Babur voiced strong opinions, both positive and negative, about people in his life.

Friends & Enemies

Friends and Enemies: Baburi

At seventeen, Babur fell for a young male shop attendant. Too bashful for conversation, Babur retreated alone to the hills to write poetry. Although Babur does not describe his crush’s appearance, the round, beardless face and arched eyebrows of this young man exemplify sixteenth-century beauty ideals.

Standing figure with wine cup and flask

Uzbekistan, probably Bukhara, 1550s

Black and red ink with gold on paper

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

Freer Gallery of Art

F1907.764

In the words of Babur…

Babur recounts the tale of his first love, Baburi:

“During this time, there was a boy from the camp market named Baburi. Even his name was amazingly appropriate. I developed a strange inclination for him—rather I made myself miserable over him.

Before this experience I had never felt a desire for anyone, nor did I listen to talk of love and affection or speak of such things. At that time I used to compose single lines and couplets in Persian. I composed the following lines there:

‘May one be so distraught and devastated by love as I; May no beloved be so pitiless and careless as you.’

Occasionally Baburi came to me, but I was so bashful that I could not look him in the face, much less converse freely with him. In my excitement and agitation I could not thank him for coming, much less complain of his leaving. Who could bear to demand the ceremonies of fealty? One day, during this time of infatuation, a group was accompanying me down a lane, and all at once I found myself face-to-face with the boy. I was so ashamed I almost went to pieces. There was no possibility of looking straight at him or of speaking coherently. With a hundred embarrassments and difficulties I got past him. These lines of Salih came to my mind: ‘I am embarrassed every time I see my beloved. My companions are looking at me, but my gaze is elsewhere.’

It is amazing how appropriate this verse was. In the throes of love, in the foment of youth and madness, I wandered bareheaded and barefoot around the lanes and streets and through the gardens and orchards, paying no attention to acquaintances or strangers, oblivious to self and others.

‘When I fell in love I became mad and crazed. I knew not this to be part of loving beauties.’

Sometimes I went out alone like a madman to the hills and wilderness, sometimes I roamed through the orchards and lanes of town, neither walking nor sitting within my own volition, restless in going and staying.

‘I have no strength to go, no power to stay. You have snared us in this state, my heart.’”

Thackston, Wheeler M., trans. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Oxford University Press in association with Smithsonian Institution, Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 1996. 89–90.

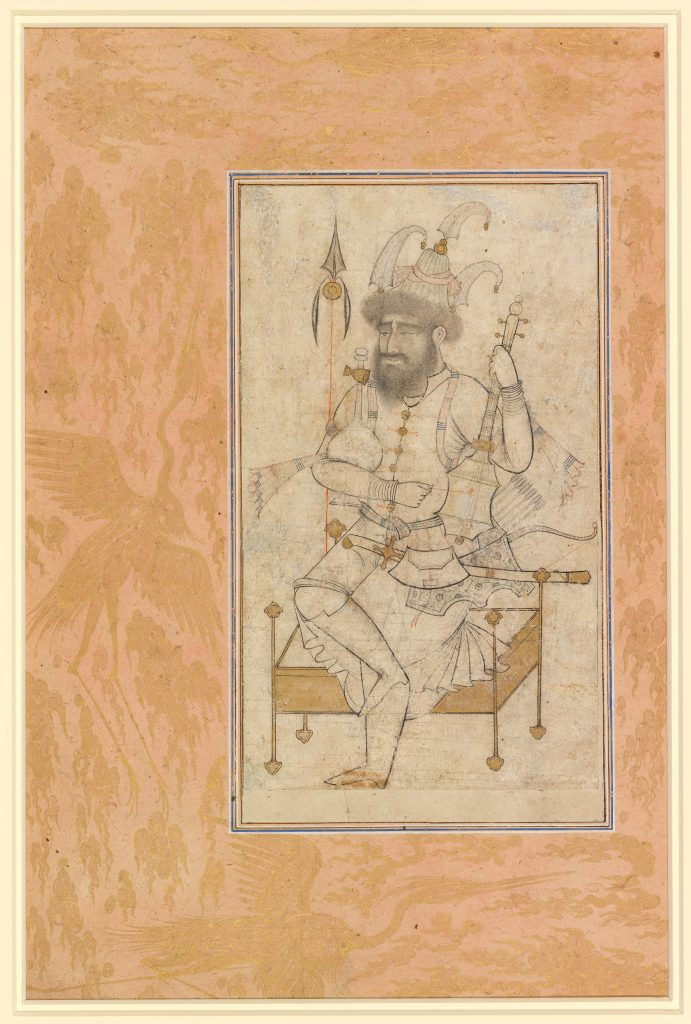

Friends and Enemies: Wormwood Khan

In contrast, Babur harbored a lifelong grudge against his enemies, the Uzbeks, who had ousted him from his ancestral lands. He describes the Uzbek leader “Wormwood” Khan as a crude, vain man who writes pretentious poetry. This caricatured image of an Uzbek ruler, attributed to early sixteenth-century Iran, demonstrates similar sentiments. Greedily clutching a flask while playing a bowed instrument, the figure has heavy features and a bushy beard. But much like the young man, these features are generic traits rather than a study from life.

