March 29, 2014–July 27, 2014

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

Japanese Art

On September 3, 1868, the city called Edo ceased to exist. Renamed Tokyo (“Eastern Capital”) by Japan’s new rulers, the city became the primary experiment in a national drive toward modernization. Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915), a minor retainer of the recently deposed shogun, followed his master into exile. When he returned to his birthplace in 1874, Kiyochika found Tokyo filled with railroads, steamships, gaslights, telegraph lines, and large brick buildings—never-before-seen entities that were now ingrained in the cityscape.

Self-trained as an artist, Kiyochika set out to record his views of Tokyo. A devastating fire engulfed the city in 1881 and effectively ended the project, but the ninety-three prints he had completed were unlike anything previously produced by a Japanese artist. Avoiding the colorful and celebratory cityscapes of traditional woodblock prints, Kiyochika focused on light and its effects. Dawn, dusk, and night were his primary moments of observation, and his subjects—both old and new—are veiled in sharply angled light, shadows, and darkness. To accommodate this new way of seeing, Kiyochika effectively invented a visual vocabulary that incorporated elements of oil painting, copperplate printing, and photography. Interest in Kiyochika’s prints revived in the 1910s, when Tokyo intellectuals began to interpret the series as a critique of modernity.

In the exhibition, approximately half of the prints from the Kiyochika’s views of Tokyo are displayed in thematic groupings that represent the artist’s unique visions and site selections. Beyond describing the odd juxtapositions of traditional and modern, Kiyochika lingers on more subtle shifts in communal sensibility. He shows a population inclined to spectatorship over participation and introduces solitary figures sleepwalking in a new landscape.

Gallery

Night Stalls at Asakusa

The myriad shops that lined the approach to the Asakusa Temple constituted one of Edo’s oldest and most popular shopping arcades. Previously depicted by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) and other traditional designers from a bird’s-eye perspective, Kiyochika’s view of the nighttime throng is that of a slightly detached participant.

New forms of lighting technology, including the supernatural glow of carbide lamps, emerge from the center of the market’s activity and command the scene by defining the night and its spectators. Individuals, whether depicted in silhouette or seemingly mesmerized by light, have lost the animated postures of engagement typically seen in market transactions; instead, they stand transfixed.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 1 of 42

Fireworks at Ike-no-Hata

Spectators climb a willow tree to get a better view of fireworks from the edge of Shinobazu Pond in Ueno. Kiyochika makes a visual pun, juxtaposing the tree’s branches with cascading ribbons of light known in fireworks parlance as “the weeping willow.” While Edo-period fireworks had been monochrome, the slow-falling trail of sparks shown here is tinted with color, pyrotechnically made possible in the Meiji era with the use of imported chemicals. Silhouetted spectators lining the bank and in the tree frame the object of attention.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 2 of 42

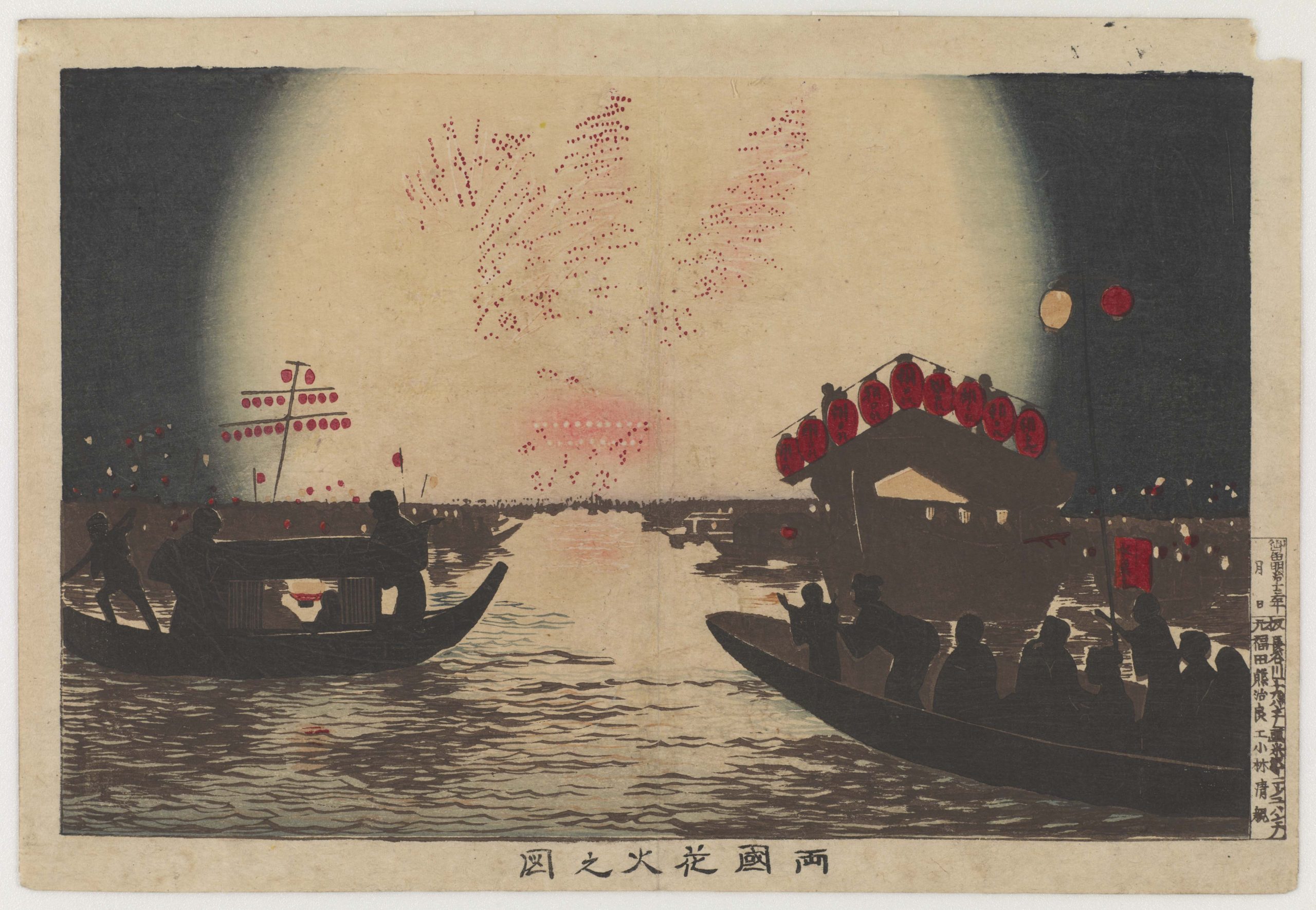

Fireworks at Ryōgoku

The buoyant atmosphere of spectacles at night is captured in this scene depicting fireworks at the Ryōgoku Bridge. A variety of pleasure boats is shown, from open-roof to covered ones for private hire. A fruit vendor peddles “water sweets” at this popular summer attraction.

The vantage point is at water level. Kiyochika enhances the realism of this perspective by focusing on the theatrical animation of spectators in the foreground. The figures are shown in silhouette, marveling at the spherical halo of light. The rippled surface of the water, illuminated by the fiery explosion, appears as an almost photographic rendering.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 3 of 42

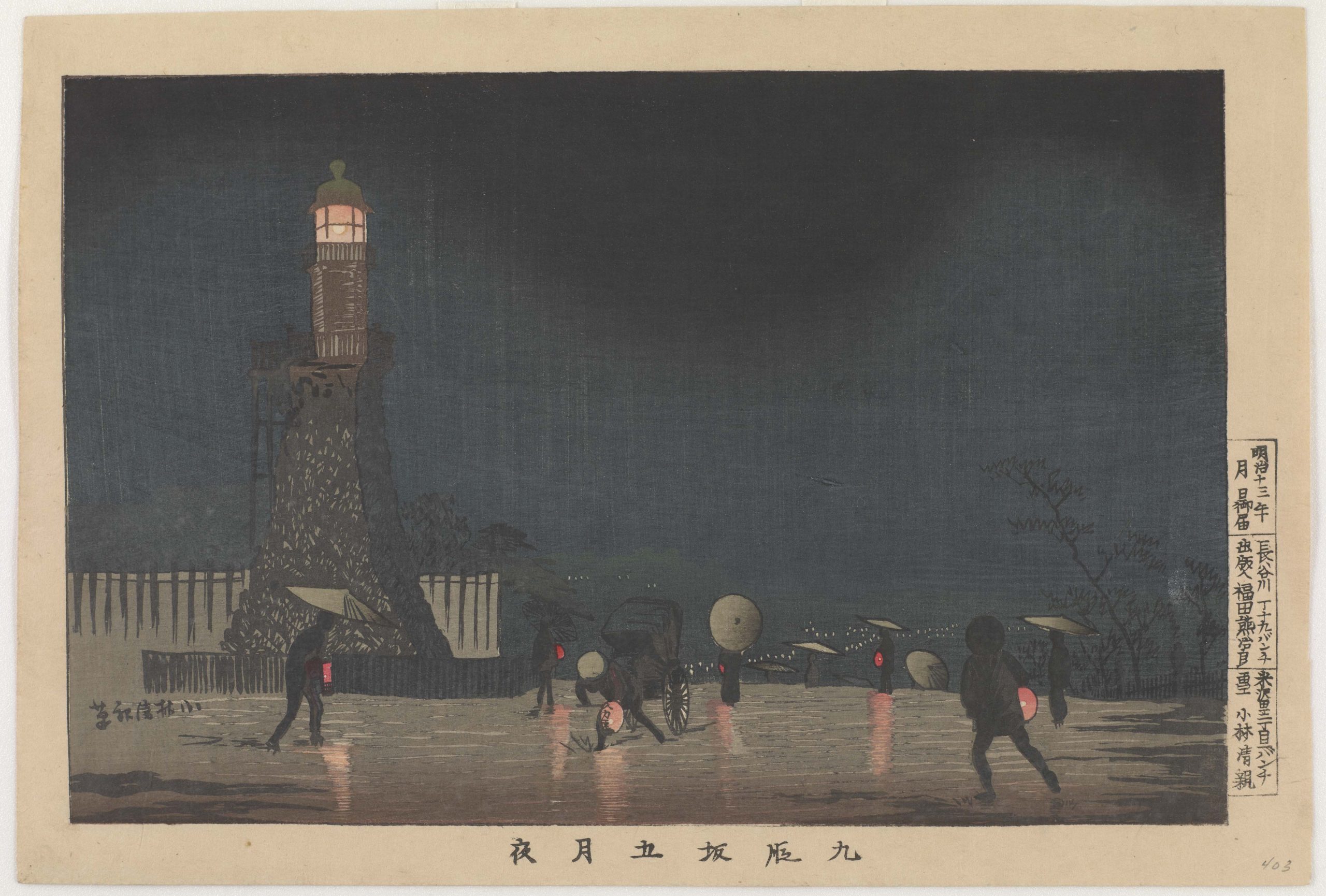

Kudanzaka at Night in Early Summer

With the establishment of Yasukuni Shrine in Kudanzaka in 1869, the site became a landmark as a memorial to Japanese fallen soldiers. The adjoining Western-style lighthouse, constructed purportedly to appease the souls of those who had died bringing about the Meiji Restoration, also guided ships in Shinagawa Bay. In his novella Black Hair, Meiji-era writer Izumi Kyōka (1873–1939) notably feminized the structure, likening the stone base to the fall of a woman’s kimono.

