October 14, 2017–February 6, 2022

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

Across Collections

Buddhism—and the art it inspired—helped shape the cultures of Asia. Today, its extraordinary art is a source of beauty and contemplation for audiences across the world.

Encountering the Buddha brings together more than two hundred artworks, spanning two millennia, to explore Asia’s rich Buddhist heritage. They represent diverse schools that arose from the Buddha’s teachings.

Throughout the exhibition and the website, we explore how Buddhist artworks are endowed with sacred power. We ask, why were they created? How did Buddhists engage with them? And how do Buddhist understandings of such objects differ from those of art museums?

While pursuing answers, we highlight different contexts: grand shrines, intimate altars, royal palaces, artists’ workshops, and treacherous pilgrimage routes. All are sites for encountering the Buddha.

Our website features highlights from Encountering the Buddha and previews of its immersive installations, as well as links to the apps and podcasts created especially for the exhibition. Information on museum programs and resources for further learning are also included. We’ll be expanding resources and updating our program details on a regular basis; please stay tuned!

Buddhas Across Borders

Buddha: The Awakened One

The Buddha was born a prince in a kingdom on the border of Nepal and India in the fifth century BCE. Troubled by the inevitability of disease, aging, and death, he abandoned royal life to become a holy man. Six years of extreme self-discipline did not reveal a way to end the pain of existence. Finally, he sat under a tree, determined to acquire insight. His meditation led to the profound realization that attachments to impermanent things cause suffering. Through this enlightenment, he earned the designation Buddha, or “Awakened One.” The Buddha then taught others the path to overcome sorrow. In the centuries following his death, the Buddha’s teachings, or dharma, spread across Asia and became the foundation of Buddhism in all its forms. His life and image became central to Buddhist practice throughout the world.

Buddhas of the Past, Present, and Future

A buddha realizes the true cause of suffering and teaches the world how to overcome it. According to most Buddhist traditions, the Historical Buddha attained enlightenment through a process that had occurred countless times in the past. In every age, a remarkable individual rediscovers timeless truths and attains buddhahood. The buddha of the future awaits the chance to repeat the process.

Some traditions state that only one buddha may exist in an era. Others allow for many buddhas to be active in the world simultaneously. In the latter traditions, buddhahood is the goal for all humans, who seek assistance from the buddhas they worship.

As the number of buddhas grew, new forms of practice developed around specific buddhas. Because of their shared accomplishments, though, all buddhas are represented with the same physical characteristics.

Click on an image of a buddha below to learn more about it as a sacred object and an artwork.

Bodhisattvas: Travelers on the Path

The path to becoming a buddha is long and difficult. In most traditions, it takes countless lifetimes of exemplary virtue to achieve this goal. The journey to awakening begins with a sincere vow to become a buddha for the benefit of others. Those determined to follow this path to buddhahood are called bodhisattvas.

Motivated by profound compassion, bodhisattvas spend lifetimes perfecting their benevolent qualities, such as patience and wisdom. Because bodhisattvas have attained advanced spiritual states, they are able to assist others in worldly and religious matters. Thus, bodhisattvas are important objects of devotion for many Buddhists.

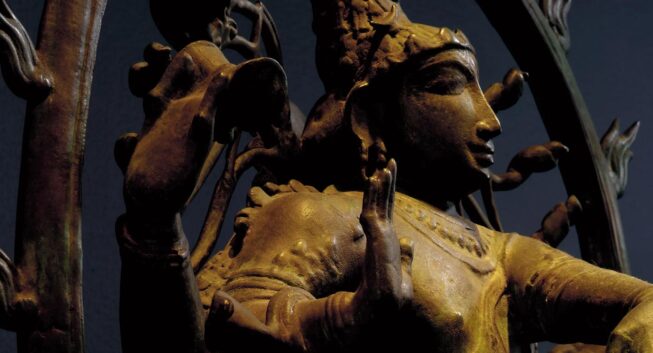

Artists typically depict bodhisattvas as radiant figures, richly adorned with jewelry. Bodhisattvas’ pristine beauty is an outward expression of their perfected inner virtues. It reflects the good karma they have garnered through innumerable virtuous deeds over many lifetimes.

