Ongoing

-

Dates

-

Location

Online

-

Collection Area

South Asian & Himalayan Art, Southeast Asian Art

The Divine Feminine in South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Himalayan Art

It is often said that knowledge is power. For the goddesses of South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Himalayas, power is closely connected to a particular type of divine wisdom or a state of omniscience, of knowing all things. The wisdom of the divine feminine takes myriad forms in these regions, ranging from healing to artistic skill, and from prosperity to enlightenment. Wisdom of the Goddess highlights nine well-known goddesses of Hindu and Buddhist traditions through twenty-five artworks dating from the ninth through the nineteenth centuries, all drawn from the National Museum of Asian Art’s permanent collections. Many of these representations of goddesses were used by individuals or in temple settings as aids for worship. Some were encountered in manuscripts or worn as necklaces. For devotees past and present, a goddess’s image facilitates a sense of intimate devotion and closeness to the deity.

This online exhibition includes an introduction to each goddess, detailed descriptions of individual artworks, a glossary, learning resources, and an instructional essay designed for college students and lifelong learners. Wisdom of the Goddess aims to enhance understanding of goddess imagery and the religious practices of goddess devotees globally, both in their countries of origin and throughout the diaspora.

The Goddesses

Drawn from the National Museum of Asian Art’s collections, the works in this exhibition—made between the ninth and nineteenth centuries—depict goddesses and divine female practitioners from Hindu and Buddhist traditions in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Himalayas.

-

Durga

Hindu Warrior Goddess Who Killed the Demon Mahisha; she is often seen as a form of all-knowing Great Goddess (Mahadevi).

-

Forms of Kali

Fierce Hindu goddess who eradicates demonic forces on the battlefield; she is often seen as a form of the all-knowing Great Goddess (Mahadevi).

-

Lakshmi

Hindu Goddess of Prosperity and Good Fortune; her wisdom creates abundance.

-

Parvati/Uma

Hindu Goddess of the Mountain, also known as Uma; she is often seen as the feminine half of the god Shiva, and the divine feminine power of the universe (shakti).

-

Prajnaparamita

Buddhist goddess who personifies the perfect wisdom necessary for the attainment of enlightenment.

-

Radha

Hindu Goddess of Divine Love; thoroughly understands the divine nature of the god Krishna. Hindus often view her as the feminine half of Krishna, the all-knowing, divine power of the universe.

-

Saraswati

Hindu Goddess of the Arts and Learning.

-

Tara

Bodhisattva-goddess of great compassion who aids beings in peril.

-

Yoginis and Dakinis

Yogic practitioners, often fearsome, who reveal secret teachings; they gain superhuman powers through tantric yoga.

Durga, Goddess Who Slays the Buffalo Demon

The fifth-century Hindu text Devi Mahatmya relates the well-known narrative of Durga’s triumph over evil. Though each of the gods tried, they could not defeat the earth-threatening demon Mahisha, who disguised himself as a water buffalo. Together the gods created Durga, furnishing the goddess with a bevy of weapons to use against him. Artists typically depict Durga at the moment she handily defeats the demon, seated or standing atop her lion with multiple arms fanned out, brandishing the weapons. Durga’s tale expresses the superiority of the Great Goddess (Mahadevi) over all the male gods. For her devotees, Mahadevi is the cosmic creator and the foremost divine power of the universe (Shakti). While other goddesses, including Kali or Lakshmi, can represent Mahadevi on earth, she often takes the form of victorious Durga, whose wisdom on the cosmic battlefield is absolute.

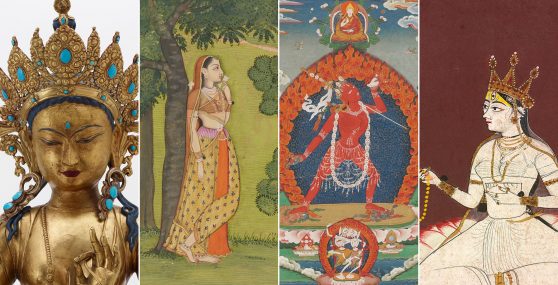

Fit for a Queen

A crowned goddess sits in a palace on a golden throne. Her stoic face is rendered in profile, the preferred mode for representing human rulers. As a form of the Great Goddess (Mahadevi), Durga holds weapons that indicate her wisdom in battle. The artist positions her higher than the other deities, a youthful Krishna at left and Vishnu and Lakshmi at right, emphasizing the central subject’s universal eminence. The goddess’s tiger mount lies on the marble ledge with a green Garuda, Vishnu’s eagle mount, perched nearby.

Image 1 of 4

Divine Fury

With eighteen arms and a flurry of weapons, Durga swiftly defeats the demon Mahisha while her expression remains serene. Although only six inches tall, this sculpture displays a captivating dynamism. Both the tiny demon and the formidable goddess appear to hover over the double-lotus plinth. Durga’s left foot presses on the buffalo’s small body as she balances her weight on the lion. She grasps the emerging demon’s hair as her lion happily gnaws Mahisha’s foot.

