July 13, 2024–July 26, 2026

-

Dates

-

Location

Freer Gallery of Art | Gallery 10

-

Collection Area

American Art

American painters Willard Metcalf, Dwight Tryon, Winslow Homer, and Abbott Thayer created profoundly beautiful views of the New England landscapes where they lived and worked. These paintings largely depict that environment as timeless and static. Shifting Boundaries looks at these works from a new angle by engaging a multiplicity of voices and viewpoints to explore what these paintings can tell us about changes to this region both past and present. As Shifting Boundaries reveals, the views these artists created of pasturelands in Massachusetts and of seascapes in Maine were transforming even as these artists recorded them. This reshaping of these landscapes has only accelerated in the century since Metcalf, Tryon, Homer, and Thayer depicted them.

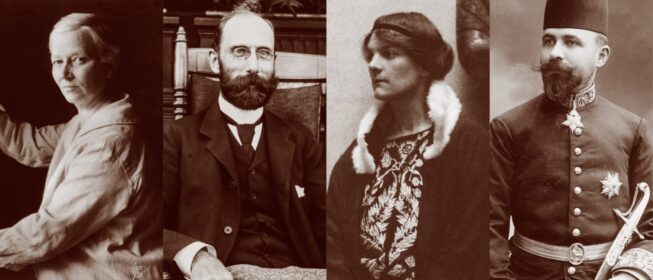

Shifting Boundaries pilots a new mode of collaborative curatorial practice. NMAA Lunder Curator of American Art Diana Greenwold, curatorial assistant Mary Mulcahy, and interpretation specialists Liz Gardner and Amy Freesun partnered with Lauren Brandes (Smithsonian Gardens), Dennis Chestnut (Groundwork Anacostia River DC), Jerome Foster II (Waic Up), Elizabeth James-Perry (Aquinnah Wampanoag artist), Lorette Picciano (Rural Coalition), Stephanie Toothman (National Park Service), and Melinda Whicher (Smithsonian Gardens) to develop the themes for the exhibition, select works of art, and write object labels. The group’s perspectives, drawn from their individual areas of professional expertise and their own personal experiences, allow us to see new details in these stunning works of art. The landscapes become invitations to explore a century of human impact on New England land and water, the erasure of indigenous histories, and the environmental changes that are altering this region today.

About the Collaborators

Lauren Brandes

Lauren Brandes

As a child, Lauren Brandes’s family vacations involved watching seemingly endless miles of urban skylines, forests, and countryside pass by during long road trips to visit far-flung national parks and American cities. Now as a parent, she enjoys sharing that love of travel and adventure with her own family. Lauren’s interest in both nature and the built environment led her to the profession of landscape architecture. As a landscape architect with Smithsonian Gardens, she hopes to help others feel a sense of delight and stewardship about the natural world through public gardens.