Click on an image of a bodhisattva below to learn more about it as a sacred object and an artwork.

Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room from the Alice S. Kandell Collection

Whether small domestic altars or grand temple halls, the sacred spaces of Tibetan Buddhism are filled with images of enlightened beings and powerful deities. Sites of ritual performance and worship, such spaces present a spiritual hierarchy. Sonorous chants, flickering lamplight, and incense smoke inspire Buddhist practice.

Inside the shrine room within Encountering the Buddha, visitors encounter Tibetan Buddhist art in a manner that evokes the sacred precincts of the Himalayas. More than two hundred objects, assembled by the New York collector Alice S. Kandell over many years, reflect Tibetan Buddhist concepts and customs rather than museum conventions.

Explore the shrine room and discover the variety of Tibetan Buddhism’s sacred spaces, or download our free Sacred Spaces app to your phone or tablet. Tapping on objects in the app’s interactive panorama reveals information about their functions and meanings in the religious lives of Tibetan Buddhists. The app also includes images and films of different practices that take place within and around shrines, as well as an illustrated glossary.

The Texture of Practice: Sri Lanka’s Great Stupa

Stupas, hemispherical mounds that house sacred relics, are major sites of pilgrimage across the Buddhist world. Buddhists have visited the Ruwanwelisaya (pronounced Ru-on-way-li-saya) Stupa in Sri Lanka for more than two thousand years. Inspired by needs both spiritual and personal, believers come to receive blessings from the Historical Buddha’s bodily relics that the stupa is believed to enshrine.

Made of fired bricks, the stupa rises 338 feet from its foundation to its pinnacle—50 feet higher than the US Capitol. Ruwanwelisaya often is called “The Great Stupa” for both its size and the potency of its relics.

The video below offers a taste of the exhibition’s immersive film installation, which captures one day—from dawn to moonrise—of worship during Ruwanwelisaya’s monthly full-moon festival. The film reveals the texture and emotional power of a site that is at once broadly representative of Buddhist practice and distinctively local.

CREDITS Ambient sound, no narration. A film by Stanley J. Staniski; producer: Debra Diamond; content advisors and location coordinators: Lakshika Senarath Gamage and Sriyani Senarath Gamage; editor: Penny Trams; sound recordist and camera assistant: Janith Jayasekara; production assistant: Sachin Sanjeev. | View on YouTube

Hyecho, an Eighth-Century Buddhist Pilgrim

Remote Locations, Global Connections

![]() Religiously motivated travel has always been a part of Buddhist practice. Buddhist pilgrims visited nearby shrines and distant sacred centers, seeking blessings, good karma, and new teachings.

Religiously motivated travel has always been a part of Buddhist practice. Buddhist pilgrims visited nearby shrines and distant sacred centers, seeking blessings, good karma, and new teachings.

Alongside merchants and migrants, pilgrims crossed vast deserts and treacherous seas. Such long-distance travel brought ethnic, cultural, and religious diversity to otherwise remote locations, such as Kizil, an oasis town in western China. Over many centuries, hundreds of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean pilgrims braved countless dangers to visit places where the Historical Buddha had lived and taught

A young Korean monk named Hyecho traveled farthest. Around 724, he set out from China, beginning a journey over land and sea that would take him through the Buddhist holy land of India, as far west as Iran, and back to northern China. His journal and poems offer an intimate account of pilgrimage and a compelling view into Buddhist history.

A young Korean monk named Hyecho traveled farthest. Around 724, he set out from China, beginning a journey over land and sea that would take him through the Buddhist holy land of India, as far west as Iran, and back to northern China. His journal and poems offer an intimate account of pilgrimage and a compelling view into Buddhist history.

The interactive map in Encountering the Buddha allows you to explore many of the sites Hyecho described in his journal. At home, you can download it as a free app called Hyecho’s World. A second free app, Hyecho’s Journey, allows you to travel alongside the teenage Buddhist monk with games and objects in the National Museum of Asian Art collections. Both apps were created by undergraduates in the Multidisciplinary Design Program at the University of Michigan.

