Jerusalem, The Shrine of the Book, 95.57/26B

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (owner)

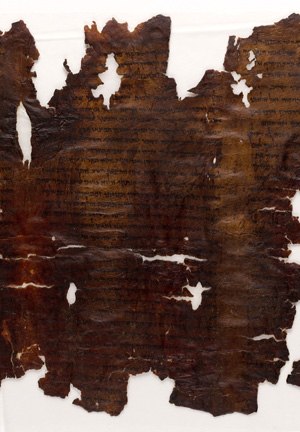

MS. B (1QIsab [1Q8])

Ink on leather; 1 leaf (part of a scroll); 220 x 430mm

Bible (fragment); Hebrew

Judaean Desert, Israel; before 73 C.E.

The Second Isaiah Scroll is part of an original repository of seven found by Bedouin of the Ta’amra tribe in a cave near Khirbet Qumran, on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea, between late 1946 and mid-1947. This scroll was one of three subsequently purchased by a Bethlehem antiquities dealer, Faidi Salahi, who in turn sold them at the end of 1947 to Prof. Eliezer Lipa Sukenik of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The first publication of the scroll in English, by Sukenik in 1955, included a short introduction, a transcription of the text, and photographs.

Additional fragments of the scroll were found scattered in the same cave (now called Cave 1) in the excavations conducted in 1949 by the Dominican scholar, Fr. Roland de Vaux, of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française, under the auspices of the Jordanian Department of Antiquities. The fragments were published in 1955 by Barthélemy and Milik.

This scroll reached us in very poor condition. Regrettably, all that survived was the upper portion of the last third of the biblical book of Isaiah, and a few fragments of the early and middle sections. Written in a Herodian (that is, the period of Jewish history from 30 B.C.E. to 70 C.E.) Hebrew script and dated to the first century C.E., the section of the scroll illustrated here contains four columns (8—11) with an average of thirty-four lines each; an estimated fourteen lines at the bottom of the scroll have been lost. It contains Isaiah 52:7—8 to 61:2; it is the best preserved of the four sheets found. The text of this Isaiah scroll is close to the fixed Masoretic text of medieval codices, but not as close as appeared at first. Some differences are minor—column 9, line 18 reads hanilvah al, while the traditional text has hanilvah el, “has joined himself to” (56:3)—while others are more significant. The word or, “light,” which appears in column 8, line 22 of this scroll, for example, is missing from the Masoretic text (53:3). Conversely, the Masoretic text includes the phrase tze’u mitocha, “go out of the midst of her” (52:11) while this scroll does not. On the other hand, there are passages in the scroll that are different to the Masoretic text, but identical to the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible in circulation at the time the scroll was written: roshcha, “your head” (column 10, line 12) rather than rosho, “his head” (58:5), for example. In addition, the scroll uses the mixed “plene” or full spelling (ktiv malei) and “defective” Hebrew spelling (ktiv haser), as in the Masoretic text, rather than the plene form usually found in the other scrolls, biblical and sectarian alike, discovered in the Qumran caves between 1947 and 1956.

Apart from this scroll, parts of twenty separate copies of the book of Isaiah were found in the Qumran caves—one complete (1QIsaa) and all the others fragmentary (4Qa-r, 5QIsa)—and another manuscript in Wadi Muraba’at (MurIsa). Isaiah appears to have been the most popular biblical book of the Qumran community, after Psalms (thirty-six copies) and Deuteronomy (thirty copies). Six pesharim (sectarian commentaries) are devoted to it, and it is the most widely quoted in other scrolls. Most scholars recognize the Qumran community as a sect of Jewish separatists, perhaps a radical group of Essenes mentioned in the ancient writings of Flavius Josephus, Philo of Alexandria, and Pliny the Elder. The evident special status they accorded Isaiah—the eighth-century B.C.E. Judaean prophet who predicted the end-times—is consistent with their messianic and eschatological world-view.

Author

Adolfo Roitman, Ph. D.

Curator of the Dead Sea Scrolls and Head of the Shrine of the Book, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Bibliography

Barthélemy and Milik, 1955; Sukenik, 1955; Ulrich, 2000; VanderKam and Flint, 2004.