The Women Who Helped Establish the Freer Gallery

Correspondence in the Charles Lang Freer Papers illuminates the important roles that women had in establishing the Freer Gallery of Art. Industrialist-turned-art-collector Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919) was a pioneer when it came to facilitating the success of many women artists, administrators, and art collectors in the early twentieth century. Among those women were Katharine Nash Rhoades (1885–1965), Grace Dunham Guest (1872–1964), Agnes Ernst Meyer (1887–1970), and Louisine Havemeyer (1855–1929). Freer designated these women trustees, curators, and special advisors to the Freer Gallery before he died in 1919. During my initial visit to the archive six years ago, I was struck by Freer’s deep respect and admiration for these women. Their correspondence humanizes Freer, who was an otherwise elusive and private businessman. In some cases, correspondence with one woman mentions the name of—or is addressed to—one of the other women.1 This shows how Rhoades, Guest, Meyer, and Havemeyer were linked through their work with Freer and forged a network while establishing the Freer Gallery.

Katharine Nash Rhoades began her career as a photographer and art dealer at Alfred Stieglitz’s Gallery 291. Rhoades was from one of New York’s wealthiest families and never married or had children. As a wealthy single woman, she had freedom to pursue a career. After meeting Freer through their mutual friend, art collector Agnes Meyer, in 1913, Rhoades left New York behind to curate Freer’s collection.2 From then on, Rhoades helped the collector finalize plans for the Freer Gallery and prepared his vast collection of Asian and American art for its move from Freer’s Detroit home to his namesake gallery in Washington, DC.

