Charles Lang Freer’s Letterpress Volumes and the Art World at the Turn of the Century

The digitization of Charles Lang Freer’s letterpress books transforms fading, fragile pages into permanent records and renders accessible to all a fascinating trove of turn-of-the-century cultural and business documentation. Although these volumes were microfilmed in 1992, the result was often illegible and cumbersome to browse. Those who, like me, wanted to learn about Freer in his own words had to spend weeks (or months) making by-appointment-only visits to the National Museum of Asian Art Archives in Washington, DC, to page through the original letterpress books one delicate folio at a time, magnifying glass at the ready. We had to copy down relevant information by hand or transcribe it into our laptops, because the leaves of these disintegrating volumes could not be photocopied.

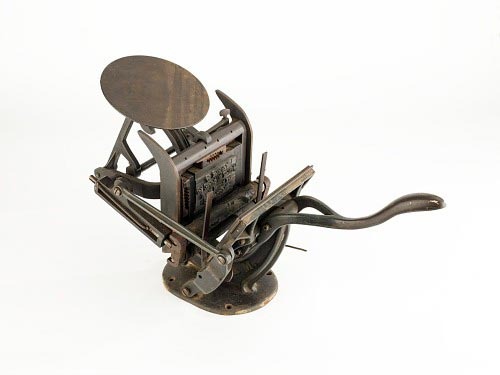

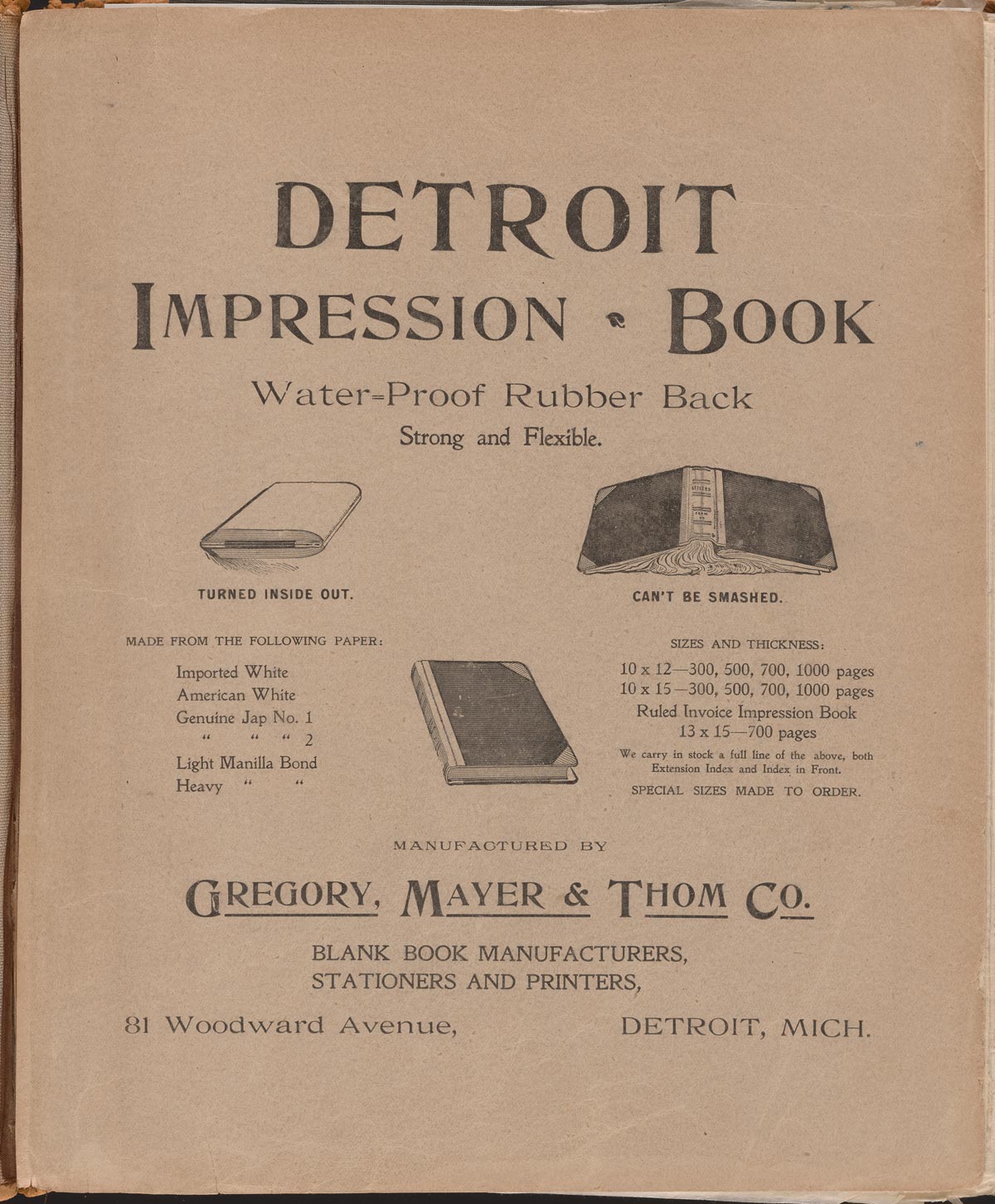

Such extraordinary efforts were worthwhile, because Freer’s letterpress books contain such valuable and sometimes surprising information. These bound compilations of Freer’s typed and occasionally handwritten letters look like carbon copies to twenty-first-century eyes, but their impressions were actually taken with a letterpress: a device that works a bit like a miniature printing press, using water-soluble ink and translucent paper to transfer copies of correspondence directly into a bound book for record-keeping. The letterpress was a century-old technology by the time Freer and his assistants deployed it, but the blank books he ordered from office supply companies in Chicago and Detroit in the 1890s and 1900s bear the trademarks of patented, state-of-the-art improvements in materials and indexing systems. They reflect the increasingly standardized and systematized office world to which railroad car builder and accountant Freer belonged.

By giving scholars access to the historical equivalent of an email account’s sent folder, the letterpress copies allow us to read Freer’s correspondence in relation to particular events (such as the World’s Columbian Exposition, the creation of the American Car and Foundry Company, and Freer’s gift of his collection to the nation) or purchases (including objects seen and acquired through countless visits to Yamanaka & Co. in New York as well as his acquisition of the Peacock Room in 1904). They enable us to compare how he described these occurrences to various friends and colleagues in letters written around the same time. Researchers should note that some volumes overlap with others chronologically and so must be consulted in parallel. When compared with the archive’s holdings of Freer’s correspondence (largely letters sent to Freer), the letterpress copies sometimes enable us to reconstruct entire conversations.

