Antoin Sevruguin and photographic manipulation

Fig.1

Antoin Sevruguin

Pul-i Panjab, Bridge of the “Five Waters” on the Road from Tehran to Mazandaran

Glass plate negative

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.GN.44.04

Image 1 of 14

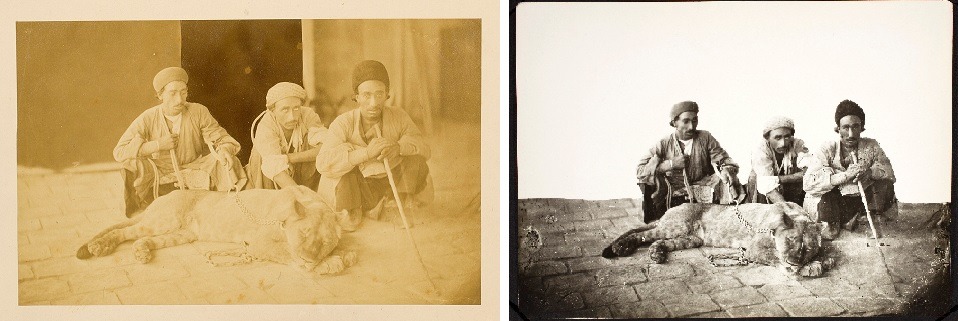

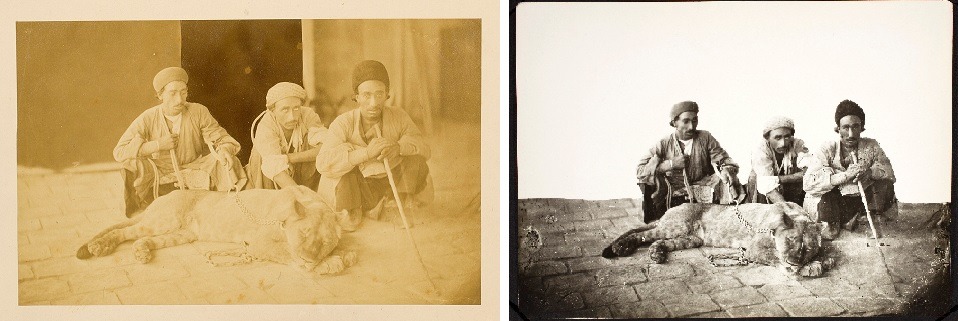

Fig.2

Left, Antoin Sevruguin

Lion Keepers

Albumen print

Stephen Arpee Collection of Sevruguin Photographs