Kiyochika achieved this print’s rich nuances of dark sky with the bokashi technique. He rendered hues ranging from light to dark by applying pigment in a gradient to a moistened woodblock. The standard process of inking the whole block with a single pigment value was much more efficient, but the effect was less subtle.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 4 of 42

Rainy Night at Yanagiwara

The neighborhood of Yanagiwara takes its name from willow trees lining a stretch of the south bank of Kanda River. Barely visible in the far distance at left is a faux-Western/Japanese hybrid building identified as the Tax Bureau Office. Obstructing the view is a covered rickshaw and a cabby captured mid-gesture as he calls to clients. Only a stray dog takes notice.

Kiyochika created a number of impressions for this design, evidencing his experimentation with tonalities. Night is not simply rendered in the classic raven-wing black but expressed as a subtle array of grey, dark blue, and greenish hues. In one impression, diagonal streaks of silver mica have been added, presenting a more overt representation of night rain.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 5 of 42

Shinbashi Station

Japan’s first railway line was inaugurated in 1872 amidst much fanfare. While the Renaissance-style station in Tokyo was celebrated in countless kaika-e (enlightenment pictures), here it appears to sink back into shadows. Kiyochika seems more interested in describing how light flooding from the structure’s interior is refracted on the rain-soaked ground and the glistening, shimmering aspect of the wet surface. At the foreground of this picture is the complex play of station lights, lantern lights, and light diffused through oil-coated paper umbrellas. The resulting polyphony of luminosities is one of the most masterful in his entire series.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 6 of 42

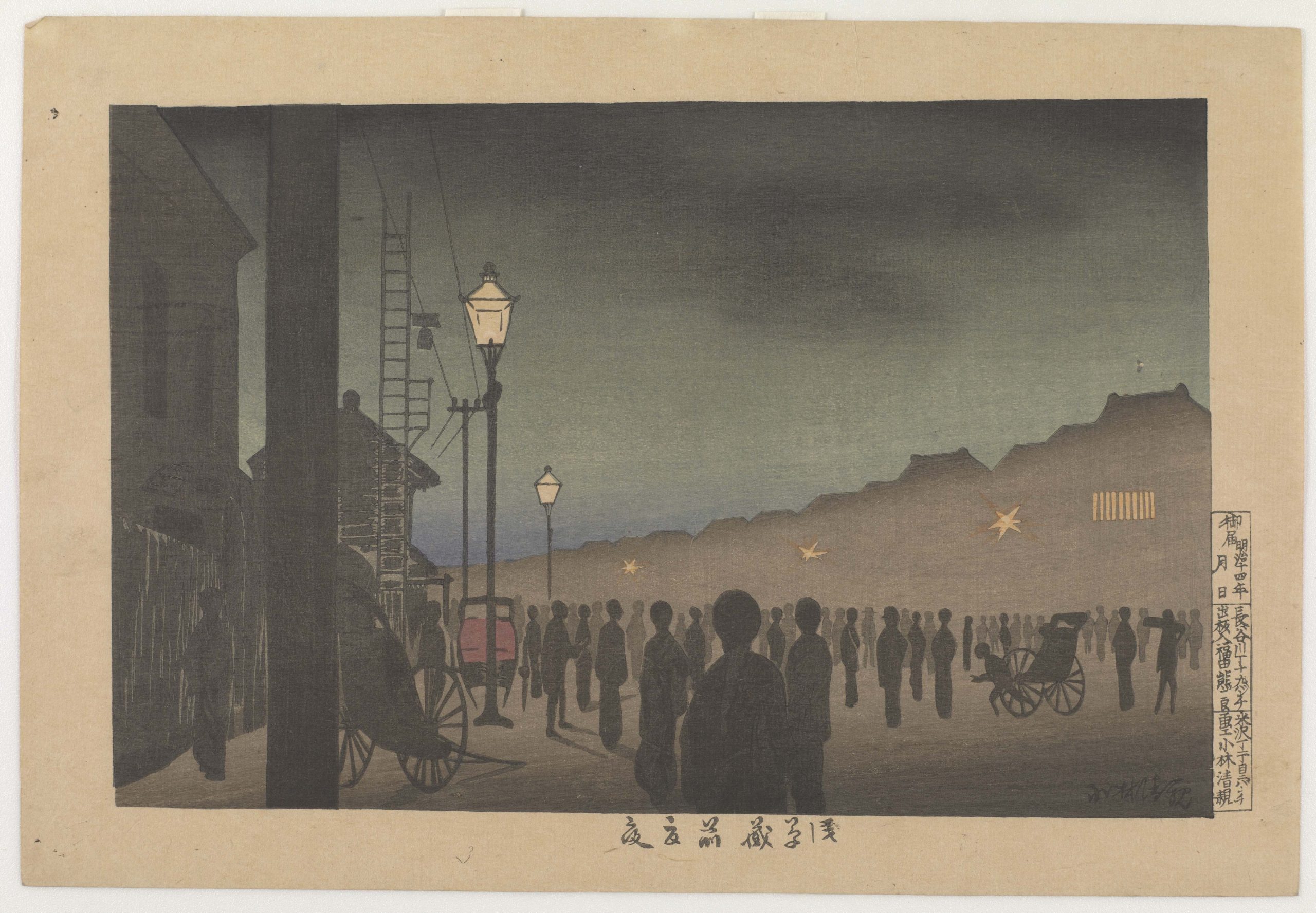

Summer Night at Asakusa Kuramae

The setting of this print is north of Asakusa Bridge, the former location of shogunal rice granaries at which Kiyochika’s maternal family had been employed. The artist returned to this place of his childhood at dusk, during the magic hour when streetlamps were lit one by one. Tonal gradations from sooty grey to blue to purple express the gradually darkening sky with traces of lingering daylight. Silhouetted figures of pedestrians are black and defined in the foreground, soft grey and barely visible in distance, thus evoking the breadth of the newly widened boulevard. The regular spacing of streetlamps on the far side of the thoroughfare is discerned only by star-shaped emissions of light.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 7 of 42

Night at Nihonbashi

Nihonbashi was Tokyo’s commercial center. It also was the first of fifty-three stations of the Tōkaidō, a major artery connecting Edo to Kyoto. Traditional print representations of the site included symbols of power, prosperity, and divine protection—a castle, a fish market, and Mount Fuji, respectively. However, these motifs are absent from Kiyochika’s composition.

Instead, the artist focuses on capturing the moody ambiance of a gas-lit metropolis. Wrapped in the purplish haze of new artificial light, people strolling through the city take on a ghost-like appearance. Landmark buildings are indistinguishable in the shadows, heightening the sense of disorientation. A year after this print was created, the horse-drawn carriage seen proceeding down the sectioned-off center would be superseded by trolley cars.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 8 of 42

Mount Fuji from Edobashi at Dusk

With Tokyo’s first gasworks, which began operating in 1874, the streetlamp joined telegraph wires and the ubiquitous rickshaw as a marker of new technology on the urban landscape. In this work, the gas lamp is a prominent framing device, though partially obstructed by a pine tree. Oil torches line the embankment, their flickering open flames contrasted with the enclosed and steady stream of gas.

The vantage point is from Edobashi, a bridge crossing the Nihonbashi River, which recently had been rebuilt in stone. Nihonbashi, visible in the far distance, was built in wood, albeit in the Western style. Shown in vague silhouette behind it are Mount Fuji and a towering cumulonimbus cloud.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1879

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 9 of 42

Kanda Myōjin Shrine

In this carefully composed scene, Kiyochika achieves a powerful, almost photographic sense of spatial depth. He contrasts shadow and density with the impending rise of the morning sun. Two small figures survey the city’s rooftops on the horizon. The figure on the right is the recurring “man in the hat.”

Kanda Myōjin was the patron shrine for the citizens of Edo. It was associated with the watchful spirit of the warrior Taira no Masakado, who died in 940 seeking autonomy from the central government in Kyoto. Masakado embodied the historic tensions between the increasingly powerful eastern city and Kyoto."