Caricature of Ubaydallah Khan

Attributed to Aqa Mirak

Iran, possibly Tabriz, ca. 1535

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Lent by The Art and History Collection

LTS1995.2.50

In the words of Babur…

Read Babur’s scathing description of his enemy Wormwood Khan:

“When Wormwood Khan took Herat, he maltreated the princes’ wives and children. Not only with them but also with all the people, even rustics and insignificant little people, he left behind a bad name for his love of this fleeting world. First among his improper deeds in Herat was that for the sake of this filthy world he turned over Khadija Begim to Shah Mansur Bakshï’s wife for safekeeping and let her be tormented in all sorts of ways. He had the Moghul Abdul-Wahhab hold a saintly person like Shaykh Puran prisoner, and each of Shaykh Puran’s sons was handed to a different person. All the poets and literati were put in Mulla Banna’I’s charge. In this connection the following occasional piece became famous among the wits of Khurasan:

‘Except for Abdullah the donkey’s prick no poet today has seen the face of gold. / Banna’I craves gold from poets: perhaps he will get the donkey’s prick.’

As soon as Wormwood Khan seized Herat he married Muzaffar Mirza’s wife, Khanzada Khanïm, without waiting for the prescribed interval to elapse. His illiteracy notwithstanding, [Wormwood Khan] presumed to give lessons in Koranic interpretation to Qazi Ikhtiyar and Muhammad Mir Yusuf, who were among Herat’s renowned and talented mullas. To the calligraphy of Sultan-Ali Mashhadi and the painting of Bihzad he took his pen and made corrections. Moreover, every few days he would compose insipid poetry and have it recited from the pulpit and hung in the marketplace to receive accolades from the populace. He rose with dawn and never neglected the five daily prayers, and knew how to recite the Koran well, but he nonetheless said and did a multitude of stupid, imbecilic, audacious, and heathenish things.”

Thackston, Wheeler M., trans. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Oxford University Press in association with Smithsonian Institution, Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 1996. 249.

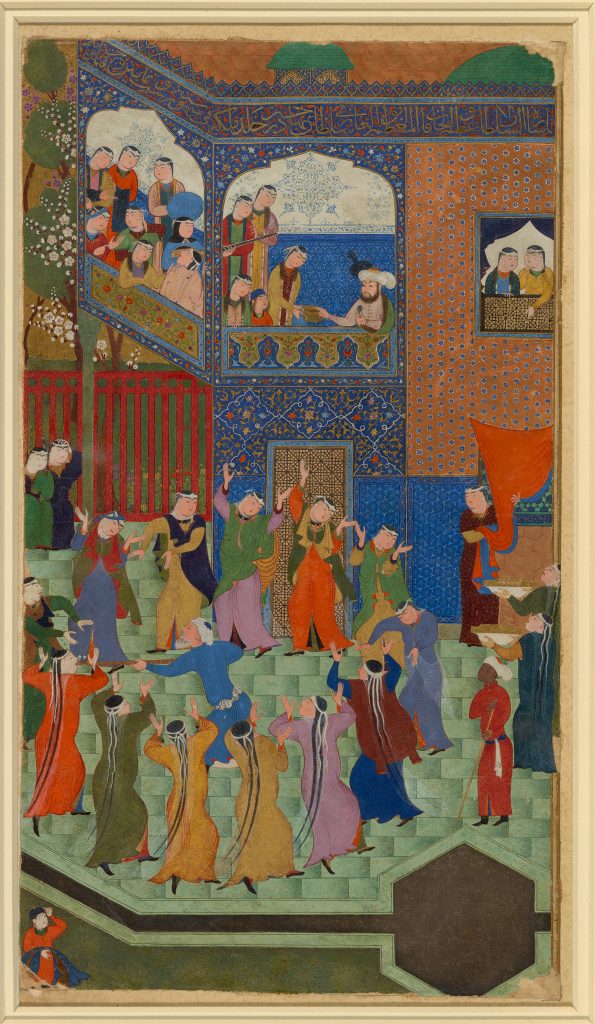

The Women in His Life

In Babur’s memoirs, we learn that he sought advice from female relatives; humbly obeyed his mother; and dithered, at least sometimes, in matters of romance. Although these episodes are rarely illustrated, they are evoked in paintings from Babur’s lifetime.

