively on the Japanese reception of the Lotus Sūtra and the Tendai and Nichiren Buddhist traditions. Her books and co-edited volumes include Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism (University of Hawai’i Press 1999) and Readings of the Lotus Sūtra (co-edited with Stephen Teiser, Columbia University Press 2009).

Tomoko Sakomura is associate professor of art history at Swarthmore College. She holds a PhD in art history and archaeology from Columbia University. Sakomura is a specialist in Japanese art history whose work examines the relationship between word and image in the visual culture of late medieval Japan. Her forthcoming book Poetry as Image: The Visual Culture of Waka in Sixteenth-Century Japan (Brill 2015) examines the ways the visual culture of classical Japanese poetry (waka) engaged with practice and protocol developed over the previous six centuries, and what these engagements reveal about the role of the past in cultural productions of the present.

Tomoko Sakomura is associate professor of art history at Swarthmore College. She holds a PhD in art history and archaeology from Columbia University. Sakomura is a specialist in Japanese art history whose work examines the relationship between word and image in the visual culture of late medieval Japan. Her forthcoming book Poetry as Image: The Visual Culture of Waka in Sixteenth-Century Japan (Brill 2015) examines the ways the visual culture of classical Japanese poetry (waka) engaged with practice and protocol developed over the previous six centuries, and what these engagements reveal about the role of the past in cultural productions of the present.

Joshua S. Mostow is professor of Asian studies at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. He received his doctorate in the comparative literature and literary program of the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of numerous studies on the interrelations between literary texts and images in premodern Japanese culture. His most recent bsook, Courtly Visions: The Ise Stories and the Politics of Cultural Appropriation(Brill, 2014), traces the reception and use of the tenth-century literary romance into the modern day through an examination of both visual and literary sources. He was recently elected as a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, the senior Canadian collegium of distinguished scholars, artists, and scientists.

Joshua S. Mostow is professor of Asian studies at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. He received his doctorate in the comparative literature and literary program of the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of numerous studies on the interrelations between literary texts and images in premodern Japanese culture. His most recent bsook, Courtly Visions: The Ise Stories and the Politics of Cultural Appropriation(Brill, 2014), traces the reception and use of the tenth-century literary romance into the modern day through an examination of both visual and literary sources. He was recently elected as a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, the senior Canadian collegium of distinguished scholars, artists, and scientists.

Galleries

Tawaraya Sōtatsu (active circa 1600–40) was one of the most dynamic and inventive painters in the long history of Japanese visual expression. A maker of finely decorated papers and folding fans, he worked in relative anonymity. The Tawaraya, his shop/studio in Kyoto, was well regarded, and his clients included aristocrats and merchants. Yet beginning shortly after his death (circa 1640) and through much of the Edo period (1615–1868), he vanished into obscurity, eclipsed by the reputations of calligrapher Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637) and painter Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716). Not until the early twentieth century—thanks in part to the efforts of Charles Lang Freer—did the art world recognize Sōtatsu’s consequential role.

This exhibition begins with one of Sōtatsu’s greatest achievements, Waves at Matsushima, then reveals the elements and techniques he used to produce his finest works, and finally examines the ways in which he inspired artists in the modern era.

Objects on view will rotate throughout the run of Sōtatsu: Making Waves. We hope you’ll revisit the exhibition to see all of the works. Stay tuned for more details.

Explore this exhibition

Sōtatsu in the 21st Century

High-resolution digital photography has greatly enhanced our ability to study and disseminate images of rare and fragile materials. Such images can be used for collaborative scholarly projects, conservation and scientific research, international education programs, and the sheer pleasure of close observation. The Freer and Sackler Galleries are striving to present more digital technology within the museums, and artworks by Tawaraya Sōtatsu are prime candidates for such experiments.

The Gods of Wind and Thunder

Depictions of the gods of wind and thunder circulated in Asia a millennia before they were depicted by Sōtatsu. With their respective attributes—a bag (wind) and drums (thunder)—these figural representations of natural forces were widely available in seventeenth-century Japan. Two wood sculptures from the Kamakura period (1185–1333), housed at the Sanjūsangen-dō temple complex, were likely accessible to Sōtatsu, who worked nearby. The thunder god figure also appears in narrative scrolls that describe the founding of Kitano Tenjin Shrine in northern Kyoto, which Sōtatsu may have known as well. The Gods of Wind and Thunder were revered by generations of painters, most notably Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) and Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828), who created their own versions in homage to Sōtatsu. The original paintings are now at theKyoto National Museum, just a few blocks from the Kenninji temple where they once resided.

The Gods of Wind and Thunder

Digital image printed on washi with gold leaf applied

Kenninji, Kyoto

High-resolution facsimile of The Gods of Wind and Thunder

Tawaraya Sōtatsu (act. ca. 1600–40)

Japan, 1600s

Ink, color, and gold leaf on paper

Designated National Treasure

Kyoto National Museum (long-term loan from Kenninji, Kyoto)

Image 1 of 2

The Gods of Wind and Thunder

Depictions of the gods of wind and thunder circulated in Asia a millennia before they were depicted by Sōtatsu. With their respective attributes—a bag (wind) and drums (thunder)—these figural representations of natural forces were widely available in seventeenth-century Japan. Two wood sculptures from the Kamakura period (1185–1333), housed at the Sanjūsangen-dō temple complex, were likely accessible to Sōtatsu, who worked nearby. The thunder god figure also appears in narrative scrolls that describe the founding of Kitano Tenjin Shrine in northern Kyoto, which Sōtatsu may have known as well. The Gods of Wind and Thunder were revered by generations of painters, most notably Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) and Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828), who created their own versions in homage to Sōtatsu. The original paintings are now at theKyoto National Museum, just a few blocks from the Kenninji temple where they once resided.

The Gods of Wind and Thunder

Digital image printed on washi with gold leaf applied

Kenninji, Kyoto

High-resolution facsimile of The Gods of Wind and Thunder

Tawaraya Sōtatsu (act. ca. 1600–40)

Japan, 1600s

Ink, color, and gold leaf on paper

Designated National Treasure

Kyoto National Museum (long-term loan from Kenninji, Kyoto)

Image 2 of 2

Charles Lang Freer and the “Discovery” of Sōtatsu

After much dickering of a most exasperating nature, I bought a pair of six-fold screens by Sotatsu.… [The dealer’s] original price was ten thousand dollars but I cut his prices exactly in half.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919), the founder of the Freer Gallery of Art, was without peer as a collector of Japanese art. His route to this artistic tradition emerged from his friendship with American artist James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), who inspired Freer to make five visits to Japan. Among his many acquisitions, none rival the paintings by Tawaraya Sōtatsu (active circa 1600–40). Freer perhaps first became aware of the artist through an interest in ceramics by Sōtatsu’s creative partner, Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637). That led to a fairly rapid series of purchases, culminating in two pairs of screens—Dragons and Clouds, purchased in 1905, and Waves at Matsushima, purchased in 1906. Both now rank as undisputed masterworks.

Freer purchased the Waves at Matsushima screens from Kobayashi Bunshichi (1861–1923), a Japanese dealer who was particularly attuned to the collector’s developing taste for Sōtatsu. In 1906, he persuaded Freer that he had found a masterpiece, which led to the delivery of the Matsushima screens to the American’s residence in Detroit that October. True to form as a hard bargainer, Freer halved the price requested by the dealer.

Kanzan and Jittoku

Two Chinese hermits—known in Japanese as Kanzan (Chinese: Hanshan) and Jittoku (Chinese: Shide)—lived near the sacred mountain Tiantaishan during the Tang dynasty (618–907). They appear frequently in Zen Buddhist paintings, representing rejection of the secular world and the search for enlightenment. Their disparity in education and social status is considered unimportant. Here, Kanzan opens a scroll of his poetry, watched by Jittoku, a servant at a monastery.

Gahō’s composition contrasts dark and light tones and sets the figures in a conventional but highly simplified landscape. The painting was shown in an exhibition organized by the Kangakai (Society for the Appreciation of Paintings), established by American scholar Ernest F. Fenollosa to promote new Japanese-style paintings. Gahō’s techniques provide a subtle modern sensibility, which was encouraged by Fenollosa, who wrote to Charles Lang Freer in 1902 that the painting had created such excitement that “the Emperor asked to borrow it and kept it several months.” Fenollosa’s influence in persuading Western collectors to acquire paintings by living Japanese artists may account for the fact that few of the paintings shown by the Kangakai have remained in Japan.

Kanzan and Jittoku

Hashimoto Gahō (1835–1908)

Japan, ca. 1886

Hanging scroll

Ink on paper

Freer Gallery of Art, Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1902.227

Image 1 of 3

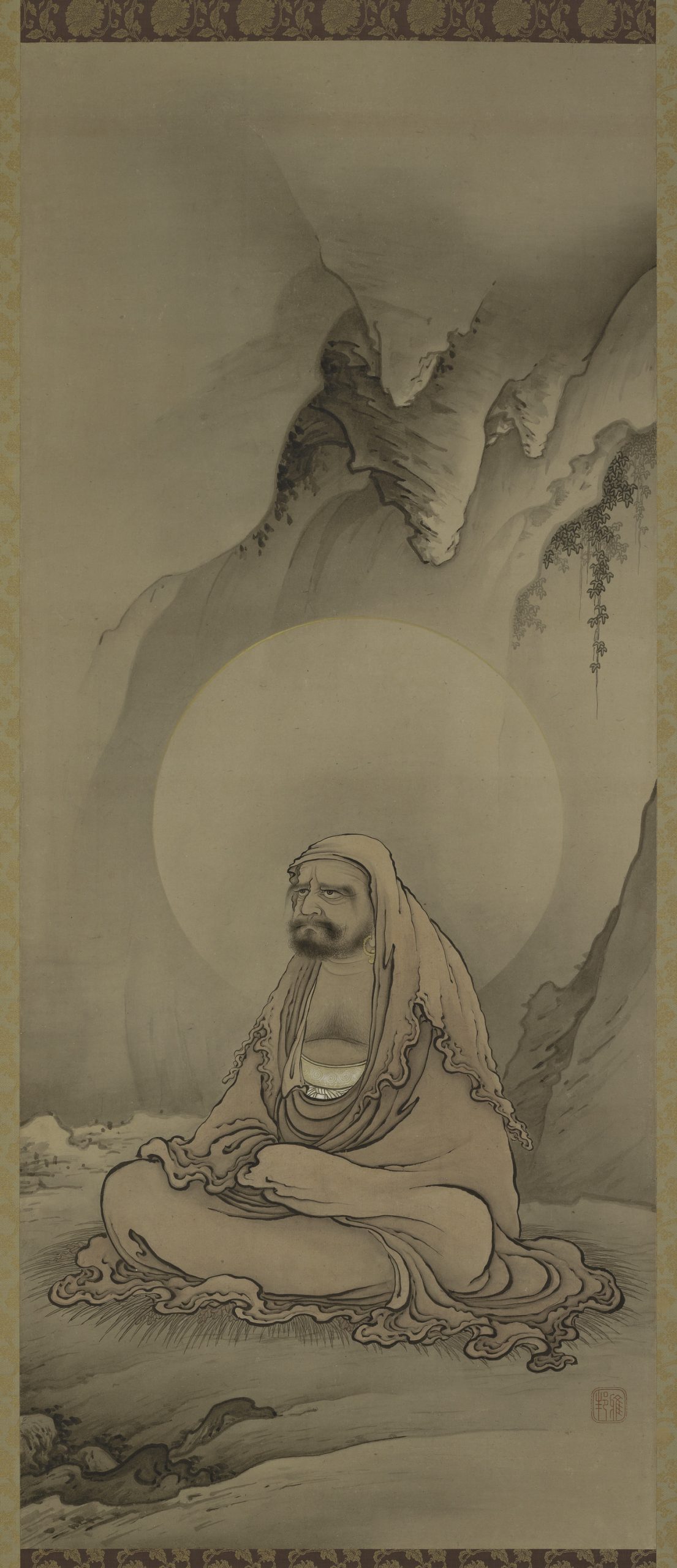

Bodhidharma Seated in Meditation

Gahō was one of several classically trained Japanese painters whose traditional client base disappeared when Japan abruptly modernized in the late nineteenth century. He benefited from the promotion, guidance, and friendship of Ernest Fenollosa, the American scholar who introduced Chinese and Japanese art to international audiences. In 1902, Charles Lang Freer purchased this painting from Fenollosa, who noted the “sweet human earnestness” of Gahō’s rendering.

Bodhidharma (Japanese: Daruma) was a South Indian prince who traveled to China and taught meditation, the fundamental practice of the Buddhist school known as Zen in Japan and Chan in Chinese. He is portrayed here with an aura of light surrounding his head, a detail typical in representations of Buddhist deities. Portraits of the founders of lineages are often given to pupils as a symbol of enlightenment. The images also serve a commemorative function on the anniversary of Bodhidharma’s death, which Japanese Zen monks observe on October 5.