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 10 of 42

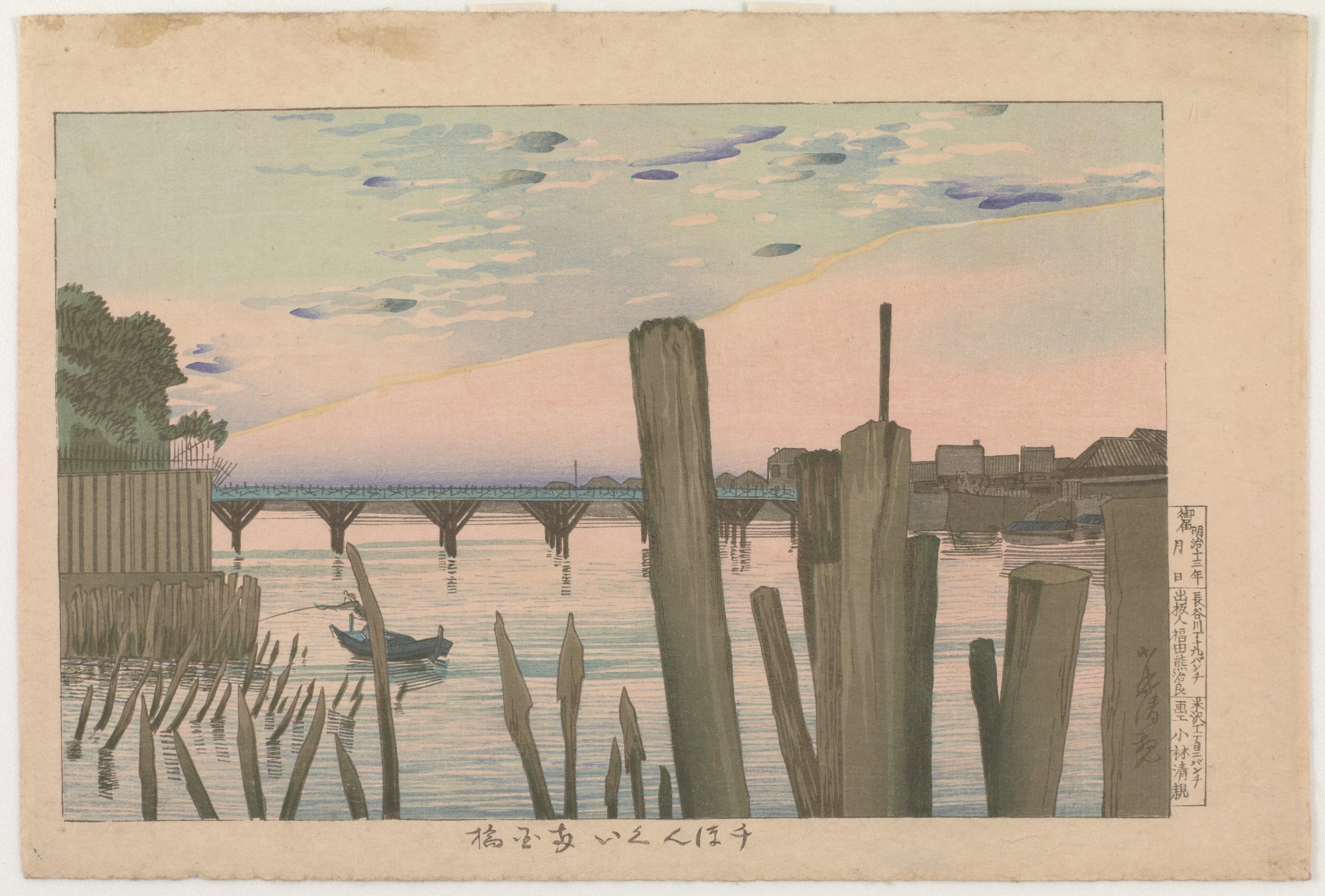

Ryōgokubashi Viewed from Senbongui

The view provided in this print reveals the outline of the great Ryōgoku Bridge to the south. The lone fisherman casts in the area where saltwater and freshwater mix. These abundant fishing waters were especially noted for the giant carp prized in Edo cuisine.

In the distant sky, Kiyochika delineates two states of atmosphere separated by a thin yellow ray. In the west, the colors range from clear to burnt pink; in the east, patchy clouds float against a light blue sky. A similar chromatic is reflected on the water’s surface. This spectrum suggests the time between sunset and nightfall.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, ca. 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 11 of 42

Along Shinobazu Pond in the Rain

The vantage point in this print is from the south shore of Shinobazu Pond at Ueno Park, with a view of Benten Shrine in the distance. The site was a favored subject for early practitioners of Western-style art in Japan, notably Takahashi Yuichi (1828–1894), who exhibited the oil painting Evening View of Shinobazu Pond in 1880. Kiyochika’s signature, scribbled out horizontally, hints at his desire to emulate Western styles. A close-up look at the profusion of lotus flowers shows an almost Impressionist expression of colors, freed of reliance on line and contour. For the key-block outline, Kiyochika employed softer brown instead of black—a striking departure from the norm of traditional woodblock printing.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, ca. 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 12 of 42

View from the Former Yushima Seidō

Originally a private school housed in the residence of neo-Confucian scholar Hayashi Razan (1583–1657), Yushima Seidō during the Edo period became the official training academy for Tokugawa samurai. During the Meiji era, the school shared its premises with the Ministry of Education, Tokyo College for Teachers, and Japan’s first state-run women’s college for teachers, earning its appellation as the “birthplace of public school education.”

In Kiyochika’s print, the venerable site of learning is obscured behind woods. He offers a prosaic view from atop the slope leading down to the Kanda River. The double arches of Yorozubashi Bridge, nicknamed “four eyes,” are visible from afar. The telegraph wires lead the viewer’s eye to the far distance.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1879

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 13 of 42

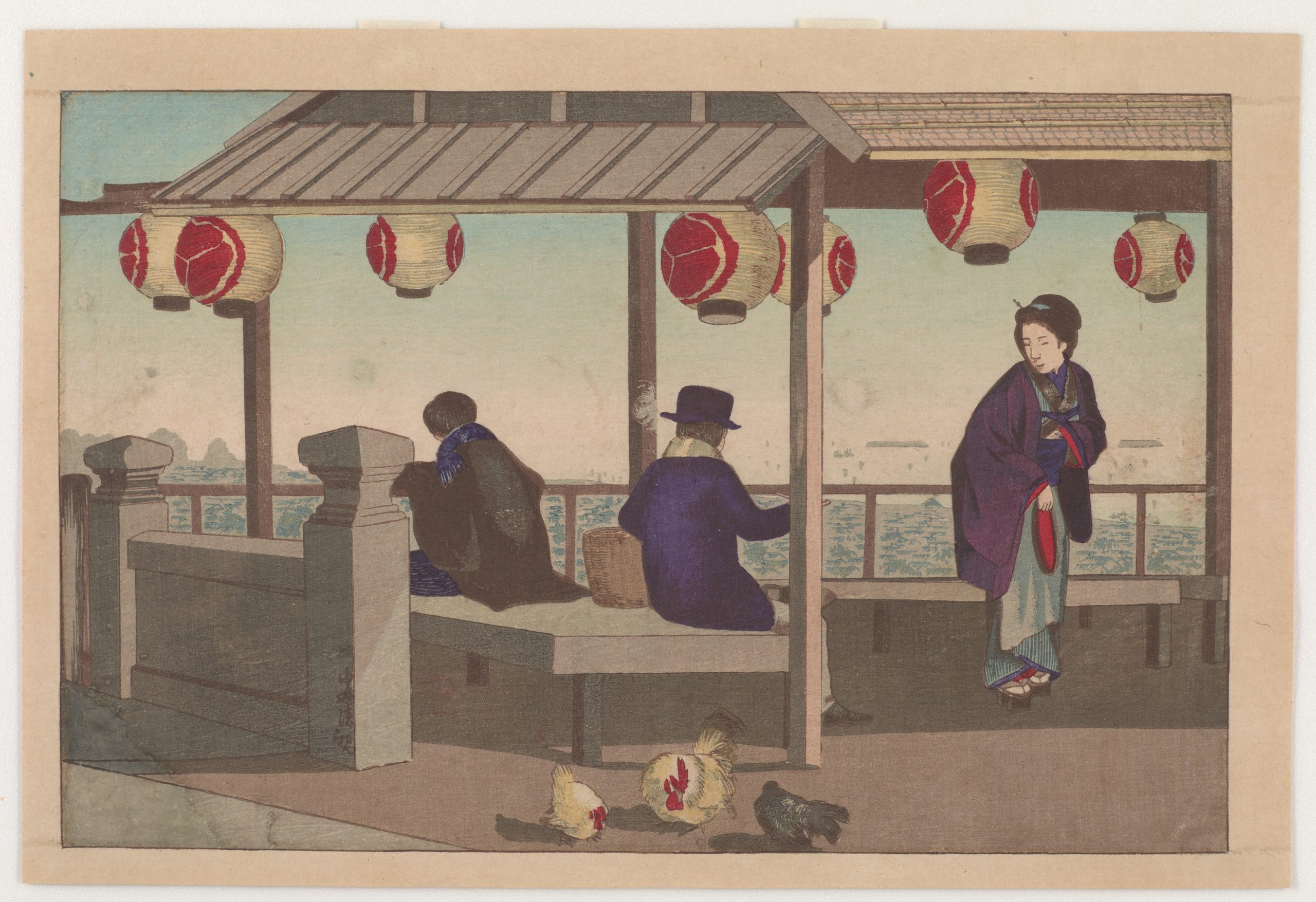

Atagoyama

Atop Atago Hill, the city’s highest natural elevation, two men relax in a teahouse. One wears traditional kimono; the other is in Western clothes. The latter, with his hat, tobacco, and shopping basket, resembles the flâneur look Kafū adopted when he set forth on his city wanderings.

Close inspection of the print (for example, around the cloud of smoke emitting from the Western-style figure) shows areas of mesh-like patterns, similar to cross-hatchings used in copperplate lithography. In addition, the waitress’s red and purple accents may have been inspired by hand-tinted photography. Such experimentations attest to Kiyochika’s voracious interest in the variety of new visual media that were just beginning to emerge in Japan.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1878

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 14 of 42

Paper Money Bureau at Tokiwabashi

The Shiheiryō (Paper Money Bureau) was established in 1871. As demand grew for domestically produced paper currency, the bureau sought to expand its scope of work to include the design and printing of banknotes, securities, and postage stamps. To this end, Italian engraver Edoardo Chiossone (1833–1898) was recruited to implement Western technologies of ink printing on watermarked paper.

The bureau was housed in a two-story redbrick factory building with a phoenix crown, popularly known as Asahikaku (Pavilion of the Rising Sun). In this representation of the building, Kiyochika rendered the dawning sky in pinkish tones. In another, later print, he depicted the scene in broad daylight.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 15 of 42