Further Learning

Dive deeper into Buddhist art and culture through a rich array of National Museum of Asian Art resources—from online exhibitions to recordings of past programs. For educators, our staff has created resources to help explain Buddhist art, culture, and practice within a classroom. For those who want an even deeper look, check out our scholarly programs and publications geared toward academic audiences.

Body of Devotion: The Cosmic Buddha in 3D

The Cosmic Buddha is a life-size limestone figure of Vairochana covered with detailed narrative scenes. Learn more about this spectacular sixth-century Chinese sculpture and our efforts to study it through 3D imaging.

A Journey to Xiangtangshan

Discover one of the crowning achievements of China’s Northern Qi dynasty (550–77): the Buddhist cave temples of Xiangtangshan. Through 3D imaging, experience these caves as they were before their tragic despoliation in the early twentieth century.

Masters of Mercy: Buddha’s Amazing Disciples

The Japanese artist Kano Kazunobu (1816–1863) produced one of the Edo period’s most impressive feats of Buddhist iconography: one hundred paintings depicting the miraculous interventions and superhuman activities of the Buddha’s five hundred disciples.

Return of the Buddha: Qingzhou Discoveries

A chance discovery in 1996 in Qingzhou, China, brought to light an incredible buried treasure: hundreds of well-preserved sixth-century Buddhist statues. Learn more about this remarkable discovery and the extraordinary wealth of knowledge

Silk Road Stories: How Asanga Came to See the Future Buddha

Drawing upon Tibetan traditions, this narration relates the tale of Asanga. Devoting his life to piety, Asanga spends twelve years meditating in the hopes of seeing the Future Buddha.

Time-Lapse Creation of a Sand Mandala

In March 2010, the Buddhist monk and mandala master Venerable Ngawang Chojor began creating a Tibetan sand mandala in the Sackler Gallery. The process, which requires great patience and focus, serves as an aid to Buddhist meditation.

Master of the Chinese Pipa: Wu Man

The musical composition Xiao Pu An Zhou heard on this concert recording is named for the twelfth-century Buddhist priest Pu An, who is said to have gained enlightenment by chanting sacred mantras. Wu Man adapted this composition to include an effect that imitates the clacking of temple woodblocks.

Modern Awakenings: New Music Inspired by Buddhism

In this compelling concert, the Momenta Quartet performed music for violin, viola, and cello by four composers who draw inspiration from Buddhist philosophy and practice.

Making Musical Waves: The Legacy of Yatsuhashi

The Japanese bamboo flute called shakuhachi is closely associated with the spread of Zen Buddhism in Japan. Wandering monk-musicians played the often-abstract music for this instrument while begging for alms. This concert features shakuhachi master Yodo Kurahashi, along with artists performing the koto, shamisen, and vocal parts.

Painting with Music: Bell Yung, Qin

The repertoire of the ancient zither called qin (pronounced “chin”) embodies China’s major religious-philosophical systems of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. Some of the most distinguished qin musicians were Buddhist monks, who played the instrument in the seclusion of their temples and passed their music to younger disciples.

Music for Qin on Piano: Jenny Lin

The twentieth-century composition The Willows are New by Chou Wen-Chung elaborates on Yung Kuan, a traditional Chinese melody. Yung Kuan is part of the ancient literature for the qin, the Chinese seven-stringed zither, which is closely associated with Chinese Buddhism and often played by Buddhist monks.

Music From Japan: Echoes of the Silk Road

This ensemble plays instruments reconstructed from those found in the Shoso-in, an eighth-century repository at a Buddhist temple complex in Nara, Japan. The Shoso-in also houses music notation from the same period, which inspired the works in this program.

Sukeyasu Shiba’s Gagaku Universe

Twenty-five musical manuscripts were discovered in one of the ancient Buddhist caves at Dunhuang, western China. One manuscript, reconstructed by Japanese composer Sukeyasu Shiba in 1983, is heard on this concert recording. The instruments used are modern versions of those found in the Shoso-in.