Bodhidharma Seated in Meditation

Hashimoto Gahō (1835–1908)

Japan, ca. 1885

Hanging scroll

Ink and color on paper

Freer Gallery of Art, Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1902.228

Image 2 of 3

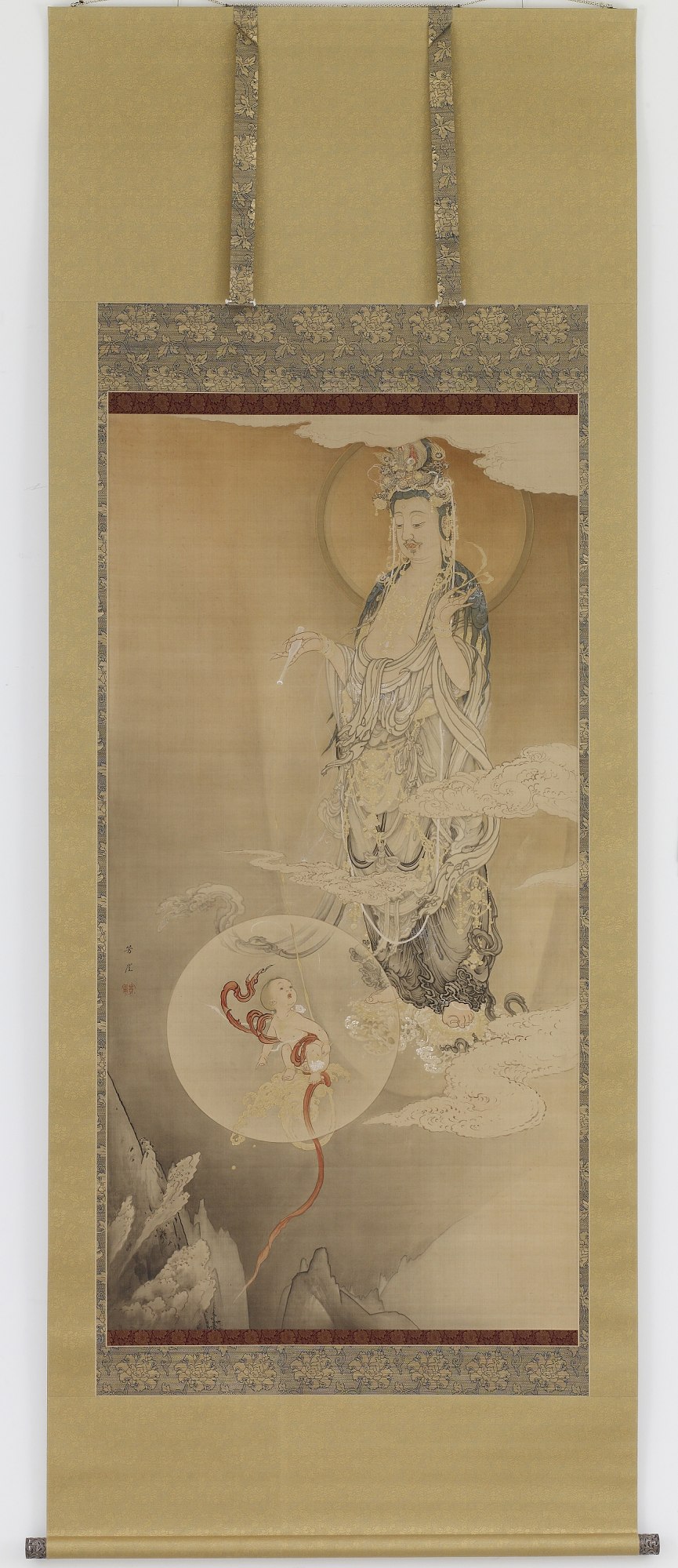

Hibo Kannon

This monumental painting of Kannon, a bodhisattva (enlightened being) associated with infinite compassion, portrays the Buddhist deity in the guise of a maternal figure who nurtures an infant enveloped by a halo. Both figures hover high above a stark landscape that represents the world where the newborn child will live.

Hōgai’s work was produced for exhibition display rather than for veneration. It was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1883 and acquired by Parisian art dealer Siegfried Bing (1838–1905). Ernest Fenollosa acquired it from Bing and in 1902 sold it to Charles Lang Freer. Fenollosa grandly titled the painting The Creation of Man, perhaps attempting to give the work a universal meaning.

Hibo Kannon

Kano Hōgai (1828–1888)

Japan, 1883

Hanging scroll

Ink, color, silver, and gold on silk

Freer Gallery of Art, Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1902.225

Image 3 of 3

Freer and Japan’s Modern Art

When Freer first visited Japan in 1895, he went as a tourist and not as a connoisseur of Asian art. But by his next visit in 1907, he was attracting the attention of Japanese dealers and collectors. Freer built his reputation as a collector of premodern works, but he also visited Japan between 1895 and 1913, when artists were defining their own identities. Some asserted a continuity with the past, others broke with it, but all were interested in creating a viable market for their work.

Two advisors encouraged Freer to support contemporary artists. Scholar Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) had urged the struggling painters of the once-powerful Kanō school to adapt their styles to appeal to international collectors. He recommended their works to Freer, who acquired a select group, including several by Kanō Hōgai (1828–1888) and Hashimoto Gahō (1835–1908). These artists depicted traditional subjects with modeling of figures, shading, perspective, and other Western techniques.

Hara Tomitaro (1868–1939) was the scion of a wealthy silk-producing family and, like Freer, a collector of premodern Chinese and Japanese art. He too helped emerging Japanese painters search for a modern visual vocabulary with international appeal, using his own collection to expose them to works by Sōtatsu and his followers. In 1915, Hara’s son Zenichirō asked whether Freer was interested in the young artists embraced by his father. Freer politely demurred. Gahō and Hōgai would represent the extent of his ventures into twentieth-century Japanese painting. Of the many choices available to Freer on the modern stage, he opted for the most conservative.

Rediscovery

Japan ended its two-hundred-year policy of national isolation in the mid-nineteenth century, and within a few decades, the Meiji government (1868–1912) had begun a rapid modernization. The long-established art world was thrown into upheaval. Previously reliable patronage declined or disappeared. Photography and multiple-image reproduction usurped the longtime tradition of woodblock printing. Buddhism lost government support and thus the ability to commission artworks. People turned away from patrimony in favor of Western styles.

Japanese arts and crafts flooded international expositions in Europe and the United States, opening Japan’s visual culture to admiration and scrutiny. The influence of Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858), and Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) on Western art is well documented. Japanese-themed fashions and objects filled American and European homes. To survive in the domestic and international markets, many Japanese artists working in the early twentieth century looked to the past for inspiration and rediscovered works by Sōtatsu and those who came after him.

In this new environment, artists sought to answer a number of questions: Could they develop a visual approach that had a Japanese identity but was understood by Westerners? Could they adapt their traditional but archaic art forms by introducing perspective and modeling techniques? Could they use Western painting styles to depict Japanese themes? Could they incorporate the powerful abstractions of the Rinpa style in their own work? In effect, their response to those questions would “transfer” Sōtatsu’s work to modern Japanese and Western art.

Waterfowl in Snow

Tsuji Kakō was born in Kyoto. At the age of nine he began to study painting under Kōno Bairei (1844–1895) one of the first great modernists. Bairei transmitted and adapted a style of lyrical realism developed in the eighteenth century by Maruyama Ōkyo (1733–1795). Kakō absorbed those lessons, but in the second decade of the twentieth century, while he was in his early fifties, he produced paintings—including Cranes of Immortality on the opposite wall—that were audaciously decorative in coloration and composition. The influence of Sōtatsu and Kōrin was clear.

Waterfowl in the Snow captures a startled flock of ducks alighting in dense, swirling snow. The scene may reference Sōtatsu’s flocks of cranes, but Kakō has added blinding snow. At first glance, his rendering of water seems to use tarashikomi, but it is actually a mixed-pigment technique unique to Kakō’s works.

Waterfowl in Snow

Tsuji Kakō (1870–1931)

Japan, ca. 1918

Hanging scroll

Ink, gofun, and colors on silk

Gift of Griffith and Patricia Way, in honor of the 75th Anniversary of the

Seattle Art Museum, 2010.41.23

Image 1 of 16

Cranes of Immortality

The most striking feature of Cranes of Immortality is Tsuji Kakō’s treatment of the water surface, where carefully blended pigments create an effect that recalls shading techniques in oil painting. Sōtatsu’s influence can be seen in the dots in the background and the gold paint that enhances the breaking waves. Look for another work by this artist, Waterfowl in Snow, on the opposite wall.

Cranes of Immortality

Tsuji Kakō (1870–1931)

Japan, ca. 1918

Hanging scroll

Color on silk

Gift of Griffith and Patricia Way, in honor of the 75th Anniversary of the

Seattle Art Museum, 2010.41.80

Image 2 of 16

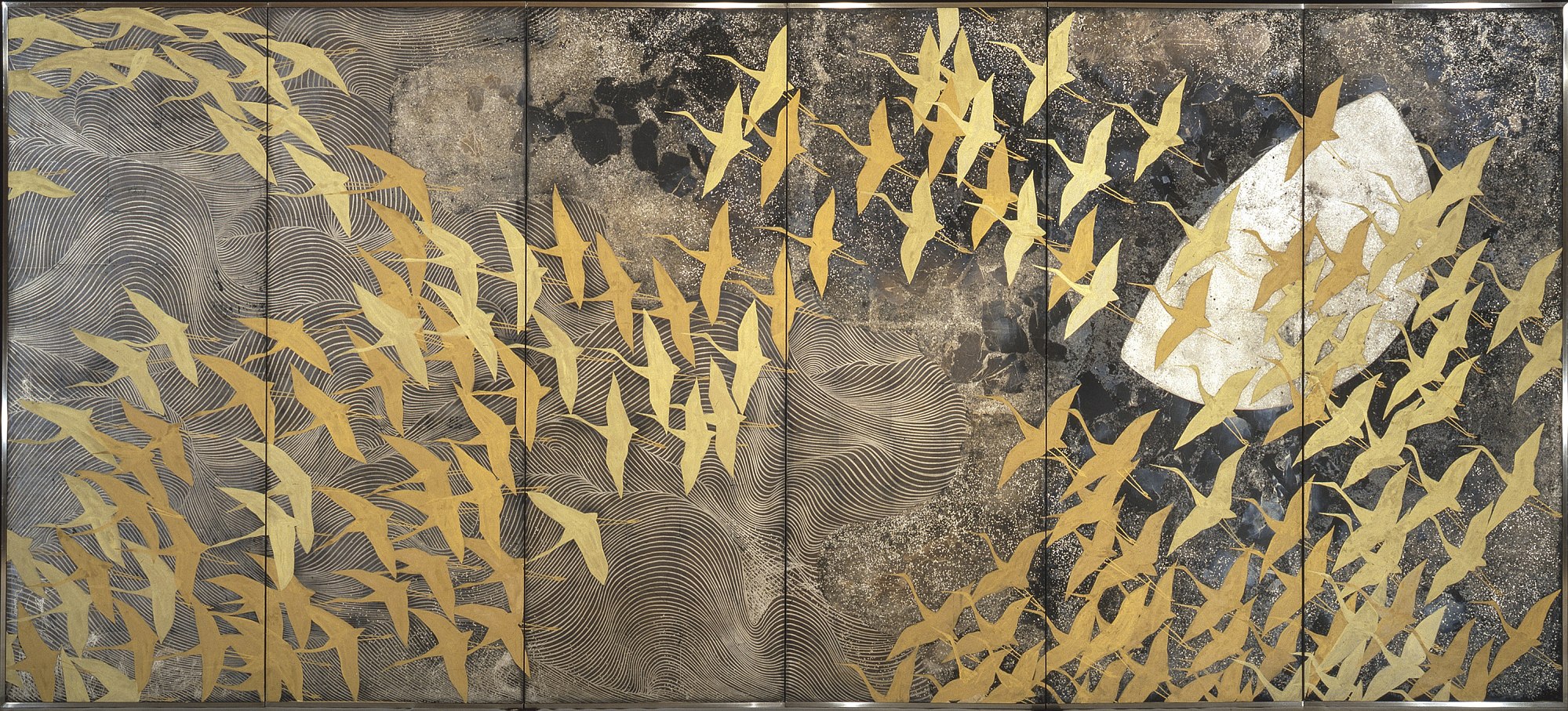

A Thousand Cranes

The broad surface of these two screens accommodates Kayama’s elegant homage to the decorative styles of Japan’s sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. There are several references to Sōtatsu and to Kōrin—in content and in technique. As a young man, Kayama had been deeply impressed by the exhibitions of works by Sōtatsu, Kōrin, and Henri Matisse (1869–1954) held at the Tokyo National Museum in 1947, which must have seemed like an oasis of beauty in the war-ravaged city. The son of a Kyoto textile designer and dyer, Kayama likely shared a sensibility with Sōtatsu and Kōrin.

He believed that “in the works of Sōtatsu one feels a true, rich abundance [and] that Tawaraya Sōtatsu was a luxurious person in every meaning of the word.” To Kayama, Sōtatsu was the only artist from whom such richness “gushed forth.” Many of his works apply the postmodern technique of disassembly and reconstruction. Classical Japanese paintings were often his primary sources.

A Thousand Cranes

Kayama Matazō (1927–2004)

Japan, 1970

Pair of six-panel folding screens

Color on silk

National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, J00716

Image 3 of 16

A Thousand Cranes

The broad surface of these two screens accommodates Kayama’s elegant homage to the decorative styles of Japan’s sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. There are several references to Sōtatsu and to Kōrin—in content and in technique. As a young man, Kayama had been deeply impressed by the exhibitions of works by Sōtatsu, Kōrin, and Henri Matisse (1869–1954) held at the Tokyo National Museum in 1947, which must have seemed like an oasis of beauty in the war-ravaged city. The son of a Kyoto textile designer and dyer, Kayama likely shared a sensibility with Sōtatsu and Kōrin.

He believed that “in the works of Sōtatsu one feels a true, rich abundance [and] that Tawaraya Sōtatsu was a luxurious person in every meaning of the word.” To Kayama, Sōtatsu was the only artist from whom such richness “gushed forth.” Many of his works apply the postmodern technique of disassembly and reconstruction. Classical Japanese paintings were often his primary sources.