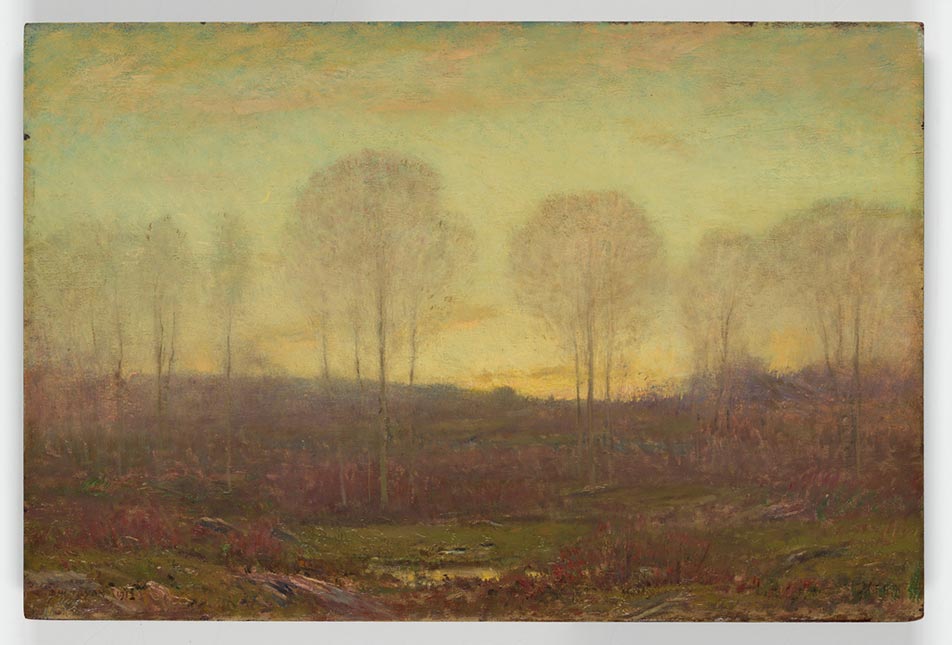

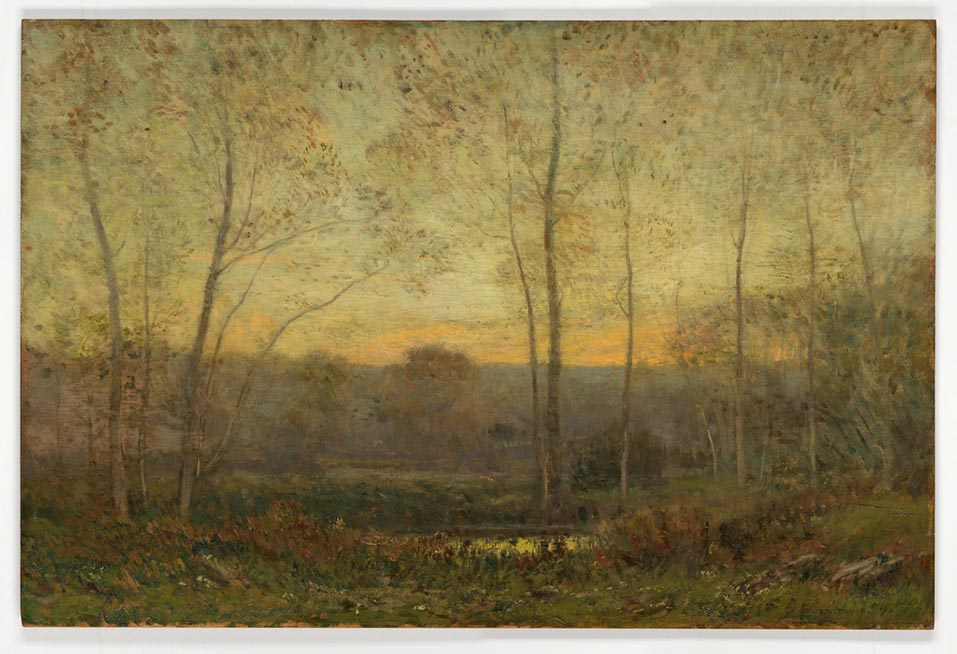

What looks like a peaceful pastoral scene reveals hints of what has been lost in this landscape. The narrow, spindly trees suggest they matured amongst a denser forest that is now gone. As New England landowners cleared the land for farms and agricultural production, they also destroyed ecosystems and wildlife habitats. The wide spaces between trees and the overall openness in this view make you wonder what happened to all the animals, insects, and plants that previously filled those voids.