Image 2 of 4

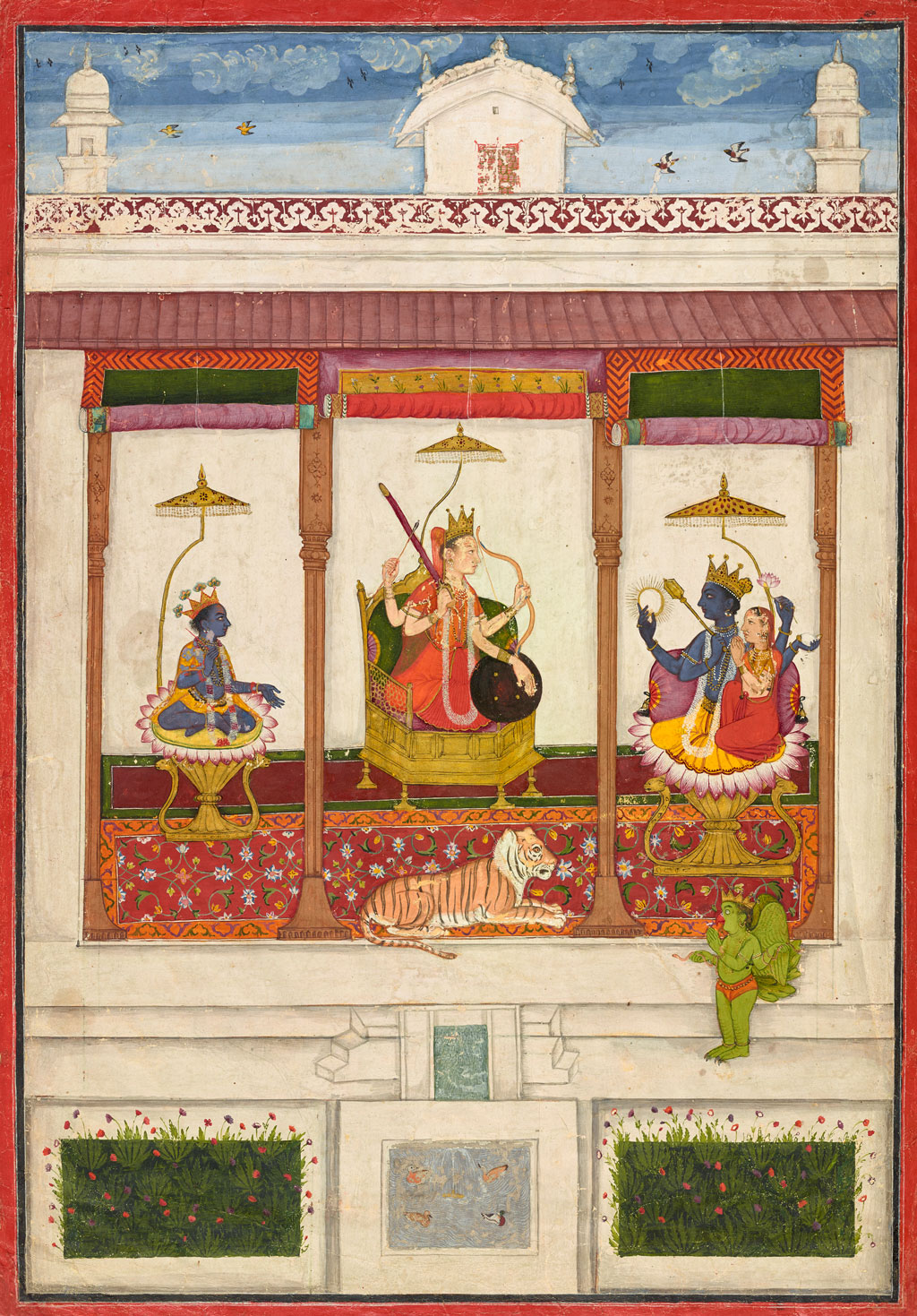

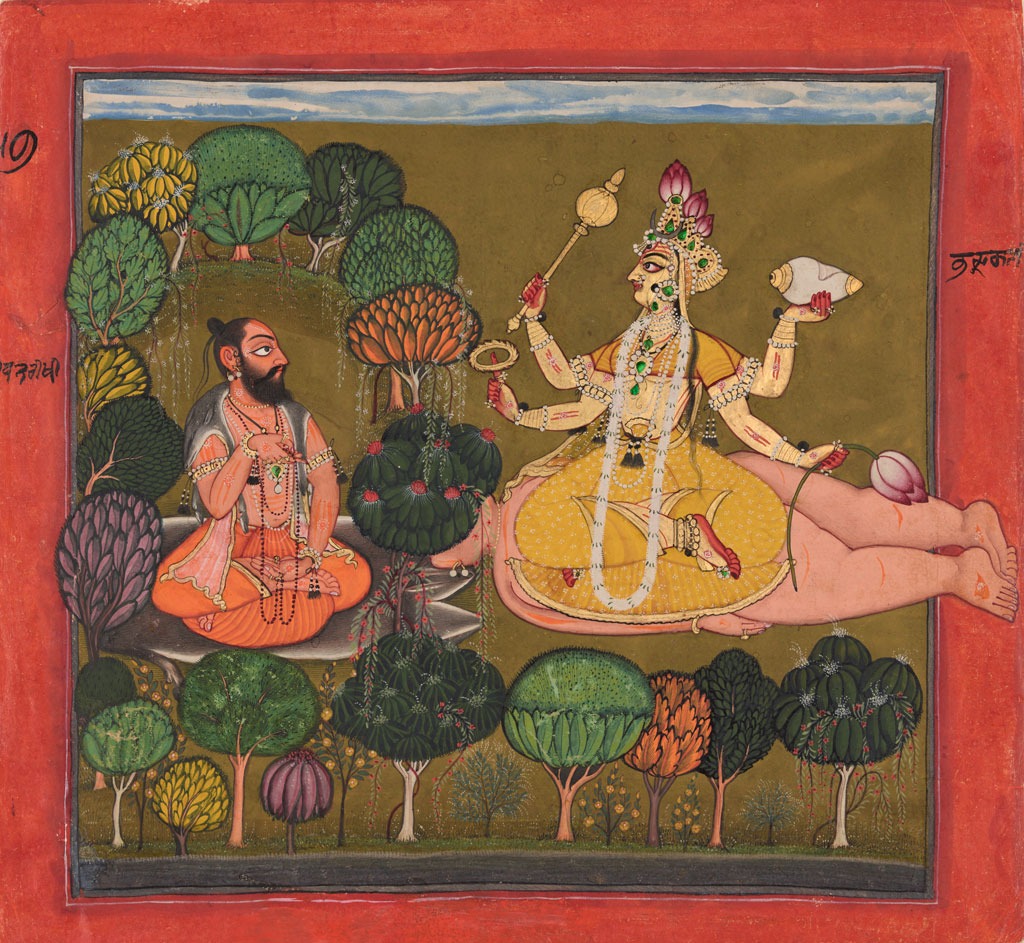

Paying Homage

The Hindu goddess Durga appears alive and present inside a domed shrine while a nobleman stands in worship before her. The brilliant marble architecture, the ruler’s crisp white garment, and the pale, blue-gray sky emphasize the bright hues of the goddess, who slays the buffalo demon from atop her lion. This painting likely depicts Thakur Ajit Singh (r. 1800–1856), who presided over Ghanerao, a village in Rajasthan state in northwestern India. Historically, Hindu kings worshiped Durga for success in battle.

Image 3 of 4

Triumph over Evil

By the time Javanese sculptors carved this exquisite sculpture in the ninth century, the worship of deities central to Hindu traditions had spread from India to Southeast Asia. Here, rather than depicting Durga’s many implements, the artist focuses instead on her elegantly adorned form. The goddess stands triumphantly on the back of the water buffalo demon, her dynamic posture emanating authority. She pulls the buffalo’s tail tightly with her lasso while grasping the demon’s human-like head.

