February 24–August 5, 2018

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery | Gallery 27a and 27b

-

Collection Area

Arts of the Islamic World

In our age of social media and selfies, it may be difficult to grasp the importance of painted portraits and studio photographs in nineteenth-century Iran. During this time, known as the Qajar era, rulers such as Fath-Ali Shah (reigned 1797–1834), a contemporary of Napoleon, and Nasir al-Din Shah (reigned 1848–96), a contemporary of Queen Victoria, used portraiture to convey monarchical power and dynastic grandeur. Through a selection of about thirty works from the Freer and Sackler collections, which include recent major gifts and acquisitions, this exhibition explores how Persian artists transformed modes of representing royalty and nobility. Paintings on canvas, lacquerwares, and photographs also highlight Iran’s complex artistic and cultural interactions with the West as European conventions and new technologies were being introduced.

This exhibition is made possible with generous support from Patricia and Alex Farman-Farmaian.

Additional Highlights from the Archives

-

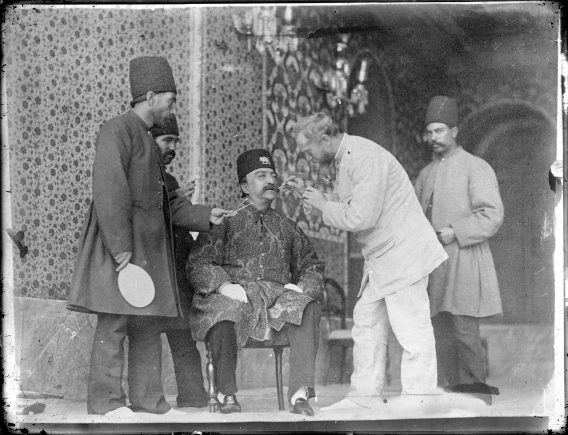

Nasir al-Din Shah with his Austrian dentist

Throughout his rule, Nasir al-Din Shah (reigned 1848–96) enthusiastically embraced the art of photography, a technology that was introduced to Iran as early as the late 1840s. The monarch was an avid amateur photographer and actively recorded his personal life and that of his court.

Nasir al-Din Shah also took advantage of every opportunity to be photographed, whether in standalone portraits or in group pictures while engaged in various activities. Although they convey a sense of instantaneity, these images were the carefully staged work of professional court photographers (in Persian, akkash-bashi). Unlike paintings hung on the wall, photography was not meant for public display; rather, photographs were arranged inside albums to be viewed during private gatherings or by individuals. -

Studio Portrait: Ahmad Shah Qajar (approximately age 12)

The last Qajar ruler, Ahmad Shah, came to the throne at the age of eleven and was under the control of regents until his coronation in 1914. Although not much is known about his childhood, Ahmad Shah belonged to a generation for which photography was ubiquitous, used as the primary medium to record daily life.

Ahmad Shah Qajar and his Cabinet; S2013.4

- Jump To...

Explore All Pieces in this Section

Shahnama (Book of kings) by Firdawsi (d.1020)

-

Period

Safavid period (text) and Qajar period (illustrations and cover)

-

Geography

Iran

-

Material

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper (text and illustrations); brown leather tooled binding with lacquered cartouches (cover)

-

Accession

S2014.17.4

In this copy of Iran’s national epic, Firdawsi’s Shahnama (Book of Kings), Fath-Ali Shah (reigned 1797–1834), with his characteristic long black beard, arching eyebrows, and slender body, appears as the legendary hero Rustam. The ultimate defender of Iran’s sovereignty, Rustam personifies valiance, strength, and loyalty. Associating the ruler with the mythical paladin was meant to affirm the Qajar dynasty’s power and its place within the history of Persian monarchies.

Mirror case with a portrait of Muhammad Shah Qajar, Nasir al-Din, and Haji Mirza Aqasi

-

Period

Qajar period

-

Geography

Iran

-

Material

Watercolor, gold-colored pigments on pasteboard

-

Accession

S2014.17.89a-b

The relatively short rule of Muhammad Shah (reigned 1834–48) is often seen as a transition between his grandfather Fath-Ali Shah and his successor, Nasir al-Din Shah. During Muhammad Shah’s reign, monumental painting declined in favor of small-scale lacquered works and single-sheet portraits. This portrait of Muhammad Shah, who is recognizable by his short black beard and conical lambskin hat adorned with imperial ornaments, is painted inside the cover of a mirror case.

Pen case with probably Nasir al-Din Shah in a landscape

-

Period

Qajar period

-

Geography

Iran

-

Material

Watercolor, gold-colored pigments, and lacquer on pasteboard

-

Accession

S2014.17.49a-b

Lacquered objects became favorite vehicles for royal imagery in the Qajar era. This pen case offers an example of Nasir al-Din Shah’s portrait, which must have been made not long after he ascended the throne in 1848. The shah sports regalia including a tall, conical hat with a jeweled ornament and a heron’s feather. Although depicted in a stylized and somewhat idealized manner, Nasir al-Din Shah (reigned 1848–96) is still recognizable by his prominent moustache.