The first painting depicts the harem of Babur’s ancestor Sultan Husayn Mirza Bayqara. Surrounded by his favorites, the ruler observes a female dance troupe from above as a servant offers wine in a decorated bowl. A similar bowl, once owned by Sultan Husayn Mirza Bayqara, may be seen in the Diplomacy section.

The wedding night scene illustrates a romance. The tentative body language of the central figures mirrors Babur’s frank description of his first marriage at age seventeen. Babur recounts that he was so shy around his wife that his mother was forced to intervene “with the severity of a quartermaster,” making him visit her every month.

Harem of Sultan Husayn Mirza Bayqara

Attributed to Shah-Muzaffar

Historic Iran, present-day Afghanistan, Herat, 1481 (AH 886)

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Lent by The Art and History Collection

LTS1995.2.142

In the words of Babur…

Babur describes his shyness with his first wife:

“Sultan-Ahmad Mirza’s daughter Ayisha Sultan Begim, who had been affianced to me while my father and uncle were still alive, came to Khodzhent, and we were married in the month of Sha‘ban [March 1500]. In the early days after the wedding, although my affection for her was not lacking, since it was my first marriage and I was bashful, I went to her only once every ten, fifteen, or twenty days. Later on, I lost my fondness for her altogether, and I was still shy. Once every month or forty days my mother the khanïm drove me to her with all the severity of a quartermaster.”

Thackston, Wheeler M., trans. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Oxford University Press in association with Smithsonian Institution, Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 1996. 89.

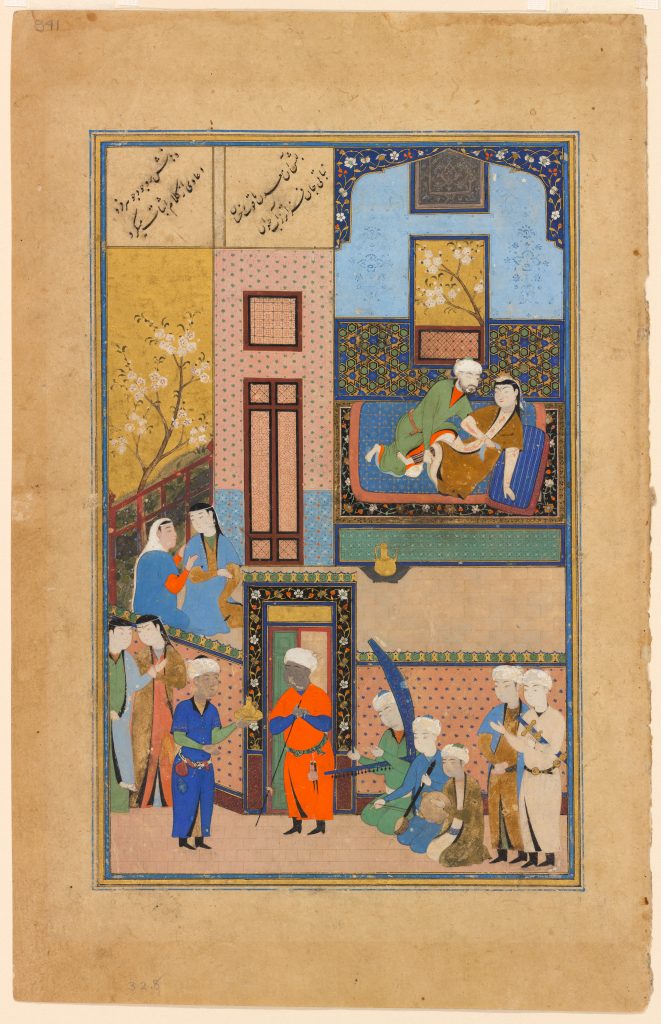

Folio from a Mihr-u Mushtari (The Sun and Jupiter) by Assar Tabrizi

Uzbekistan, Bukhara, Shaybanid dynasty, 1523–24 (AH 930)

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment

Freer Gallery of Art

F1932.8

In the words of Babur…

Babur describes his shyness with his first wife:

“Sultan-Ahmad Mirza’s daughter Ayisha Sultan Begim, who had been affianced to me while my father and uncle were still alive, came to Khodzhent, and we were married in the month of Sha‘ban [March 1500]. In the early days after the wedding, although my affection for her was not lacking, since it was my first marriage and I was bashful, I went to her only once every ten, fifteen, or twenty days. Later on, I lost my fondness for her altogether, and I was still shy. Once every month or forty days my mother the khanïm drove me to her with all the severity of a quartermaster.”

Thackston, Wheeler M., trans. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Oxford University Press in association with Smithsonian Institution, Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 1996. 89.