FSA A2011.03 A.01a

Right, Antoin Sevruguin

Lion Keepers

Silver gelatin print

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.Up.11

Image 2 of 14

Fig.3

Antoin Sevruguin

Minaret of Masjid-I Juma, Damghan

Glass plate negative: front, back, and positive print

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.GN.31.08

Image 3 of 14

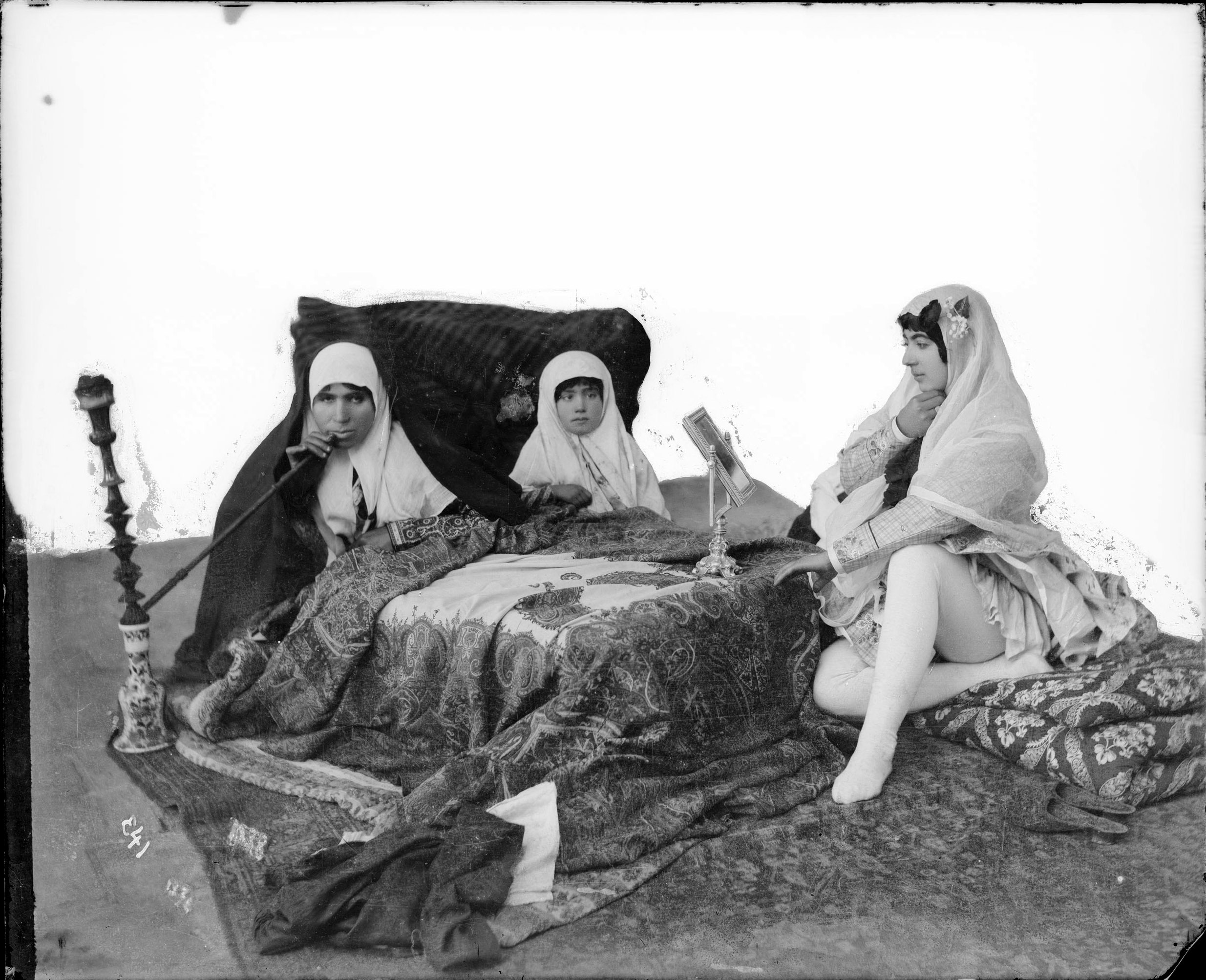

Fig.4

Antoin Sevruguin