Image 4 of 4

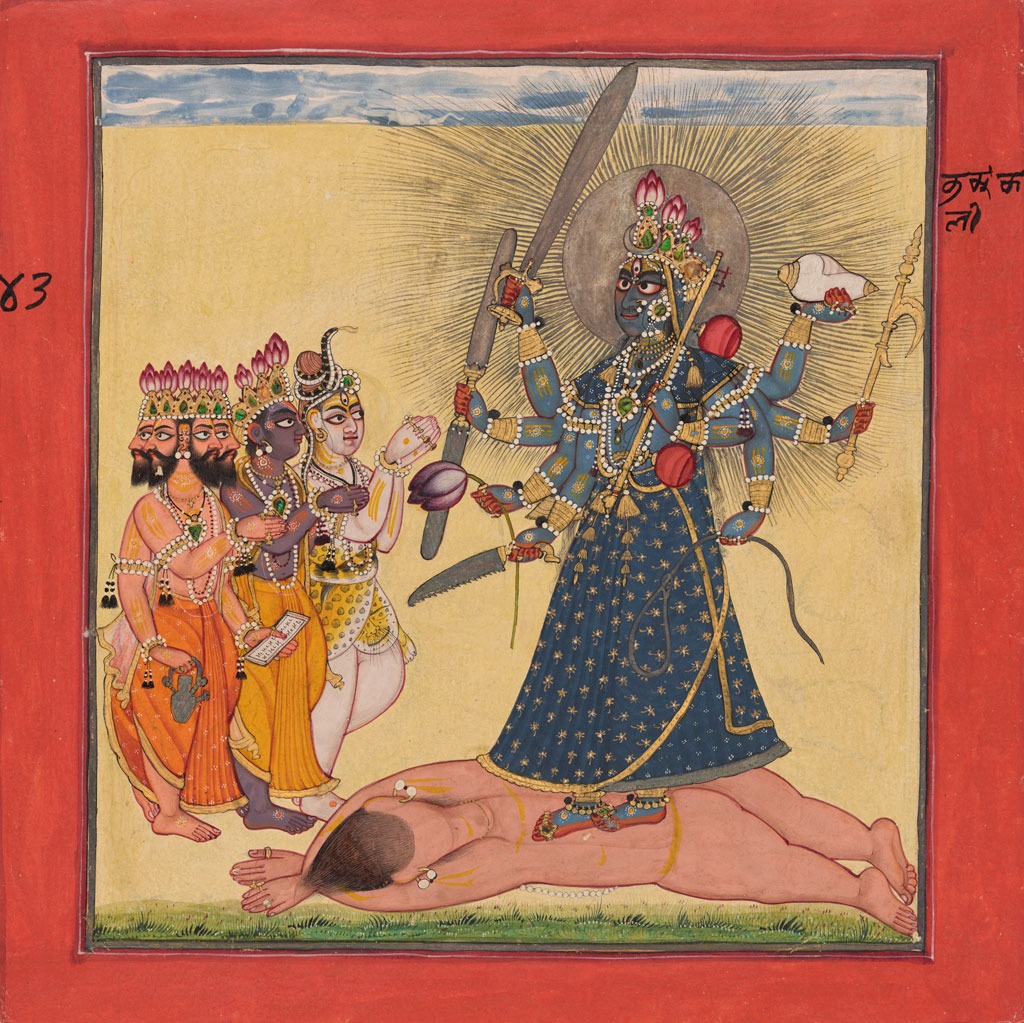

Forms of Kali, Mother and Destroyer

The goddess Kali destroys all forms of evil, including delusions that obscure the wisdom of moksha, or liberation from our world of samsara, in which the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth is endless. Hindus worship Kali as the Great Goddess (Mahadevi) and mother of the universe. A popular narrative describes Kali—tongue lolling, wearing a garland of skulls and a skirt of human forearms—engaged in a demon-killing spree on a cosmic battlefield (see related image). So intense was her rage that her husband, the god Shiva, laid down in her path to prevent her from unwittingly destroying the universe. This legend likely reflects Kali’s beginnings as a local deity whose appeasement prevented unwanted destruction. Although she is considered primarily benevolent in present-day culture, Kali—also known as Bhadrakali—retains a sense of unpredictability. As devotee-poet Ramprasad writes: “Who knows what she truly Is? . . . If She decides to be kind, this misery will pass.”1

1 Ramprasad Sen, translated by Leonard Nathan and Clinton Seely, Grace and Mercy in Her Wild Hair (Prescott, Hohm Press, 1999), 32.

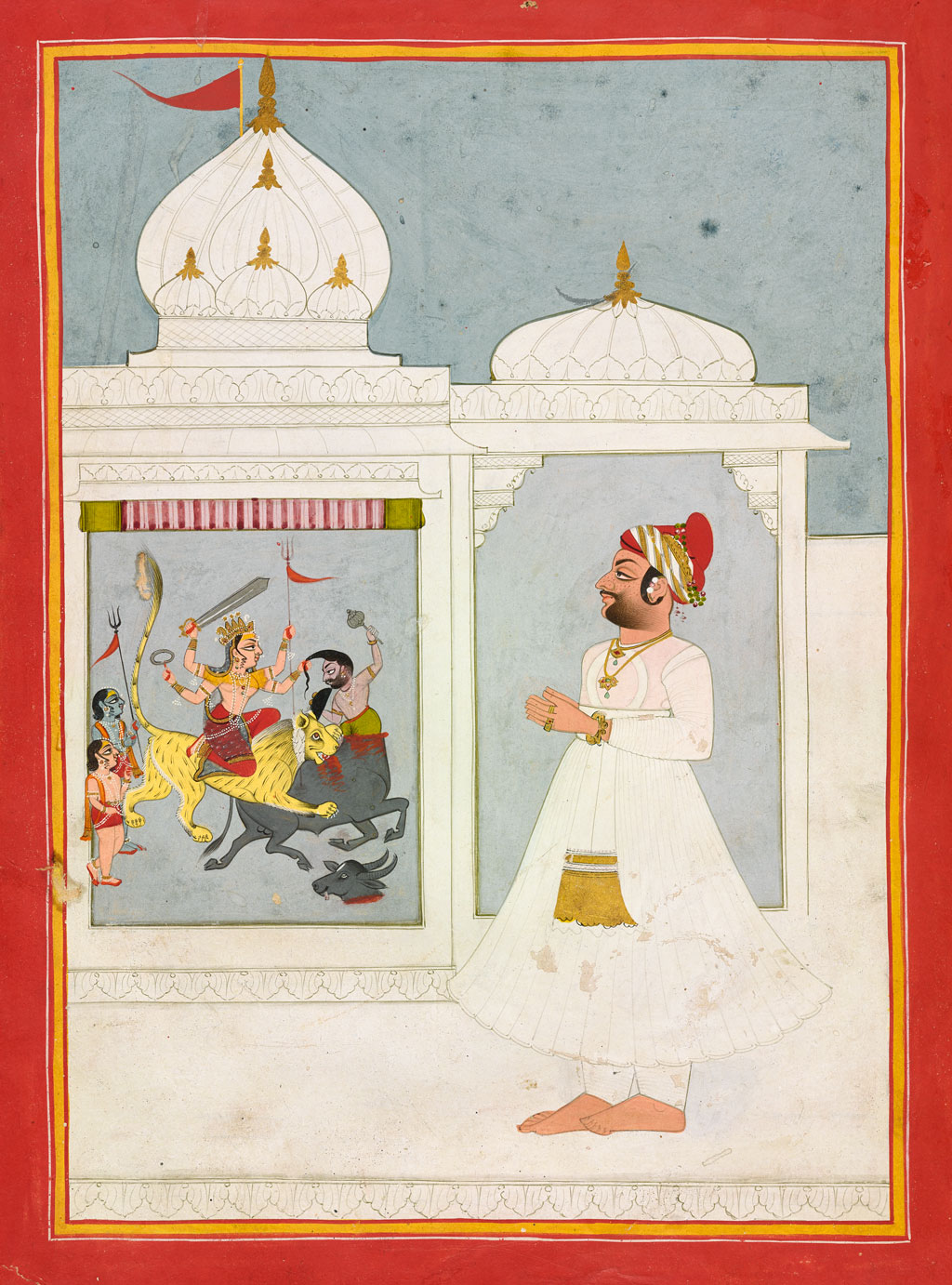

An Important Message

The Hindu goddess Bhadrakali gleams among the deep, lush colors of a bursting landscape. Her body is radiant with the application of gold, her glimmering jewels the emerald of beetle wings. She sits on a large human corpse, the scene a representation of her triumph over death. Appearing before the sage Chyavana, she holds the god Vishnu’s four implements, signaling that the sage, who worships Vishnu, would be wise to know her as the supreme goddess of the universe.