A Thousand Cranes

Kayama Matazō (1927–2004)

Japan, 1970

Pair of six-panel folding screens

Color on silk

National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, J00716

Image 4 of 16

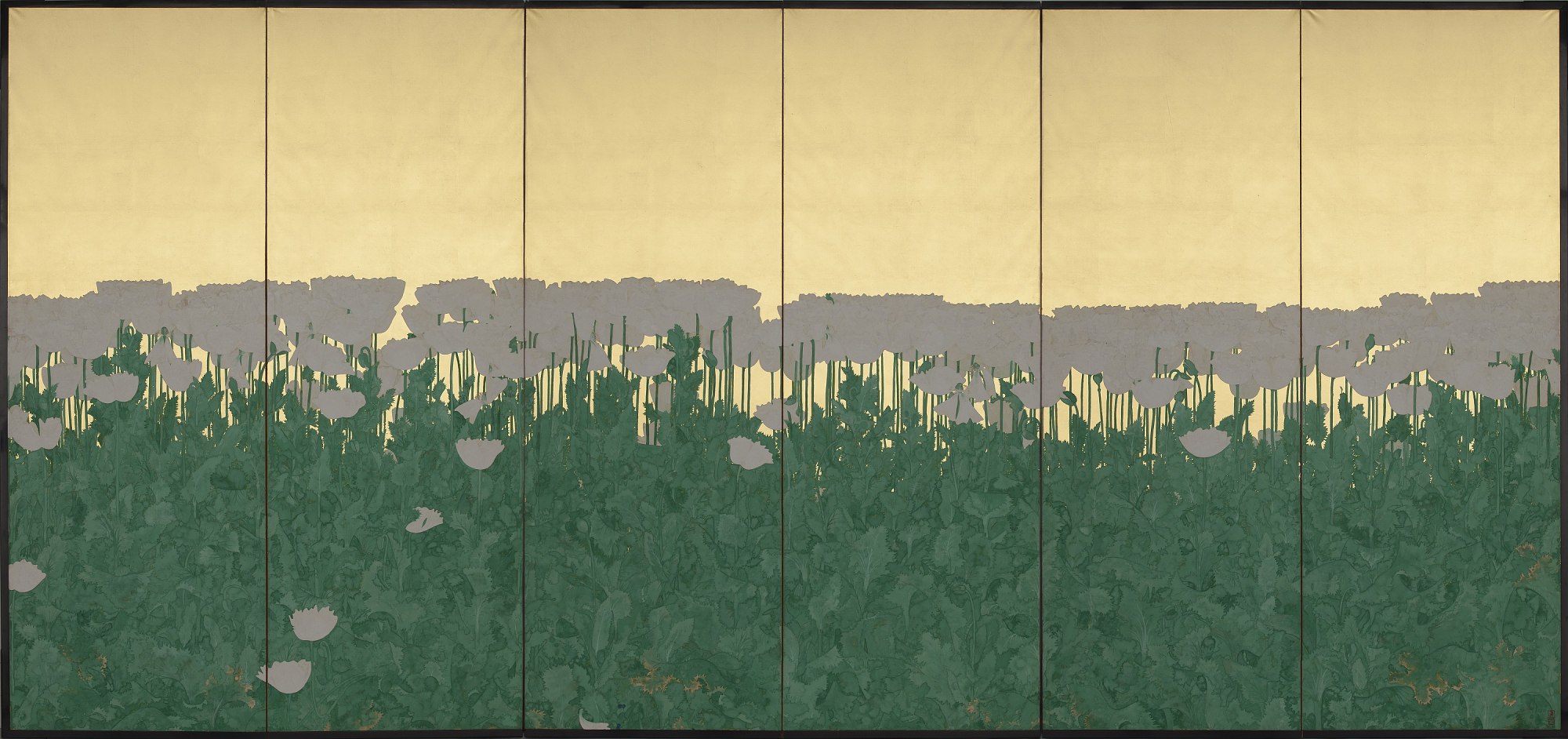

Poppies

In 1930s Japan, a fashion for neo-Rinpa paintings resulted in a number of distinguished works. Few were more iconic than this Maeda Seison rendering of poppies. As a young man, Maeda had been in a group of artists with access to the collection of Hara Sankei (1868–1939), a major art impresario and one of Charles Lang Freer’s good friends. At Hara’s villa in Yokohama, the young artist studied fine examples by Sōtatsu, Kōrin, and other artists.

The poppies create a gorgeous and rhythmic pattern that reflects Kōrin’s style rather than Sōtatsu’s. Like others in his generation, Maeda transformed Kōrin’s classic flat renderings into a more vividly lifelike surface, combining realism with a decorative sensibility. Poppies were a popular presence in the Sōtatsu and I’nen-seal repertoire, considered exotic because they had recently arrived in Japan.

Poppies

Maeda Seison (1885–1977)

Japan, 1930

Pair of six-panel folding screens

Color on paper

Hikaru Museum

Image 5 of 16

Morning Dew

It has been reported that Hirafuku Hyakusui observed the morning dew on the grass at Tokyo’s Yoyogi parade grounds for two years before painting this work—a meadow at dawn. Similar to other painters of the period, he sought to inject a degree of naturalism into the flattened, decorative features of the nihongastyle, whose practitioners claimed a lineage to Sōtatsu and Kōrin.

“Since the early to middle years of the Edo period,” he wrote, “Sōtatsu and Kōrin must be numbered first among the people who painted magnificent, fine work.” Hirafuku admired Sōtatsu for his ability to interpret the classics and because his compositions were more uninhibited than Kōrin’s.

Morning Dew

Hirafuku Hyakusui (1877–1933)

Japan, 1915

Pair of six-panel folding screens

Color on silk

Sannomaru Shōzōkan, Museum of the Imperial Collections, Tokyo

Image 6 of 16

Indian Corn Plants

Kokei studied classical Chinese and Japanese art, but he had a special interest in Sōtatsu. He painted this work in one of Sōtatsu’s favorite formats, the two-panel screen, and depicted maize (Indian corn), a subject frequently explored by the Tawaraya studio.

The painting allowed the artist to demonstrate his skills in the tarashikomi technique and to make subtle references to Sōtatsu’s works. These hints include the contrasting colors of the plant leaves as well as the blue-tinted gold color on the right and the pure gold color on the left. There is a strong resemblance to the powerful use of color in Sōtatsu’s The Gods of Wind and Thunder (Kenninji, Kyoto). Similar to Sōtatsu, Kokei took the delicate forms he saw in nature and gave them a stately elegance.

His technical explorations were not limited to imitations of Sōtatsu and other Rinpa painters. Like other artists of his day, Kokei used styles as well as materials from East Asian and Western painting traditions.

Indian Corn Plants

Kobayashi Kokei (1883–1957)

Japan, 1939

Pair of two-panel folding screens

Color on paper

National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, J00511

Image 7 of 16

Flowing Fans

In early twentieth-century Japan, several groups supported the growing interest in new painting styles. The Yamato-e Revival Society, for example, focused on research and seeking access to original works; Hōshun joined that group in 1923. He was an avid student of classical Japanese painting styles. Like his contemporaries, he experimented with hybrid techniques, including uncharacteristically level perspective and the flat yamato-e (indigenous Japanese painting) style. He also had a background in oil painting.

Hōshun was extremely interested in the Rinpa school and collected works by Sōtatsu, Kōrin, and their followers. He explored Sōtatsu’s depictions of classical literature. Azusayumifrom Tales of Ise is from Hōshun’s collection. He wrote detailed analyses on Sōtatsu’s and Kōrin’s work, paying particular attention to their painting techniques.

Many of the techniques he used—the gold, silver, and the pooled pigments of tarashikomi—pay homage to Sōtatsu. Hōshun was cleverly subversive, however, and inserted a sense of realism—fans floating on a stream rather than a screen.

Flowing Fans

Yamaguchi Hōshun (1893–1971)

Japan, 1930

Two-panel folding screen

Color on paper

Hōshun Yamaguchi Memorial Hall

Image 8 of 16

Bamboo

Fukuda Heihachirō trained in Kyoto under the renowned Takeuchi Seihō (1864–1942) and other prominent painters. He was deeply committed to realism, particularly in the 1910s and 1920s. In later years, still sketching from real life, he moved to a flattened, pure-form decorative style. He acknowledged that his concepts were inspired by the masters, Sōtatsu and Kōrin.

Bamboo depicts the meticulous, small differences among a group of six bamboo plants and shoots. It has a simple and direct composition, with the plants lined up in a straight row. Its origins lie in Sōtatsu’s designs for poetry scrolls and other works.

A few years after he created this work, Heihachirō challenged the long-standing convention of painting bamboo in green pigment, saying that it “has no meaning because it is simple tradition, repeated dutifully without introspection or consideration. Even now, I have never … [seen] verdigris in bamboo.”

Bamboo

Fukuda Heihachirō (1892–1974)

Japan, 1942

Painting

Color on silk

National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, J00101

Image 9 of 16

Puppy

Kobayashi Kokei was profoundly influenced by the 1913 Sōtatsu exhibition in Tokyo and was one of the few artists invited to study original paintings by Sōtatsu, Kōrin, and other Rinpa masters in the Hara Sankei (1868–1939) collection. His peers Maeda Seison (1885–1977) and Yasuda Yukihiko (1884–1978), who also visited Hara’s collection, were champions of Sōtatsu, whose works greatly influenced many modern nihonga artists. Kokei saw the beauty depicted in classical works. However, his approach was utterly different from that of his contemporaries, particularly in his adaptations of Sōtatsu’s ink-painting styles.

Puppy demonstrates a careful understanding of the tarashikomi pooling effect and clear outlining, recalling Sōtatsu’s favored horinuri technique, which paid homage to the structural line. Rather than using bold pattern and vibrant color, Kokei strived to capture Sōtatsu’s graceful restraint.

Puppy

Kobayashi Kokei (1883–1957)

Japan, 1948

Hanging scroll

Ink and colors on paper

Private collection

Image 10 of 16

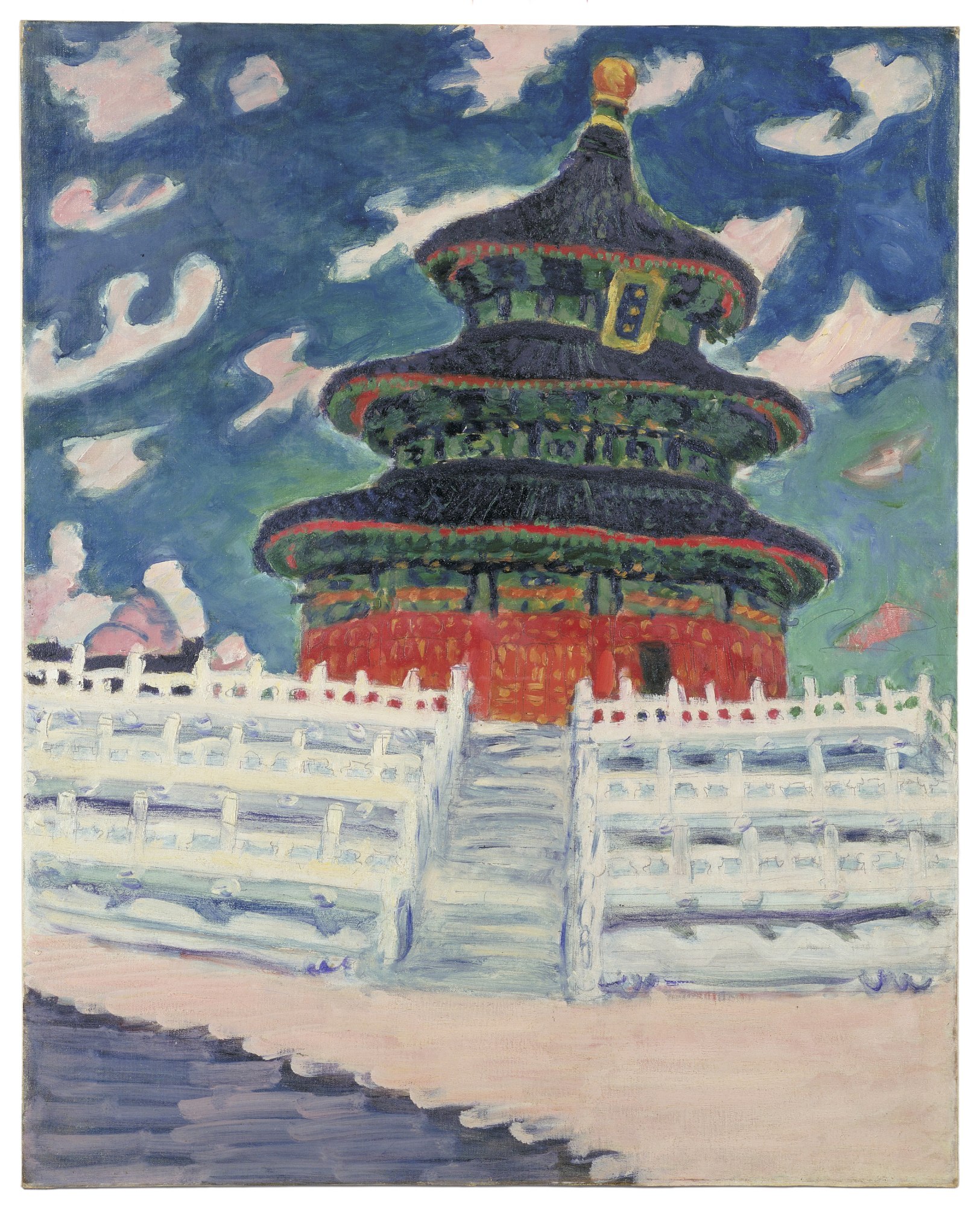

Tiantan in the Clouds

The Tiantian Tower in Beijing is a sacred site, where Ming and Qing emperors conducted rituals that honored heaven. Umehara was one of many Japanese artists who found thematic inspiration in travels to China, especially in the 1930s. Trained by Asai Chū (1856–1907), one of the first Japanese artists to study oil painting in Europe, Umehara also resided in France for five years, studying with Renoir and absorbing impressionism firsthand. After World War I, he pursued a unique form of oil painting that incorporated traditional Japanese media, such as gold paint and mineral pigment, and established a decorative idiom that joined East to West. Here, Umehara’s bold composition, distortion of forms, and rhythmic patterns capture the essence of Sōtatsu’s work. Described on one occasion as the “Sōtatsu of modern oil painting,” Umehara was a diligent student of works by the seventeenth-century artist and his contemporaries. He owned a small Sōtatsu painting on decorative paper.