Three Persian Women Seated around a Kursi

Glass plate negative

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.GN.43.10

Image 4 of 14

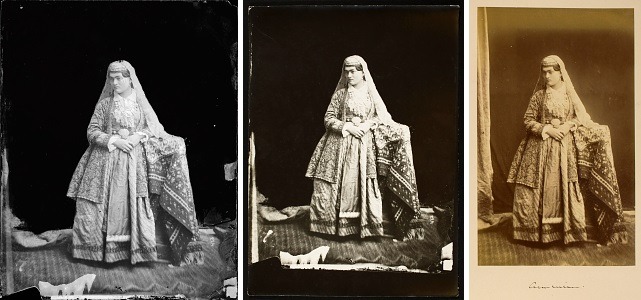

Fig.5

Antoin Sevruguin

Armenian woman

Glass plate negative

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.GN.46.15

-and-

Antoin Sevruguin

Armenian woman

Gelatin silver print

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.Up.33

-and-

Antoin Sevruguin

Armenian woman

Albumen print

Stephen Arpee Collection of Sevruguin Photographs

FSA A2011.03 A.32a

Image 5 of 14

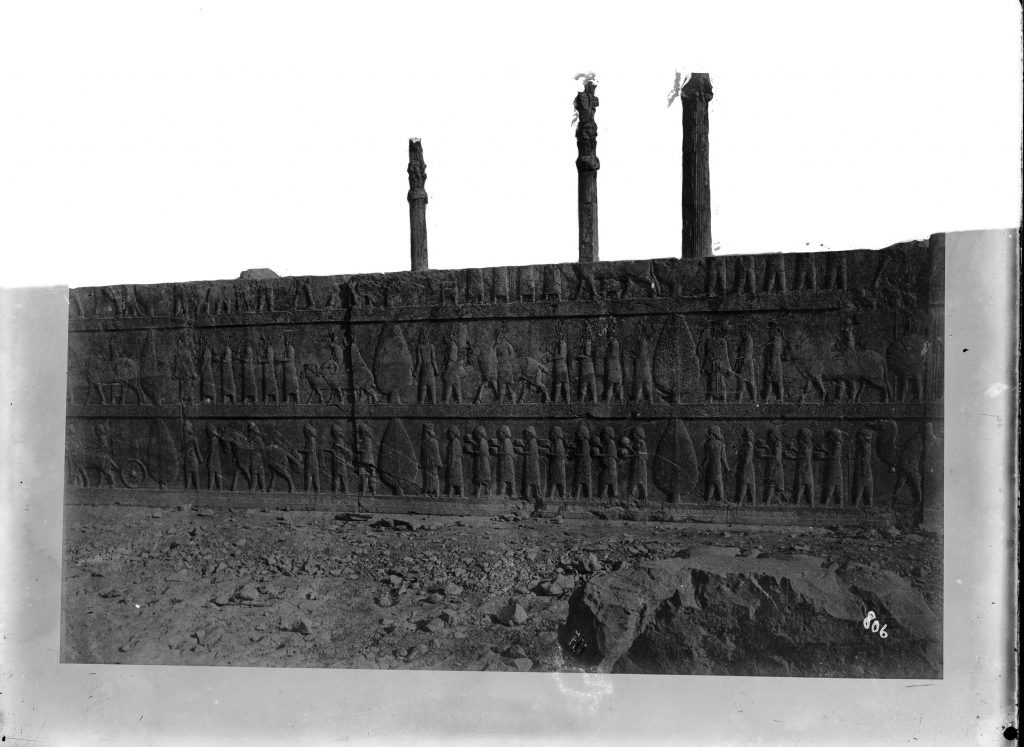

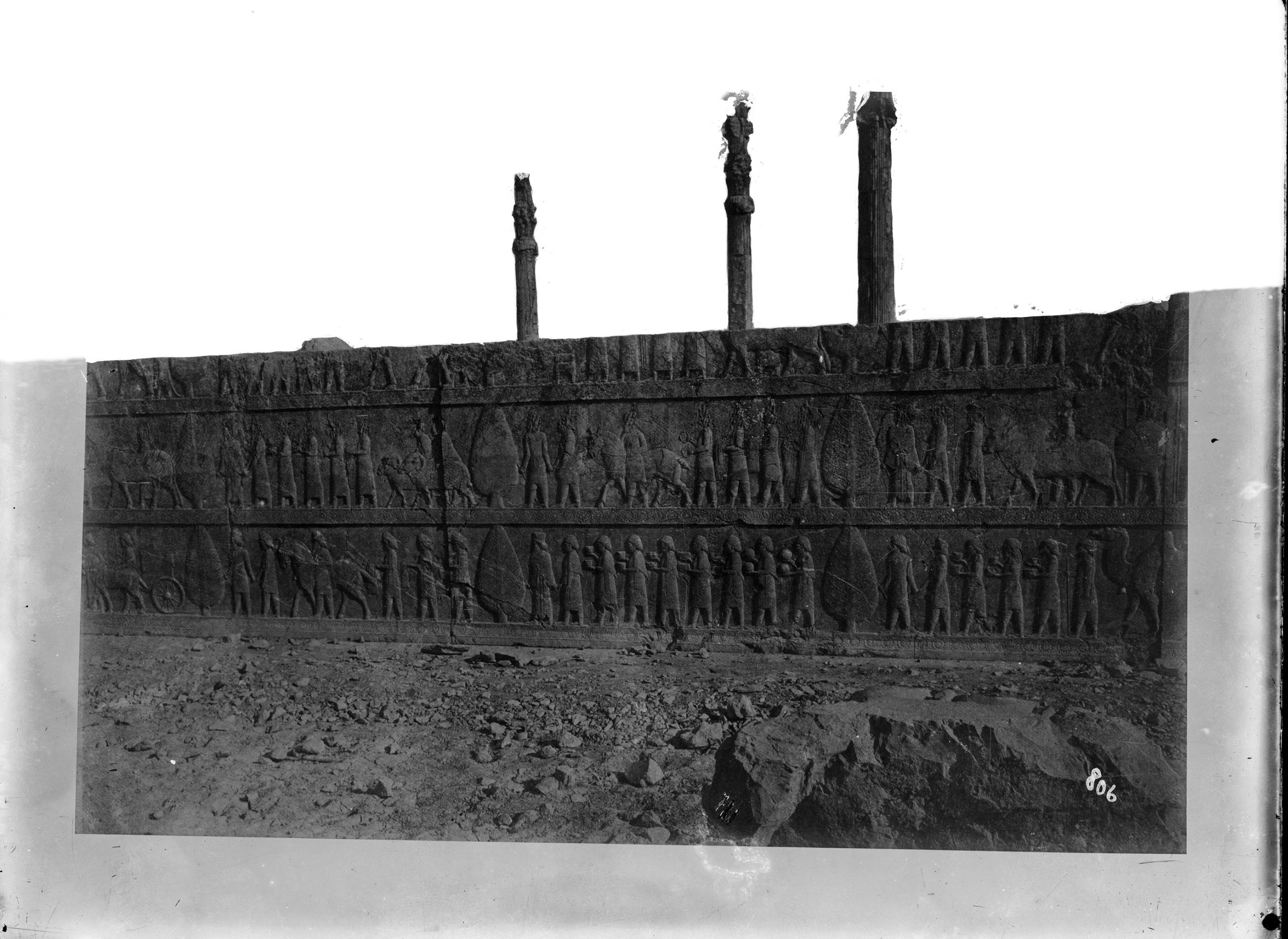

Fig.6

Antoin Sevruguin

Apadana and ceremonial stairway reliefs, Persepolis

Glass plate negative

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.GN.42.07

Image 6 of 14

Fig.7

Antoin Sevruguin

Haruniya Mausoleum, Tus (detail)