Portrait of Hwang Byungki: New and Traditional Music for Korean Instruments

First performed in 1974, Ch’imhyangmu is a musical exploration of Buddhist art from the period of the Silla kingdom. It combines indigenous and Western elements to sublimate sensual beauty on Buddhist principles. For this piece, the strings of the kayagum are tuned to a scale used in Buddhist chant.

How can you bring Encountering the Buddha: Art and Practice across Asia into your classroom? Educators of many disciplines and grade levels can use this exhibition as a teaching and learning opportunity. Use these resources to deepen your understanding of the ways in which art and place embody and express the teachings of Buddhism across Asia.

Background Reading and Context

Buddhism and Buddhist Art | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Explore Buddhism’s key tenets and important historical figures and events, and discover how the representation of the Buddha has evolved over the centuries on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

Life of the Buddha | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Read this introductory essay from the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History to learn more about the life of the Buddha, and dive deeper into the subject with related essays and chronology.

An Introduction to Buddhism | Asian Art Museum, San Francisco

Visit this website for downloadable student activities, teacher resources, videos, and more focused on teaching about Buddhism in K–12 classrooms.

Pinterest | National Museum of Asian Art

Use our educators collection on Pinterest to build your online bulletin boards. Pin selected images to share resources and information, curate content, organize ideas for classroom projects, and collaborate with others.

Cosmic Buddha in 3D | National Museum of Asian Art

Explore a 3D model of a life-size, sixth-century Chinese limestone figure of the Cosmic Buddha. What makes this object exceptional are the detailed narrative scenes that cover its surface, representing moments in the life of the Historical Buddha as well as the Realms of Existence, a symbolic map of the Buddhist world.

More

Plan Your School Visit

Submit this request form for a docent-led tour four weeks in advance, and bring your students to experience Encountering the Buddha and the National Museum of Asian Art’s related collections in person.

Events and Workshops

Register for professional development workshops and learn about public programs related to the exhibition.

The Performative Agency of Buddhist Art and Architecture in Asia

Ars Orientalis, volume 46

Guest-edited by Michelle C. Wang and Wei-cheng Lin

Smithsonian Institution, 2016

Scientific Research on the Sculptural Arts of Asia: Proceedings of the Third Forbes Symposium at the Freer Gallery of Art

Edited by Janet G. Douglas, Paul Jett, and John Winter

Archetype Publications with the Freer Gallery of Art, 2007

The Buddha as the Yogin: The Making of a Nationalist Art History

Sugata Ray, University of California, Berkeley

From “Yoga and Visual Culture: An Interdisciplinary Symposium” (November 21–23, 2014)

Holiness, Heat, and Hunger: Sculpting States of Mind

Robert DeCaroli, George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia

From “Yoga and Visual Culture: An Interdisciplinary Symposium” (November 21–23, 2014)

Want to learn more about Buddhist art, architecture, and practice? Check out other digitized NMAA publications.

For Kids

What do you think of when you hear the word “Buddhism”? Meditation or a smiling man with a round belly might spring to mind—but Buddhism involves much more than that. In fact, that “Laughing Buddha” is not traditionally understood to depict the Buddha at all.

Buddhism is a complex religion that has been around for twenty-five hundred years. Encountering the Buddha, an exhibition at the National Museum of Asian Art, explores Asia’s rich Buddhist heritage through more than two hundred artworks. It also shows how different schools based on the Buddha’s teachings developed over time.

In this web feature, you will find a selection of our Buddhist objects. Learn more about them through interesting facts, discussion questions, and art-making activities. Experiment with creating a gilded object, a guardian figure, and your own storyboard inspired by the Buddha’s life events, among other fun projects.