Mirza Muhammad Khan Qajar

-

Period

Qajar period

-

Geography

Iran

-

Material

Opaque watercolor and ink on paper

-

Accession

S1999.21

A textile handwoven from silk and wool served as the material par excellence for the shah. Known as termeh in Persian, it is usually decorated with paisley motifs in bright colors, mainly jujube red and orange. After Muhammad Shah’s accession to the throne, Qajar rulers regularly bestowed termeh robes of honor (khil‘at) upon princes and members of the ruling elite. Termeh was an important symbol of social prestige, which explains its presence in many portraits of Qajar shahs and noblemen. This one depicts Mirza Muhammad Khan, who was chief of the royal guards of Nasir al-Din Shah and later appointed commander-in-chief of the army and prime minister.

Jalal al-Din Mirza, son of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar (reigned 1797-1834)

-

Period

Qajar period

-

Geography

Iran

-

Material

Oil on canvas

-

Accession

S2016.9a-b

A cosmopolitan, polyglot, and radical freethinker, Prince Jalal al-Din Mirza was the fifty-fifth son of Fath-Ali Shah. This painting was completed in 1859, when the prince was thirty years old. Although unsigned, it is characteristic of the prominent Qajar artist Abu’l-Hasan Ghaffari, Sani‘ al-Mulk, who trained in Iran and sojourned in France and Italy. The artist’s distinct style—capturing the sitter’s physical likeness and psychological state, and blending Western conventions with Persian abstraction—lends the painting a subtle intensity.

Though a marginal figure in Qajar royal politics, the prince would write an unprecedented history of Iran known as the Book of Rulers (Nama-i Khosravan). Composed in “pure Persian” expunged of Arabic and Turkish words, it was the first work to promote a distinct Persian identity, devoid of foreign influences. The account also forges a political and cultural continuum from the country’s pre-Islamic past to the Qajar dynasty.

Box with writing utensils, decorated with photographs of Nasir al-Din Shah, his sons and ministers, and views of Paris and Tehran, and with calligraphic lithographs

-

Period

Qajar period

-

Geography

Probably Tehran, Iran

-

Material

Lacquered, painted, and gilded wood with applied photographs and silver fittings

-

Accession

S2014.11.1

One of Iran’s most popular photographic formats was the small carte de visite, or calling card. These cards were collected by and exchanged among the elite and often mounted into albums. The designer of this large box used cartes de visite to replace the painted images that traditionally adorned lacquered objects.

Pen case with Nasir al-Din Shah and rulers from the Shahnama

-

Period

Qajar period

-

Geography

Isfahan or Tehran, Iran

-

Material

Watercolor, gold-colored pigments, and lacquer on pasteboard

-

Accession

S2014.17.65a-b

This pen case powerfully connects the Qajar era with Iran’s past. The central medallion depicts Nasir al-Din Shah on the Peacock Throne, surrounded by his sons, ministers, and court members. The remainder features scenes from Firdawsi’s Shahnama (Book of Kings), Iran’s national epic. By appearing among mythical monarchs and heroes, Nasir al-Din Shah assumes his role as King of Kings (Shahinshah)—the title of ancient Iranian rulers, which his great-grandfather Fath-Ali Shah had revived. While the shah and his immediate companions are based on careful observation and photographs, the surrounding literary figures are idealized and abstracted.

Pen case with portrait medallion of a Qajar dignitary

-

Period

Qajar period

-

Geography

Iran

-

Material

Watercolor, gold-colored pigments, and lacquer on pasteboard

-

Accession

S2014.17.82a-b

Members of the Qajar household followed the shahs’ example by commissioning works of art, including their own portraits. Such images followed prescribed rules in their arrangement and composition. These formal norms were also translated into other media, especially lacquer. This pen case is decorated with the portrait of an unidentified Qajar nobleman.

Ahmad Shah Qajar and his Cabinet

-

Period

Qajar period

-

Geography

Iran

-

Material

Oil on canvas

-

Accession

S2013.4

This monumental portrait of Ahmad Shah is a unique pictorial document of artistic and political significance. The painting encapsulates both Iranian conventions in the rather flat treatment of bodies and European naturalism in the faces. It also reveals a major shift in the monarchy’s power.

The work was displayed in Tehran’s Gulistan Palace, as testifies this copy of a photograph taken during the painting’s installation. Comparing the two shows that the painting was originally undated. The signature and the date of AH 1328 (1910) at lower right were added later, as were the identifications at top. From 1909 to 1914, two successive regents governed as the shah came of age. The second regent, Nasir al-Mulk, is depicted alongside other cabinet members. One only held office in early 1914, which helps date the painting to that year.

This formal gathering may reflect the aftermath of the Constitutional Revolution (1906–11), for the monarchy is no longer absolute. The underage shah appears here dominated by the ministers behind him. Wearing termeh robes of honor, the elderly princes Abd al-Husayn Farman-Farma (left) and Abd al-Majid Ayn al-Dawla (right) were among the most prominent figures in Iranian politics after 1900.

Jay A. Bisno Collection of Sevruguin Photographs

Throughout his rule, Nasir al-Din Shah (reigned 1848–96) enthusiastically embraced the art of photography, a technology that was introduced to Iran as early as the late 1840s. The monarch was an avid amateur photographer and actively recorded his personal life and that of his court.