Glass plate negative

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.GN.26.09

Image 7 of 14

Fig.8

Antoin Sevruguin

Baharistan Square, Tehran

Glass plate negative

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.GN.48.07

Image 8 of 14

Fig.9

Antoin Sevruguin

Government Gendarmerie

Albumen print

Stephen Arpee Collection of Sevruguin Photographs

FSA A2011.03 A.39a

Image 9 of 14

Fig.10

Antoin Sevruguin

Family portrait

Glass plate negative

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.GN.27.11

Image 10 of 14

Fig.12

Antoin Sevruguin

Officers of the Cossack Brigade

Glass plate negative

FSA A.4 2.12.GN.27.02

Image 12 of 14

Fig.13

Antoin Sevruguin

Family portrait, detail

Glass plate negative

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.GN.27.11

Image 13 of 14

Fig.14

Antoin Sevruguin

Imamzada Hussayn Mosque, Qazvin

Glass plate negative

Myron Bement Smith collection

FSA A.4 2.12.GN.48.05

Image 14 of 14

In the last third of the nineteenth century, when photographer Antoin Sevruguin was at his most prolific level of production, glass plates were the dominant medium used to hold the light-sensitive emulsion needed to capture and retain photographic images. Even after film negatives became available in the late nineteenth century, glass plates remained in use as the preferred medium in professional studios. Although the plates were fragile and heavy, they provided superior image quality and detail. Glass was also an excellent support on which to “retouch” an image before making a final paper print. As a studio procedure, retouching was endemic to photography almost since its inception. Customers who were accustomed to the aesthetic effects routinely seen in paintings desired more idealized images than the new technology produced.

The Myron Bement Smith Papers in the Archives of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery contains 694 glass plates from the Sevruguin studio, dating from the 1870s to the 1930s. Many of them were badly damaged due to the ravages of time, fires, and revolution (fig. 1).

The high-resolution scanning of the entire glass plate collection that was conducted in 2012 revealed Sevruguin and his studio employed an array of retouching techniques. In some cases the Archives has the original glass plate negatives as well as multiple prints of the same image. This makes it possible to discern changes made to the negative over the span of its use by the Sevruguin studio (fig. 2). The variety of retouching techniques used by Sevruguin’s studio not only provides unique insight into the photographer’s methods and intentions, but it also underscores the extraordinary degree of artistic intervention that this trained painter exercised with his prints.

Typically in Sevruguin’s early exterior scenes, the entire sky was masked out by using either black or red ink, or by gluing red paper directly to the surface of the glass plate negative. The red color proved to be effective at masking features from red-spectrum insensitive photographic paper. When paper was glued to the plate, a space was left around landscape features, such as buildings and trees, so a precise silhouette could be applied with ink (fig. 3).

Walls were occasionally masked out for interiors and studio portraits, which sometimes left the figures starkly posed before a white background (fig. 4). In rare cases, backgrounds were partially or entirely rendered solid black by painstakingly scraping off the entire emulsion layer

down to the bare glass (fig. 5). Many plates reveal Sevruguin’s obsessive care in presenting a polished final image, while others show his work was bewilderingly cursory (fig. 6).

On occasion, Sevruguin even removed figures from landscapes (fig. 7). Although he may have preferred to present a landscape devoid of people, more likely he was trying to eliminate the distraction of figures blurred due to moving during long shutter exposures (fig. 8).

In some of his earlier works, Sevruguin carefully etched the bark and branches of trees to enhance their presence as a compositional element in a photograph (fig. 9).

Perhaps the most widely used retouching techniques utilized in nineteenth-century photography studios were smoothing facial features and making areas and details more visible. Sevruguin frequently employed two techniques.

One was to apply varnish to a face to make it brighter than the dark background. Varnish applied over a whole area gave it a subtle halo effect (fig. 10).

The second technique, done in conjunction with varnish, was strategically using a graphite pencil to soften facial shadows and fill in wrinkles. That technique resulted in the appearance of a smooth, young complexion (fig. 11). No portrait sitter was spared this procedure, not even soldiers (fig. 12). In a few cases, Sevruguin scratched into the surface emulsion to lend a sharper expression to the eyes (fig. 13).

While Sevruguin’s techniques were not particularly novel or innovative, the lengths to which he went to achieve a compelling final image are remarkable. The resulting images not only parallel the artistic dedication that marked Sevruguin’s construction of subjects, compositions, and lighting, but they also reflect the rapid embrace of the new medium in Iran in the late nineteenth century.

Note: One unanticipated discovery of digitizing the plates with modern full-spectrum scanning equipment is that the red paint Sevruguin used in masking out parts of the photograph is less effective at blocking light. When digitized, a previously blank sky becomes a vivid canvas of brushstrokes (fig. 14).