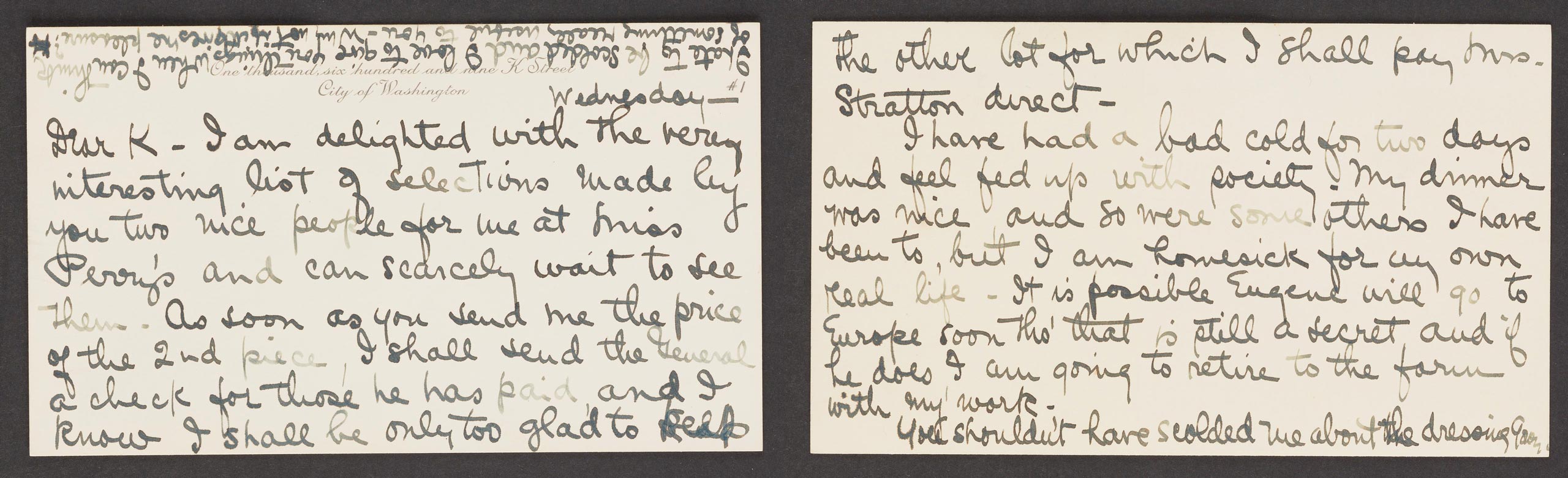

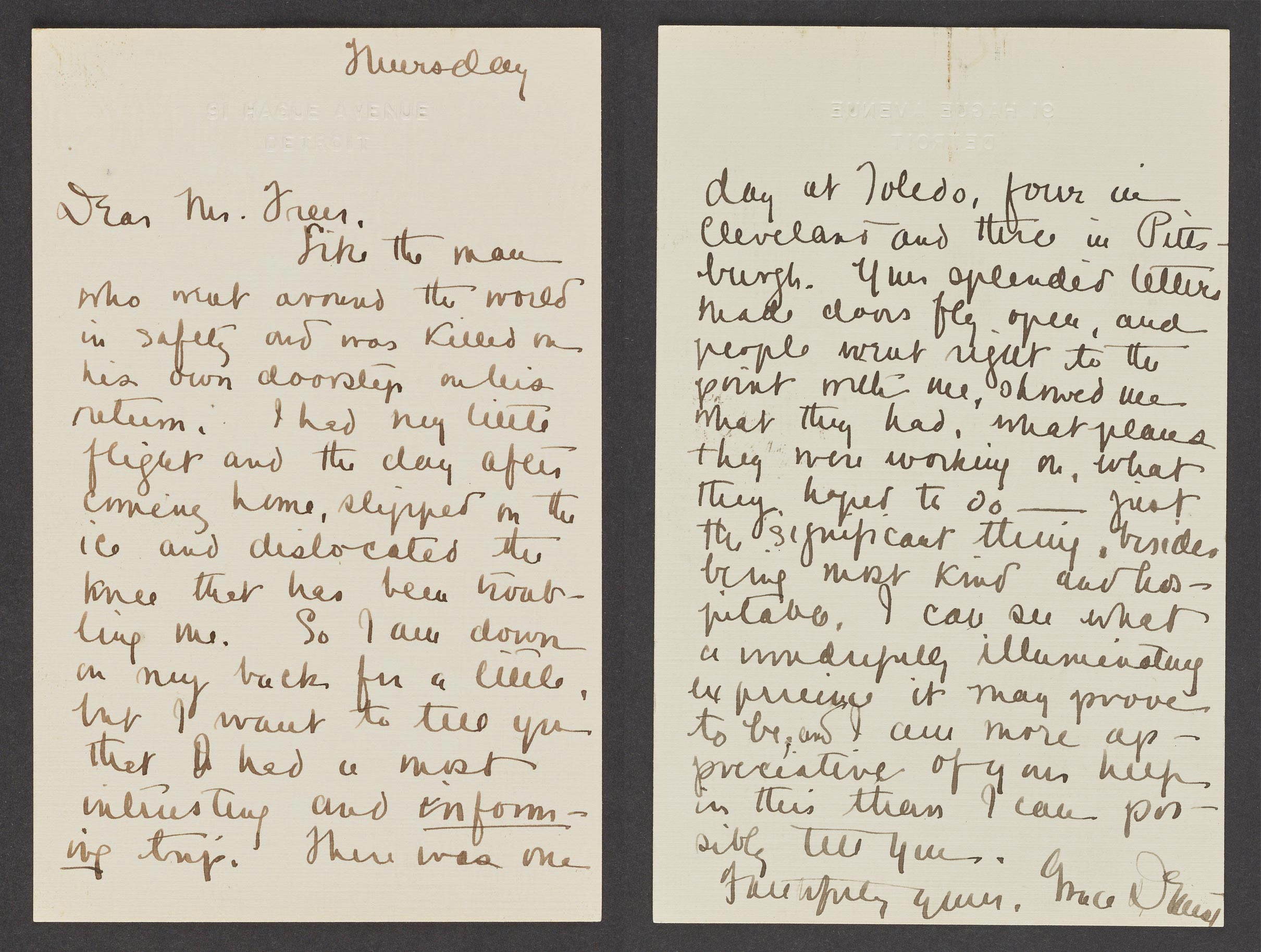

Freer and Rhoades’s correspondence highlights how Rhoades’s job extended beyond that of a typical curator. She typed Freer’s letters and memoranda and settled bills as Freer added art to his collection. Like Rhoades, Freer had no spouse or children, so she fulfilled those roles as Freer’s health deteriorated during the last decade of his life. Freer often ended his letters to their mutual friends with a greeting from “Miss Rhoades” or “K,” which is evidence of their constant togetherness. Though the stress of caring for Freer led Rhoades to seek therapy and rest at a sanitorium at least twice, she remained steadfast in her commitment to her friend and employer and to his collection. In turn, Freer entrusted the future of his collection to Rhoades by making her a trustee of his museum. In August 1919, just weeks before Freer died, he wrote to Smithsonian secretary Charles Walcott that Rhoades had “insight and thorough understanding of the collection,” and that Walcott and the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents should consult with her on “matters of importance.”3 After Freer died, Rhoades moved to Washington to work as an “associate” at the gallery. She oversaw the move of Freer’s collection from Detroit, helped convince John Ellerton Lodge to accept the job of Freer Gallery director, worked with architect Charles Platt on the museum’s design, and collaborated with Lodge and Agnes Meyer to expand the collection. Rhoades continued to run day-to-day business at the Freer Gallery until her retirement in 1938. She was a trustee of the museum until her death in 1965.