Image 1 of 3

Catching Rays

This painting reverberates with divine feminine power (Shakti). The artist has skillfully applied vibrant pigments and reflective silver. Bhadrakali’s upraised sword catches the emanating light of her silver halo. Known as “Auspicious Kali,” here the goddess is superior to all other deities. The three greatest Hindu gods, Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, pay homage to her. She stands upon a prostrate human form symbolizing death, holding weapons that dispel illusion and signal her ultimate wisdom.

Image 2 of 3

Above All

With deeply saturated colors and linear precision, the artist depicts a Hindu form of the Buddhist goddess Tara cross-legged atop the prone body of the god Shiva. She holds potent implements, her skin a smoky hue. In Hindu tantric traditions, Tara is a close counterpart of Kali and one of ten goddesses of great ritual knowledge (Mahavidya) who personify divine feminine power (Shakti). Without the power of these goddesses, the gods cannot act. Embodying aspects of Shiva's fierce wisdom, Tara demonstrates this dominance.

Image 3 of 3

Lakshmi, Goddess of Prosperity

Lakshmi, also known as Shri, possesses divine wisdom that creates abundance. She offers her devotees great wealth. Since the first century BCE, artists have depicted the goddess holding lotuses, symbols of purity and divine power, together with elephants spraying water from their trunks. At right, a chromolithograph by Raja Ravi Varma takes inspiration from this classical mode. The distribution of such chromolithographs throughout India in the early twentieth century increased the popularity of certain deities and solidified specific ways of representing them. Varma depicts Lakshmi flanked by an elephant representing good fortune. Lakshmi stands on a lotus that floats on refreshing, cleansing water. This collective symbolism indicates that the goddess’s blessings surpass monetary gain alone. Both Hindu and Buddhist texts describe her as creating verdant lands that yield abundant harvests. Lakshmi is commonly known today as the wife of the Hindu god Vishnu.

Temple in Miniature (full artwork)

The Hindu god Vishnu stands below a trefoil arch, flanked by his much smaller divine wives. The goddesses—Lakshmi at left, Saraswati at right—lean inward, creating a pleasing triangular formation with the god’s towering, crown-topped form. The earth goddess (Bhudevi) is typically depicted as Vishnu's co-wife along with Lakshmi, but in Odisha, India, where this shrine was made, Saraswati appears instead. Open latticework lightens the weight of the tower (shikhara) above, which resembles the regional temple architecture of this period.

Image 1 of 5

A Wealth of Detail (detail)

While diminutive in stature relative to her husband, the Hindu god Vishnu, who stands at center, Lakshmi radiates with divine energy. The goddess’s outstretched hand offers endless abundance. Her garment’s fluid folds cling to her body, while her three-bend, standing posture lends a sense of movement and graceful ease. Her round face and ornate side bun counterbalance a lush lotus that nearly grazes her cheek.

Image 2 of 5

Gold Rush

The central pendant of this Hindu marriage necklace (thali) depicts the goddess of abundance, Lakshmi. In colorful calendar prints made in India today, Lakshmi pours gold coins from her upraised hand to signify prosperity. Sculpted in twenty-carat gold, this representation of Lakshmi embodies wealth. Composed of intricately designed pieces strung with cord, the necklace weighs over two pounds. Its large, spiked pendants evoke the spray of palm fronds traditionally placed around a bride’s neck after the wedding couple exchanges vows.

Image 3 of 5

Goddess in Gold (detail)

Lakshmi possesses the divine power and know-how to grant her devotees great prosperity. At the center of this exquisite Hindu marriage necklace (thali), the goddess’s repoussé image was created by hammering sheets of metal on the reverse side. She raises her left hand in the gesture that removes fear, while her open palm signifies abundance and great wealth. The patrons of such heavy gold necklaces with spiky protrusions are often members of the Chettiar community of wealthy merchants in South India. (View the full necklace online)

Image 4 of 5

Powerful Goddess/Demure Devotee (detail)

In this detail, Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of abundance, is rather incognito. Seated on her husband Vishnu’s lap, she is bejeweled yet unassuming. Vishnu, whose dark blue skin emphasizes his divinity, wears a crown, while Lakshmi’s head is more humbly adorned with a finely woven translucent red scarf (orhni). Lakshmi presses her hands together in a gesture of homage while staring intently at the Great Goddess (Mahadevi) at the center of the composition. (View the full painting in the exhibition section on the goddess Durga)

Image 5 of 5

Parvati/Uma, Goddess of the Mountain

The Puranas, literally the “old stories” of Hindu traditions, relate the narrative of the goddess Parvati, who aspired to marry the god Shiva. Because Shiva could not easily be distracted from his yogic meditation, Parvati subjected herself to extreme acts of physical deprivation—such as meditating in cold water during the winter—to gain supernatural powers and win over the celibate god. Parvati’s yoga was incredibly successful. Describing her as “full of wisdom,” the Vamana Purana states: “When the gods gathered to see the mountain daughter, they were so overcome with her brilliance that they could not approach her” for she was “outshining” the highest among them.2 Some devotees consider the goddess Durga (destroyer of the buffalo demon) to be the warrior form of Parvati/Uma.

2 Cornelia Dimmitt and J. A. B. van Buitenen, Classical Hindu Mythology: A Reader in Sanskrit Puranas (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978), 158–59.

Imagining Worship

Austere in appearance, Khmer sculptures of the Hindu goddess Uma convey regal stability. The long, ribbed skirt (sampot) creates a columnar base, while Uma’s bare chest, pinched waist, and broad hips emphasize femininity. A small bump on the sarong’s right side likely formed a strut that supported the goddess’s lowered right hand, which offered blessings or held a flower. Uma’s limbs and torso were elegantly adorned with real gold jewelry, similar to the wide belt and intricate crown carved on the sculpture.

Image 1 of 4

Royal Visage

In South India, where this sculpture was made, the Hindu goddess Parvati is known as Uma. With an idealized body, tapering limbs, tightly fitting garments, and a royal crown, Uma serves as mother, queen, and divine feminine power (Shakti) for her devotees. To honor the goddess, temple priests adorned her slender form with textiles, flowers, and real jewelry. Lugs on the sculpture’s base were fitted with poles used for carrying the well-adorned goddess in festive processions.

Image 2 of 4

Royal Visage (detail)

In South India, where this sculpture was made, the Hindu goddess Parvati is known as Uma. With an idealized body, tapering limbs, tightly fitting garments, and a royal crown, Uma serves as mother, queen, and divine feminine power (Shakti) for her devotees. To honor the goddess, temple priests adorned her slender form with textiles, flowers, and real jewelry. Lugs on the sculpture’s base were fitted with poles used for carrying the well-adorned goddess in festive processions.