Tiantan in the Clouds

Umehara Ryūzaburō (1888–1986)

Japan, 1939

Painting

Oil on canvas

National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, 000188

Image 11 of 16

Irises

Fukuda Heihachirō trained in Kyoto under the renowned Takeuchi Seihō (1864–1942) and other prominent painters. His stylistic development took many turns and included a devotion to realism in the 1910s and ’20s. In later years, still sketching from real life, he moved to a flattened, pure-form decorative style. He acknowledged that his concepts flowed from the masters Sōtatsu and Kōrin.

These irises are a clear homage to a famous painting by Kōrin. However, the pull of realism is strong. The careful, individualized attention paid to the blossoms and leaves, each one delicately rendered, mixes Rinpa-style patterning with the techniques of exquisite observation.

Late in life Heihachirō observed, “In most cases, because of my faith in reality, I move with the aim to penetrate the real; however, because I love Kōrin and Sōtatsu, I somehow get involved in decorative art. I reflected on this tendency day and night, and I realized that whether I have become decorative or realist does not matter to me. The problem is the content.”

Irises

Fukuda Heihachirō (1892–1974)

Japan, 1934

Painting

Color on silk

National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, J00067

Image 12 of 16

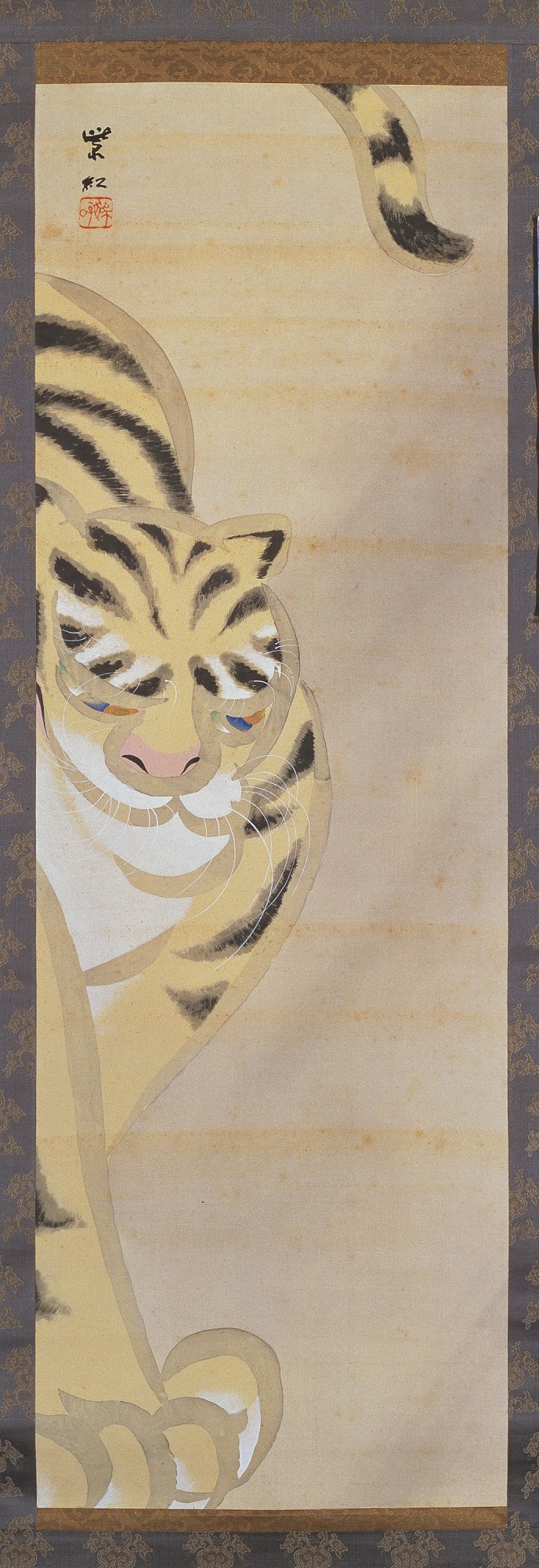

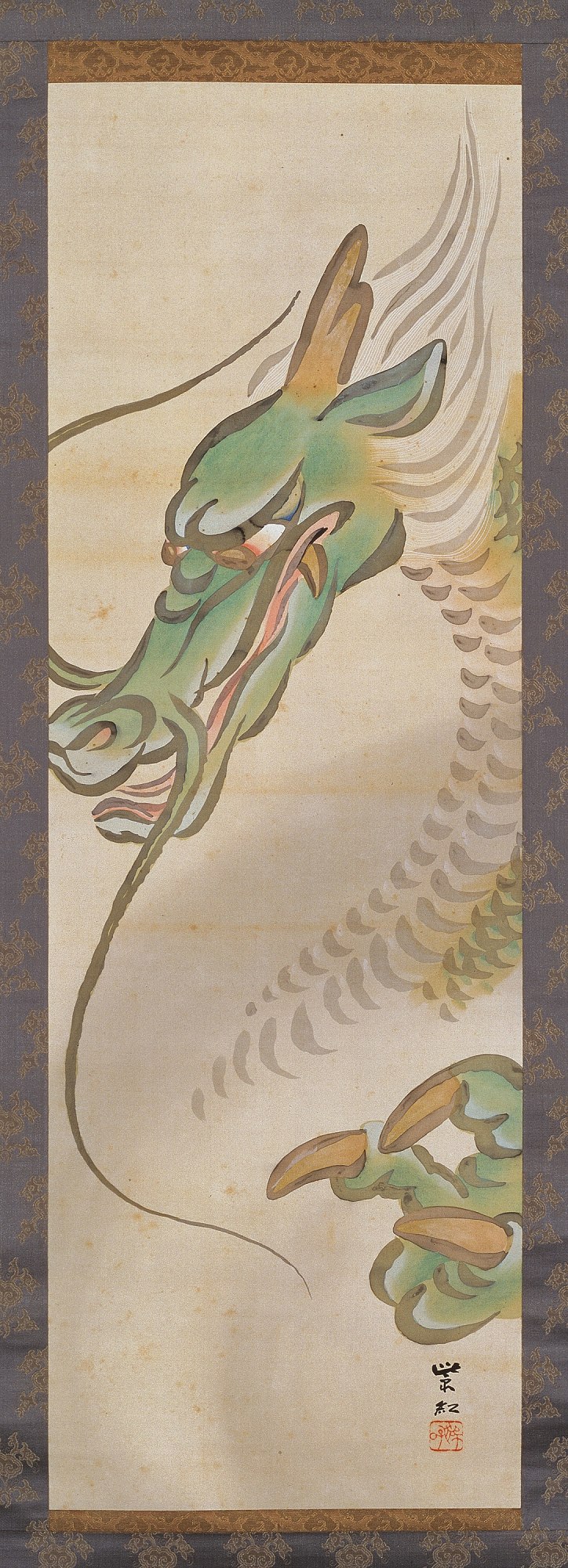

Dragon and Tiger

Imamura Shikō greatly admired Sōtatsu. When scholar Okakura Kakuzō (1863–1913) asked with which historical figure he most identified, Imamura replied “Sōtatsu.” This was in 1907 when Sōtatsu was barely known, making his answer all the more remarkable.

Imamura developed a brightly translucent method of coloration. His paintings of these Sōtatsu-like subjects were not an obvious homage. Yet the unlikely colors of green applied to the dragon and white to the tiger seem to be humorous nods to Sōtatsu’s famed The Gods of Wind and Thunder. He constantly experimented with ways to reinvigorate and improve the nihonga painting style. He successfully combined elements of impressionism and the Japanese Nanga style, an interpretation of Chinese literati painting modes. Unfortunately, his promise would remain unfulfilled as he passed away in 1916 at the age of thirty-five.

Dragon and Tiger

Imamura Shikō (1880–1916)

Japan, 1913

Pair of hanging scrolls

The Museum of Modern Art, Saitama

Image 13 of 16

Dragon and Tiger

Imamura Shikō greatly admired Sōtatsu. When scholar Okakura Kakuzō (1863–1913) asked with which historical figure he most identified, Imamura replied “Sōtatsu.” This was in 1907 when Sōtatsu was barely known, making his answer all the more remarkable.

Imamura developed a brightly translucent method of coloration. His paintings of these Sōtatsu-like subjects were not an obvious homage. Yet the unlikely colors of green applied to the dragon and white to the tiger seem to be humorous nods to Sōtatsu’s famed The Gods of Wind and Thunder. He constantly experimented with ways to reinvigorate and improve the nihonga painting style. He successfully combined elements of impressionism and the Japanese Nanga style, an interpretation of Chinese literati painting modes. Unfortunately, his promise would remain unfulfilled as he passed away in 1916 at the age of thirty-five.

Dragon and Tiger

Imamura Shikō (1880–1916)

Japan, 1913

Pair of hanging scrolls

The Museum of Modern Art, Saitama

Image 14 of 16

Passage

This scene captures the beauty in a moment of summer domesticity as mother, daughter, and dog parade under parasols, somehow fresh in the heat of the day. The origin of the image is less than obvious. The artist was inspired by an image in China’s famed Longmen Caves (circa sixth century CE) that depicts a passionate young acolyte engaged in the Buddhist practice of achieving an “empty” mind (Japanese: mushin). Although knowing that this work refers to Buddhist iconography enhances one’s appreciation, the viewer still is left to wonder about the three figures. Ogura painted this work in 1966, at a time of increased Japanese interest in Buddhism in Asia and the Silk Road.

Her approach to painting was rooted in her study of early twentieth-century modernists, including Picasso, Braque, and Matisse. She also admired Sōtatsu and once called him, Matisse, and the monk-calligrapher Ryōkan (1758–1813) the three most important artists in her personal pantheon: “They are the best, and there is warmth and ease there. They are not stiff, but full of joy.”

Passage

Ogura Yuki (1895–2000)

Japan, 1966

Painting on board

Tokyo University of the Arts

Image 15 of 16

The Gods of Wind and Thunder

Maeda Seison, whose Poppies is also on display in this gallery, made no secret of his profound admiration for Sōtatsu and the artists who developed the Rinpa tradition. With these iconic images of the gods of wind and thunder, the artist placed himself in the lineage of Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) and Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828), who had created their own versions as an homage to Sōtatsu. Seison abandoned the two-panel folding screen pioneered by Sōtatsu and instead created a new, vertical composition, enclosing the two gods within a single painting. The wind god turns his back to the viewer, and the thunder god is without his drum. Seison also used a billowing ink outline and touches of color—the opposite of Sōtatsu’s approach.

The Gods of Wind and Thunder

Maeda Seison (1885–1977)

Japan, 1949

Painting

Ink and color on paper

Seki Art Gallery

Image 16 of 16

Legacy of Waves

Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716), scion of a Kyoto textile merchant, traced part of his ancestry to the sister of calligrapher Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637) and thus had privileged knowledge of works by Sōtatsu. Kōrin recognized Sōtatsu’s powerful stylistic innovations and adapted and transmitted them—so much so that his name became synonymous with the style. The term Rinpa derives from the last syllable of Kōrin’s name plus the designator for “group.”

Rinpa artists paid homage to Sōtatsu’s original creations. On exhibition are tributes to his Waves at Matsushima screens by a number of artists, although they sometimes credited Kōrin. (For more examples of Rinpa art, see the Bold and Beautiful exhibitions, on view in the Freer Gallery of Art through January 3, 2016).

The title Waves at Matsushima seems to have been given to the Sōtatsu screens around the time they were purchased by Freer Gallery founder Charles Lang Freer, although the images were not originally connected with that site. During the mid-to-late Edo period, however, the islands of Matsushima, off the northeast coast of Japan’s Honshu Island, were regarded as one of Japan’s famous views, and various iterations of the Waves came to be associated with Matsushima.

