Antoin Sevruguin

In the late nineteenth century, Antoin Sevruguin (1840s—1933) managed and operated one of the most successful commercial photography studios in Tehran, Iran. He was born in Iran, but his mother returned with her family to her hometown of Tbilisi, Georgia, after his father, Vassil, a Russian diplomat in Iran, died in a horse-riding accident. Sevruguin trained to become a painter. Accompanied by his two brothers, he returned to Iran in the early 1870s and established a photography studio first in Tabriz and then in Tehran. Sevruguin’s ties to Tbilisi, however, continued through the years. Many of the early portraits of dervishes and women have been simultaneously attributed to Antoin Sevruguin and Dimitri Yermakov, the Georgian photographer who is often referred to as Sevruguin’s mentor.

As early as 1885 many of Sevruguin’s photographs were being published in travelogues, journals, and books. By that time he had a fully established a studio on Tehran’s Ala al-Dawla Street and cemented ties to the court of the Qajar ruler Nasir al-Din Shah (reigned 1848—96). During his lifetime, Sevruguin was often not acknowledged as the source of published images, as in the case of the photographic survey of Persepolis in 1902. On numerous occasions, however, he was celebrated for his artistic vision and his keen eye for composition. He not only received the Medal of Lion and Sun from Nasir al-Din Shah, but he was also awarded Medals of Honor at international expositions held in Brussels (1897) and Paris (1900).