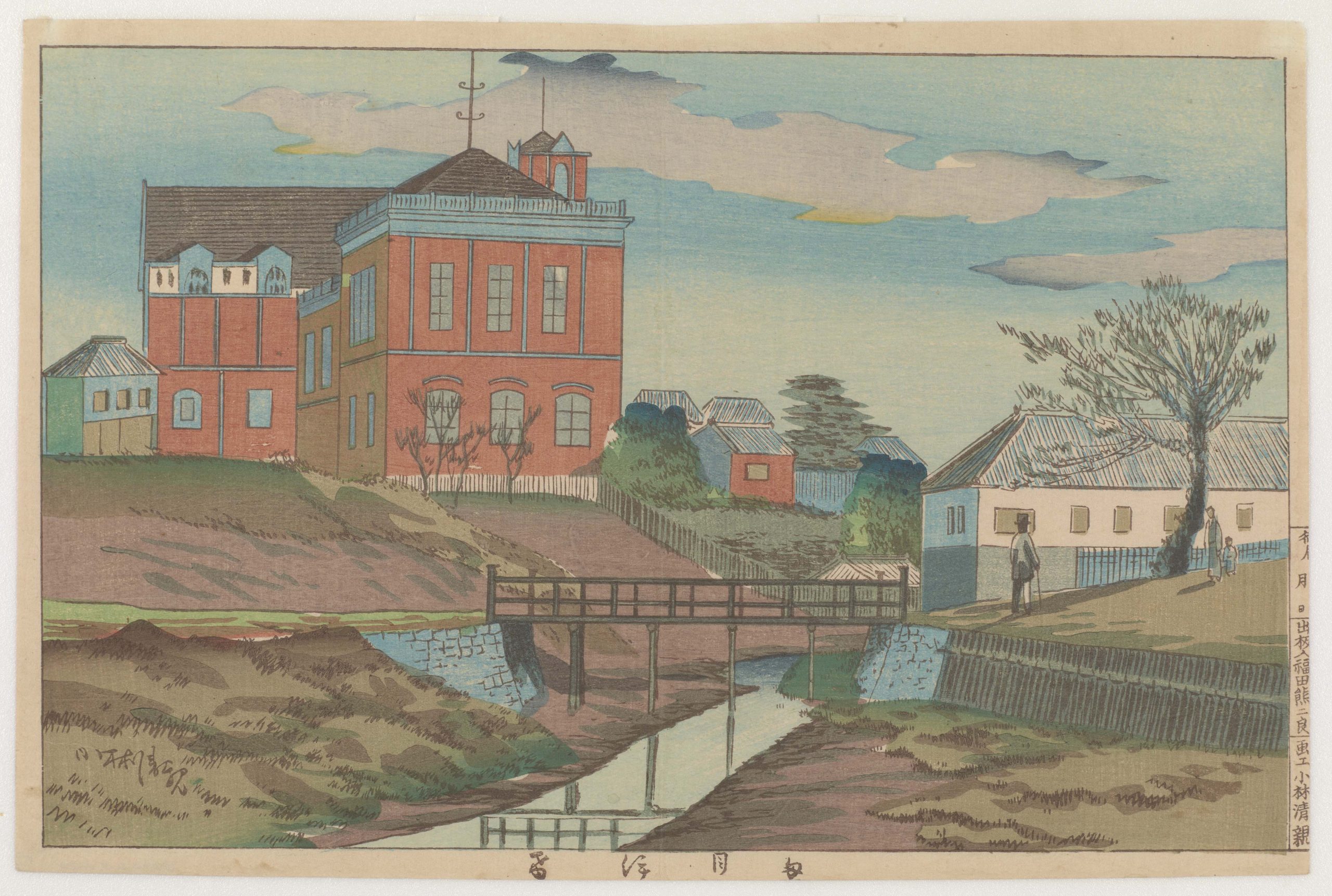

Sunrise at Yorozubashi

Nicknamed “four eyes” for the way its double arches reflected on the water, Yorozubashi was Tokyo’s first stone bridge, built across the Kanda River in 1873. The bridge was adjacent to the Tax Office Bureau, a structure built in the faux-Western, hybrid Japanese style called giyofū. The composite scene was frequently represented as a kaika-e or “enlightenment picture,” which often depicted attractions in garish tones with a cartoonish atmosphere.

Kiyochika’s view presents a startling contrast to this style. It is daybreak, at the hour when people and buildings are just becoming distinguishable in the light. The workday has yet to fully commence; the riverbank appears deserted and empty. An unfinished lamppost and just-planted trees give off the air of a city still in the process of defining itself.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 16 of 42

Tameike

A man in a silk top hat carrying a walking stick is about to cross a bridge. Known as Tameike, this site during the Edo period was a destination that afforded a famous view in the city and featured a picturesque, stream-fed pond. In Kiyochika’s print, recent construction of the surrounding buildings has diminished the large body of water to a trickle.

On a hill behind the bridge is Japan’s first official school of fine arts, which opened in 1876 as a division of the College of Engineering. The man might represent Italian artist Antonio Fontanesi (1818–1882), whom the school hired for a brief period to teach techniques of Western-style oil painting. Kiyochika, on the other hand, was largely self-taught and remained outside the academic system. This somewhat wistful view perhaps reflects a certain longing on the part of the woodblock artist.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 17 of 42

Museum Fountain at the Second Domestic Exposition

Japan’s advances in craft and industry were profiled in government-sponsored exhibitions. The odd configuration surmounting the fountain in the foreground of this print is a temporary replication of a scene from the Noh play Shōjō. In it, monkey-like creatures reel, inebriated from drinking from a bottomless jug. Suggesting his commitment to realistic representations, Kiyochika apologizes in a note to the right, stating that the “disproportionately large fountain figures were drawn in accordance with the publisher’s wishes.”

Behind the fountain is the dome-topped, redbrick Ueno Museum. British architect Josiah Conder (1852–1920) designed the museum, one of many notable structures erected during his long tenure in Japan (1877–1920).

Remarkably, only thirteen years before Kiyochika created this print, this area was the site of the final pitched battle between the imperial restorationists and the shogun’s forces.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 18 of 42

Suspension Bridge within Castle Grounds

Tokyo’s first suspension bridge was designed by the Irish-born engineer Thomas Waters (1842–1898), one of the many “foreigners for hire,” or resident foreign advisors working for the Meiji government.

Kiyochika depicts the redbrick and stucco structure with wire cables and steel braces, the pillar beam adorned with the imperial chrysanthemum crest. The man-and-horse bridge crossed a private moat within the grounds of the Imperial Palace, and in fact was closed to the public. Kiyochika likely relied on photographs to create his design. The couple shown to the left marks one of the few instances that he included Westerners in his Tokyo views.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, ca. 1879

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 19 of 42

Waterworks at Nakasu on the Sumida River

Kiyochika’s interest in the novel creations of his time permeates many prints in his unfinished series. The word “torpedo” (suiraika) had only appeared in 1880 or 1881 in new weaponry lexicons. These weapons would not be employed in hostile action for more than a dozen years.

In this print, the mood is one of celebratory naiveté. Spectators view the massive spray of water as if it were a kind of daytime firework display. The island obscures the view of the actual destructive impact. Kiyochika’s technical prowess in representing an explosion during the day as a white geyser under the grey sky contrasts with the intense green covering the island and the costumes of the passers-by.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 20 of 42

Moonlit Sea at Kawasaki

Kiyochika again creates an imaginary scene in this print, one likely inspired by another Currier & Ives lithograph. The point of view here is ambiguous, but it presumably suggests that Japanese people are observing foreign battleships in a firing exercise, held in Tokyo Bay off of Kawasaki to the south of Tokyo. The print is an essay on light—Kiyochika’s mix of natural moonlight and the violent bursts emitted from these dark and relatively unfamiliar hulks.

This image is prescient. Later in his career, Kiyochika would produce woodblock print accounts of two of Japan’s expansionist wars with China (1894–95) and Russia (1904–5). In each instance, Kiyochika relied on reports from the front to create imagined dramatic scenes of both land battles and engagements on the high seas.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, ca. 1879

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 21 of 42

View of Umayabashi

In 1874, the Umaya Bridge was built over the Sumida River, connecting the areas of Kuramae and Komagata on the western bank and Honjo on the eastern bank. This bridge was one of the first modern infrastructures constructed in the reign of the Meiji emperor. Umaya means “horse stables” and refers the shogun’s stables, which were once located near the bridge’s western end.

The scene described here is a torrential storm. Pedestrians scurry under lashing rain. Kiyochika contrasts poles that uphold telegraph wires with the ominous force of the storm.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 22 of 42

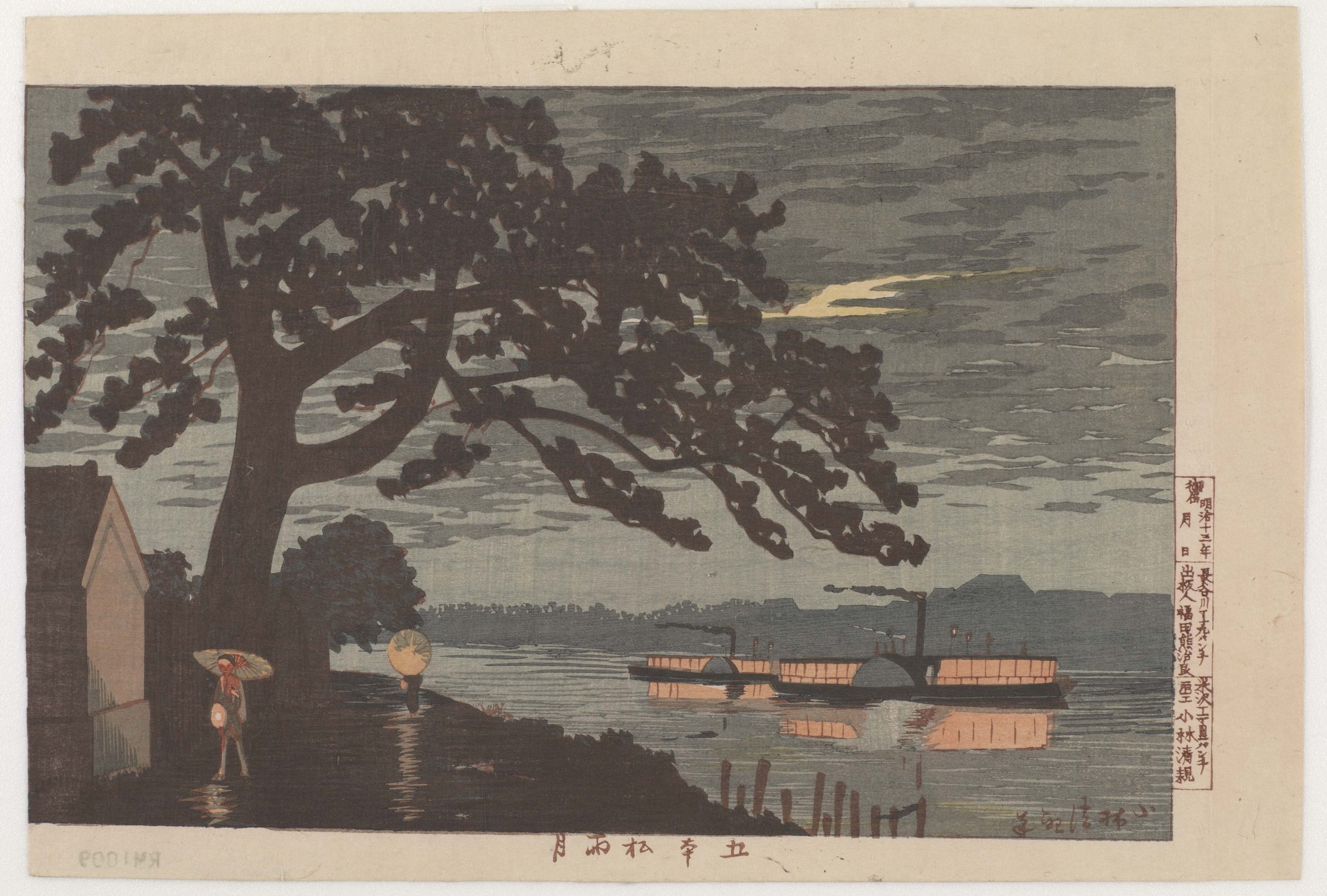

Rainy Moon at Gohonmatsu

The Japanese language first accommodated the concept of “steamboat” in 1853. Here, Kiyochika establishes contrasts between the figures who stroll along the bank carrying traditional lanterns and umbrellas and the sleek steamboat slicing through the canal. Light reflected on the rain-dampened path and on the river are two irresistible points of observation for the artist.