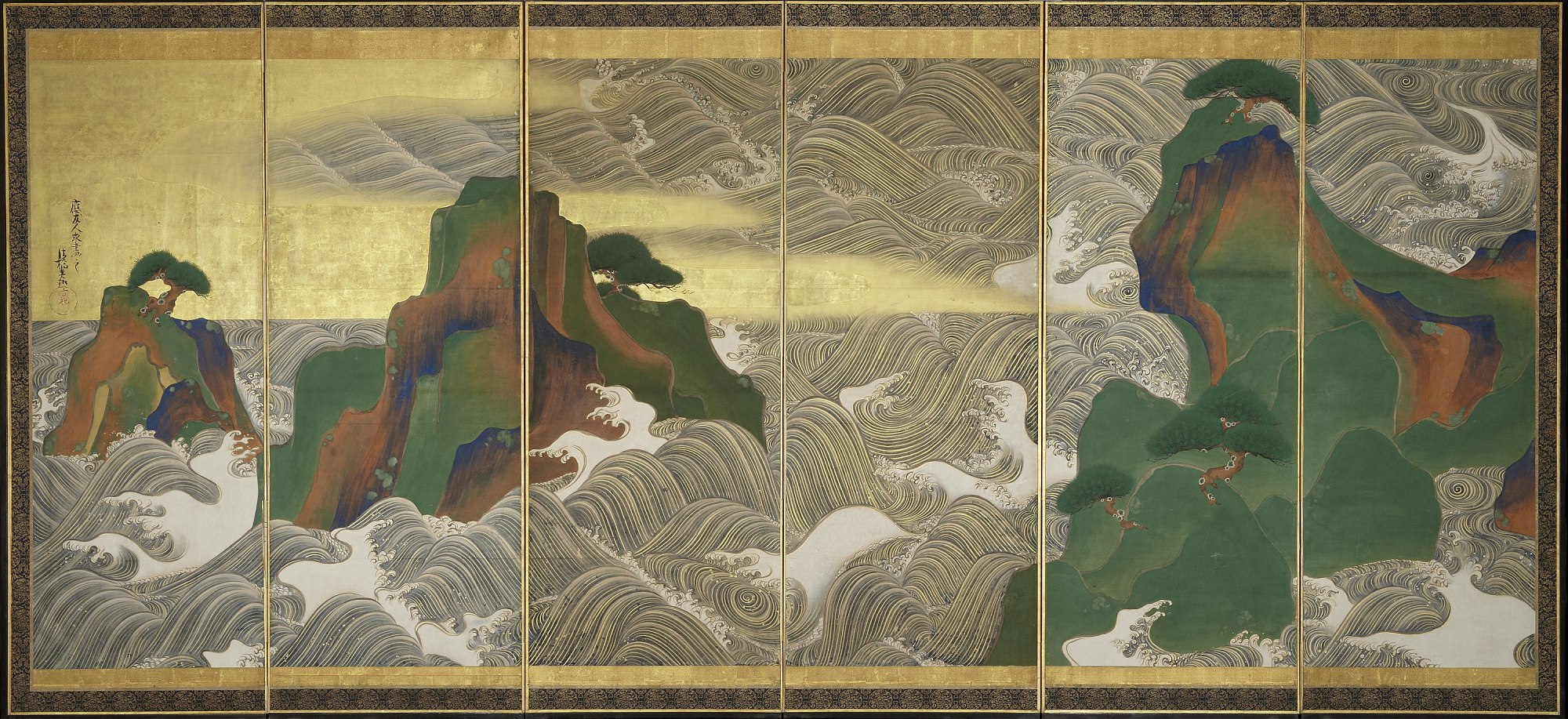

Waves at Matsushima

Ogata Kōrin was the most famous exponent of the Sōtatsu style. Born into a wealthy merchant family who operated Kariganeya, a prestigious drapery shop in Kyoto, he embarked on a painting career when he reached middle age. He created a number of works based on Sōtatsu paintings, including Waves of Matsushima and The Gods of Wind and Thunder at Kenninji, a temple in Kyoto. This painting approximates Sōtatsu’s famous version of the Waves theme but also differs in key ways. Kōrin likely saw the image of a pine-studded rock as a fine template for describing the Daoist paradise of Mount Penglai, which was associated with immortality and longevity. Although this work has been heavily retouched in the rocks and pines and possibly around the signature and seal, it is nonetheless a masterful work by Kōrin.

Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908), scholar, collector, connoisseur, and advisor to Charles Lang Freer, acquired this screen in 1880 while he was living in Japan. In 1886, he sold it to Dr. Charles Goddard Weld (1857–1911), a wealthy Boston physician.

Waves at Matsushima

Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716)

Japan, early 18th century

Six-panel screen

Ink, color, and gold on paper

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Fenollosa-Weld Collection, 11.4584

Image 1 of 6

Waves at Matsushima

Ogata Kōrin adapted and disseminated many Sōtatsu works; those adaptations were further codified in woodblock-printed form and attributed to Kōrin himself at the centennial anniversary of his death. See One Hundred Pictures by Kōrin (Kōrin hyakuzu) elsewhere in this gallery; its images had been altered several times since Sōtatsu’s original productions. Suzuki Kiitsu (1796–1858) was a painter based in Edo (Tokyo’s name before 1868) who elaborated on Kōrin’s style, as did his teacher Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1829). The placement of various elements suggests that Kiitsu might have used the printed-book image as a model. His Waves at Matsushima reflects the Edo taste for a smoother, more polished approach to Rinpa painting.

Waves at Matsushima

Suzuki Kiitsu (1796–1858)

Japan, ca. 1830

Pair of sliding-door panels (kobusuma)

Ink and colors on paper

Feinberg Collection

Image 2 of 6

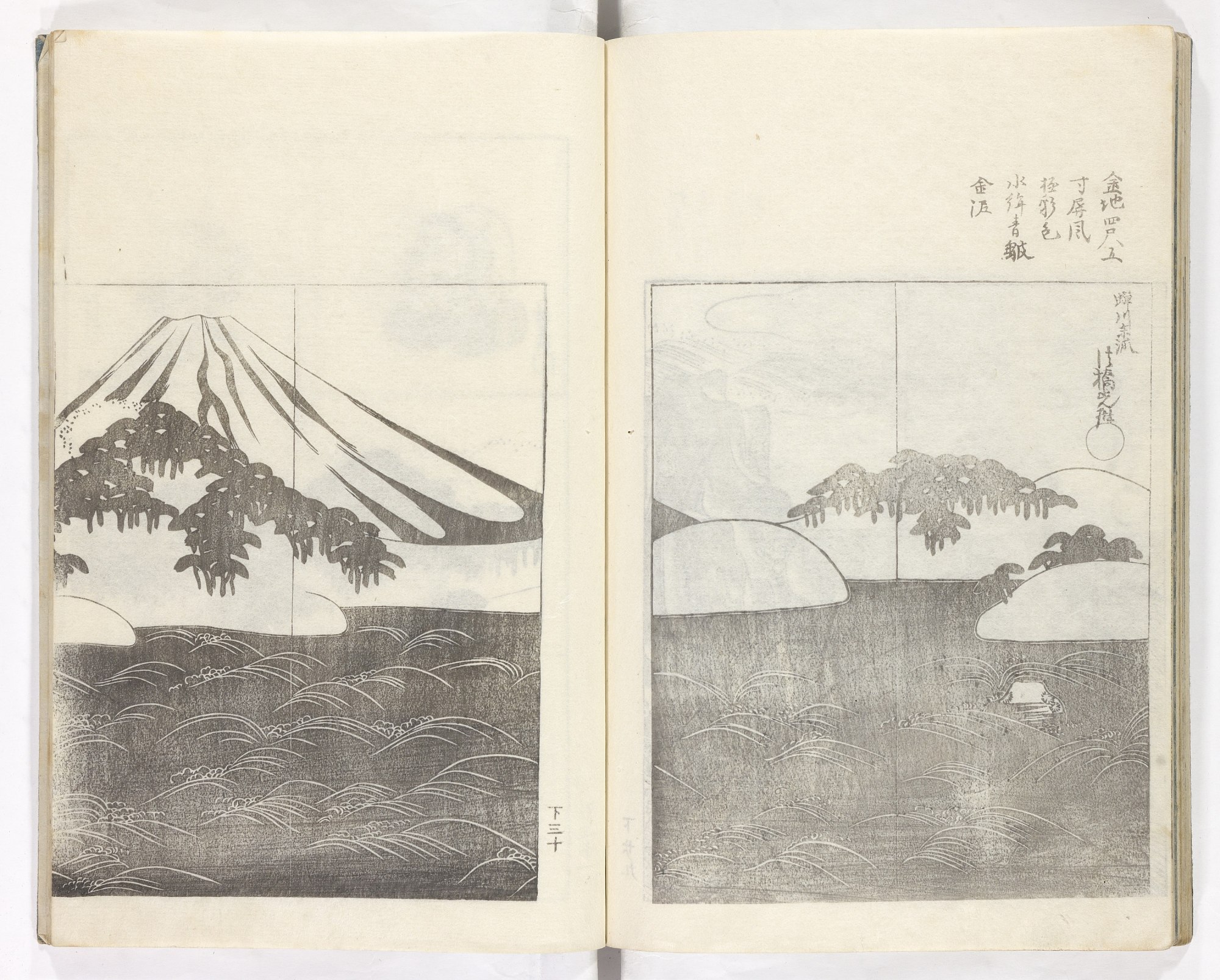

Kōrin hyakuzu kōhen

Few vehicles were more important to the dispersal of the Rinpa style than One Hundred Paintings by Kōrin (Kōrin hyakuzu). The undated, woodblock-printed book was produced as part of the celebrations surrounding the one-hundredth anniversary of Kōrin’s death in 1815. Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828), the most distinguished living painter practicing Kōrin’s style, organized a memorial service in Edo and produced an exhibition of his forerunner’s paintings. This book features paintings shown at the exhibition and additional others, for a total of ninety-nine. Eleven years later, another edition was produced with 103 images.

Kōrin hyakuzu kōhen

Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828)

Japan, 1826

Volume 2, woodblock-printed book

Ink on paper; paper covers

Purchase—The Gerhard Pulverer Collection, Museum funds, Friends of the Freer and Sackler Galleries and the Harold P. Stern Memorial fund in appreciation of Jeffrey P. Cunard and his exemplary service to the Galleries as chair of the Board of Trustees (2003-2007)

Freer Gallery of Art, FSC-GR-780.476.1

Image 3 of 6

Waves at Matsushima and Mount Fuji

Until recently, these screens were known only from the 1826 edition of the book One Hundred Pictures by Kōrin (Kōrin hyakuzu), on view in the next section. This exhibition provides the first occasion to study these unusual works and connect them to Sōtatsu’s grand theme. The Kōrin seal and signature are at odds with the painting techniques, which suggest another hand. The Waves half demonstrates overly meticulous brushwork while the Mount Fuji half seems oversimplified. (Compare it to the screen from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which seems to have been produced much earlier.) Some modern scholarship suggests that side-by-side placement of the two images—mountain and roiling waters—emerged from nō drama texts connecting the Miho area (from where Mount Fuji can be viewed) to legendary “floating islands” related to the mythical Mount Penglai, the isle of immortality.

Waves at Matsushima and Mount Fuji

Attributed to Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716)

Japan, 19th century

Pair of six-panel folding screens

Ink, colors, and gold on paper

Private collection

Image 4 of 6

Waves at Matsushima and Mount Fuji

Until recently, these screens were known only from the 1826 edition of the book One Hundred Pictures by Kōrin (Kōrin hyakuzu), on view in the next section. This exhibition provides the first occasion to study these unusual works and connect them to Sōtatsu’s grand theme. The Kōrin seal and signature are at odds with the painting techniques, which suggest another hand. The Waves half demonstrates overly meticulous brushwork while the Mount Fuji half seems oversimplified. (Compare it to the screen from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which seems to have been produced much earlier.) Some modern scholarship suggests that side-by-side placement of the two images—mountain and roiling waters—emerged from nō drama texts connecting the Miho area (from where Mount Fuji can be viewed) to legendary “floating islands” related to the mythical Mount Penglai, the isle of immortality.

Waves at Matsushima and Mount Fuji

Attributed to Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716)

Japan, 19th century

Pair of six-panel folding screens

Ink, colors, and gold on paper

Private collection

Image 5 of 6

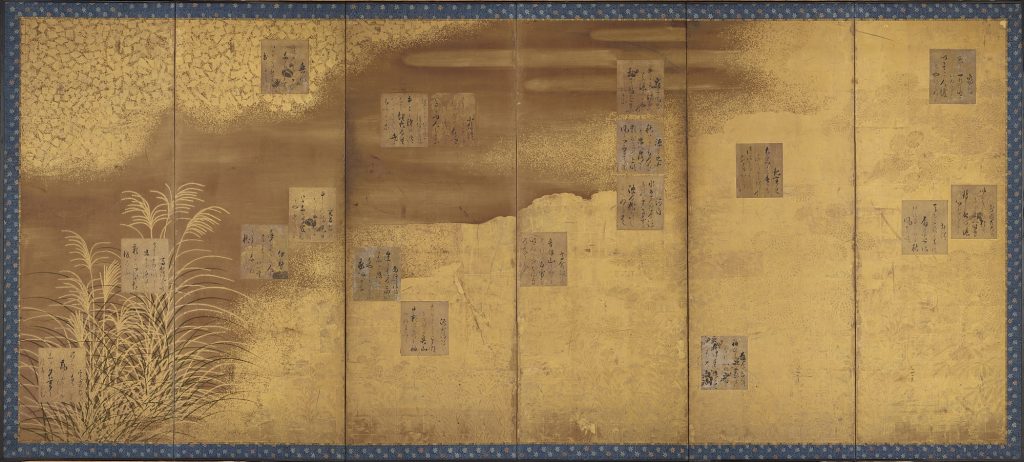

Boats on the Sea

While these screens resemble the Freer’s Waves at Matsushima, they portray a more general topic—“pine shores.” This yamato-e(traditional Japanese painting) subject developed during the Muromachi period (1333–1573). Traces of thirty-six poem sheets (shikishi) indicate that the screens were once covered with waka poetry (thirty-one-syllable verses). This explains the overly expansive depiction of clouds, which provide blank spaces for the poetry. Other screens attributed to Sōtatsu feature shikishi pasted over a large representational image. These screens both bear the signature Sōtatsu Hokkyō and the round vermilion seal Taiseiken typically associated with the artist; here, however, the seal impression differs from the standard. The “Matsushima” theme was in the repertoire of seventeenth-century painters, and the Tawaraya atelier may have produced this work. However, that is the extent of any relationship to the Waves at Matsushimascreens, which are not generic but have a highly specific celebratory intention.

Boats on the Sea

Studio of Tawaraya Sōtatsu (act. ca. 1600–40)

Japan, mid-17th century

Pair of six-panel folding screens

Ink, colors, gold, and silver on paper

Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, L2015.33.2.1-.2

Image 6 of 6

Whose Sleeves?