Image 3 of 4

Domestic Bliss

In this scene of a close-knit family, springtime blooms in the foothills of the Himalayas. Pahari (“hill”) paintings made transcendent Hindu deities relatable, often depicting the Hindu goddess Parvati together with the divine ascetic-turned-family-man, Shiva, in endearing outdoor homemaking scenes. In this work, the two strain liquid through cheesecloth as the elephant-headed god Ganesha, here a baby, reaches for his mother’s breast. The many-headed divine toddler, Skanda, gives water to Nandi, Shiva’s bull, while his peacock and Ganesha’s bandicoot look on.

Image 4 of 4

Prajnaparamita, Goddess of Enlightened Wisdom

The goddess Prajnaparamita embodies the perfection (paramita) of wisdom (prajna) that leads to Buddhist enlightenment. Therefore, devotees refer to her as the “mother of all Buddhas.” She also represents the teachings contained within a genre of texts written in ancient India beginning around 100 BCE that describe the path to becoming a Buddha. Artists depict the goddess holding the earliest of these texts (sutras), the Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Verses. While such early Mahayana (“great vehicle”) sutras instruct practitioners to revere the texts, the goddess who personifies them did not appear in art until the sixth or seventh century. Once introduced, the goddess’s figural image became widely popular throughout the Buddhist world, including in Southeast Asia and the Himalayas. The Heart Sutra, commonly recited in Mahayana and Tibetan Buddhism today, contains her dharani, a type of long-form mantra.

By the Book

In this detail from a wooden book cover, Prajnaparamita (“Perfection of Wisdom”) sits in a verdant valley among seven Buddhist goddesses. (View the full image) Various ritual texts specify how to depict each goddess. Here, the artist focuses on carefully delineating Prajnaparamita’s elegant form and ornate, double-lotus throne. She is golden in color, her legs expertly folded in the lotus posture. In her upper right hand, she holds the oblong form of a manuscript that contains the teachings she embodies.

Image 1 of 4

Visualizing Enlightenment

Prajnaparamita personifies the Buddha’s enlightened wisdom and thus his power to teach others. With eleven towering heads, she sees and understands all. And, like the teachings (or dharma) she embodies, her twenty-two arms reach out to relieve the suffering of beings. Each of her multiple hands holds a book or other powerful object. The goddess’s swayed back, sloping hips, and long skirt (sampot) secured with a bejeweled belt balance her exuberance with a sense of restraint.

Image 2 of 4

Visualizing Enlightenment (detail)

Prajnaparamita personifies the Buddha’s enlightened wisdom and thus his power to teach others. With eleven towering heads, she sees and understands all. And, like the teachings (or dharma) she embodies, her twenty-two arms reach out to relieve the suffering of beings. Each of her multiple hands holds a book or other powerful object. The goddess’s swayed back, sloping hips, and long skirt (sampot) secured with a bejeweled belt balance her exuberance with a sense of restraint.

Image 3 of 4

A Compassionate Teacher

The goddess wears an ornate crown with ribbons flying upward. Lotuses symbolizing compassion frame her as she sits in a jaunty, royal-ease posture with one leg hanging down. But which goddess is this? Because her index fingers touch together in the Buddhist gesture (mudra) of teaching, she is likely Prajnaparamita, embodiment of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra. However, because a text does not appear atop the lotus in her left hand, this may instead be the goddess Tara.