What is it made of? Bronze with a thin layer of gold

Where was it made? China

When was it made? Sui dynasty, 597 CE

Discover

Take a look at this altarpiece—a religious sculpture that believers focus on during prayer or meditation. This sculpture features a buddha standing between two bodhisattvas (beings who have reached enlightenment and want to help others). Although this object may look like it is made of solid gold, it was actually made of bronze that was gilded, which means a thin layer of gold was applied to the surface. As you can see, the gilding is peeling off the statue because it was buried underground for a thousand years. Sometimes, if a religious sculpture was no longer being used, it was buried, which showed more respect than throwing it in the trash.

Understand

Gold was expensive in sixth-century China, so only the richest people, including nobles, could afford it. On the base of the sculpture, you can see writing that includes the names of sixteen women who pitched in to have this altarpiece made. Some of these donors seem to have had royal connections!

Imagine

The Buddha teaches that physical change is inevitable—and the same applies to this sculpture! Think of what this altarpiece might have looked like before and after gilding, and how it has changed to look the way it does now.

Create

Do you own something that you want to look like solid precious metal—even if you’re not an emperor or empress? Gild your own object! Or, you could silver-plate it by adding a thin layer of silver on top of a less expensive material. Since most of us do not have silver leaf handy, try wrapping a cherished object in aluminum foil to make it sparkle and shine. Where will you display it?

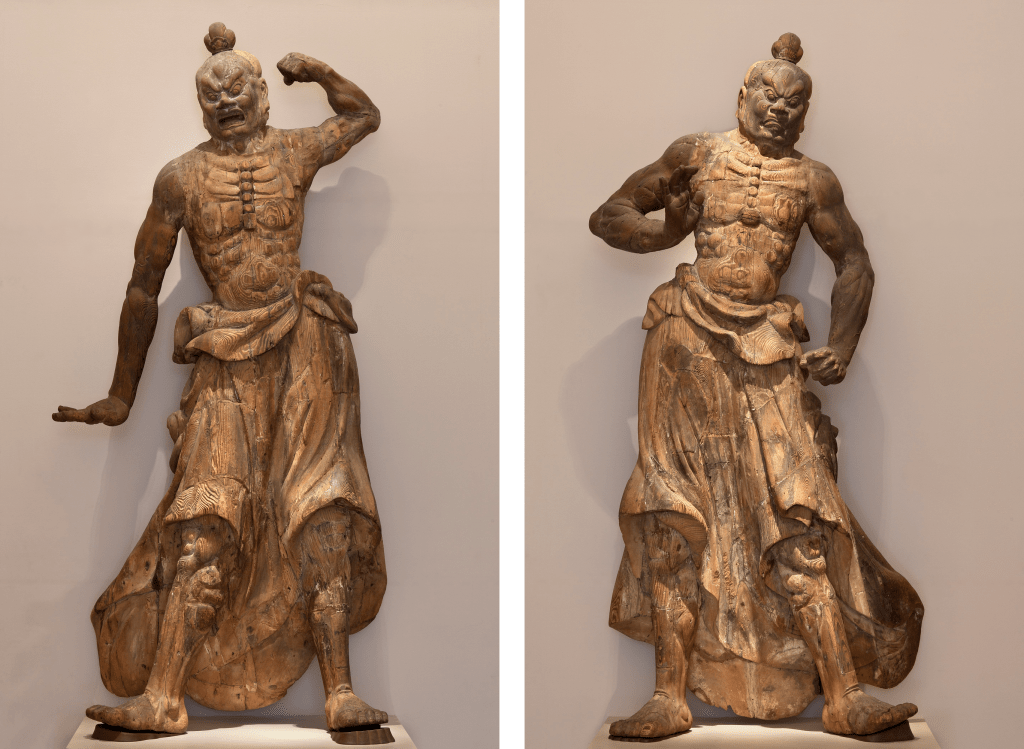

What is it made of? Wood

Where was it made? Japan

When was it made? 1185–1333

Discover

Don’t get too close! These two large, wooden guardian figures once kept watch over the Buddha and his followers outside a temple in Japan. Their size, active poses, and bulging muscles illustrate their power to drive away evil. At more than seven feet tall, these larger-than-life sculptures stand above most people! How would you feel standing next to one of them? Try it out by visiting the Freer Gallery of Art, where the figures stand guard in the corridor.