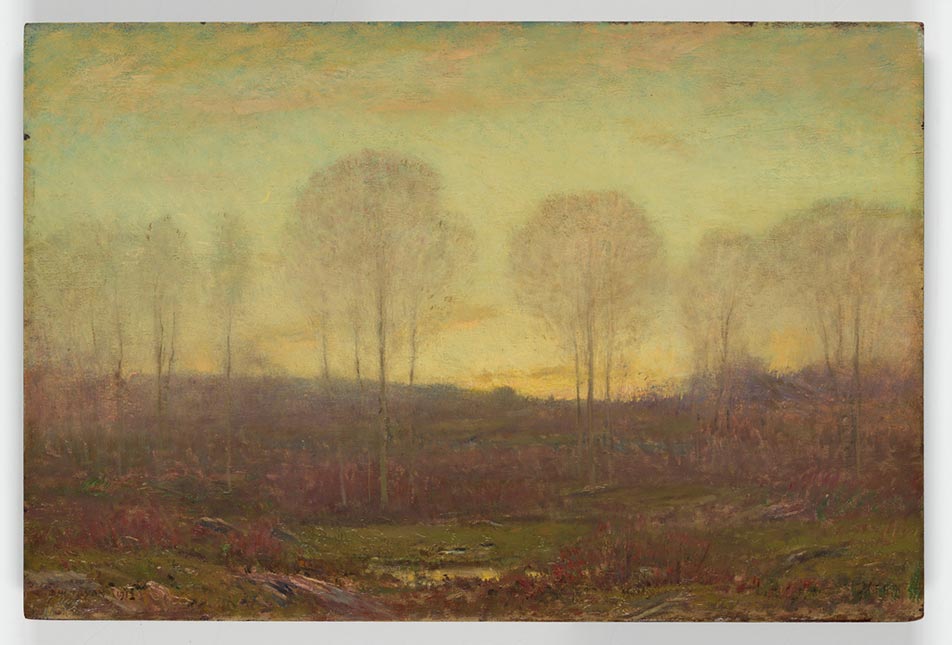

Twilight: November

Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925)

United States, 1912

oil on wood panel

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1912.14a–b

Image 1 of 3

Broad brushstrokes and variations in green evoke a densely vegetated view. While Twachtman’s depiction is imprecise, his abstracted image may be more representative of how many people perceive plants as merely a blurred background of green that they can mostly ignore. Plant blindness—the inability to notice plants in our own environment—can keep us from recognizing the importance of what grows around us. If we don’t appreciate and take note of the plant life, how can we expect to protect it?

The Hidden Pool

John Henry Twachtman (1853–1902)

United States, ca. 1899

oil on canvas

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1913.32a–c

Image 2 of 3

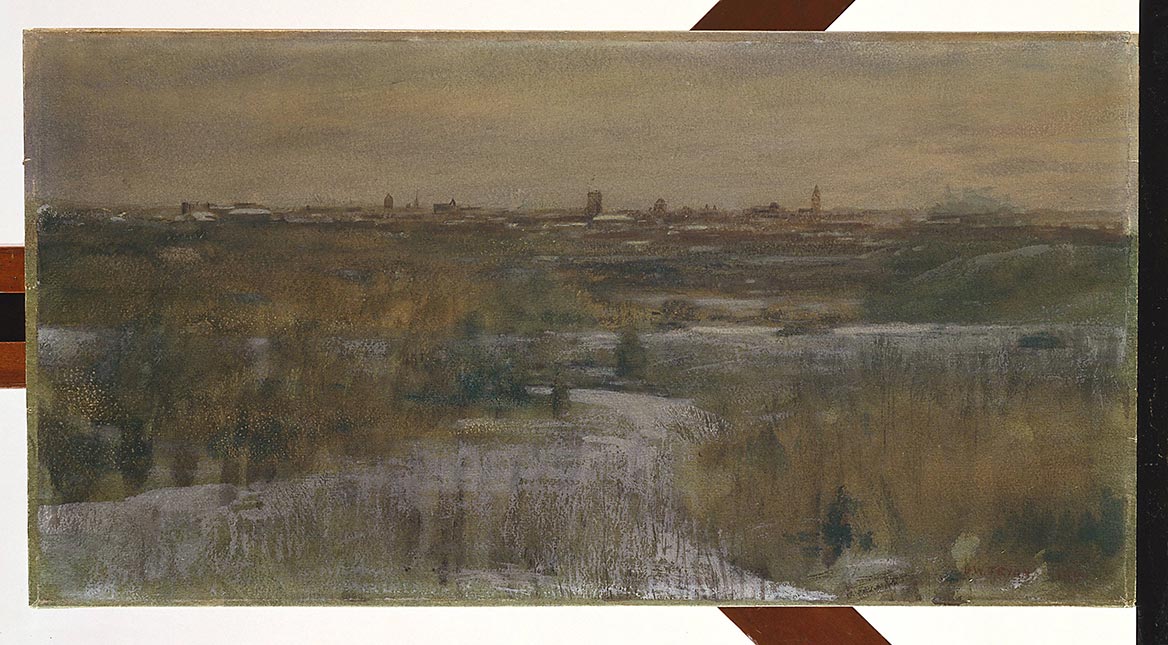

The looming New York City skyline in the background hints that humans exist at the edge of this natural scene. One realm seems entirely man-made and the other crafted by ecological forces. However, both are the work of human design. What appear like natural rolling hills and pockets of trees are in fact deliberately constructed and intentionally planted elements creating a picturesque and idealized landscape. Central Park may look untouched, but it is as designed and intentional as the cityscape behind it.