Gohonmatsu (five pines), an auspicious bend on the Onigawara Canal in Edo, was named for five auspicious pines. The trees grew on the estate of Baron Kuki Ryūichi (1852–1931), keeper of the imperial art collections and a prominent art collector who had significant interactions with Westerners. By Kiyochika’s time, only one tree remained, but it still encapsulated the pine’s essential meaning of longevity.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 23 of 42

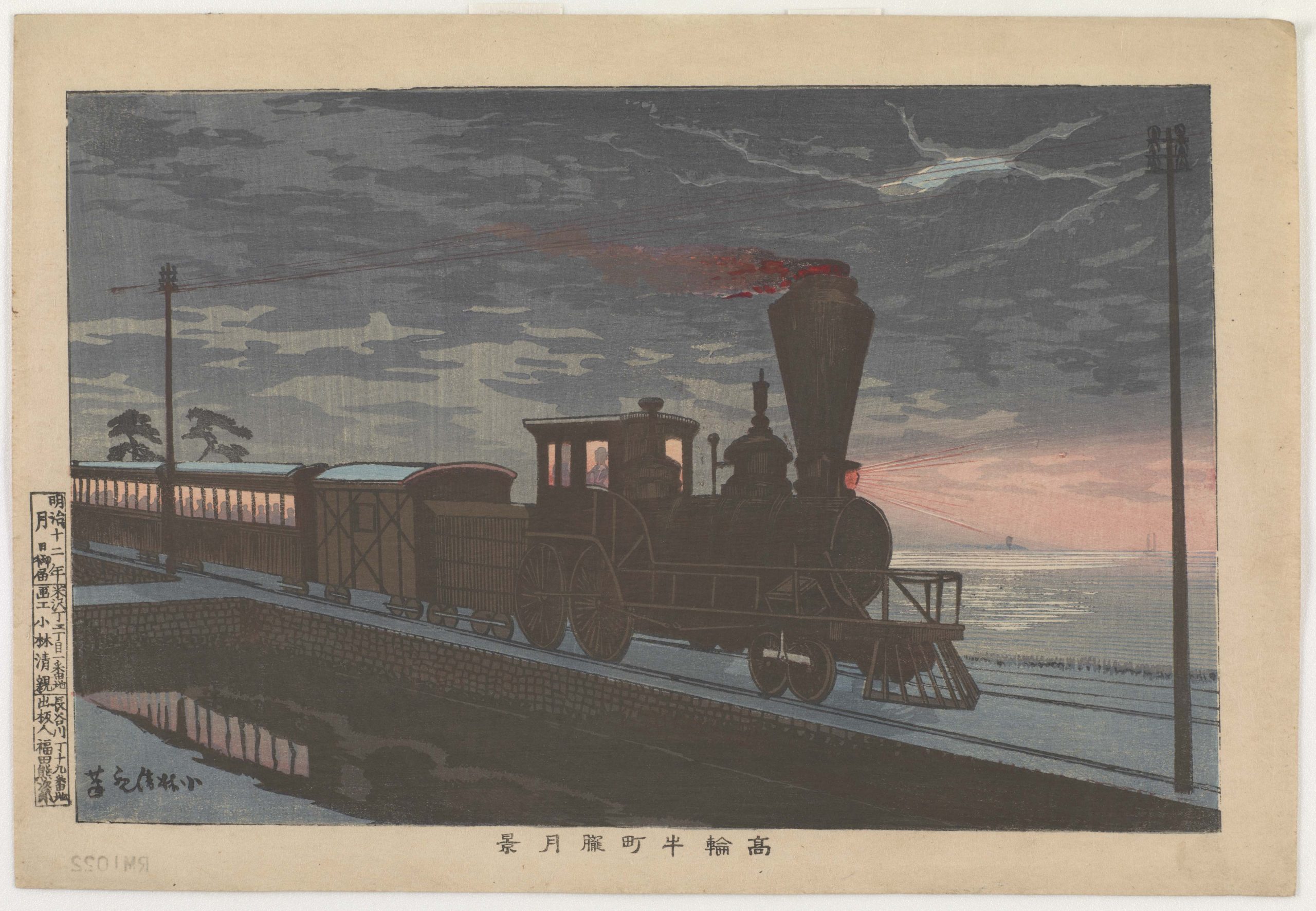

View of Takanawa Ushimachi, under a Shrouded Moon

Kiyochika made this print in 1879, seven years after a rail line opened to connect Shinbashi in central Tokyo with Takanawa, about four miles down the coast of the bay. However, it seems that Kiyochika was depicting a type of locomotive that had yet to make its appearance in Japan. In anticipation, he borrowed liberally from a Currier & Ives lithograph of the engine.

This study of light—perhaps Kiyochika’s most highly regarded—posits the train as the vehicle of modernity; it belches controlled fire and casts transforming rays from its headlamp, cabin, and carriage. The illumination provided by the dramatic, shifting, and grandly unpredictable sky contrasts with the modern light. Passengers in this journey are ghostly silhouettes, a form used again and again by Kiyochika to depict humans in this newly available night.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1879

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 24 of 42

Distant View of Ichinohashi Bridge from Sumida River’s Embankment

When accommodating early Western diplomatic and commercial missions, the Japanese strove for a polite isolation of these still unknown and thoroughly exotic visitors. Ishikawa and Tsukiji, two islands reserved for habitation by foreigners, were in the bay just to the east of Shinbashi, the new Tokyo’s central transportation hub. Ichinohashi Bridge connected the islands. On outings and excursions to the foreign concessions, the Japanese could gawk at the novelty of transplanted Western customs, all the while unwittingly becoming modern.

Kiyochika combines some of his favorite themes in this print: a nocturnal landscape, various sources of light, and silhouettes of characters and buildings. In this nightscape, he subtly associates the pleasures of the old Edo (the geisha) and modern innovations (the rickshaw). He also provides one of the last views of a site that would soon be completely transformed.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 25 of 42

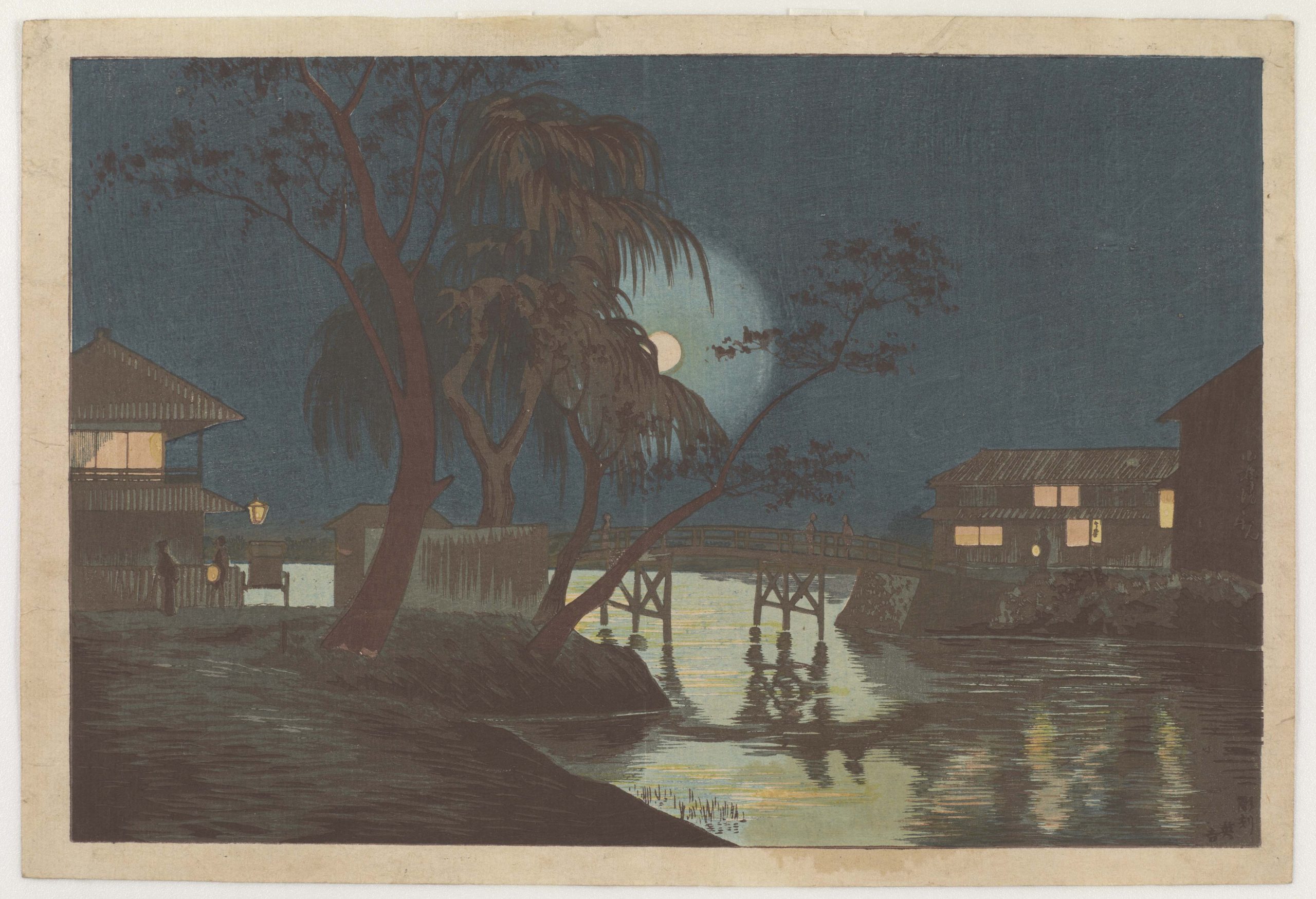

Teahouse at Imadobashi by Moonlight

The Imado Bridge, built over the Sanya Canal, was in its heyday one of the major points of access to the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters. Under the bridge and all around it were landing places for the slender roofless boats that carried Yoshiwara’s visitors. Kiyochika’s print focuses on two teahouses connected by this bridge, though, in the moonlit night, no sign of traffic is observed on the canal. In Kiyochika’s day, Imado was becoming rundown and distant in style and clientele from those of Edo times. This work emphasizes the contrast between the lit interiors of the teahouses and lanterns carried by attendants—the flicker of the past and the anonymity of the new “classless” society.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, ca. 1887

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 26 of 42

Summer Moon at Imado

In a composition that seems unique in the annals of Japanese woodblock-print making, a geisha tunes her shamisen as she prepares for an evening of work. The desired erotic mood, once achieved by moonlight and flickering candles, has been compromised by the light of a kerosene lamp. Her face and figure, which should be veiled in mystery, cast their own shadows beneath the unfamiliar and unforgiving glare. The coloring in this print is reminiscent of the hand-tinted photographs popular in the period.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 27 of 42

View of Yūmeirō Restaurant at Imado

The restaurant depicted here, originally known as Konparō, was destroyed by fire in 1855 and resurrected in Kiyochika’s time as Yūmeirō. The name itself is a pun combining yumeji (path of dreams) and yumeiro (vanity of carnal pleasures). Such an image and suggested title would have appealed to Nagai Kafū’s sensitivity to ephemerality and pleasure.