Image 4 of 4

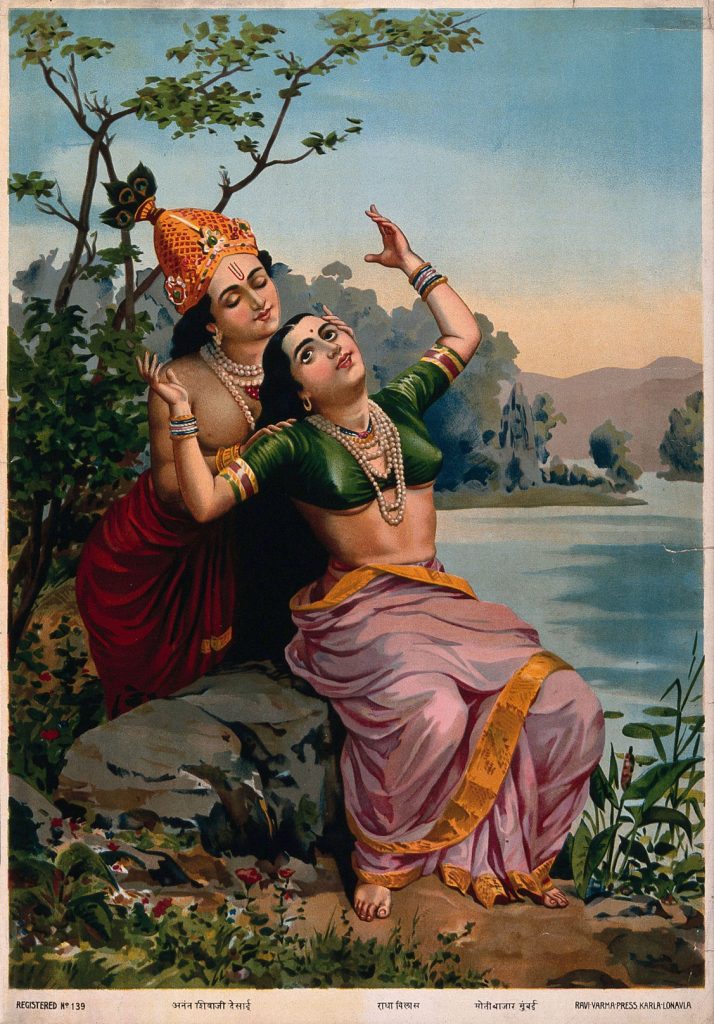

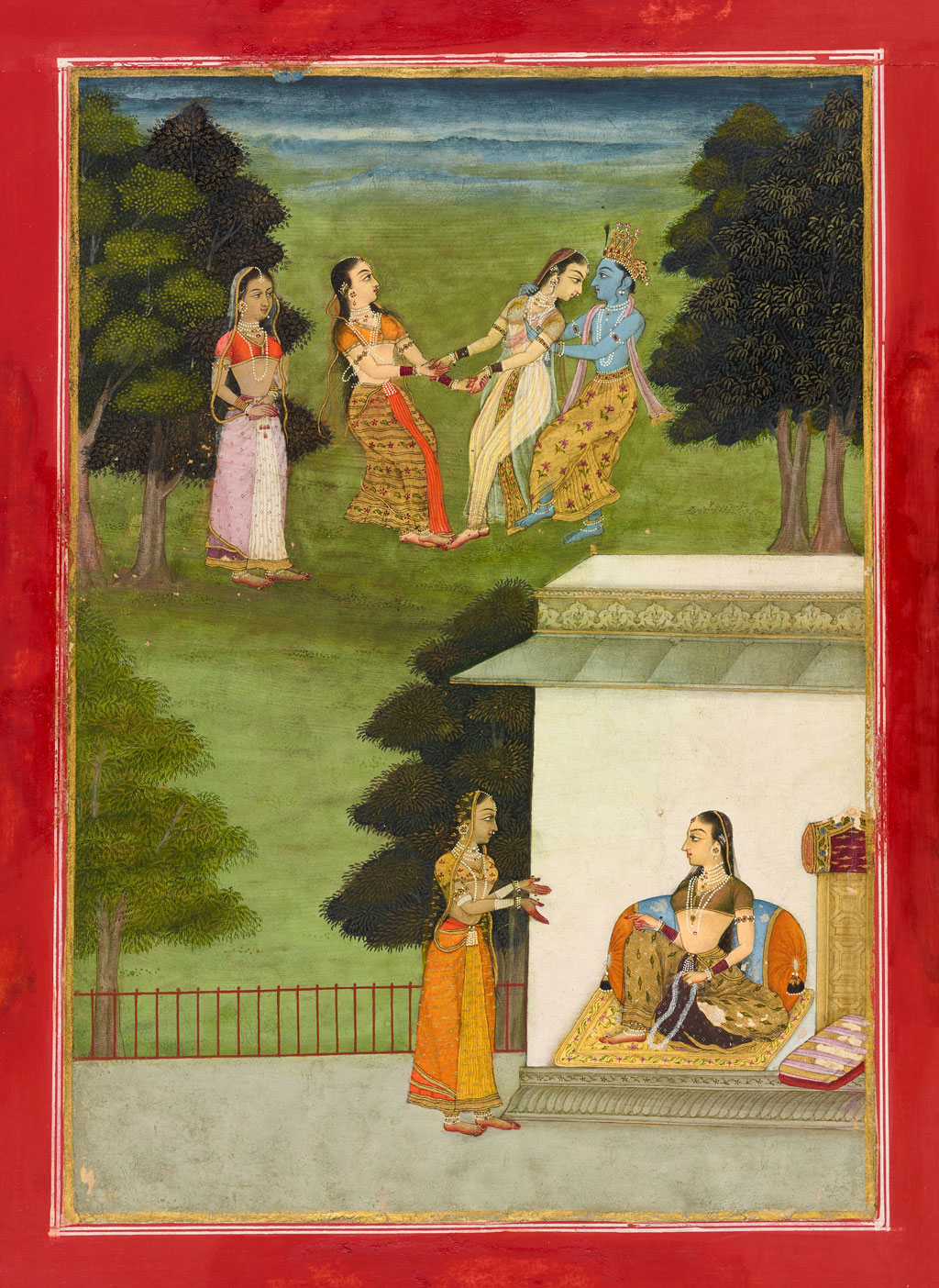

Radha, Goddess of Divine Love

Many Hindus celebrate Radha’s love for the god Krishna. A woman from a village of cowherders, Radha is worshiped today as a goddess alongside Krishna, as one of two inseparable halves of a divine being. The Bhagavata Purana (ca. tenth century) tells stories of Krishna’s life on earth in an Indian village. He was so handsome and enchanting that everyone, including one hundred gopis (female cow herders), fell in love with the young god. Sometimes Krishna playfully disappeared when he was with them, reappearing only when the gopis could love him without needing to possess him as their own, thereby relinquishing their egos. In later poetic narratives, such as the twelfth-century Gita Govinda, Radha becomes Krishna’s beloved over all others. Her love for the fleeting god is selfless, so secure is she in the knowledge that Krishna’s divine presence is transcendent and absolute.

The Day’s End

The Hindu goddess Radha’s longing for the god Krishna is often understood as a metaphor for the soul’s longing for god. Jayadeva’s twelfth-century poem, the Gita Govinda, describes the passionate yearning she feels for Krishna, and Krishna for her. Here, the artist depicts Radha, the village girl, as a beautiful princess, signaling her divine status. She awaits the arrival of her beloved Krishna as the moon begins to rise. The empty landscape suggests the pain of separation.

Image 1 of 3

Faithful Friend

Hindu goddesses have long been featured in songs and court poetry, and now television series and films. In 1591, the poet Keshavdas’s Rasikpriya transformed the Sanskrit tradition of romantic tales by identifying the typical hero and heroine as the deities Krishna and Radha. Court painters captured his verses, recounting the joys—and sorrows—of their tumultuous love. Here, Krishna frolics with multiple women. In the lower register, Radha, dressed in gold and holding a white jasmine garland, hears of Krishna’s infidelity from her girlfriend.

Image 2 of 3

Thrilling Expectation

This vibrant scene is from the Rasikpriya, a poem detailing the tumultuous love story of the Hindu god Krishna and his divine love, Radha. He is so mesmerized by the sight of her on the second-story balcony that he drops the breath-freshening betel leaves he holds, blissfully unaware that he is instead about to eat a lotus bud. Radha’s female companions look on, bemused by Krishna’s gaffe. Equally spellbound, Radha appears to mimic his gesture toward her own lips.

Image 3 of 3

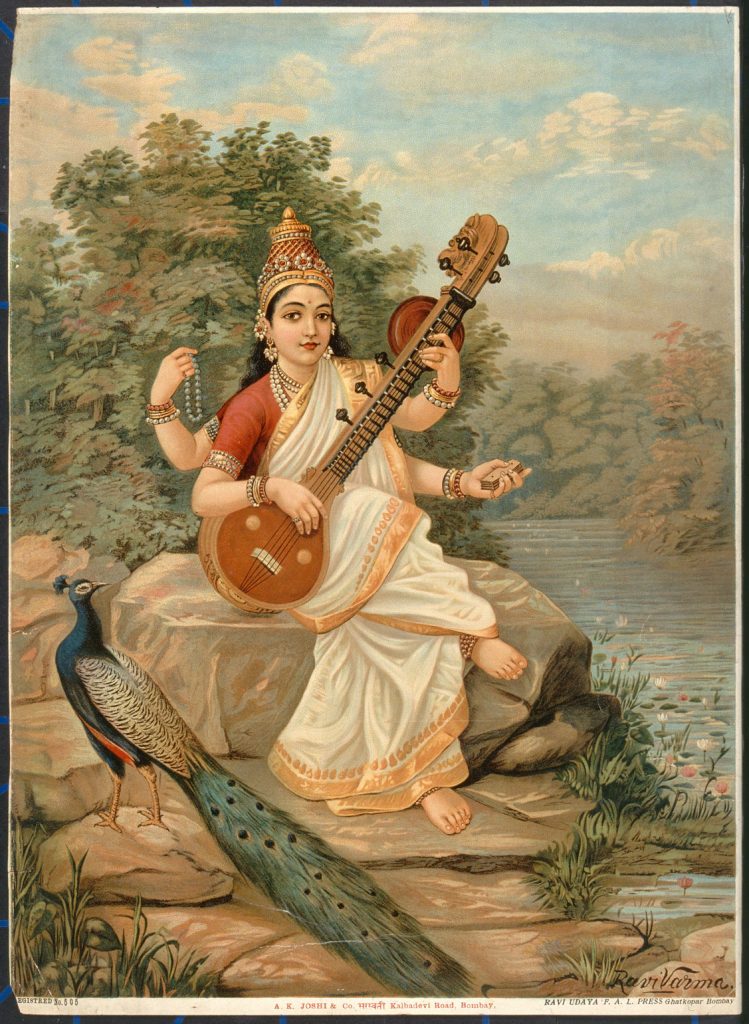

Saraswati, Goddess of Learning and the Arts

Saraswati bestows wisdom, particularly for devotees engaged in learning and artistic creation. Clad in a white sari, the goddess plays a vina, a large stringed instrument. She holds a string of prayer beads (mala) in her upper left hand and a sacred text in her lower right. Saraswati’s name translates to “the flowing one” in Sanskrit because in the ancient Hindu texts known as the Vedas, she embodies a sacred river that once flowed through the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent. This sense of flow is evident in the benefits she imparts: speech that is pure and eloquent, and creativity in all forms of artistic expression. Together with the goddess Lakshmi, Saraswati is often described as co-wife of the Hindu god Vishnu. In that context, she represents spiritual and transcendent goals, while Lakshmi represents worldly benefits and good fortune.

