“[Hindustan] is a strange country. Compared to ours, it is another world…” —Babur*

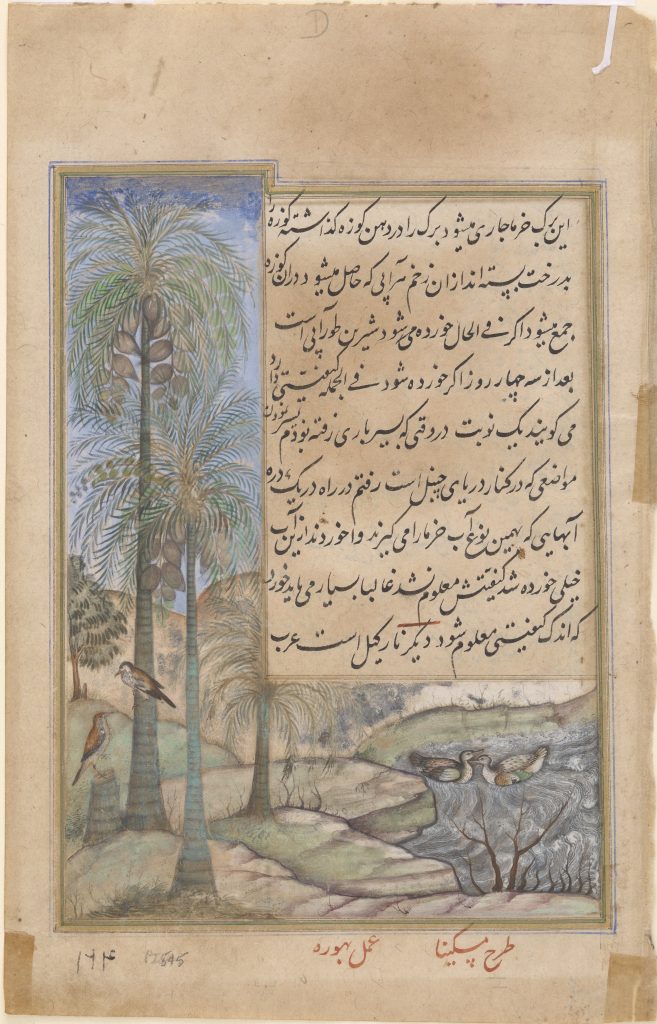

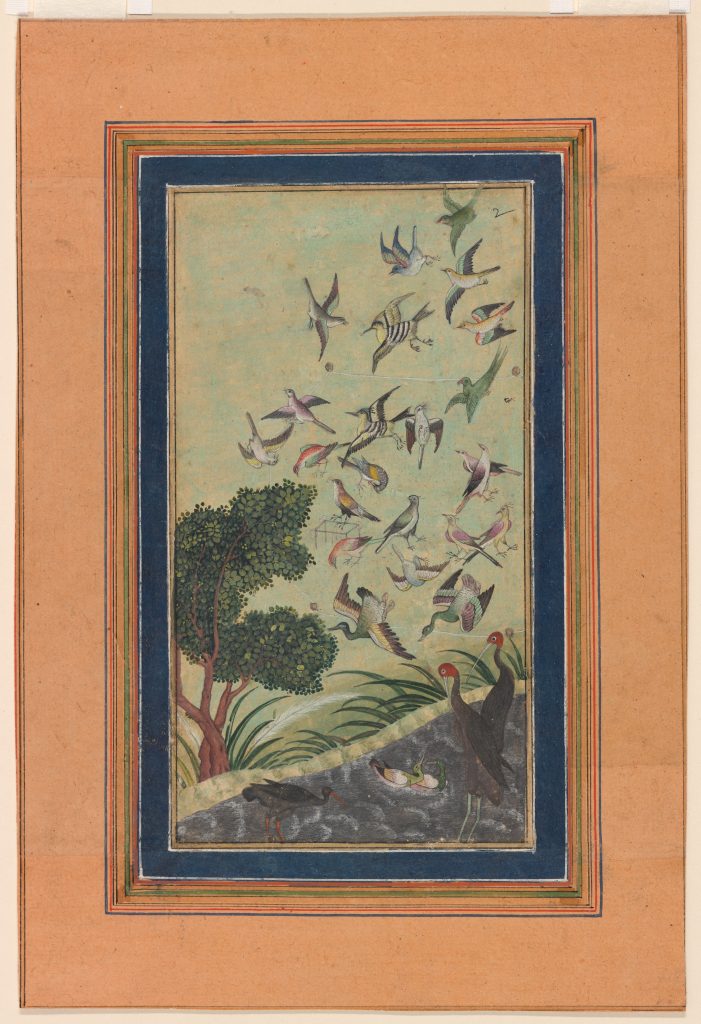

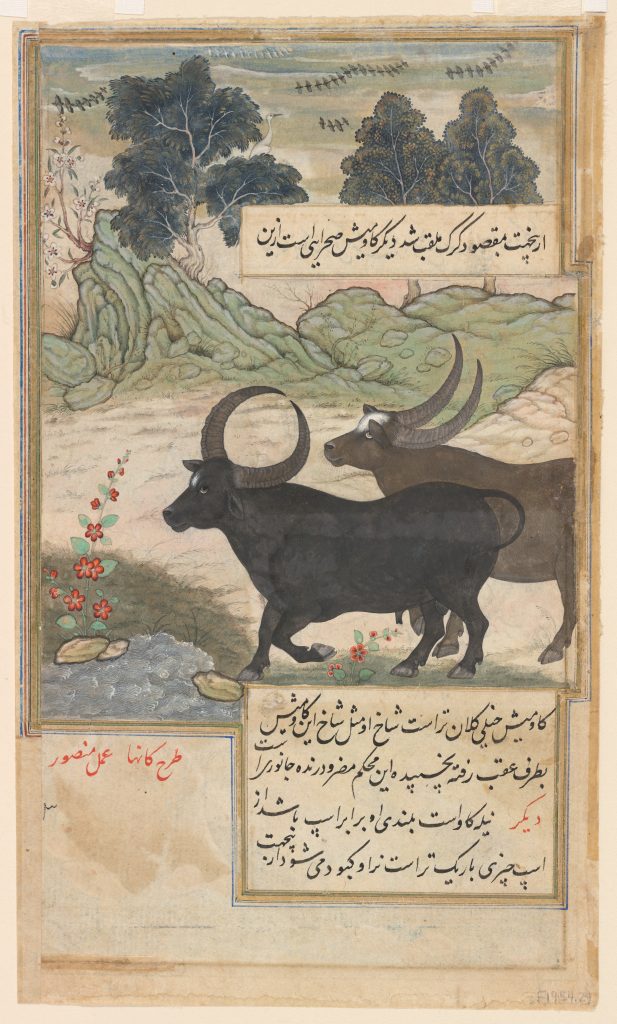

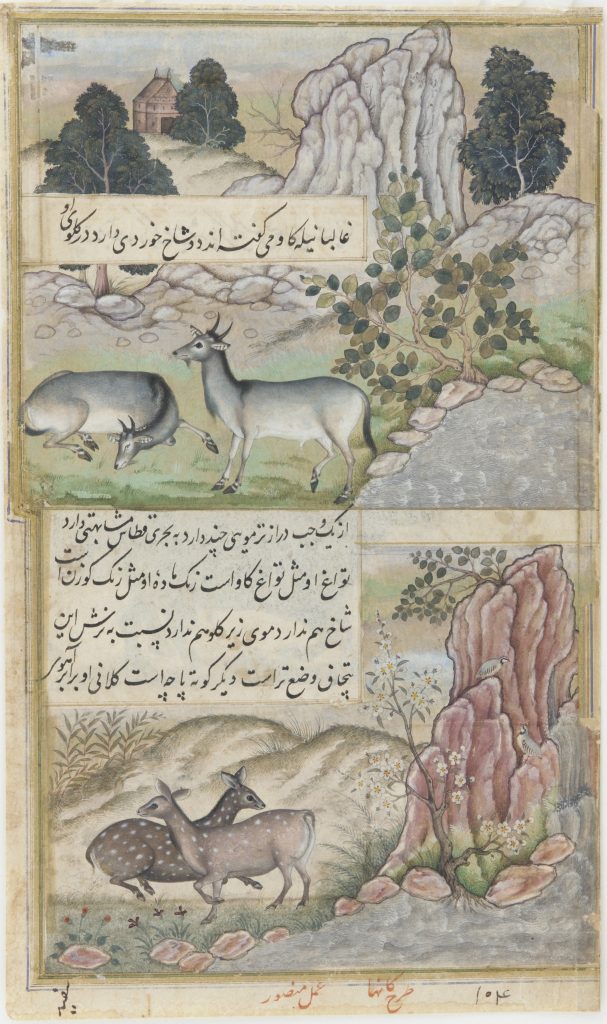

The Indian subcontinent teemed with plants and animals unknown to Babur and his Central Asian companions. After arriving in India in 1526, Babur wrote a remarkable account of the flora and fauna he encountered in his new territory. With his characteristic precision, he records the habitats, behaviors, and even flavors of these unfamiliar species.

Some eighty years later, the Mughal emperor Akbar had his grandfather Babur’s memoirs translated into Persian and illustrated. These folios are from the first Baburnama of five. Made for Akbar himself, the first Baburnama was a collaborative effort among many of the most prominent artists in the imperial workshop. Mansur, one of the greatest Mughal natural history painters, cut his teeth painting superbly observed animals on the folio you will see here . Other artists, like Farrukh Beg—whose three more stylized paintings you can also see in this exhibition—were recent arrivals to India.

*Thackston, Wheeler M., trans. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Oxford University Press in association with Smithsonian Institution, Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 1996. 332.