Indian gods and people were a dizzying subject of study for European scholars, East India Company officials, and Christian missionaries, especially during the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century colonial period. Classifying images accompanied by descriptive texts was a popular method for organizing—or satirizing—related information.

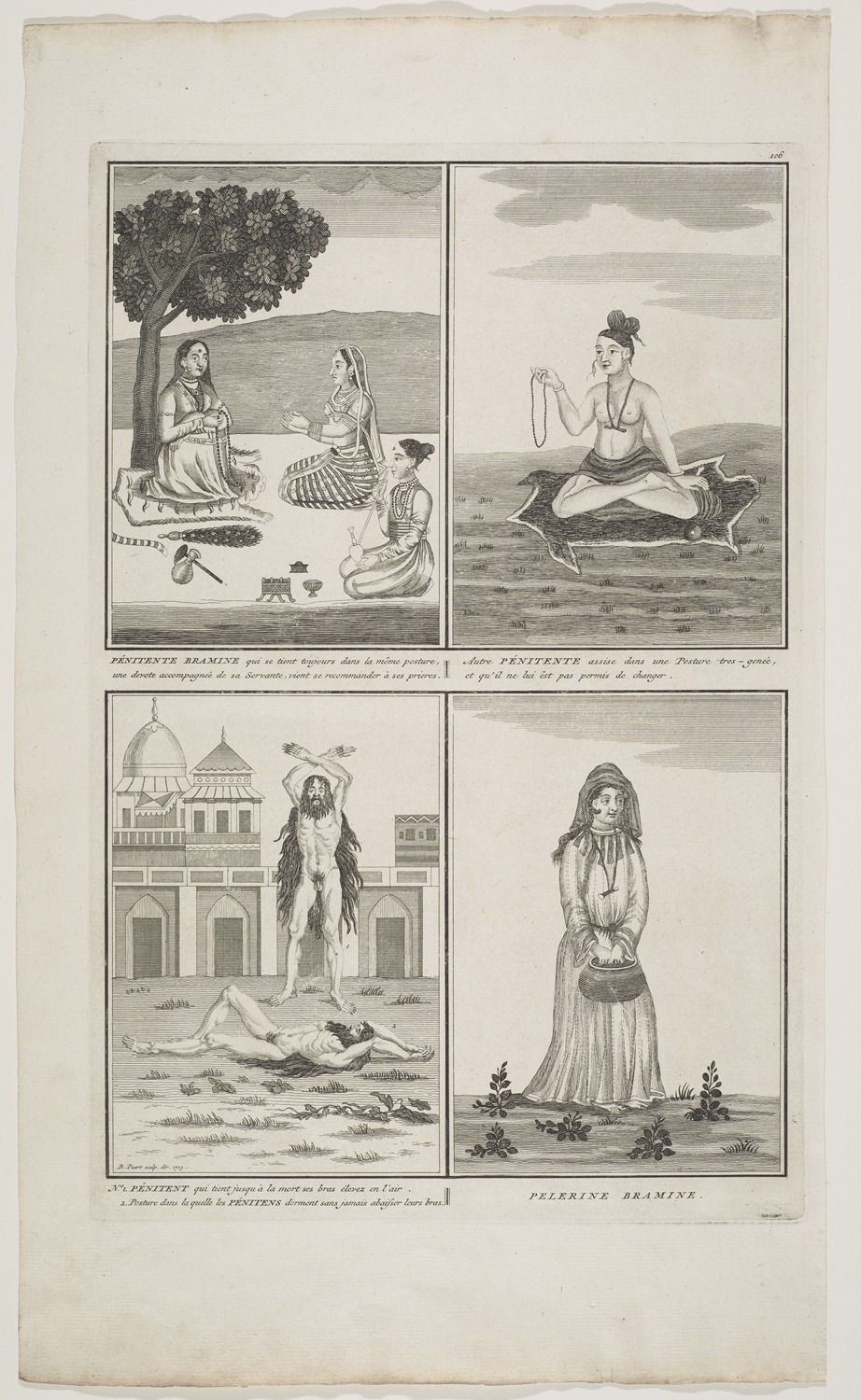

The engraver Bernard Picart consulted Indian paintings for his quarter-page scenes identifying deities and devotees, meant to be an informative resource on a foreign culture. The typology includes the god Brahma, a “she-penitent” in a “very uneasy posture,” and yogis “whose tangled hair … descends lower than their Knees.”

In 1799 in Calcutta, the Belgian artist Balthazar Solvyns published a collection of two hundred and fifty etchings, meant to describe the Indian people’s “manners, customs & dresses.” Europeans in India used these etchings to identify and evaluate the Indian people, perhaps as a means to control them. The collection also became a design source—one that encouraged stereotypes. In his compendium Antique and modern costume, the prolific Italian publisher Giulio Ferrario used Solvyns’ plates of Indian male dress to differentiate the lower, middle, and upper classes in “Various fashions of Indian dress,” and to compare Indian ascetics in “Various types of Fakirs.” Ferrario’s description further reads like a police manual rather than a costume book, differentiating the ascetic “saints” from those who “commit … vexations.”

In a markedly different vein, the satirist Thomas Rowlandson in his 1816 print “Missionary influence…” utilized similar caricatures to condemn Christian missionaries in their attempt to “make converts.” He portrayed “missionary influence” as “intolerance, bigotry, injustice, oppression,” and “vice.”