Understand

Did you notice how one figure has his mouth open and the other’s is closed? The open-mouthed sculpture is saying “ah,” the Japanese sound for the beginning of the alphabet. The closed-mouthed guardian is saying “om,” which is the alphabet’s last sound. Together, the guardian figures are thought to demonstrate that the realm of the Buddha is infinite.

Imagine

The guardian figures were originally painted, but their color has since worn off. Imagine what they would have looked like hundreds of years ago. Share aloud what colors you think the sculptures originally had. How would color make the figures seem different? What do you think would happen if these two figures came to life?

Create

Today, inspired by figures like these guardians, Japanese artists continue to create stylized graphic novels known as manga. Draw your own guardian that would make a great protector. You might even try modeling your figure out of clay. Give your guardian a name, and write down two adjectives that best describe it. What would you want your guardian to protect?

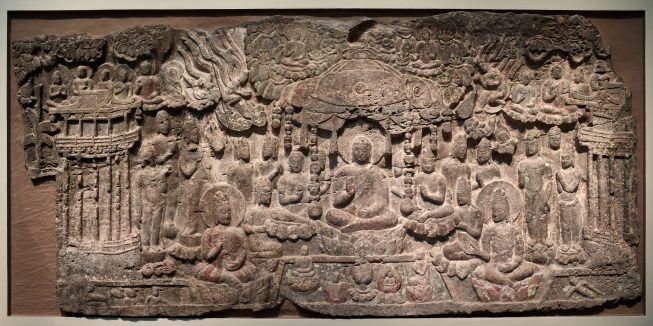

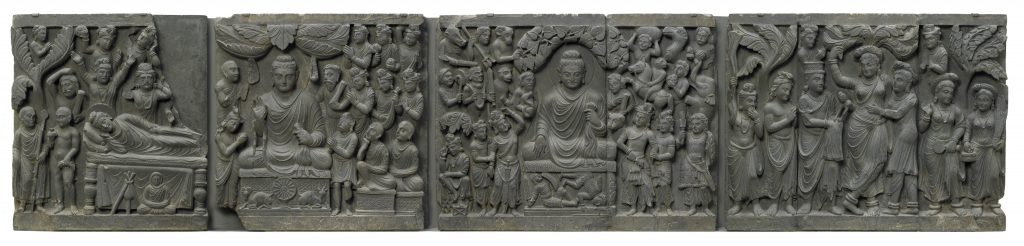

What are they made of? Stone

Where were they made? Pakistan or Afghanistan

When were they made? Late 2nd–early 3rd century

Discover

These stone panels were made for a stupa, a dome-shaped shrine to the Buddha, which followers walk around to show respect for his teachings. The panels depict the four most important events of the Buddha’s life (from right to left): the moment of his birth, his achievement of enlightenment, his first sermon, and his death. Can you find the Buddha in each of the panels?

Understand

Today, a temple surrounds the pipal tree at Bodh Gaya, India, where the Buddha achieved enlightenment twenty-five hundred years ago. Buddhists from all over the world take long journeys to reach Bodh Gaya in hopes of coming closer to enlightenment—the state of being fully awake and understanding everything. Explore Bodh Gaya yourself with 360° views!

Imagine

In the second panel, the Buddha meditates beneath the pipal tree at Bodh Gaya. He reaches down to touch the earth and defeats the demons who have been trying to make him lose his focus. Imagine the challenges he might have had meditating in the middle of a city like Washington, DC!

Create

Let’s get creative! Design your own life storyboard in four panels. What moments in your life do you want to share with others? Consider whom else you will include in these panels. Once you’ve decided, fold two pieces of paper in half. Draw a line down each fold, and then draw an important scene from your life in each of the four sections. Glue popsicle sticks to the edges of the pieces of paper and connect two of them to make a four-part panel.