Charles Lang Freer acquired these screens in 1907, a year after he purchased Waves at Matsushima. He surely was pleased that his treasured Sōtatsu screens were referenced in an Edo period (1615–1868) genre of painting called tagasode, often translated as “whose sleeves?” The screens celebrate material abundance, casually displayed. The viewer is invited to be a voyeur, to savor the gorgeous clothing and luxury items that adorn the private interior. Robes draped carelessly over folding screens leave the viewer to ponder where the owner might be; romping cats add to the scene’s erotic tone.

The specificity of the screen depicted in the interior is striking. A six-panel screen—its full image partially obscured by the tossed garment—seems to be the right screen of Waves at Matsushima; in the lower-right section is an approximation of the Taiseiken seal, also found on the Matsushima screens. Missing, however, is any attempt to replicate Sōtatsu’s signature. Close examination of the depiction and position of the islands suggests that the image is closer to a version attributed to Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (also on view in this gallery). Additional views.

Whose Sleeves?

Charles Lang Freer acquired these screens in 1907, a year after he purchased Waves at Matsushima. He surely was pleased that his treasured Sōtatsu screens were referenced in an Edo period (1615–1868) genre of painting called tagasode, often translated as “whose sleeves?” The screens celebrate material abundance, casually displayed. The viewer is invited to be a voyeur, to savor the gorgeous clothing and luxury items that adorn the private interior. Robes draped carelessly over folding screens leave the viewer to ponder where the owner might be; romping cats add to the scene’s erotic tone.

The specificity of the screen depicted in the interior is striking. A six-panel screen—its full image partially obscured by the tossed garment—seems to be the right screen of Waves at Matsushima; in the lower-right section is an approximation of the Taiseiken seal, also found on the Matsushima screens. Missing, however, is any attempt to replicate Sōtatsu’s signature. Close examination of the depiction and position of the islands suggests that the image is closer to a version attributed to Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (also on view in this gallery).

Kōrin hyakuzu kōhen

Few vehicles were more important to the dispersal of the Rinpa style than One Hundred Paintings by Kōrin (Kōrin hyakuzu). The undated, woodblock-printed book was produced as part of the celebrations surrounding the one-hundredth anniversary of Kōrin’s death in 1815. Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828), the most distinguished living painter practicing Kōrin’s style, organized a memorial service in Edo and produced an exhibition of his forerunner’s paintings. This book features paintings shown at the exhibition and additional others, for a total of ninety-nine. Eleven years later, another edition was produced with 103 images.

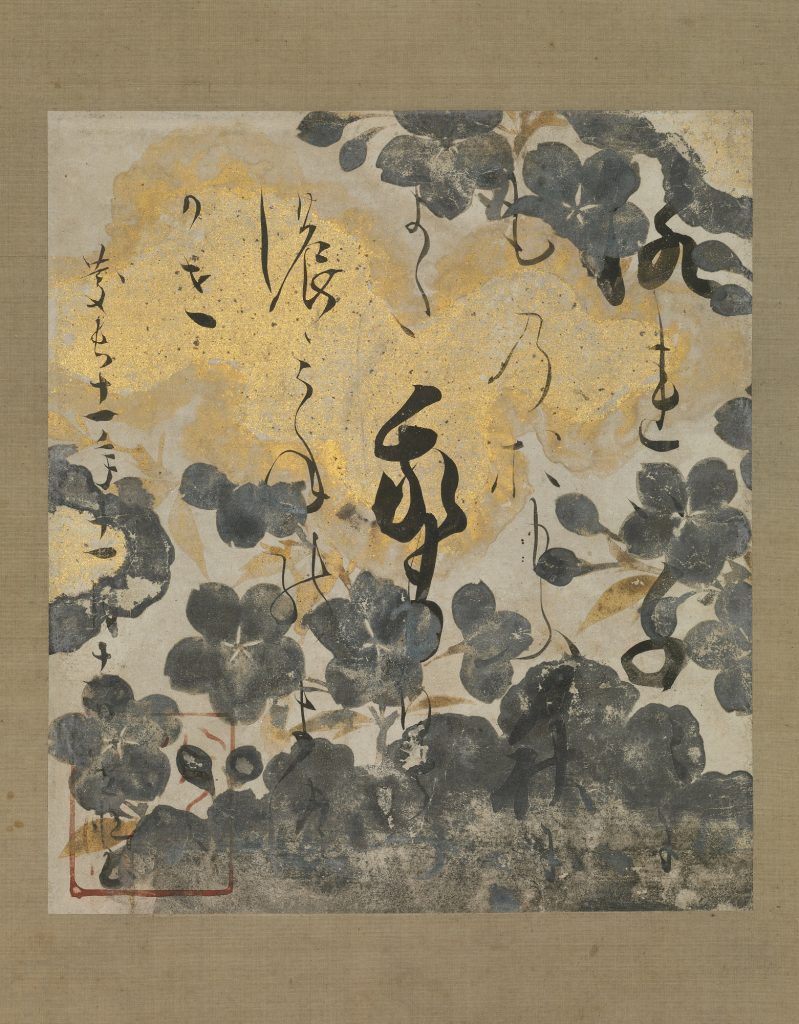

The I’nen Garden

The I’nen seal is a mark that was placed on several Tawaraya works during Sōtatsu’s lifetime, an indication that they were produced either by his own hand or by his studio. The seal was used with greater frequency by the studio’s artists after Sōtatsu’s death in circa 1640.

Many I’nen seal works depict flowers and plants. The Japanese had always sought metaphors for the complexities of the human heart in the world of nature. But beginning in the seventeenth century, there was a marked increase in their interest in botany, exotica imported from afar, scientific examination and categorization of plant types, and rikka, an early form of ikebana flower arrangement. Personal gardens varied greatly in style, engaging both the heart and the intellect. People often gave seedlings, plants, and cut flowers as gifts. The Tawaraya studio and the artists who used the I’nen seal gained commissions that reflected this newly intense interest. In the decades after his death, Sōtatsu’s techniques and creativity became almost synonymous with images of flowering beauty.

Sōtatsu’s Methods: The Visibility of Craft

Sōtatsu dealt with extremely refined subject matter—ancient aristocratic poetry and illustrated court and religious narratives—but he sought to reveal the construction and inner workings of an image rather than polish the “building blocks” until they were invisible. Skilled in both the production of supporting materials—i.e., books, folding fans, screens, and scrolls—as well as the forms that graced their surfaces, Sōtatsu was first and foremost a craftsman. Indeed, it is “craft” that he apparently wanted his audience to appreciate in his work.

As you explore this exhibition, look for the three techniques Sōtatsu used in varying degrees throughout his career: tarashikomi, horinuri, and kataoshi.

Tarashikomi (たらしこみ) is a technique of pooling pigment or ink in partially dried layers, allowing random, semi-translucent shapes to take form. The patterns that result suggest both dimensionality and ephemerality, and thus uncertainty.

Horinuri (彫り塗り) is a style of painting in multiple colors in which ink underdrawings—outlines of human figures and other shapes—remain partially visible. In the more traditional style, tsukuri-e, the outline is completely covered with opaque pigments. Horinuri honors the tradition of works created with brushed ink, which in East Asia is considered to be the skill par excellence.

Kataoshi (型押し) are stamped patterns, frequently seen on the paper Sōtatsu and his studio prepared for calligraphers. The artist forms shapes—cranes, bamboo, flowering plants—with inks that have varying degrees of thickness, and the patterns that result are both manipulated and random.

Peonies and Lilies

In this work, lilies and peonies are interspersed with small, white, five-petal flowers. The plant to the left of the empty space below appears to be bracken. The flowers are painted delicately with light ink outlines, and red and white pigment has been added to the petals. The leaves, on the other hand, are rendered without outline in the “boneless” manner (mokkotsubyō), using the “dripped in” (tarashikomi) technique with watery ink, to which small amounts of green pigment have been added. The round red relief seal I’nen is pressed in the lower-right corner. The substantial use of ink in this botanical work recalls the style developed by Kitagawa Sōsetsu (active mid-seventeenth century), head of the Tawaraya studio in the generation following Sōtatsu’s death. This painting represents one of the directions in which the I’nen style developed.

Coxcombs, Maize, and Morning Glories

Charles Lang Freer acquired this screen—and its counterpart on the other side—in a reverse order of their sequence of production. This ghostly image, a now-faded rendering on a silver ground, is the earlier work and was Freer’s second purchase. It is considerably damaged and partially illegible. Even in skeletal form, however, it expresses a vitality that is somewhat lacking in the subdued and more uniform later work.

Coxcombs, Maize, and Morning Glories

This work on a half-gold and half-silver ground and the other screen in this case were acquired by Charles Lang Freer as he sought to grasp the stylistic distinctions in the little-known world of Sōtatsu and his associates. Freer and scholar Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) attributed both screens to Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637), but the use of gold lines to render leaves is a Sōtatsu technique. The subject—the exotic maize plant—made its first appearance in Kyushu in the last quarter of the sixteenth century and moved gradually eastward. The coxcomb arrived in Japan much earlier. Together, the two plants were considered an auspicious symbol of vitality and resilience.

Mimosa Tree, Poppies, and Other Summer Flowers

The mimosa (nemunoki) tree is indigenous to Japan but was infrequently depicted in paintings . This work is dominated by the mimosa canopy sheltering the grasses and flowers underneath. The plants are rendered in the “boneless” style (i.e., without outline). The compositional formula—an expansive umbrella with no reference to trunk or roots—is associated with paintings found in Biliang, China, indicating a possible influence from that region. Other paintings with the I’nen seal sometimes employ this device, but this four-panel folding screen is a very early example. The dimensions suggest that the painting was originally created for sliding-door panels (fusuma). It bears the I’nen seal, which indicates that it is by a Tawaraya studio artist.

Summer and Autumn Flowers

This is one of a large number of grass-and-flower paintings bearing the I’nen seal. The genre incorporates a range of styles from relatively realistic to highly idealized; the Freer screen is decidedly lacking in realism. The trend toward idealism seems to have increased with the significant demand for grass-and-flower paintings in the decades after Sōtatsu’s death. Uncertain draftsmanship and a confusing arrangement of seasonal and other motifs suggest a decreasing reliance on direct observation of nature as well as diminished technical abilities. Thus, this screen can be dated to a time when such works began to be created in large numbers.

Trees

Precision, variety, and a remarkable composition are features of this I’nen seal painting. Lined up across a gold-foil ground are all types of evergreens (associated with vitality and longevity)—not in full display but as if viewed from a window. Painters of the Kanō school developed the genre of “standing trees” (ryūboku zu), but Trees differs greatly from Kanō examples. The painter clearly was aware of the striking effects of green pigment against gold foil. His powerful diagonals and bold color recall large Sōtatsu screens, which were perhaps inspired by smaller-scale decorative paper schemes. While some I’nen-style plant paintings fill the entire space, this composition reverts to an older painting style characterized by a tight geometry and a constricted sense of abundance. Similar to Dragons and Clouds, it is hard to determine the left and right screens based on the seal position, because they can be displayed either way.

Trees

Master of the I’nen Seal (1600–30), Sōtatsu school

Japan, mid-17th century

Pair of six-panel folding screens

Ink, colors, and gold on paper

Freer Gallery of Art, F1962.30-31

Image 1 of 2

Trees

Master of the I’nen Seal (1600–30), Sōtatsu school

Japan, mid-17th century

Pair of six-panel folding screens

Ink, colors, and gold on paper

Freer Gallery of Art, F1962.30-31

Image 2 of 2

Flowers and Grasses of the Four Seasons

Some seventy different types of grasses, flowers, vegetables, and shellfish fill the surfaces of this pair of screens. Bouquet-like arrangements set on a gold background indicate a decorative intention, but closer examination reveals technically careful and delicate renderings and a complex coloration that aims for realism. This painting is at once bountiful and charmingly encyclopedic. It bears the I’nen seal; thus, it is likely a studio work that responded to the heightened interest in botanical subject matter in seventeenth-century Japan—during Sōtatsu’s later years and for many years afterward. Plant life emerged from its traditional role as seasonal indicator and metaphor for ephemerality and became something admired for its inherent beauty. The Tawaraya atelier maintained significant connections to taste-setting patrons at the court, merchants, and warrior elites and served those groups with gorgeous and accurate studies of plants.

Inkwork

Japanese artists were known for using media appropriate for the subject matter. Images depicting traditional Japanese narrative tales typically were rendered in opaque colors with outlines created in ink and later obscured by color overlay. Ink monochrome was closely associated with Chinese styles, particularly those transported to Japan via Zen Buddhism. Ink-based forms created with modulated strokes and layered washes suggested introspection and spiritual exploration.

In his application of the tarashikomi technique—random pools of pigment and ink—Sōtatsu subtly subverted the tradition. He used ink to depict the ordinary subjects of everyday life—puppies and plants—in a style that took on an allusive ambiguity. Instead of the solid, opaque colors traditionally associated with narrative painting, Sōtatsu used pooled ink and randomly changing color fields to indicate the underlying Buddhist theme: the unreliability of the visual world.

The Zen Priest Chōka

Niaoke, referred to in Japanese as Chōka, was a Chinese priest in the late Tang dynasty (618–907) and was said to meditate in treetops. He is perhaps best known for his exchanges with the Chinese poet Bai Juyi (772–846). Although some paintings capture both figures in dialogue, this work depicts Chōka alone; it is based on the 1602 Ming publication Marvelous Traces of Immortals and Buddhas (Chinese: Xianfo qizong). Sōtatsu is believed to have studied the ink-painting methods of the thirteenth-century Chinese monk-painter Muqi (1210?–1269?). His own compositional skill, combined with his mastery of Muqi’s approach to ink work, animates the otherwise drab book illustration in Marvelous Traces of Immortals and Buddhas. The Tawaraya studio obtained a copy of Marvelous Traces of Immortals and Buddhas soon after it was issued and produced a large number of ink paintings based upon the book’s illustrations. The Cleveland work ranks as one of the most accomplished.