Central Park: Moonlight

Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925)

United States, 1894

pastel on brown paper

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1906.87a–b

Image 3 of 3

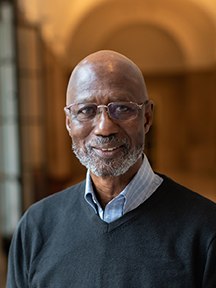

Dennis Chestnut

Dennis Chestnut

Dennis Chestnut is the board chair of the Ward 7 Resilience Hub Community Coalition in Washington, DC, and former founding executive director of Groundwork Anacostia River DC. Dennis is a native Washingtonian, vocational and environmental educator, and community organizer. He is a civic ecologist and works to improve the quality of life for DC residents through building stewardship of their natural environment and local community. Dennis was named 2019 National River Hero by the River Network at the 2019 River Rally.

The unique time of day that can be described as Almost. Almost the end of daylight. Almost evening just before night. Subtle, delicate, quiet, and precise. Complex but simple and calm. The beauty of an undisturbed landscape at one of the most beautiful times of the year: autumn. The presence of wildlife in its natural habitat. Water at the center of the landscape, as it is at the center of life.

Twilight: November

Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925)

United States, 1912

oil on wood panel

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1912.14a–b

Image 1 of 2

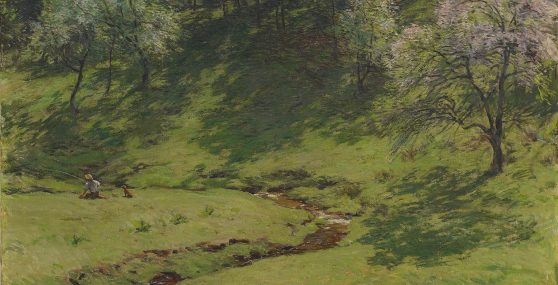

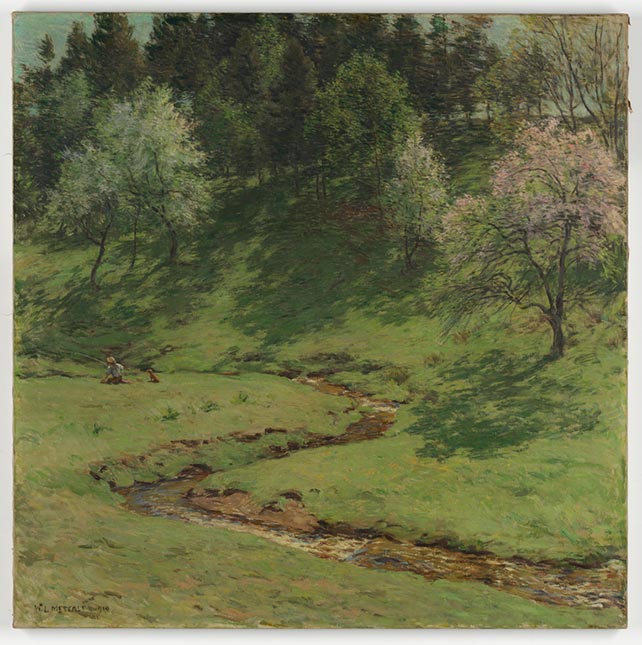

The New England countryside in 1915 is a very different place and time from 1968 in Parkside, a community in Washington, DC, on the east side of the Anacostia River. That year, a seven-year-old boy and his friends went to play at a nearby stream near the river, much like the one we see in this painting. As in Blossom Time, these kids were fortunate to have a local stream to visit, play in, and relax by. However, the Parkside stream was next to a landfill, and these boys could not relax because the neighborhood was dangerous. That seven-year-old boy died in a fire set to rid the landfill of trash and debris. Fifty-three years apart, both locations on the East Coast, little boys, a stream, and very similar but different landscapes.

Blossom Time

Willard Metcalf (1858–1925)

United States, 1910

oil on canvas

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1915.27a–b

Image 2 of 2

Jerome M. Foster II

Jerome Foster II is an African American climate activist, social entrepreneur, and public speaker. He is one of the organizers of Fridays for Future, a youth-led climate strike movement, and has been a leading voice for Black visibility in climate activism. In March 2021, Foster was appointed as an advisor to the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, becoming the youngest person ever to do so. Foster also led the OneMillionOfUs initiative to register one million young people to vote. He is the cofounder and executive director of Waic Up, a climate justice advocacy nonprofit organization that uses art, journalism, and civic engagement to create change.