What is it made of? High tin bronze

Where was it made? Indonesia, Central Java

When was it made? 8th–9th century

Discover

The medicine buddha (Bhaishajyaguru, pronounced Bye-sha-jya-gu-ru) is at the center of an important Buddhist tradition. Followers of Buddhism, a major world religion, worship the medicine buddha to relieve sickness and suffering—whether it’s from serious illnesses or itchy mosquito bites!

We can tell that this bronze represents a buddha from the mark on his forehead, the bump on top of his head, his long earlobes, and his monk’s robe. We know this is the medicine buddha because his right hand holds the amla fruit, which is very high in vitamin C.

Understand

The medicine buddha is understood to be a brilliant blue color. His complexion is compared to the blue of lapis lazuli, a type of precious stone. Many Buddhists value lapis because they believe it has healing powers. The stone can be ground into a fine powder and used as paint in Buddhist artworks.

Imagine

Buddhism began in India, but this sculpture was made far away on the island of Java, Indonesia. Today, traveling from northeastern India, where the Buddha taught, to Java takes a ten-hour car ride followed by a seven-hour flight! Without planes, trains, and cars, the journey took much longer.

Create

Sacred verses called href=”https://youtu.be/NVdIWJQJ6GU?t=5m”>mantras are part of Buddhist practice. Some verses are believed to prevent illnesses or protect people from their fears. Write a poem or a song that you can sing when you experience something painful, like a skinned knee. Think of the song as a force field to take your mind away from the pain.

What is it made of? Copper alloy

What is it made of? Copper alloy

Where was it made? Cambodia

When was it made? circa 1200

Discover

For Buddhists, knowledge is so important that it is personified as a goddess! This figure’s name is Prajnaparamita. In Sanskrit, an Indian language with ancient roots, the word prajna means knowledge, and paramita means supreme. Prajnaparamita helps devotees understand the true meaning of life. This deep understanding is known as enlightenment.

Understand

More than eight hundred years ago in Cambodia, a king declared Buddhism as the state religion. He built a temple that equated his mother with the goddess of knowledge. Buddhists revere this goddess as the mother of all buddhas. By building the temple, could the king have been comparing himself to the Buddha?

This image of the goddess of knowledge has twenty-two arms and eleven heads! She holds a manuscript and a lotus bud in her first two hands, and her twenty other arms fan out like fierce wings.

Imagine

Buddhists aim to reach enlightenment, or complete understanding of everything. What is one thing you want to know more about? Imagine yourself as Prajnaparamita. What could your supreme wisdom help you accomplish?

Create

The Cambodian artist who sculpted this figure had to figure out how to represent twenty-two arms on a single body. Step into the role of the artist and build a self-portrait of yourself out of clay, adding extra heads and arms. Once you’re done, chat with friends and family about the challenges you had. How did you use your supreme wisdom to problem-solve?