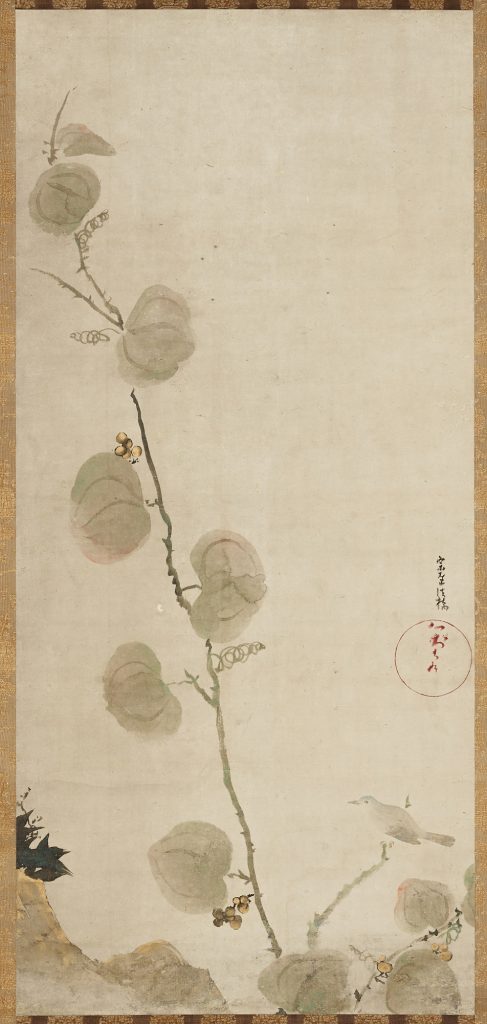

Sankirai

This delicately rendered plant, balanced with a small bird and bamboo grass, is called sankirai(“mountain plucked”; Smilax china). It is a deciduous, thorny climbing plant that grows by attaching itself to other plants. Its red fruit acts as a detoxicant and is a kind of sarsaparilla. The characters for its Japanese name indicate that it was sought in mountains because of the medicinal effects of its fruit and root.

This painting is a fine example of Sōtatsu’s close observations of nature and penchant for elevating the obscure distinction with elegant technique. It was formerly in the collection of Kawai Gyokudō (1873–1957), one of Japan’s most celebrated painters working in nihonga, the twentieth-century attempt to depict traditional topics in avant-garde styles—more evidence of Sōtatsu’s influence on modern Japanese painting.

Master Poet Motokata

This painting depicts the “poetry immortal” Ariwara no Motokata, a courtier-poet active in first half of the tenth century. The figure manifests Sōtatsu’s distinctive and graceful style, in which each line begins with little inflection at its head, thickens in the middle, and thins out in the end. The composition is based upon the tradition of depicting Motokata in paintings associated with “Poetry Match of Poems from Different Eras” (Jidai fudō uta-awase), an imaginary competition among poets from different time periods. The earliest-known illustrated versions appeared in the Kamakura period (1185–1333). It is clear from minute details that Sōtatsu was working from a medieval version. But compared to Kamakura period examples, his poet portraits have longer, fuller faces, with less severe expressions and a gentle air. The softening of earlier ink-painting styles was one of his characteristics.

Dragon and Tiger

These two scrolls were originally part of a set of twelve paintings pasted onto a pair of six-panel folding screens. They work effectively as a pair, because dragons and tigers have been coupled as painting subjects in Japan since ancient times. This composition pits them glaring at each other—a heavenly dragon looking upward and the earthbound tiger downward. The dragon is stylistically similar to the much larger versions seen in the Dragons and Clouds screens (displayed nearby), where the same bulging eyes and use of tarashikomisuggest a recognizable Sōtatsu style.

Although there is no signature, both scrolls are pressed with the round vermilion relief seal I’nen, which was used by the Tawaraya atelier. Dragon and Tiger thus is usually understood to be a studio production. Its exceptional quality makes it difficult to say whether it is by an outstanding disciple who mastered the Sōtatsu style or by the master himself.

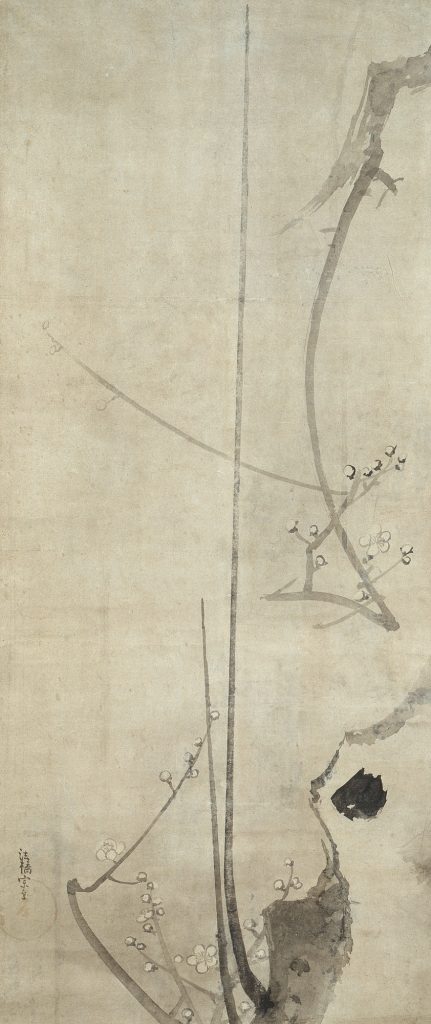

Plum Tree

This painting shows that Sōtatsu carefully researched Chinese models, whether they were original paintings he saw in and around Kyoto or illustrations in woodblock-printed books. Prototypes for this composition include a more realistically depicted plum-tree painting attributed to the monk-painter Minchō (1352–1431) and plum-tree paintings by Song dynasty artist Yang Wujiu (1097–1169).

Plum Tree documents Sōtatsu’s interest in radical simplification and seeing the underlying essence of forms. If it lacked blossoms, the plum branch would be a bold exercise in abstraction. The work bears the signature Hokkyō Sōtatsu and the round vermilion relief seal Taisei.

Shamo Chicken

This scroll depicts a shamo chicken (game fowl) with a confident pose. It was done entirely in monochrome ink, except for the touches of red in the crown, wattle, and earlobe. The round vermilion seal I’nen is pressed in the lower left corner. Evidence of damage at the top portion of painting may indicate it was once a panel element pasted on a folding screen.

Various examples of this fowl appear in early to mid-seventeenth-century paintings , some with the I’nen seal and others, rendered more flatly, bearing the Taiseken seal. The former type is considered to be older. The shamochicken did not appear as a single subject in Japanese painting prior to Sōtatsu’s time, although it was depicted in early narrative scrolls. Sōtatsu’s deep research into medieval painting scrolls may have elevated this tiny and miscellaneous subject to a new prominence.

A Child Holding a Spotted Puppy

The boy in this painting appears to be Chinese, placing the work within the East Asian painting tradition known as “Chinese children playing” (karako–asobi). Even when Sōtatsu had a model, however, his reinterpretation of the subject was a hallmark of his artistry. With a soft, relaxed line that is not apparent in Chinese painting and his modest and effective use of the tarashikomi technique, Sōtatsu overturned the standards that had been associated with Japanese ink painting since the Muromachi period (1392–1573) to depict a tranquil, endearing everyday scene. The bluish tint of the silk seems to be original and suggests some experimentation by Sōtatsu or his studio.