Like Rhoades and Freer, Agnes Meyer and her husband, Eugene Meyer (1875–1959), a banker who eventually became publisher of the Washington Post, were avid art collectors. When Eugene became president of the War Finance Committee in 1917, the Meyers moved from New York to Washington. Agnes Meyer was the Freer Gallery’s unofficial spokesperson and helped publicize the museum among Washington elites before it opened in 1923. Freer encouraged her to study Chinese art and allowed her to photograph Chinese scrolls from his collection for her book, Chinese Painting: As Reflected in the Thought and Art of Li Lung-Mein, which she dedicated posthumously to Freer in 1923.4 Freer also helped Meyer expand her art collection by giving her access to shipments of art from his dealers and advising her about which works to purchase. Meyer was instrumental in adding important works to Freer’s collection. In 1916, she and her husband purchased a large stone bodhisattva from the Buddhist Cave Temples in Xiangtangshan, China, as a gift to Freer for his museum. When Meyer died in 1970, she willed the majority of her vast Asian art collection to the Freer Gallery. Because Meyer and Freer had built their collections side-by-side, the breadth of her collection mirrored his.

Louisine Havemeyer was a trustee at the Freer Gallery who worked closely with Freer on his collection. The two met through Freer’s art advisor, Ernest Fennollosa, in the early 1900s. After Louisine’s husband, sugar industrialist Harry O. Havemeyer (1847–1907), died, Louisine went to work as a spokesperson for the women’s suffrage movement. Havemeyer gave speeches to large crowds during whistle-stop tours and hosted two exhibition fundraisers to raise money for the movement. When she was not campaigning for suffrage, she and Freer visited one another regularly to discuss their art collections. Freer and Havemeyer’s friendship is suggested in these letters. Freer offered his home in the Berkshires to Havemeyer so she could rest between campaign activities in 1917.8 During World War I (1914–18), Freer facilitated donations to Parke-Davis, a Detroit pharmaceutical company, on Havemeyer’s behalf. The donations were for medical supplies that were sent to troops in Europe. One letter from 1914 discusses the first of three donations Freer made to Parke-Davis and the Red Cross on Havemeyer’s behalf.9 The money may have come from suffrage fundraisers, as suffragists were linking their cause to the war effort. This suggests how Freer supported Havemeyer as she fought for women’s rights.

Letters in the Charles Lang Freer Papers show that Freer championed other women, too. On two occasions, Freer hired Detroit ceramicist Mary Chase Perry Stratton (1867–1961) to decorate his Detroit home with her signature Pewabic tiles. Freer encouraged curators at the Detroit Museum of Art to acquire Stratton’s work and promoted Stratton to other art patrons, including Agnes and Eugene Meyer.10 Freer collected the work of painter and interior decorator Maria Oakey Dewing (1845–1927) and took her advice seriously when her husband, painter Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851–1938), decorated his Detroit home in the 1870s. Freer offered collecting advice to Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950), the librarian and curator of banker J.P. Morgan’s library and art collection.11 During Freer’s many visits to Capri in Italy, he wrote to his business partner, Frank J. Hecker, of his admiration for American expatriate artist Romaine Brooks (1874–1970), who lived on the island. Brooks’s androgynous style of dress challenged social conventions at the time and made an impression on Freer.12

These letters reveal how Freer and his female friends were connected to nearly every aspect of the early twentieth-century art world, from the Stieglitz circle in New York to craftswomen like Mary Chase Perry Stratton in Detroit, and from the Asian art market to major art museums and leading scholars throughout the United States and beyond. While highlighting the important roles that women had in establishing the Freer Gallery, this correspondence adds depth to our understanding of how women contributed to the dynamic twentieth-century art world, broadly.