As a member of Generation Z viewing this seemingly tranquil painting, I instantly feel a sense of anxiety rather than calm. The harmonious interaction of figures within the lush green background depicts an idealized relationship with nature—one of balance, respect, and coexistence. The reality of our environmental impact, however, is often dissonant and exploitative, a tension that the corporate practice of greenwashing obscures by seducing consumers with illusions of sustainability. Yet, I feel a note of hopefulness when I imagine the gathered figures as leaders and changemakers aware of the power

in coming together for a common purpose.

The Lute

Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851–1938)

United States, 1904

oil on wood panel

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1913.34a–b

Image 1 of 2

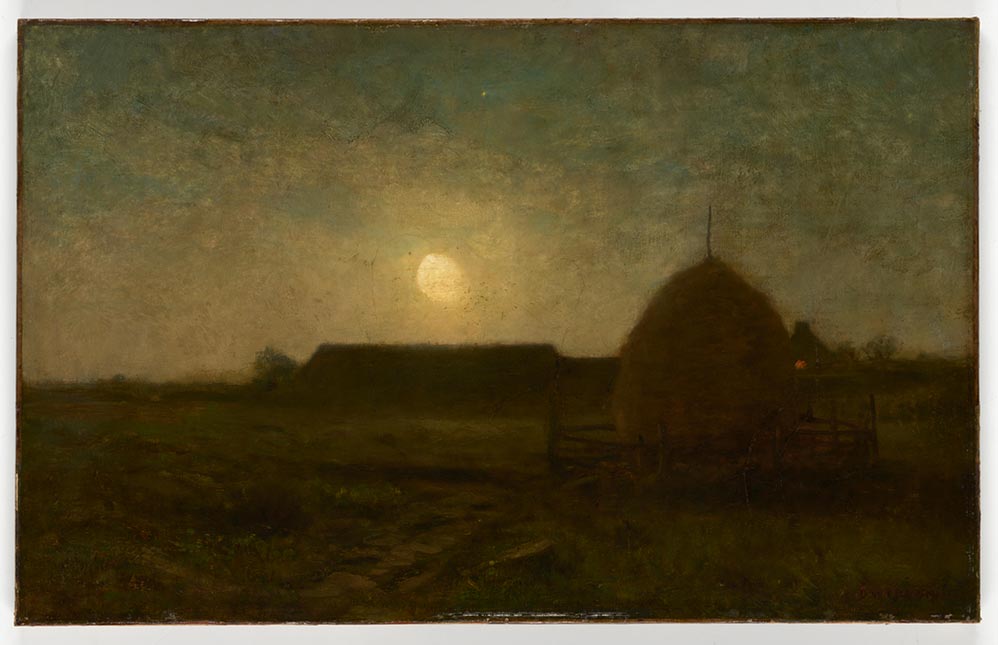

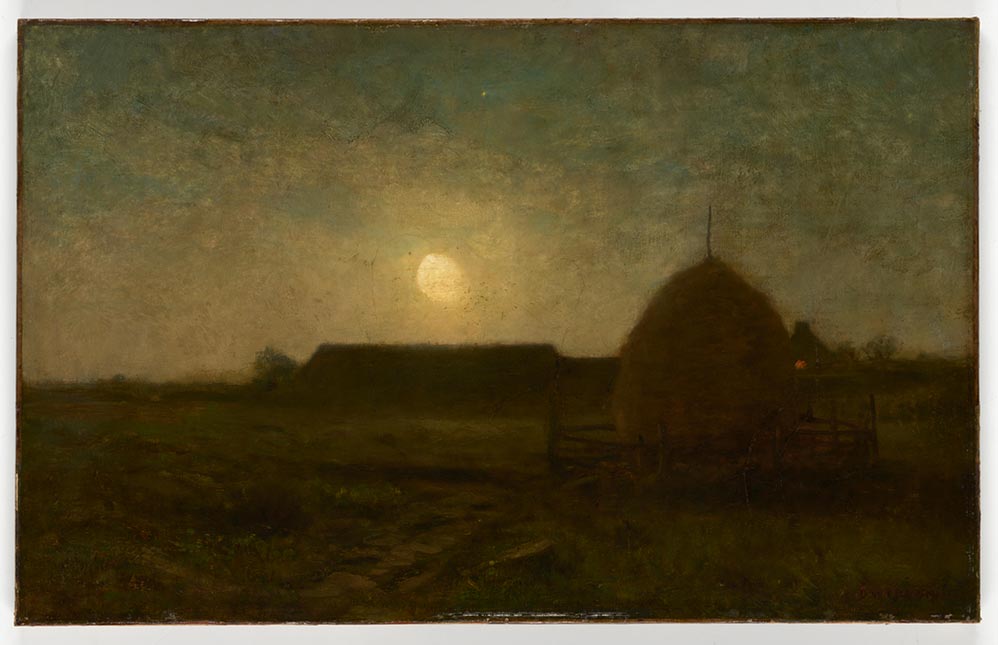

Moonlight draws me into a moment of stillness, reminding me to pause, breathe, and appreciate the quiet beauty of our planet and our role in both giving to it and taking from it. The light coming from the house suggests the presence of a family who works on the land. The bright moon illuminates texture in the foreground, a visualization of these farmers shaping the soil to make things grow. In an age when impacts of human activity on the environment are undeniable, this painting is a powerful reminder of the costs of "progress" and the balance we can still strike between humanity and nature.

Moonlight

Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925)

United States, 1887

oil on canvas mounted on wood panel