The composition indicates receding registers of light in an otherwise dark night. On a diagonal from foreground to distance, Kiyochika rendered reflected or cast light, interior lighting, and finally, his trademark: light as a tear in a cloudy sky.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1879

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 28 of 42

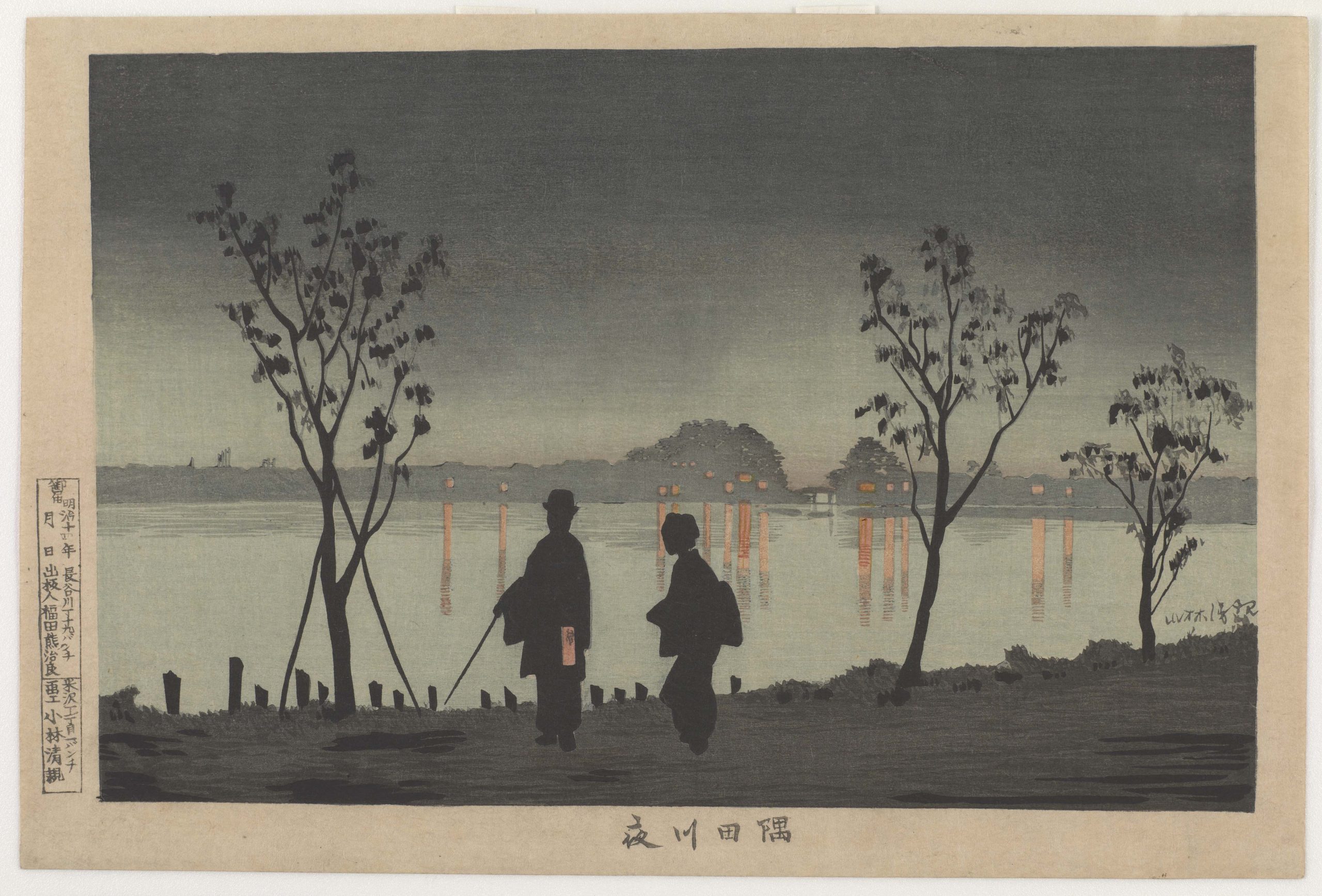

Sumida River by Night

One of Kiyochika’s iconic works, this print is often associated with Nagai Kafū’s 1909 novel Sumidagawa (The Sumida River), in which the protagonists serve as pretexts to write about Tokyo’s vanishing famous sites. In the print, the two characters silhouetted against the night sky are a geisha, with a traditional hairstyle, and her patron, wearing a Western-style hat. The couple stands on the eastern bank of the Sumida River at Mukōjima and looks to the western bank at Asakusa and Imado. The humpbacked bridges in the distance and the reflection of distant lights in the river contrast with the nocturnal sky and its subtle shades of grey and black.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, Meiji era, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 29 of 42

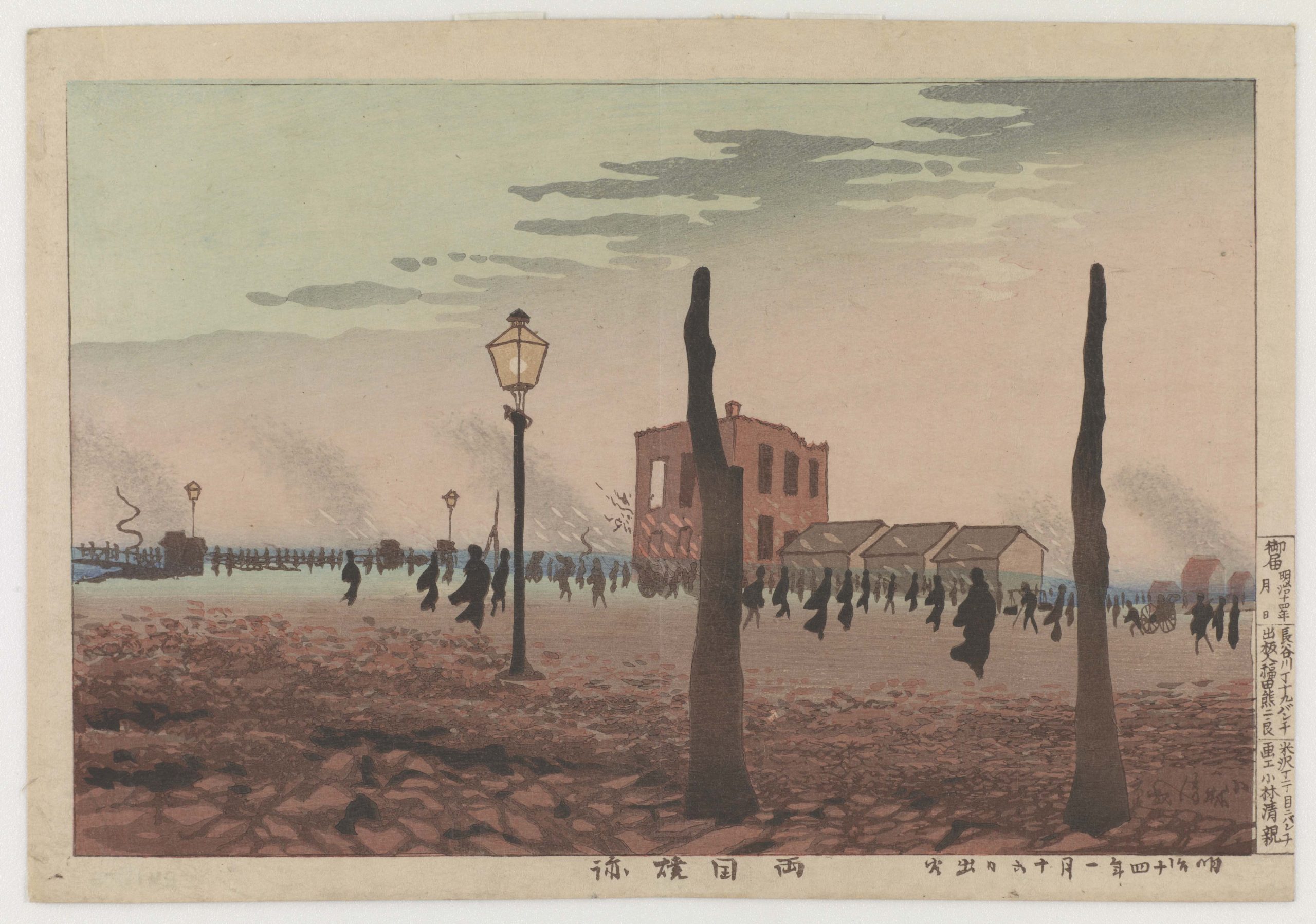

Ryōgoku after the Fire

Few images of devastation match Kiyochika’s rendering of the smoldering aftermath of the Great Ryōgoku Fire. In the foreground, all that remains of the Ryōgoku Police Station are charred posts. In the distance is the burned-out shell of the telegraph office. In the far west horizon, plumes of smoke mark the Kanda area, where the fire originated. Figures move ghostlike through the aftermath, their forms barely distinguishable from the wasted debris.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 30 of 42

Outbreak of Fire Seen from Hisamatsuchō

Kiyochika lived in the Hisamatsu area, located close to Hamachō in the eastern part of Nihonbashi, near the western banks of the Sumida River. The fire of February 11, 1881, did not rival the scale of the Great Ryōgoku Fire, but it nevertheless savaged Kiyochika’s neighborhood. He produced this particular composition in several different impressions with variations in color. Creating dramatic scenes of disaster had an appeal that trumped quieter and more reflective studies of the changing cityscape.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 31 of 42

Great Ryōgoku Fire at Asakusabashi

The Kanda River flows west to east across the northern part of the central city and then joins the Sumida River as it runs south to the bay. The Asaskusa Bridge spanned the Kanda River just before Yanagibashi at that juncture. Kiyochika renders this chaotic fire scene from the north riverbank looking to the southeast. On the far shore, a large structure is being consumed by the flames, suggesting the sheer scale of the fire. In the distance, tiny figures flee across the bridge. Kiyochika captures the true sense of panic in the face of massive disaster.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 32 of 42

Great Fire in Ryōgoku Drawn from Hamachō

The fire of January 26, 1881, is observed from the western bank of the Kanda River, looking north to the flames as they sweep across Ryōgoku Bridge. To design this print, Kiyochika added fire to the composition of a sketch made on a clear day some months earlier. Thus, there is some duplicity when he notes on the print that it was “drawn from nature.” The figures shown in the foreground—observers and those who run in panic—are among the most animated in Kiyochika’s descriptions of the new city.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 33 of 42