Wisdom as Artistry (detail)

White skinned, dressed in white, and seated on a white lotus, this luminous form of Saraswati glows against a dark maroon ground punctuated by two red poppies. Crowned and clad in a gold-edged sari, the three-eyed Hindu goddess of learning and the arts holds a text in her right hand and a string of prayer beads in her left. Her sidelong gaze and poised appearance evince the artist’s skillful linear style.

Image 1 of 4

Wisdom as Artistry (full artwork)

White skinned, dressed in white, and seated on a white lotus, this luminous form of Saraswati glows against a dark maroon ground punctuated by two red poppies. Crowned and clad in a gold-edged sari, the three-eyed Hindu goddess of learning and the arts holds a text in her right hand and a string of prayer beads in her left. Her sidelong gaze and poised appearance evince the artist’s skillful linear style.

Image 2 of 4

Temple in Miniature (full artwork)

The Hindu god Vishnu stands below a trefoil arch, flanked by his much smaller divine wives. The goddesses—Lakshmi at left, Saraswati at right—lean inward, creating a pleasing triangular formation with the god’s towering, crown-topped form. The earth goddess (Bhudevi) is typically depicted as Vishnu's co-wife along with Lakshmi, but in Odisha, India, where this shrine was made, Saraswati appears instead. Open latticework lightens the weight of the tower (shikhara) above, which resembles the regional temple architecture of this period.

Image 3 of 4

Divine Musician (detail)

With her broad shoulders, swaying posture, and hands delicately grasping a stringed instrument known as a vina, the Hindu goddess Saraswati exhibits both rhythm and strength. Her upraised chin suggests an aloof power that matches her prowess in music. As goddess of learning and the arts, she expertly fingers the chords with her left hand while plucking the strings with her right. A spherical gourd at the top of the vina amplifies her tune. Even today, musicians worship Saraswati before practicing their instruments or performing.

Image 4 of 4

Tara, Goddess of Great Compassion

In northwestern India and the Himalayan region, Tara is the foremost goddess of Buddhist practice. She embodies the Buddha’s great compassion. Her name means both “star” and “savior,” and scholars believe she was an important goddess for ancient seafarers. Gaining renown in the Mahayana (“great vehicle”) Buddhism of India by the sixth century, she was initially closely connected to the bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteshvara. A bodhisattva aspires to become a future buddha and vows to attain wisdom, generosity, and other qualities called perfections (paramitas). The highest-ranking bodhisattvas are believed to dwell in celestial realms, yet they appear endlessly on earth to help devotees. Tara has multiple important forms that rescue beings from peril. As White Tara, she heals, and as Green Tara, she removes obstacles along the path toward awakening.

Maximum Availability

In Tibetan Buddhism, Mahashri (“greatly glorious”) Tara, the goddess of compassion, is a high-level bodhisattva who duplicates herself endlessly throughout the world to aid beings. This thangka (painting on cloth) depicts Green Tara joined by her twenty-one principal earthly manifestations. Frothy pink lotuses punctuate the assemblage and form an elaborate throne for the goddesses, each of whom links to a central tree trunk. While they are depicted here in a cosmic realm, Tara’s multiple forms indicate that she can reside everywhere all at once.

Image 1 of 4

Maximum Availability (detail)

In Tibetan Buddhism, Mahashri (“greatly glorious”) Tara, the goddess of compassion, is a high-level bodhisattva who duplicates herself endlessly throughout the world to aid beings. This thangka (painting on cloth) depicts Green Tara joined by her twenty-one principal earthly manifestations. Frothy pink lotuses punctuate the assemblage and form an elaborate throne for the goddesses, each of whom links to a central tree trunk. While they are depicted here in a cosmic realm, Tara’s multiple forms indicate that she can reside everywhere all at once.

Image 2 of 4

Regal Reassurance

Artists assembled pieces of copper repoussé to create this stunning depiction of the Buddhist goddess Tara. Her downward, meditative gaze evokes peace. Rich turquoise inlays enhance her gilded form and draw attention to a magnificent, Tibetan-style crown. Her vase holds the nectar of immortality, representing long life, while her hand gesture of teaching urges devotees to rely on her in times of difficulty. The vase and mudra together identify her as White Tara, goddess of compassionate healing.

Image 3 of 4

Saving Grace

Easily held in the hand, this small sculpture of the goddess Tara served as a portable devotional figure for a Buddhist practitioner. One even smaller devotee, depicted at lower left, joins her hands in homage as the goddess’s upturned palm offers blessings. Tara stands in a graceful three-bend posture with a serene expression as she holds two lotuses that symbolize great compassion. Small bronze images of deities proliferated in Bengal during this period; using the same imagery, artists produced large-scale stone sculptures for temple shrines.

Image 4 of 4

Yoginis and Dakinis, Divine Tantric Practitioners

Yoga was not a form of exercise in India until the modern era but rather a practice of spiritual discipline involving intensive meditation and asceticism, methods for restraining the body and senses. Through these efforts, yogic practitioners aimed to realize union with the Absolute (or Brahman) in Hindu traditions and awakening in Buddhism. By the ninth century, some yogic practitioners adopted the techniques of tantra to gain immortality and supernatural powers. Stories convey the abilities of female and male practitioners (yoginis and yogins) to change shape, fly, or vanish at will. Hindu and Buddhist texts alike describe yoginis and their Buddhist counterpart, dakinis, as human women whose tantric asceticism, ritual prowess, and great wisdom propelled them to the status of goddesses.

Dynamic Wisdom

Because she bears a crown and a staff decorated with skulls, this brightly colored thangka (painting on cloth) likely depicts Vajrayogini, a dakini considered by Tibetan Buddhists to be a wise and powerful emanation of the Buddha. She is surrounded by a fiery red mandorla, and the bloody contents of her upraised skull cup emphasize her fearsome power to incinerate ignorance and reveal ultimate truths. The diagonal thrust of her lunging posture signals that dakinis can fly.