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1891.2

Image 2 of 2

Elizabeth James-Perry

Elizabeth James-Perry

2023 NEA National Heritage Fellow Elizabeth James-Perry is an Aquinnah Wampanoag whaling descendant, a writer, and an artist. She designs wampum jewelry, naturally dyed weavings, and porcupine quillwork. Her garden installations encourage pollinators and educate about Native land stewardship. Her art was in the play Manahatta and was featured on the TV series Rutherford Falls. Perry has a marine science degree from the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. As a member of a tribal nation on Noepe (Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts), James-Perry’s perspective combines Traditional Ecological Knowledge, genealogy, art, and science.

The deep shade of healthy fir trees parts to invite the viewer to trudge through newly fallen snow toward mountain peaks. For centuries, Eastern Woodland Native families employed wooden snowshoes to travel on such deep snow and ice. I miss the snow and good maple syrup harvests, now that climate change makes both unpredictable in the Northeast.

The word Monadnock likely means “abundant land” in the Wampanoag and Abenaki languages. Perspective is important in Native languages, and place names figure in our traditional stories. The theme of erasure comes to mind. It is ironic that words from Native languages survive where many tribal communities were pushed out long ago. What is the fascination with tribal names for landmarks when Indigenous people who long resided here and possess the knowledge and connection to the land are not given much thought?

Monadnock No. 2

Abbott Handerson Thayer (1849–1921)