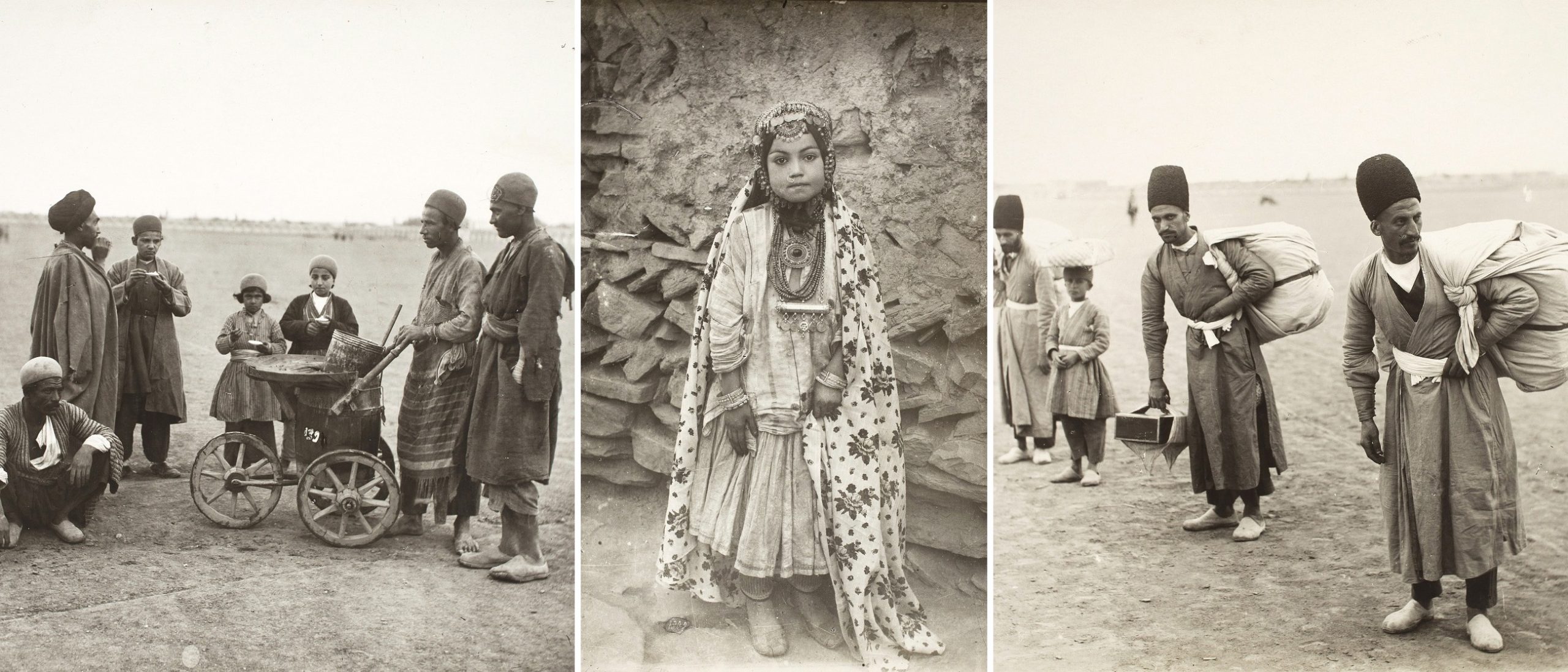

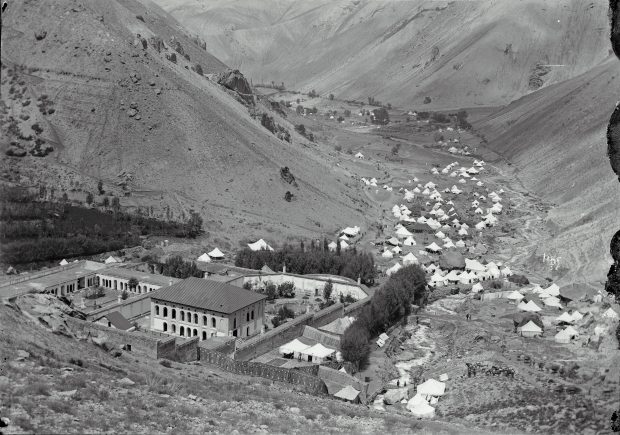

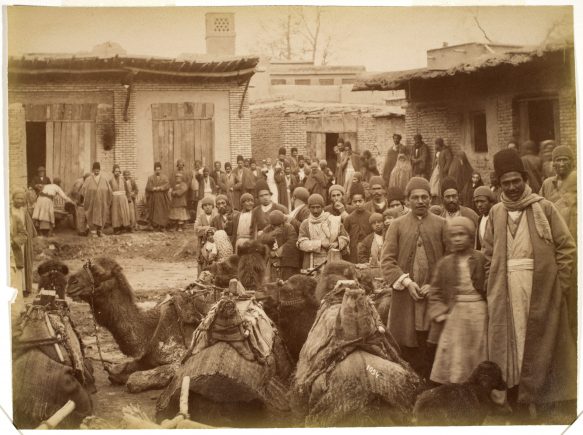

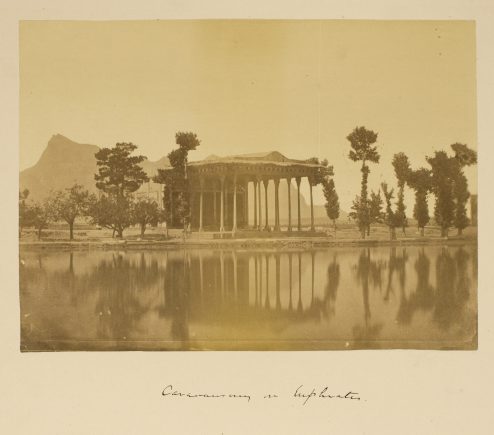

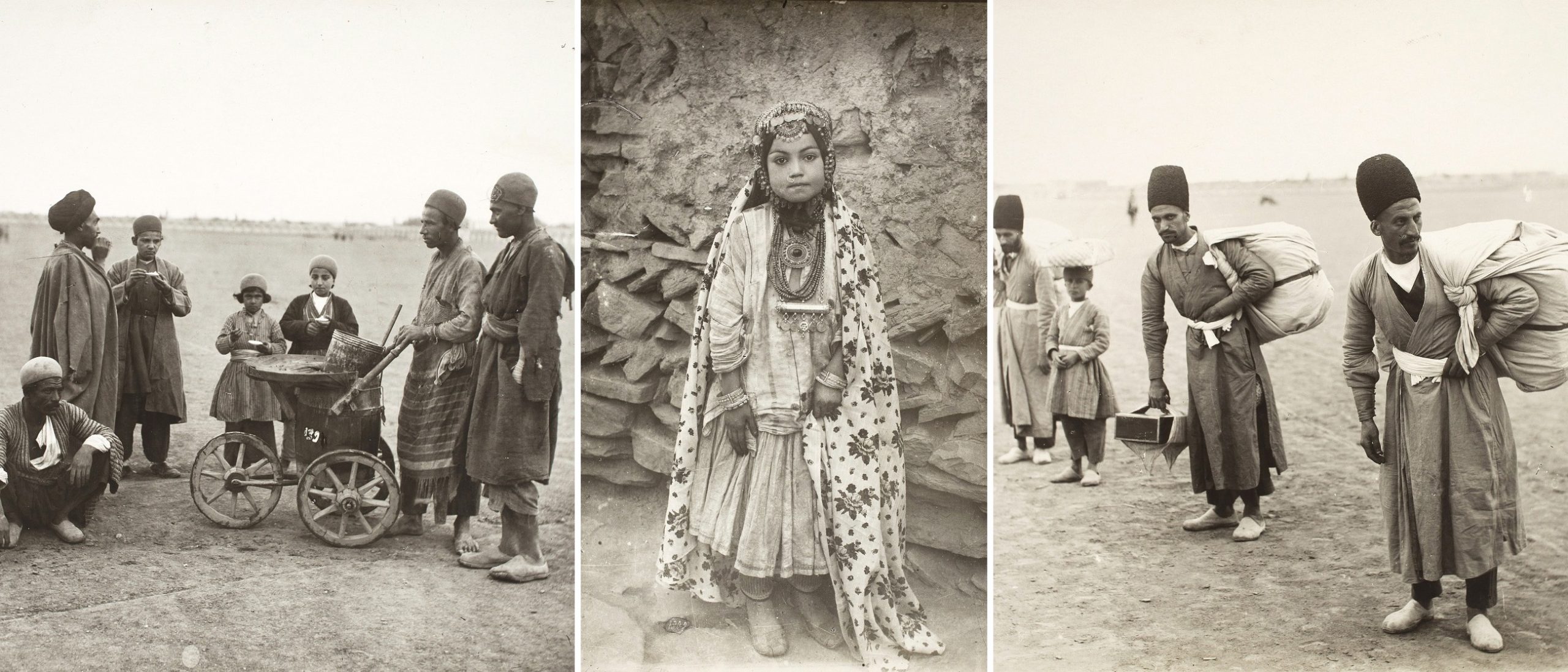

Throughout the five decades of his career, Sevruguin had two pursuits. The first was a desire to record different facets of Iran, and the second was to capture the effect of light in his photographs, emulating the work of painters he admired, including the Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn. The diverse body of Sevruguin’s work includes studio portraits of families, women, and dervishes; survey photographs of archaeological sites, objects, landscapes, and architecture; and photographs of royalty, high-ranking officials, and ceremonies of the Qajar court. The range of his output demonstrates his own pictorial concerns and artistic abilities as well as the divergent interests of his clients.

Numerous devastating incidents occurred throughout his career—the loss of more than half of his glass-plate negatives in a blast and fire in 1908, an unsuccessful attempt to diversify into cinematography in the 1910s, and the confiscation of the remainder of his negatives in the mid-1920s—yet his studio remained in operation even after his death in 1933. Numerous negatives from the Sevruguin studio can be dated to the years after his death, an indication that the studio remained commercially viable. As one of the most prolific early commercial photographers in Iran, Antoin Sevruguin’s artistic legacy endures and reaches new audiences through these online resources.

The National Museum of Asia Art Archives have the largest collection of prints and glass plate negatives by Antoin Sevruguin in a public collection.