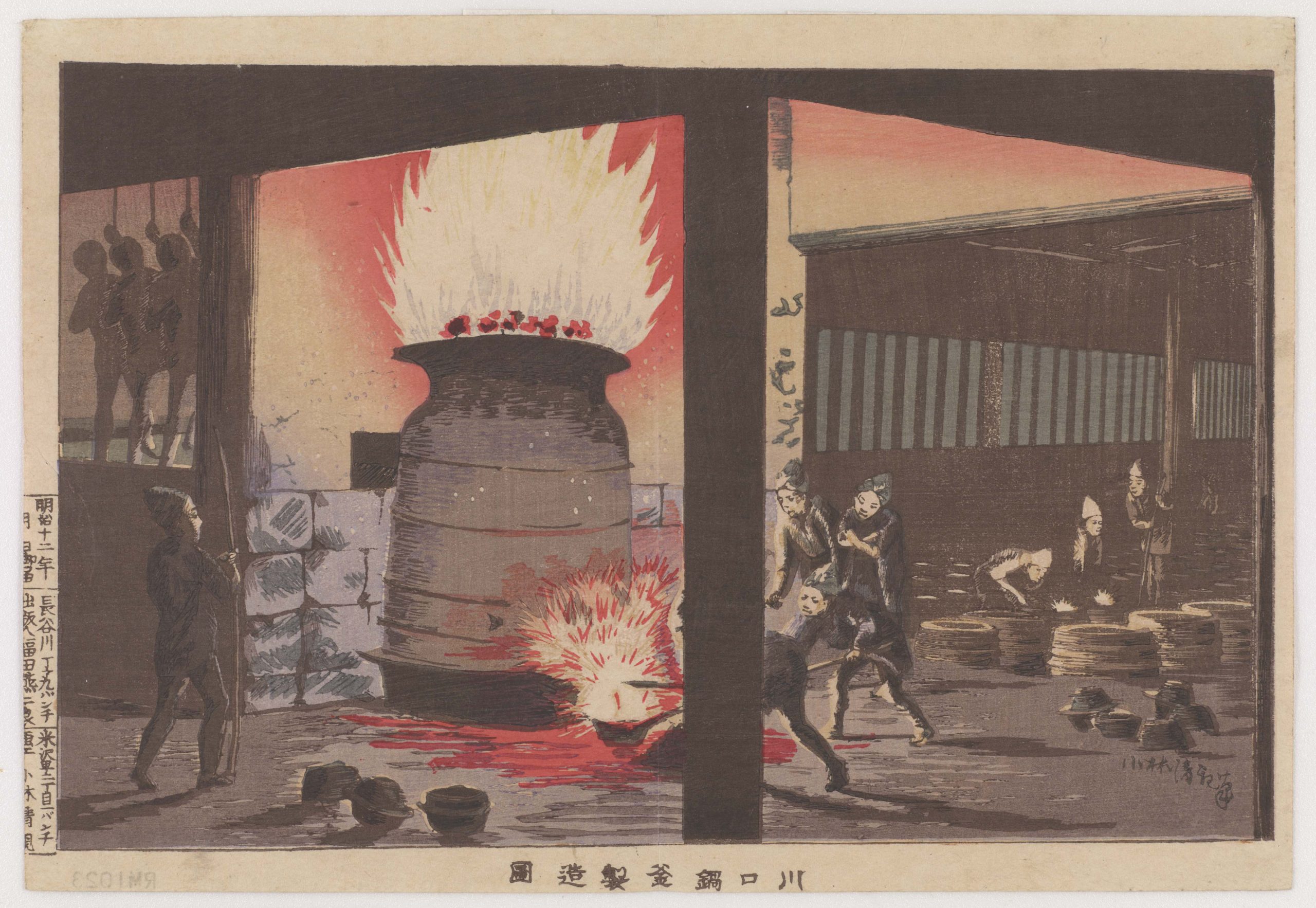

Manufacturing Pots and Kettles in Kawaguchi

The foundry at Kawaguchi, about ten miles north of Tokyo, predated the imported innovations of the Meiji era. This small foundry and its successors would shape the modern Japan. Although depicting a place that manufactured prosaic kitchen utensils, Kiyochika created a strikingly theatrical and portentous sense of inferno with synchronized workers (note the identical silhouettes in the upper left) carrying on into the night. The print forcefully conveys the power inherent in controlled fire.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1879

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 34 of 42

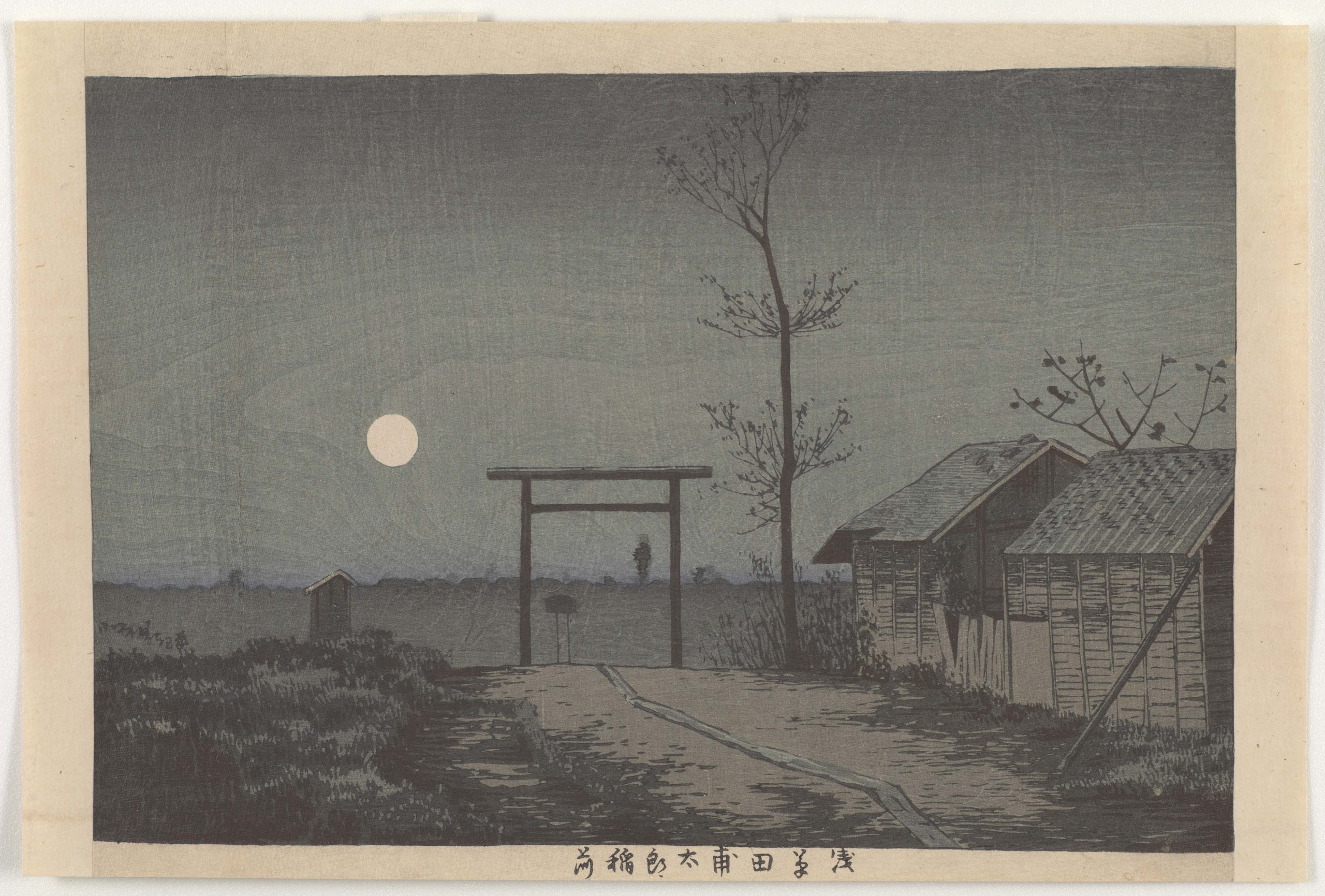

Tarō Inari Shrine at the Asakusa Rice Fields

In Japan, the spirit of Tarō Inari is revered in a vast number of Shinto shrines. Distinguished by vermillion-painted gateways (torii), these sites also have images of foxes (kitsune), usually in male-female pairs. The fox was thought to be an incarnation of the Inari spirit or a messenger to that deity. In addition, the fox, a wily shape-shifter, often was associated with seduction. Thus, Inari shrines were often in close proximity to pleasure quarters.

This print suggests nothing of the gaiety, noise, and color that surrounded an Inari shrine filled with petitioners. Kiyochika’s view is of a deserted shrine near an area of ramshackle brothels known as Asakusa Yoshiwara. The path meanders beyond the gateway to an indeterminate future. One of the last of Kiyochika’s ninety-three images of Tokyo, its sense of haunting desolation permeates the view.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, ca. 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 35 of 42