United States, 1912

oil on canvas

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1913.93a–b

Image 1 of 3

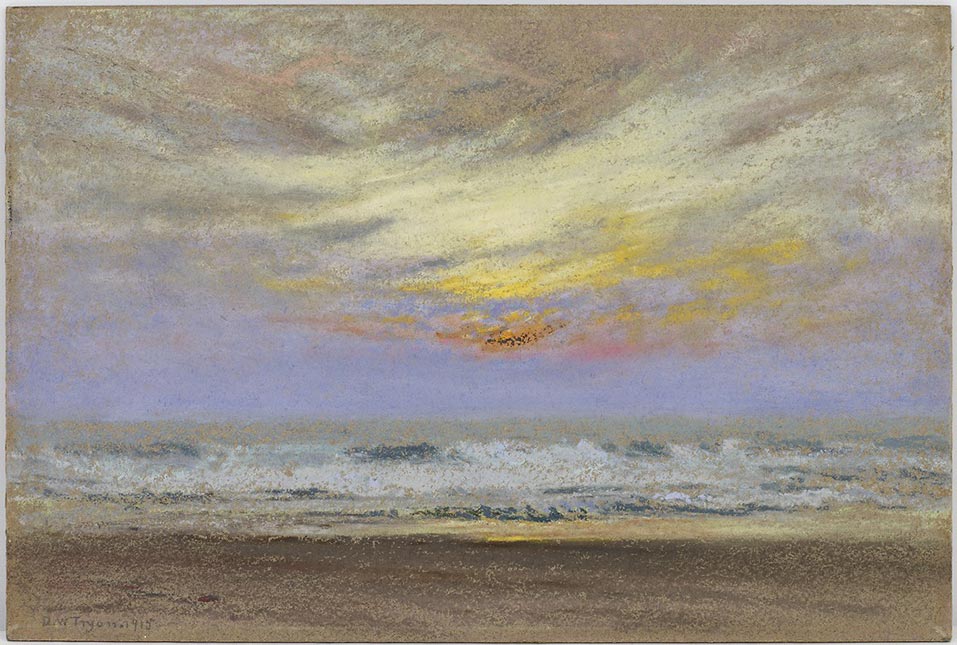

Tryon’s evocative pastels capture delicate colors in the sky and the kinetic energy of the Atlantic Ocean. The layered texture of pastel makes me pause to consider the work’s materiality and the mineral characteristics of the land itself. I wonder where the artist sourced his materials. My tribal community is situated on the Aquinnah clay cliffs, which are red, black, white, lavender, gray, and yellow from past ages. These minerals are used in pottery and were an important landmark for mariners. Does Tryon’s warm palette demonstrate continuity, expansion, or a shift in materials from previous artists who saw and used this land’s resources?

Sunrise

Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925)

United States, 1915

pastel on cardboard

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1915.132a–b

Image 2 of 3

Tryon’s evocative pastels capture delicate colors in the sky and the kinetic energy of the Atlantic Ocean. The layered texture of pastel makes me pause to consider the work’s materiality and the mineral characteristics of the land itself. I wonder where the artist sourced his materials. My tribal community is situated on the Aquinnah clay cliffs, which are red, black, white, lavender, gray, and yellow from past ages. These minerals are used in pottery and were an important landmark for mariners. Does Tryon’s warm palette demonstrate continuity, expansion, or a shift in materials from previous artists who saw and used this land’s resources?

Northeast Wind

Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925)

United States, 1915

pastel on cardboard

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1916.124a–b

Image 3 of 3

Lorette Picciano

Lorette Picciano

Born in New York City, Lorette grew up in upstate New York as the daughter of an engineer and a talented artist. She graduated from the New York State College of Agriculture at Cornell University and holds a master’s in education from the University of Hawai’i. She began working on policy with interfaith communities in Washington, DC, on the food and farm crises of the 1980s. Joining Rural Coalition as executive director in 1991, she now works with a diverse board and leaders in the long struggle for civil rights and equity in agriculture. She is currently engaged in her ninth Farm Bill debate to support these farmers.

The moon is rising—maybe not at night, but before dawn—revealing a towering pile of hay, stacked in those days not with a tractor but a pitchfork. The farm aglow in the moonlight reminds me of family road trips in the 1960s. My mother would notice the light on in the windows of houses we passed—the family waking up to the hard, never-ending work of a small dairy farm. How many morning lights have gone out, extinguished since Tryon painted this one? Factory farms distribute milk to ever fewer grocery stores, generating towering piles of waste and profiting investors over small farmers.

Moonlight

Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925)

United States, 1887

oil on canvas mounted on wood panel

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1891.2

Image 1 of 2

Why this sinister-looking cow? Itself an immigrant from Europe, the cow provided a familiar food for growing immigrant populations in northeastern cities in the 1870s. Is this the view from a milking stool as someone struggles to fill the pail so they can feed their family and squeeze out a few pennies for dry goods? The red cow stands in a dark and indistinct landscape and seems to portend what’s coming: pasteurization and refrigeration will make her milk safe to ship to urban centers to meet growing demand. Though she came as an immigrant herself, will she be pushed to her limit to sustain newer arrivals? How will she feel about milking machines?

The Red Cow

Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917)

United States, ca. 1870

oil on wood panel

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1908.25a–b

Image 2 of 2

Stephanie Toothman

Stephanie Toothman

Stephanie grew up in one of Massachusetts’s oldest townships, surrounded by landscapes reminiscent of Dwight Tryon’s paintings. After attending Smith College and the University of Pennsylvania, where she majored in history and cultural anthropology, Stephanie joined the National Park Service. She supported parks and partners in preserving cultural resources and carrying out National Historic Preservation Programs in the Pacific West and across the nation. After retiring in 2017 as associate director for cultural resources, partnerships, and science, Stephanie returned to her home in Seattle, Washington, and continues to support local preservation groups. She continues to represent the National Park Service for special partnership projects.

