In mid-September 2010, the decision was made to award the Freer Medal to James Cahill, a distinguished historian of Chinese art history. Cahill would be the twelfth recipient of the medal in its 54-year history, and the first in almost a decade; the last award had been made in 2001, to Oleg Grabar.

Jim graciously agreed to travel to Washington for the mid-November award ceremony, and museum staff began planning the event. In early October, we turned our attention to the medal itself, which of course would have to be engraved with Jim’s name and the date of the award.

But there were no blank medals to be found. It had been years since the last ceremony, and although records indicated that the previous medal was engraved, no one could remember where the blank version had been stored. Longtime staffers were canvassed, previous directors were contacted, storage was checked, and safes were opened—all to no avail.

This seemed odd. So far, 11 medals had been awarded. Why would the museum have originally commissioned such a random number of medals? Surely 15 or 20 would have been a more logical number. We believed there must be more medals tucked carefully away, but no one could find them.

This presented an intriguing research project: tracking down other examples of the Freer Medal; or, perhaps, records of the medals’ original production, which could lead to the foundry where they were made.

A short online search revealed that many archives on Paul Manship, the artist who made the original medal, were right here in the Smithsonian, in the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM). As more than 50 years had elapsed since the original medals were made, colleagues at SAAM advised against searching Manship’s papers for information about the moulds or dies for the medal, suggesting that it would be faster to try creating a replica. Fortunately, SAAM’s Luce Foundation Center for American Art had in its collection two artist’s proofs of the medal, which we could use as the basis for a re-creation.

Upon further consultation with Smithsonian colleagues, we learned that there are two ways to reproduce a medal. One method involves making an impression of the original, which is used to create a mould that can then be used to produce a die from which new medals can be cast or struck. The other involves using 3D imaging technology to produce a digital image, which would be the basis for creating new medals.

Scientists at the Museum Conservation Institute have been experimenting with 3D imaging technology and were willing to take on the project. At the same time, technicians at the Smithsonian Office of Exhibits Central volunteered to work with the Luce Foundation Center objects to create a mould. In the end, we opted against 3D imaging, since the reflective surface of the medals could have caused distortions in the image. SAAM agreed to loan the medal to the Office of Exhibits Central so that an impression could be made and a mould created.

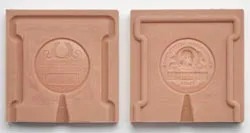

There were more twists to come. When we applied to borrow the artist’s proofs from the Luce Foundation Center, we requested only one of the two in the collection. To our surprise, each contained half of the image: one showed the front side of the medal design and the other showed the reverse. The curator thus wisely suggested that we borrow both instead.

When Chris Hollshwander in the Office of Exhibits Central began working on the mould, he discovered that the two medals were slightly different sizes and that the edge of each one had been finished with a slightly different design. The project was considerably more complex than he had envisioned, but he did a spectacular job.

Once the mould had been made (it looks like a big pink eraser from the outside), the medals were safely returned to the Luce Center, and the mould sent to a foundry in Minnesota. There a new set of dies were made, and a new set of medals was struck. This time we ordered 20—enough for many decades of Freer Medal awards.

The long process of research and re-creation was not completed in time for the award ceremony. On November 18, James Cahill received a cardboard replica of the medal, elegantly presented in a wood box lined with Chinese silk. A beautiful new bronze medal, engraved with his name and the date of his award, was sent to him the following May.

In June, a white, slightly battered cardboard box was delivered to a museum office by a security guard. It had been found in a small safe, long overlooked in a corner of an office. Inside was a collection of outdated documents and various odds and ends.

The only thing of value in the safe was in the white box: one Freer Medal, which makes the twelfth of the museums’ original set, an even dozen. Our search for the missing medals was over.