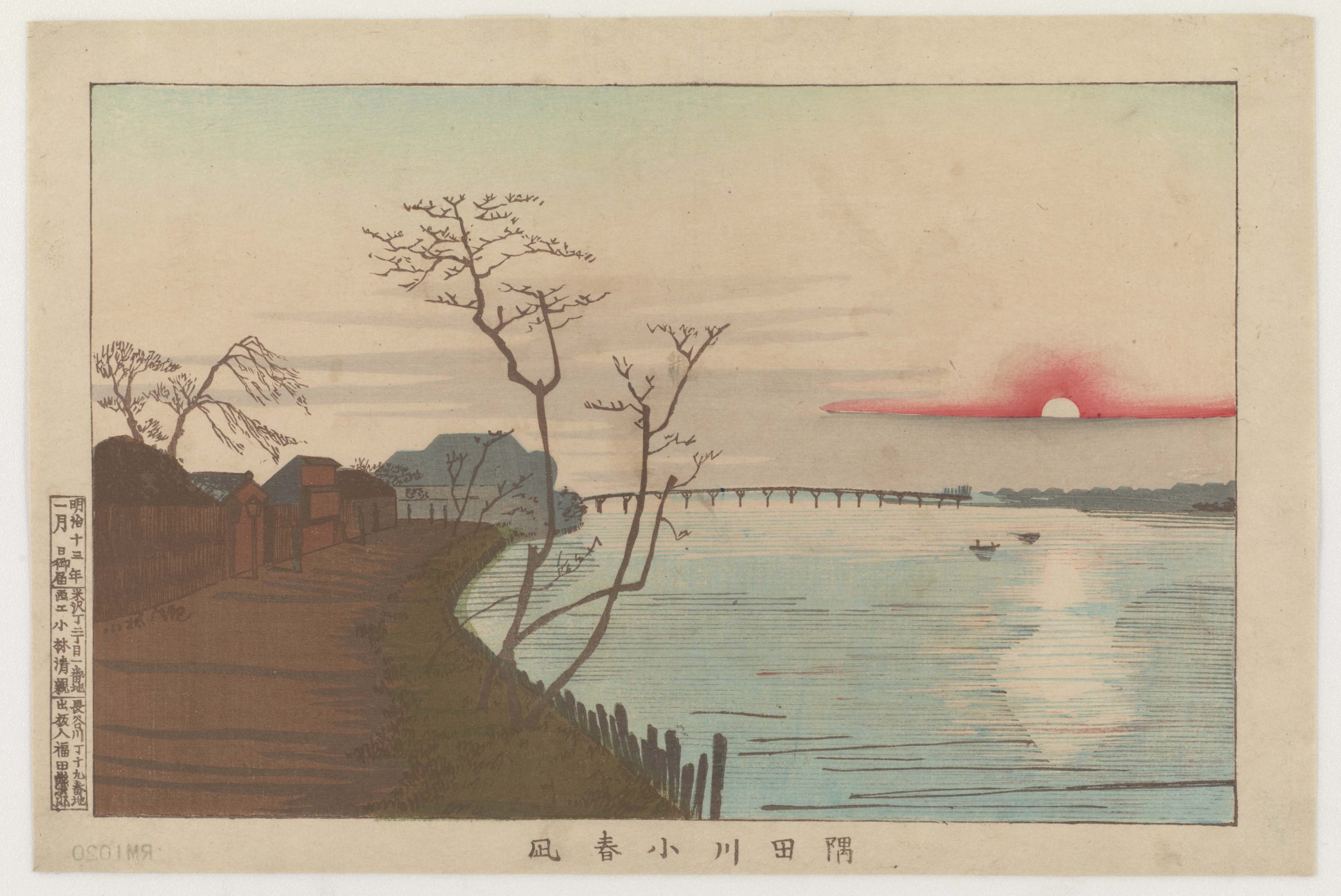

Late Autumn Calm on the Sumida River

As in several of his other prints, here Kiyochika favors a sunset or twilight view of the western horizon from the vantage point of the Honjo neighborhood north of the Ryōgoku Bridge. The Japanese title includes the term koharu or “brief spring,” suggesting a time of particularly favorable weather in an otherwise cold season.

This print belongs to what might be called Kiyochika’s “harmonies in brown,” a technical innovation achieved by applying an ochre pigment tone on the printing block.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 36 of 42

Okurabashi in Honjo

A figure of the modern, well-to-do flâneur looks at two women absorbed by the view of the evening sky and of the other side of the river. This print is one of the most personal among Kiyochika’s views of the new capital. The bridge it represents was located in Honjo, the area of town where Kiyochika was born and where his father had been in charge of opening and unloading the government’s rice granary. During the Meiji era, this part of the city served as the uniform depot for the Japanese army.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 37 of 42

View of Tokyo’s Shin-Ohashi in Rain

A woman’s figure provides an accent of color as she strolls, protected by her umbrella, northward on the eastern bank of the Sumida River. Her kimono is hiked up, revealing a substantial amount of red undergarment. In earlier printings, an English title, View of Rainfall on Shin-ou-hashi in To-kei, is included in the margins, suggesting an interest in capturing a foreign market.

Constructed in 1693, the Shin-Ohashi Bridge was the subject of a famous print by Utagawa Hiroshige. In this depiction, among the first of his ninety-three prints, Kiyochika introduced many themes that he would explore in his views: the interplay of varied light sources, the use of spectrums of greys and purples to convey mood and psychological states, and a persistent interest in bridges and liminal spaces.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1876

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 38 of 42

Distant View of Ryōgokubashi from Motoyanagibashi

Kiyochika’s view of the massive Ryōgoku Bridge is from slightly downstream on the western bank of the Sumida River, where the small bridge called Motoyanagibashi crosses a canal. Here, moto means “former,” referencing the fact that a new Yanagibashi has been constructed further to the north. Central to the composition is a venerable willow tree (yanagi) with a white scar from a lightning shear prominent on its trunk.

Originally constructed in 1659, the iteration of the Ryōgoku Bridge seen in the fog-shrouded distance was completed in 1861. Two figures, a man standing on a pier and a woman near the tree, seem to gaze at the massive structure. Kiyochika casts a mood of pensive uncertainty. Years later, in a 1914 essay on the Japanese woodblock print, the writer Nagai Kafū would interpret this work by Kiyochika as a commentary on the failures of modernization.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1879

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 39 of 42

Koromogawa River at Tennōji-shita

Kiyochika made variant impressions of this design. For some versions, he employed a black outline, standard in traditional woodblock prints, while for others he experimented with a softer brown. The former expresses the inky, cloaking quality of the night’s darkness. The latter creates a warmer, restful atmosphere.

The title of this print alludes to a tributary nestled in the swampy area of Yanaka, in Ueno and near a new museum designed by Josiah Conder. The proximity to the encroaching modern landscape is not evident in this scene, yet the contemporary Japanese viewer would have understood Kiyochika’s suggestion that two distinct worlds coexist under the cover of darkness.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 40 of 42

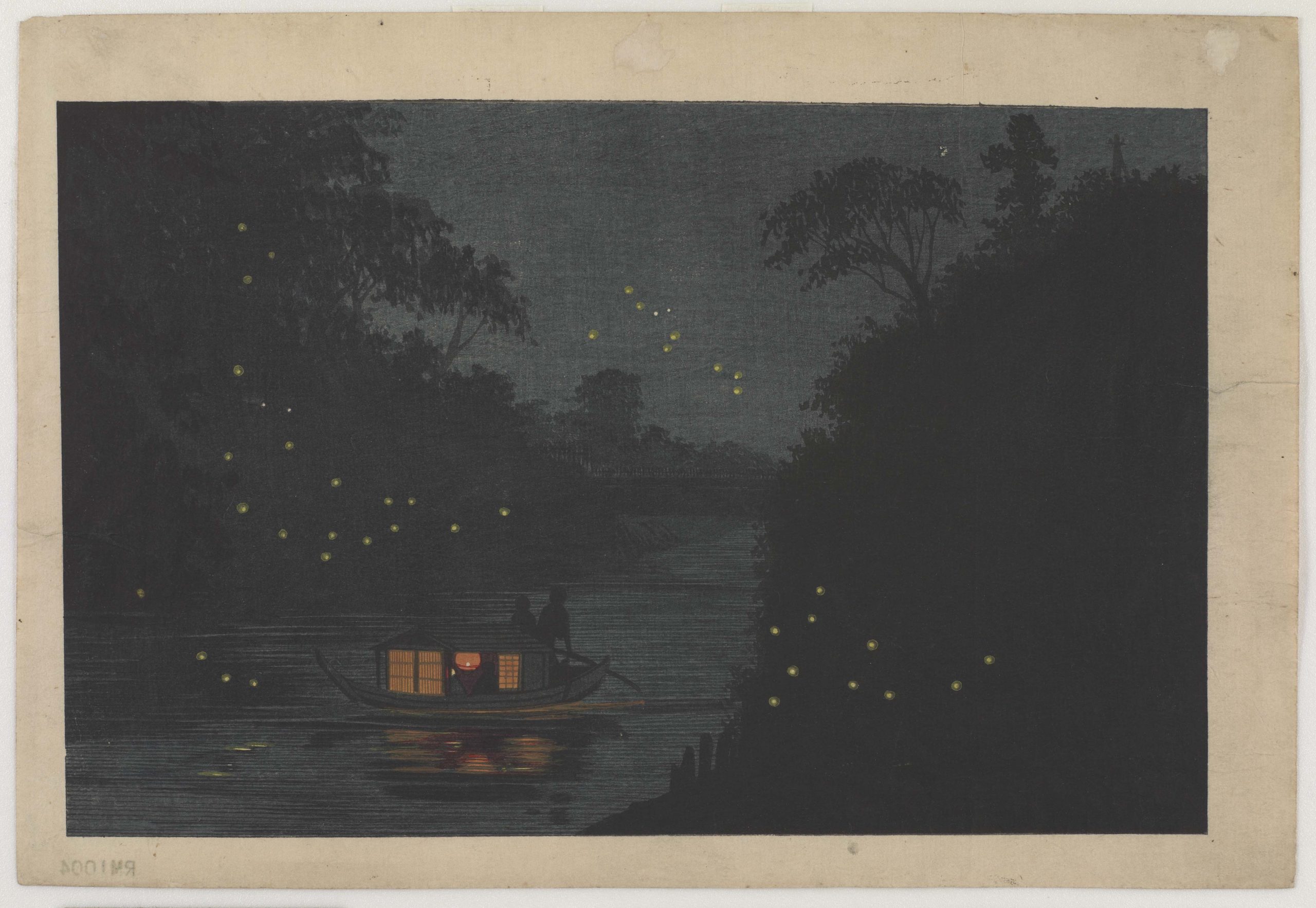

Fireflies at Ochanomizu

A roofed pleasure boat slowly floats down the water at twilight. Despite the summer pastime’s bucolic association, the setting is Kanda River, in the heart of the city. In this composition, Kiyochika employs a vanishing-point perspective and subtle tonal gradations to express the depth of the quickly descending darkness. The delicate glow of fireflies—rendered in two shades of yellow—serves to emphasize the night’s seductive pull. It is interesting to note that the American artist James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), who was fascinated with the “veiling” effect of the evening on the Thames, also used numerous pinpoints of light to structure darkness in his paintings.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1880

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 41 of 42

Year-end Market at Sensōji Temple

The toshi no ichi was a traditional market held toward the end of the year, when the people of Edo would make their annual excursion to purchase decorations and specialty food items for New Year festivities. The turning of old to new is underscored by the juxtaposition of new Meiji-era symbols, such as the telegraph pole, streetlamp, and Western-style building, with more traditional elements, such as street performers, paper lanterns, and temple structures, shown in silhouette.

In Kiyochika’s composition, there is none of the rowdy, rambunctious atmosphere that surrounded the festivals and spectacles of Edo. In spite of the obvious range of activity depicted, the foreground row of silhouetted figures defines the intended perspective; Kiyochika invites the viewer to observe the observers.

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915)

Japan, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

Robert O. Muller Collection

Image 42 of 42

Map

Although Edo was Japan’s de facto center of political power from the early 1600s, Kyoto remained the capital until 1868, when an official transfer to Edo occurred and Edo’s name was changed to Tokyo. This map dates to 1879. Unlike the elegantly proportioned and stately streets of Kyoto, laid out in a classic grid pattern, the new ruling city accommodated a jigsaw puzzle of natural topography. Rivers, streams, and canals emptied into lowlands and estuaries. To the west of the Sumida River, land rose unevenly but steadily to a higher ground.

“High city, low city” was a phrase that defined both topography and social status. There were two focal points in the new Tokyo: the bustling commercial and entertainment areas along the river and, to the west, the parcels of land that grew from the central moated castle. When the shogun-daimyo-samurai societal structure collapsed, so did the reason for and population of that “retainer” culture. The city, high and low, was open to anyone—if not economically, at least for leisure activities and strolling around. Kiyochika’s prints explored new vistas, not with the conventional bird’s-eye view, but from a human eye at a human scale.

Credit for map:

Survey map of Tokyo (1879) from the collection of Edo-Tokyo Museum

Keep Exploring

-

An American in London: Whistler and the Thames

May 3–August 17, 2014

- Jump To...