Image 1 of 4

Dynamic Wisdom (detail)

Because she bears a crown and a staff decorated with skulls, this brightly colored thangka (painting on cloth) likely depicts Vajrayogini, a dakini considered by Tibetan Buddhists to be a wise and powerful emanation of the Buddha. She is surrounded by a fiery red mandorla, and the bloody contents of her upraised skull cup emphasize her fearsome power to incinerate ignorance and reveal ultimate truths. The diagonal thrust of her lunging posture signals that dakinis can fly.

Image 2 of 4

Paradoxical Power

Yoginis are powerful goddesses who teach secret wisdom. Each has a unique appearance that synthesizes ferocious and nurturing qualities. This yogini clutches a household broom and dustpan in her upraised hands. A skull cup for drinking blood or liquor rests in her lower left hand, a snake slithers through her pierced right ear, and her hair streams out wildly—all signaling ferocity. Such competing signs of domesticity, untamed nature, and death reveal the yogini’s ability to overcome illusory perceptions and the suffering that results.

Image 3 of 4

A Force for Change

Naro Dakini’s vertical third eye above her knitted brow and flaming mandorla convey her enlightened wisdom in Tibetan Buddhism. She revels in the imagery of death so devotees might overcome their fear of it. A form of Vajrayogini, Naro Dakini teaches that the true nature of existence lies beyond the impermanent states of life and death. Her sharp flaying blade cuts through all ignorance. Her darkened face, originally painted gold, indicates that the sculpture sustained damage from a fire.

Image 4 of 4

Further Resources

Instructional Essay

Glossary

Find definitions for unfamiliar terms used in the exhibition here.

A person who practices asceticism, or the renouncing of worldly possessions and family life to pursue religious or spiritual goals. In South Asian religions historically, ascetics commonly performed challenging acts of self-denial, including restraining the senses through meditation (see also yoga)

An earthly incarnation of the Hindu deity Vishnu; from the Sanskrit verb tṛ, “to cross,” as in to cross between realms.

(“Old Stories of the Lord”) an important Hindu text (ca. tenth century CE). Its tenth chapter tells of Krishna’s life on earth in a village in India.

One who aspires to become a Buddha. In Mahayana Buddhism, a bodhisattva ascends ten levels (or bhumis) on the path to enlightenment.

In Hindu traditions, brahman is the divine source of all things; it is eternal, all-pervasive, and formless.

In Buddhist traditions, (“Awakened One”) a fully awakened or enlightened being who is no longer subject to the cycle of death and rebirth.

In tantric Buddhism, fierce female guardians who offer secret teachings to advanced practitioners (see also tantra below).

Refers to a mutual exchange accomplished through a meeting of the eyes. In religions indigenous to India, devotees see and are seen by the deity or enlightened being who is present within a consecrated image or object. This exchange confers blessings.

Goddess in Sanskrit; also a shortened form of the name of Mahadevi (Great Goddess) in Hindu traditions.

(“Glory of the Goddess”) the ca. fifth-century CE Hindu text that relates the narrative of Durga’s triumph over evil as well as the creation of Kali/Chamunda and each goddess’s glory on the battlefield.

In Buddhism, a type of long-form mantra.

In Hinduism, a moral code to live by for a person or social group; in Buddhism, the historical Buddha’s teachings.

The Hindu god Vishnu’s eagle mount or vehicle.

(“Song of Krishna”) Hindu poetic narrative text by Jayadeva that tells the love story of Krishna and Radha. Krishna is alternately known as Govinda (“King of Cowherds”).

The cow-herder women who became ardent devotees of the Hindu deity Krishna when he lived in a village on earth, as recounted in the Bhagavata Purana.

(“Great Goddess”) or Devi (“goddess”) Hindu conception of the goddess as the source and creator of all things.

(“great ritual knowledge”) A group of ten deities who embody the animating female energy of the universe (shakti) in Tantric Hinduism; also a type of mantra embodied by a goddess in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions (see also shakti, mantra).

(“Great Vehicle”) the Buddhist path that emphasizes becoming a bodhisattva.

A string of prayer beads used when reciting mantras (powerful sacred syllables).

A sequence of powerful sacred syllables, usually associated with invoking a specific deity.

Liberation from our world of samsara, the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

A sacred hand gesture that conveys a specific, culturally agreed-upon meaning; in tantric contexts, a hand gesture that generates spiritual power.

(“perfection”) In Mahayana Buddhism, six (or later ten) methods of purifying or perfecting one’s body, speech, and mind to attain awakening.

In Buddhism, the wisdom of enlightenment (wisdom that awakens the mind).

(“perfection of wisdom”) A genre of texts personified by a goddess, and the sixth perfection in Mahayana Buddhism.

An item, often a small sweet, which is blessed by the deity and then given to devotees after they receive darshan (see also darshan).

(“old”) A genre of early Hindu texts that tells the stories of Hindu deities (ca. first millennium CE).

Hindu poetic narrative written by Keshavdas in 1591 that uses the long-standing tropes of the hero and heroine to describe the love between Krishna and Radha.

An artistic technique of hammering sheets of metal on the reverse side to produce sculptural forms.

In Buddhism, a ritual for invoking the powerful presence and protection that deities bestow. The ritual typically uses a thangka, or painting on cloth, to aid the practitioner in visualizing that the central deity resides in one’s heart.

The endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

Khmer term for a long, sarong-like skirt worn by deities in Southeast Asian sculptures.

In Hinduism, an epithet for Devi that describes her as the animating female energy of the universe.

A sacred verse, teaching, or a genre of religious texts used for teaching. In this exhibition, it refers to a Buddhist text, specifically of the Mahayana tradition.

Ritual methods into which one must be initiated, typically by a teacher (guru) into a lineage. Many tantric rituals are secret, some purposefully transgressing social customs and taboos (for more, please see the Wisdom of the Goddess section on yoginis and dakinis).

Tibetan term for Tibetan Buddhist painting on cloth.

The earliest texts associated with Hindu traditions. The Vedas were orally composed and transmitted over many centuries, beginning as early as 1500 BCE, according to some experts. The latest of the Vedic texts, the Upanishads, may have been composed around the fifth century BCE.

A long-necked lute or stringed instrument with a round, wooden body attached to a neck that is associated with the Hindu goddess of learning, Saraswati. Fitted to one or both ends of the vina, the round gourd acts as a resonator.

A discipline involving intensive meditation and ascetic practices (see ascetic above) that emerged in ancient India. Through these efforts, yogic practitioners aimed for the highest spiritual wisdom.

In religions indigenous to India, powerful goddesses who teach secret wisdom. Most yoginis have both ferocious and nurturing qualities.

Related Exhibitions

-

The Art of Knowing in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Himalayas

TEMPORARILY CLOSED

All works are from the National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution (left to right): Mahashri Tara and the twenty-one Taras, Arthur M. Sackler Collection, The Alice S. Kandell Collection, S2017.49; Radha pining for Krishna, from a Gita Govinda manuscript, Freer Collection, Gift of Mr. Paul F. Walter, F2005.7; Dakini, Arthur M. Sackler Collection, The Alice S. Kandell Collection, S2017.62.2; Saraswati, folio from a Goddess series, attributed to Wajid, Purchase and partial gift from the Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection—funds provided by the Friends of the Freer and Sackler Galleries, S2018.1.40

- Jump To...