The stillness of Homer’s pair of female figures set against the background of the rugged coast embodies the fortitude of Maine’s maritime communities. The women remind me of my grandmother’s family, who lived on Nova Scotia’s coast. Their father left Canada for work in New England before returning to raise a family and work as a ship captain. His girls left their coastal town for Boston in 1910, bringing their strength and self-sufficiency as they sought greater opportunities for women.

Early Evening

Winslow Homer (1836–1910)

United States, painted in 1881; reworked in 1907

oil on canvas

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1908.14a–b

Image 1 of 2

Tryon captures a landscape and way of life on the cusp of transition. After thousands of years shaped by Indigenous peoples, the landscape his painting depicts reflects 250 years of Euro-American settlement, with boundaries defined by stone walls and tree lines. Over the century, farmers moving west for available lands under the Homestead Act, industrialization, and suburbanization reshaped this land once again. Obscured by today’s denser development and forest regrowth, remnants of these stone walls still survive as reminders of this agrarian past.

Autumn Morning

Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925)

United States, 1908–1909

oil on wood panel

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1910.4a–b

Image 2 of 2

Melinda Whicher

Melinda Whicher

Melinda Whicher has been a supervisory horticulturist with Smithsonian Gardens for four years, and her responsibilities include all of the South Mall gardens from the National Museum of Asian Art to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Prior to this role, she was the manager of Kings Landing Park in southern Maryland, where she completed several natural and historic preservation projects. Whicher also spent seven years as a horticulturist at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo. She holds a bachelor’s degree in horticulture from the University of Maryland and a master’s degree in recreation and park management from Frostburg State University.

Color is softened or eclipsed when the land is veiled under a blanket of snow. This does not diminish the beauty of the land but changes it into shadows, shapes, curves, and mysteries. Is there a frozen creek between the hills, lined with twiggy shrubs and low-lying brush? Is it silent, or can you hear the crinkling of ice crystals and the chirping of birds? Close your eyes and imagine the ever-changing land, hiding springtime greens and golds, a bubbling creek singing as it feeds the thick vegetation around it.

The White Pasture

Willard Metcalf (1858–1925)

United States, 1917

oil on canvas

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1917.249a–b

Image 1 of 2

Water is life. Although darkness is falling, a glimmer of reflection from a golden pond shines through the greenery along the water’s edge. Perhaps the artist was walking through a clipped pasture and, ignoring the sheared fields around him, chose to capture this oasis of wild growth, inspired by the rustling autumn leaves, the scent of fresh earth, the spark of light on the water, and the dark silhouettes of nature.

Evening: September

Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925)

United States, 1912

oil on wood panel

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1912.7a–b

Image 2 of 2

Support

This exhibition is made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art.

Related Exhibitions

-

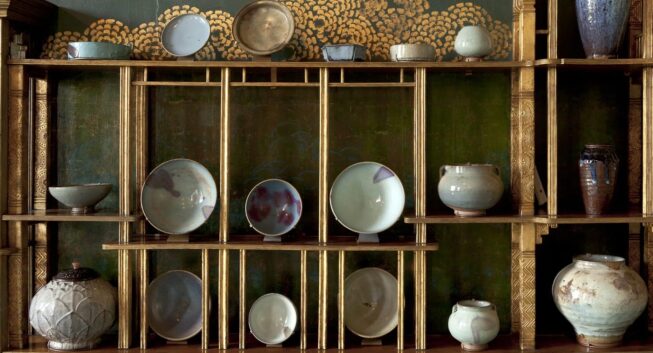

Ruffled Feathers: Creating Whistler’s Peacock Room

July 13, 2024–January 31, 2027

-

The Peacock Room Comes to America

September 3, 2022–ongoing

-

Freer’s Global Network: Artists, Collectors, and Dealers

October 15, 2022–ongoing

Blossom Time (detail), Willard Metcalf (1858–1925), United States, 1910, oil on canvas, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Freer Gallery of Art Collection, Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1915.27a-b

- Jump To...