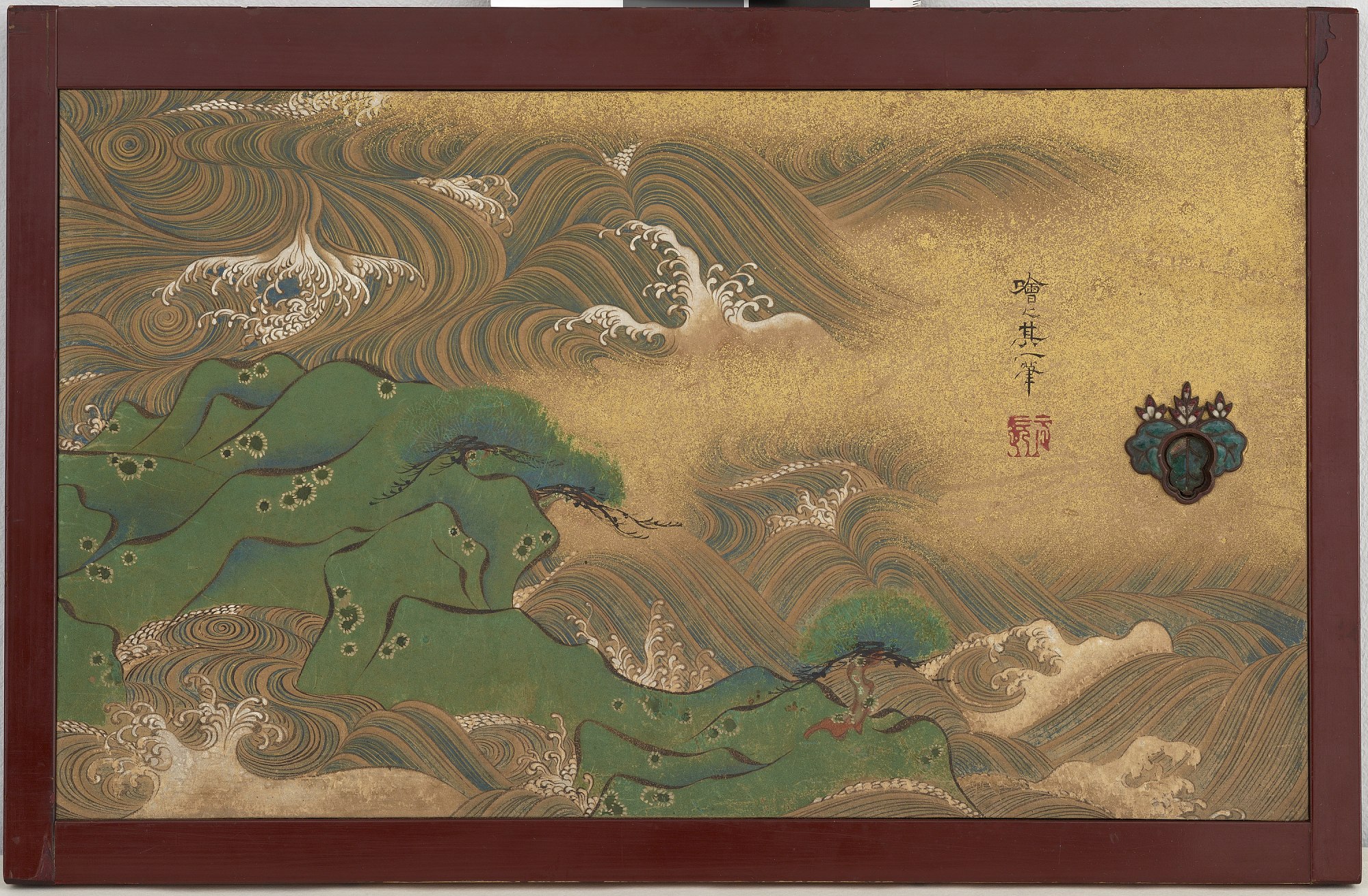

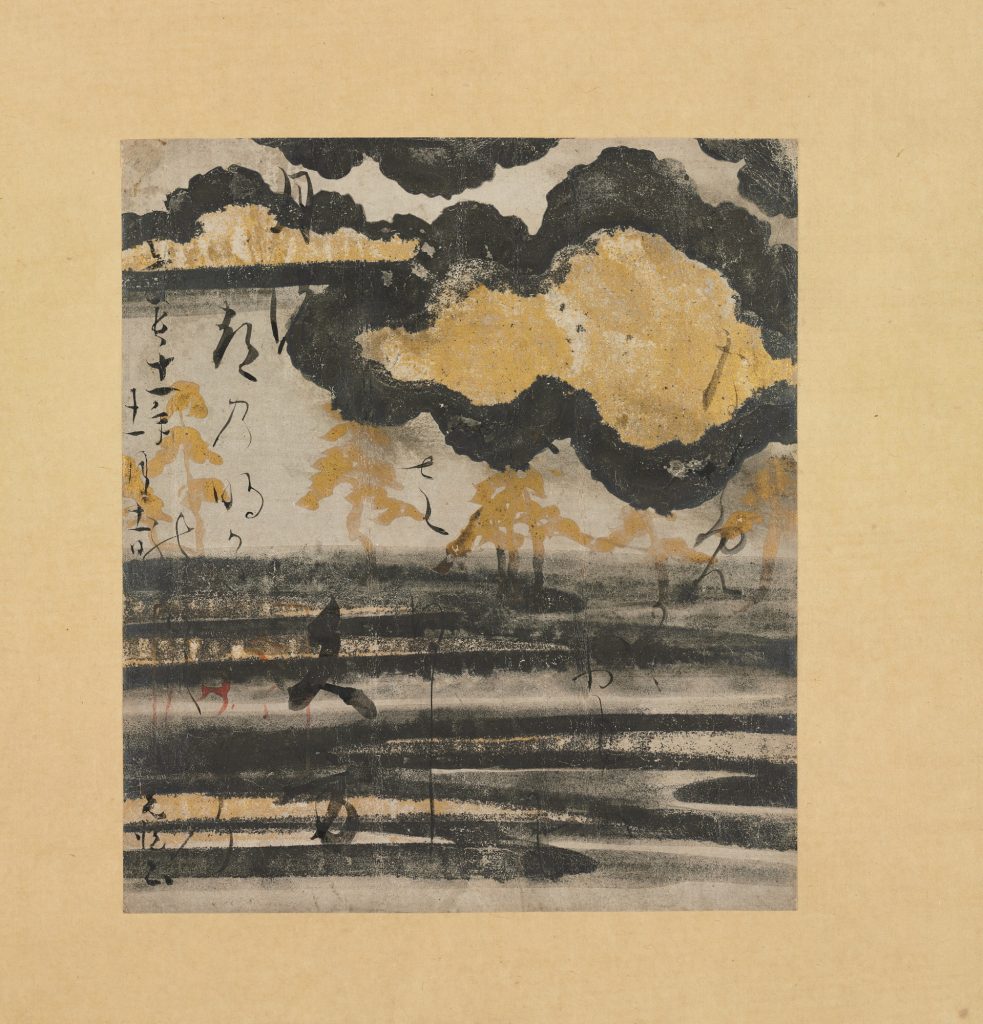

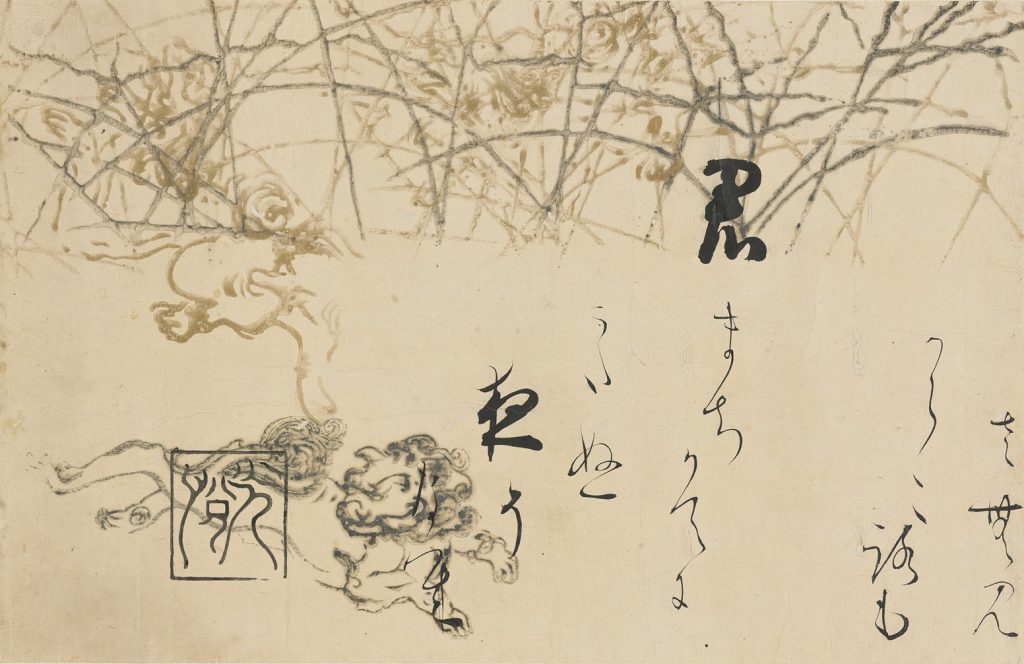

Dragons and Clouds

These paired dragons in clouds are tour-de-force representations of Sōtatsu’s highly transformative and original ink-painting style. With Waves at Matsushima, they rank as Sōtatsu masterpieces. They were acquired by Charles Lang Freer in 1905, one year before he purchased the Waves;the source was the same—dealer Kobayashi Bunshichi (1861–1923)—but the provenance of Dragons is unknown.

The standard iconography shows an ascending dragon, rising to the heavens in spring, with a descending dragon, returning to the abyss in autumn. Their movements were associated with the seasonal cycle and the abundance of the natural world. Here, the right screen depicts a descending dragon while the left screen depicts its ascending counterpart. This alignment unusually places the signatures and seals on the inside corners. Changing the left-right order, however, would eliminate the compositional tension of the two dragons glaring at each other.

Some scholars suggest that Sōtatsu derived the idea for at least the right screen from one in Honpōuji, the Hon’ami family’s mortuary temple in Kyoto. It is possible that Sōtatsu was able to study the screen through an introduction facilitated by calligrapher Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637). It is difficult to place these screens within Sōtatsu’s chronology of production. According to one theory, hints of The Gods of Wind and Thunder, another Sōtatsu masterpiece, can be seen in these dragons. Yet another perspective states that the Dragons may have inspired Waves at Matsushima. Sōtatsu clearly was interested in cosmology and the sources of water and fertility, as those themes are displayed in his most important works.

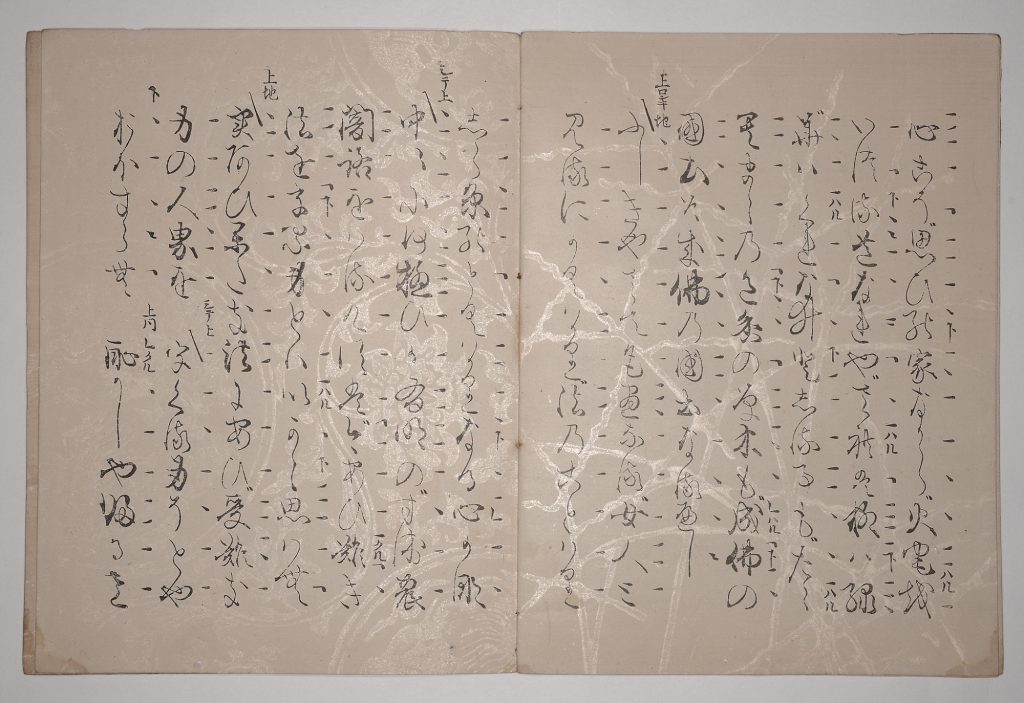

Classicism

Sōtatsu lived in an era of profound social change. The warrior class led by the shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) and his descendants assumed political power in the early seventeenth century and, for the first time, permitted the spread of previously privileged knowledge. Classical literature and its interpretations and visual representations, once restricted to the aristocracy, gradually became available to a wider audience. Ancient narratives, such as Tales of Ise and Tale of Genji, were codified, and a standardized set of images—depicting key moments in the narrative plots—created a common pool for the public imagination. Sōtatsu was a singular force in devising those canonical images, and his folding fans served as portable image quotations from the past. Assertions of sophistication and learning but separated from their contexts, these snippets floated across many social boundaries. Association with a deep cultural past, even in fragments, was important to ambitious members of the new social order.

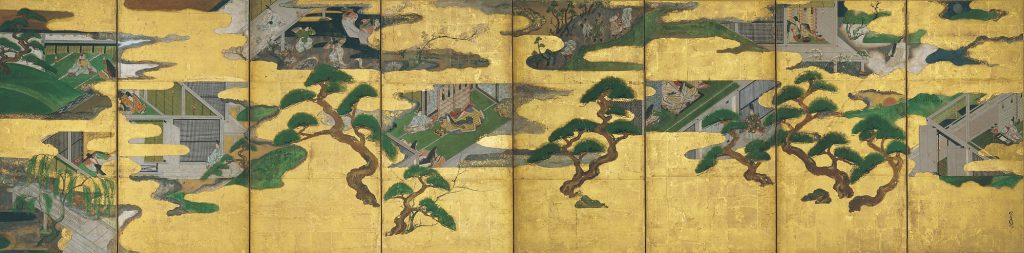

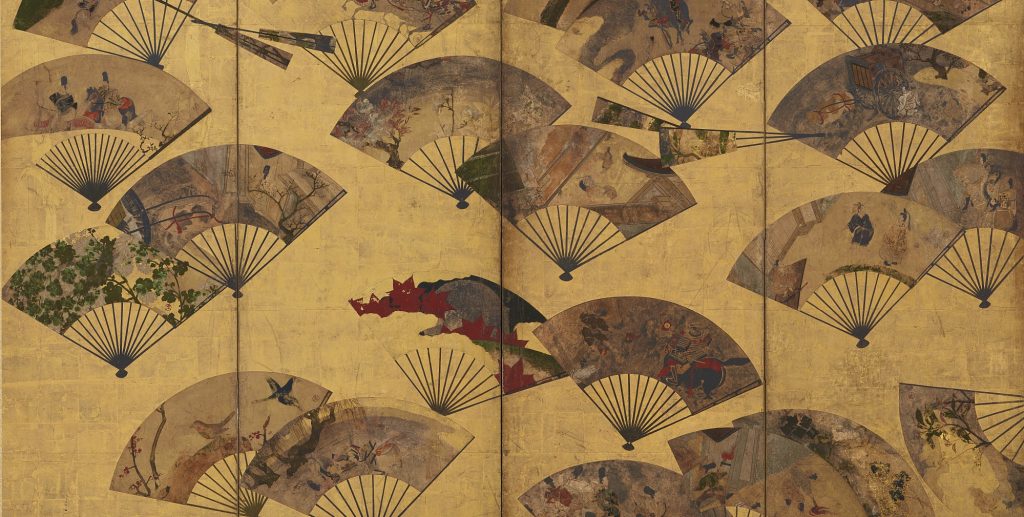

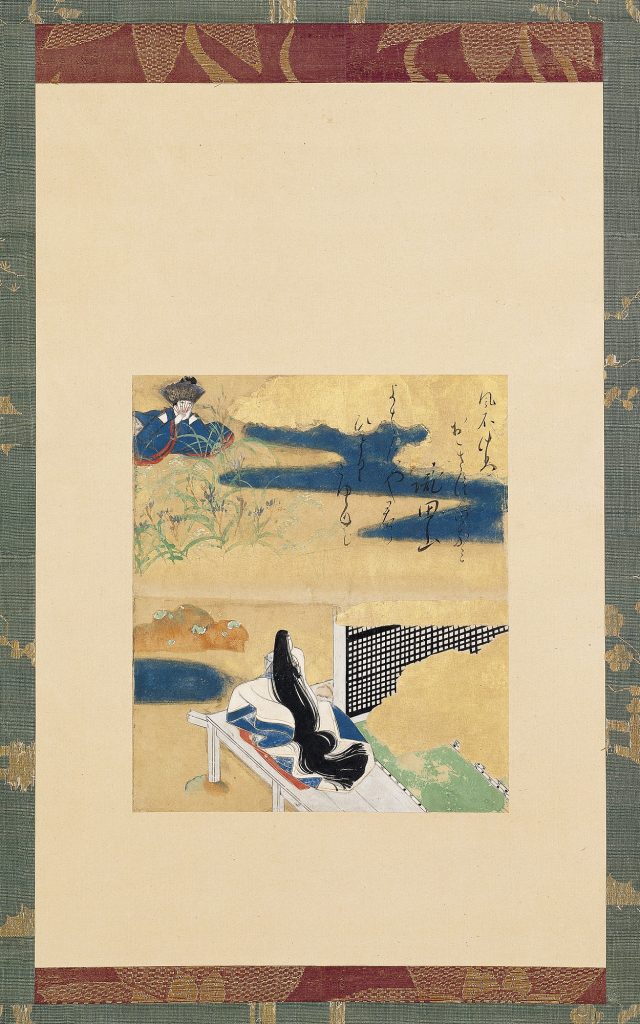

Painted Fans Mounted on a Screen

This work showcases the artistry of Sōtatsu and the Tawaraya studio through one of their most prominent genres, the “floating fans” screen. An indisputable chain of provenance shows that the screens have been in Japan’s imperial collection since they were made in the 1620s. They are the most prominent of a group of screens featuring fans—all associated with the Tawaraya studio and Tōshichirō, one of Sōtatsu’s talented disciples.

There are three fans per panel, for a total of forty-eight. Most of the fans represent scenes from the military epics Tales of Hōgen and Tales of Heiji; others depict scenes from the courtly classic Tales of Ise or birds and flowers. Based on style and subject matter, the fans appear to have been painted at the same time, and the paper seams indicate that one of them was actually used as a folding fan.

A conservation project revealed that document fragments were inserted within the screens; they suggest a high-ranking patron as early as 1619 but certainly in the 1620s. Some layers of the gauze silk borders are original, and the purple border with chrysanthemum designs indicates high aristocratic patronage. The inscription “Tawaraya Tōshichirō” was found on the reverse of one fan, one of eighteen bearing the seal Tatō, thus linking the seal to Tōshichirō. Clearly, he was a painter with enough status to use his own seal. Several fans have versions of the I’nen seal, suggesting other participants and perhaps Sōtatsu himself. Tōshichirō’s works all had a military theme, which may mean he specialized in epics and in figural painting.

Ivy Vines, Bridges, and Floating Fans