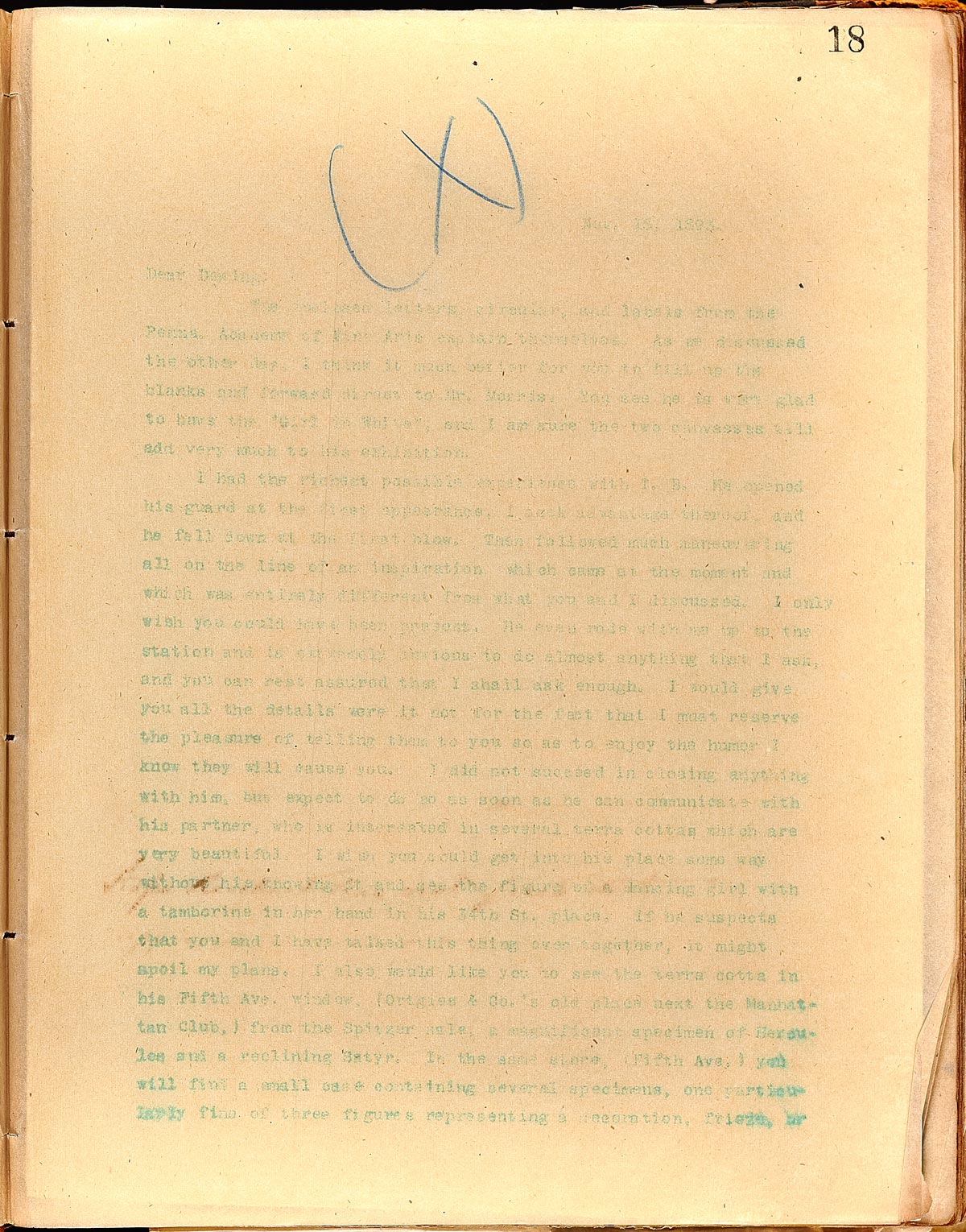

Among these volumes’ most important revelations are the manifold ways in which Freer’s business and art collecting activities were thoroughly intertwined. Some early letterpress copies are marked PERSONAL, but this designation disappears after a while, further underscoring the fact that letters to his business associates (such as Frank J. Hecker and William K. Bixby) also discuss his interactions with artists and reveal his efforts to place their paintings in various museums and private collections. Likewise, the volumes document his discussion of business matters with—and sometimes his sale or gift of corporate stock to—the artists in his orbit (namely Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Dwight W. Tryon, Abbott H. Thayer, and Frederick S. Church). While one can use the handwritten entries in the indexes that appear at either the front or the back of each volume to jump directly to the numbered folios containing letters written to those individuals, researchers should not limit themselves to these lists of names, because wading into adjacent letters in a volume, printed around the same date, will often yield further details surrounding a particular incident.

And as much as these documents tell us about individuals in very specific situations, they also reveal a great deal about the wider late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American art world that might otherwise have been harder to see. As I have noted elsewhere, we have little access to the gossip, social maneuvering, and interpersonal negotiations that took place between individuals living and working in the artistic hub of New York. But because Freer lived in Detroit, traveled frequently to New York, and exercised varying degrees of influence over exhibitions and institutions in such cities as Washington, DC, Boston, Chicago, and St. Louis, he was forced to conduct many conversations in writing rather than in person. He and his correspondents put into their letters details they might have only whispered to others in passing at the club or in the studio. Consider volume 3, folios 18–19, in which Freer and Dewing scheme to get their hands on art collector and dealer Thomas B. Clarke’s tanagra figures without letting Clarke know Freer is interested. They commiserate about their negative experiences working with Clarke, conspire to cut off communication with him, and actively prevent him from reacquiring a George Inness painting he desired.

Anyone interested in the daily machinations and minutiae of turn-of-the-century American art and business spheres will find much rich material here, from behind-the-scenes corporate collaborations to the specific packing methods for shipping paintings from place to place (and the methods for and expenses of repairing them when they were inevitably damaged). The digitization and global availability of these fragile, singular documents will have an immediate and long-term impact on how we understand the complexities of these worlds.