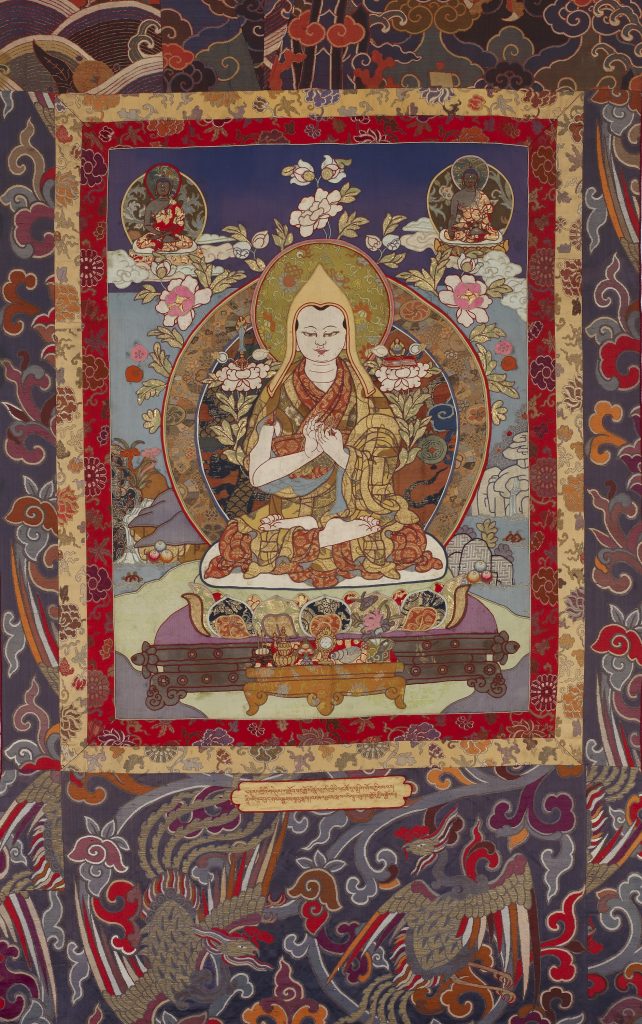

Central Tibet, Lhasa, 1834

Appliqué using Chinese (Qing) and Russian brocades, leather, pearls, and couching threads (horsehair wrapped in silk with gold foil)

154.9 x 106.7 cm (61 x 42 in)

The Alice S. Kandell Collection

ELS2010.4.91

What is it made of? Precious silk, couching threads (horsehair wrapped in silk and gold foil), leather, and pearls

Where was it made? Historical Tibet

When was it made? 1834

Discover

Although many Tibetan hanging artworks (thangkas) are painted, this one was made using a technique called appliqué. To make an appliqué thangka, an artist stitches together small pieces of fabric to create pictures or patterns.

In the center of this thangka, we see the great Tibetan Buddhist teacher Tsongkhapa (pronounced Tsong-ka-pa) seated in deep meditation. Two lotus flowers rise over his shoulders: a flaming sword stands on the left flower, and a book with a red cover rests atop the other bloom. These two objects symbolize Tsongkhapa’s extraordinary wisdom.

Understand

Thangkas are commonly used as tools to help Buddhists understand spiritual teachings. They may also be used as images to focus on while meditating. Thangkas of all kinds hang in shrines and behind altars, but some are only displayed for special events. The rest of the time, they are rolled up and stored for safekeeping.

Imagine

Sewing together fabric pieces to create flowers and other shapes in this thangka took a long time and a lot of concentration. Imagine yourself as a Tibetan artist. Do you think you would have the patience to stitch such complicated patterns? Might you be able to do the same thing through painting or collage?

Create

Some people meditate while sitting in the same pose that Tsongkhapa is in. It’s called the lotus pose because it makes your feet look like the petals of lotus flower. With practice, you can sit like this for hours. Try for yourself, and see how long you can hold it!

Related Publication

Buddhism and the Senses: A Guide to the Good and Bad

Author List: Robert DeCaroli and Donald S. Lopez Jr. (eds.)

Publisher: National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution; in association with Wisdom Publications

Publication Date: 2024

Across Buddhist traditions, the five senses—sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch—are perceived both positively and negatively. Share our eminent scholars’ fascination and deep insight into what makes a sensuous experience good or bad. Ten eminent scholars present their insights into Buddhism’s fascinating relation with the five senses, which careens between delight and disgust, rarely finding a middle way.

Support

The National Museum of Asian Art gratefully acknowledges the exhibition’s lead sponsor

Established in 2005, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation is a private philanthropic organisation based in Hong Kong. The Foundation’s mission is to foster appreciation of Chinese arts and culture to advance global learning and to cultivate deeper understanding of Buddhism in the context of contemporary life. The Foundation supports the development of a global Buddhist learning network as well as collaborative and innovative programmes that present Buddhist art in a fresh light.

This project received Federal support from the Asian Pacific American Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center. Additional funding provided by the Ellen Bayard Weedon Foundation

The National Museum of Asian Art is grateful for the contributions of University of Michigan Humanities Collaboratory and the Multidisciplinary Design Program.

Related Exhibitions

-

The Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room

Ongoing

Detail of gilt copper sculpture of Tara, Tibetan Buddhist bodhisattva, with intricate turquoise and coral inlays.

- Jump To...