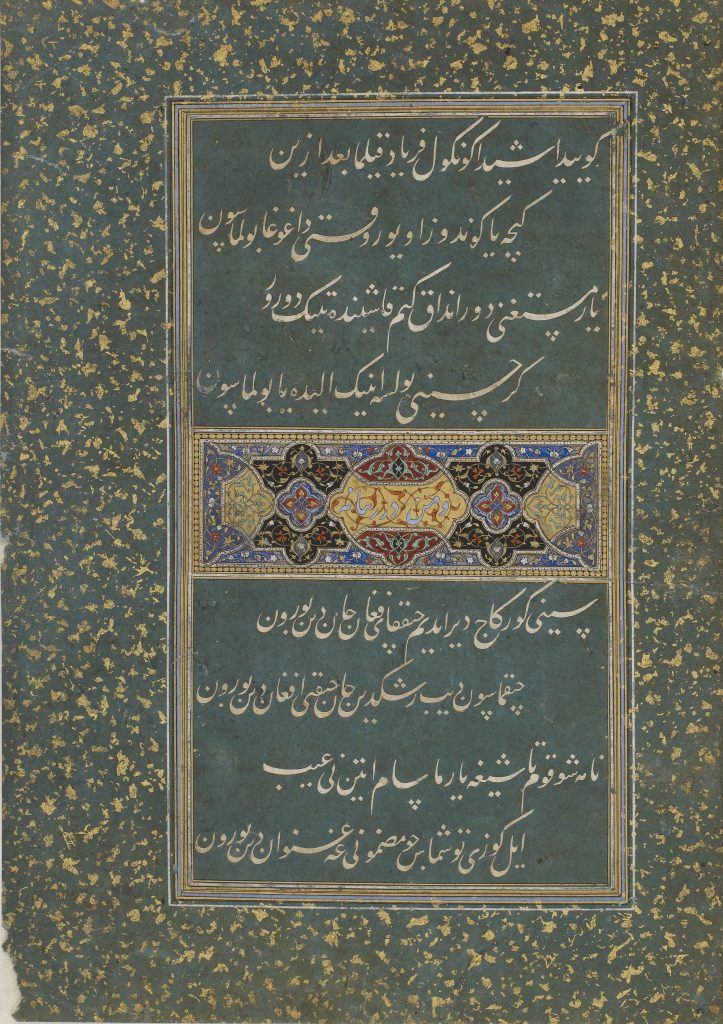

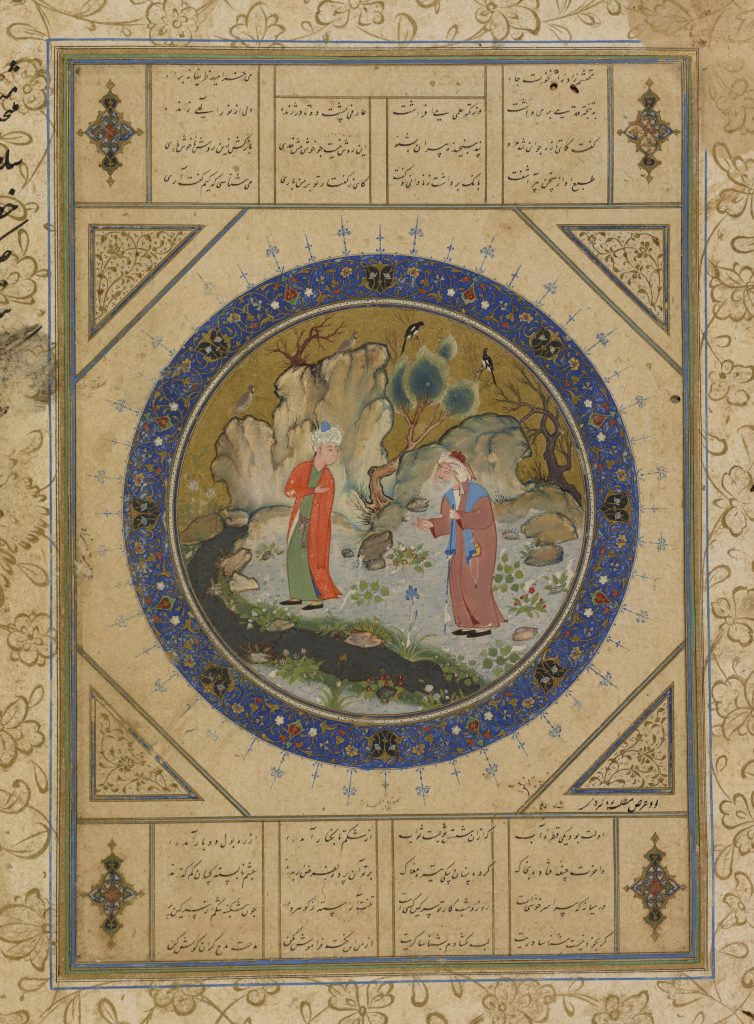

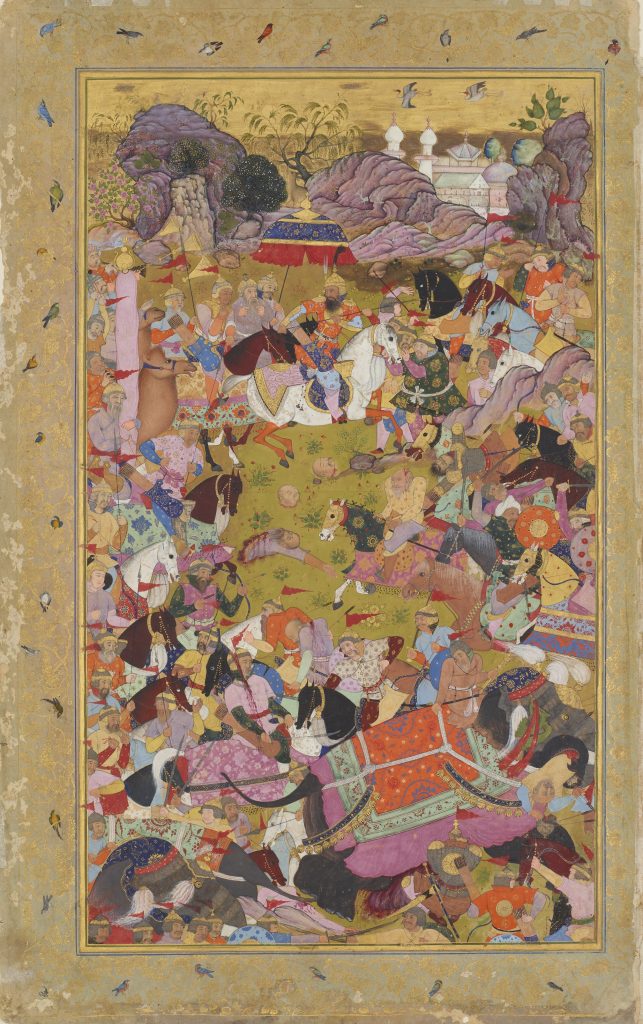

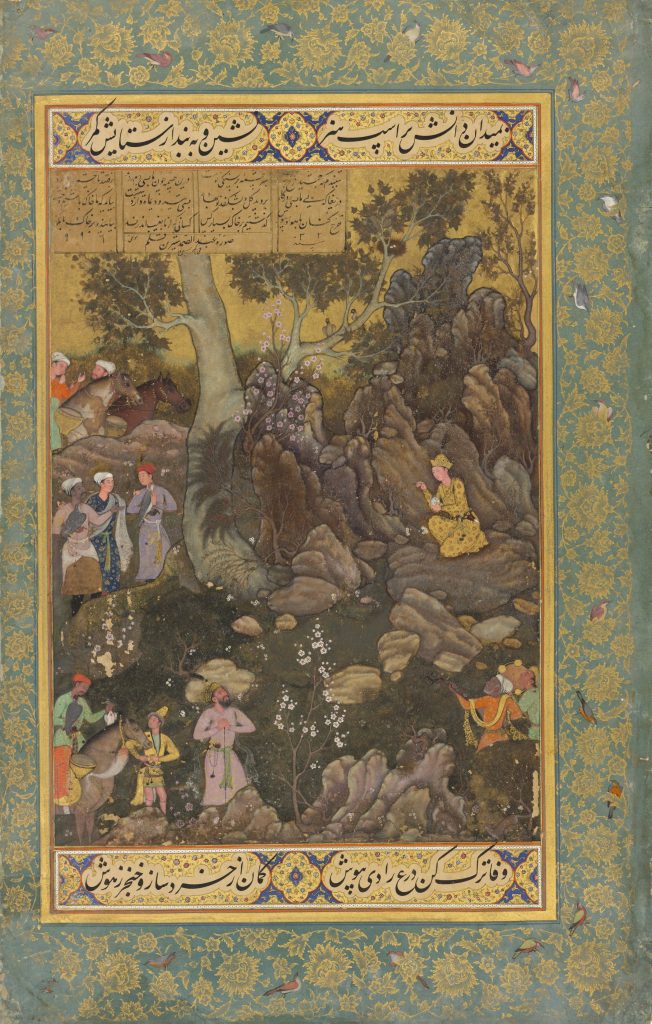

Babur was a Timurid, a descendant of the Central Asian ruler Timur who, in the thirteenth century, conquered a vast territory stretching across Asia. The Timurids, whether scrappy princes with small realms or great rulers, were enthusiastic patrons of the written word. They built libraries, commissioned richly illuminated and illustrated manuscripts, and wrote poetry. This culture shaped Babur’s early experiences with art and literature, and his appreciation for these traditions shows up throughout his candid prose.

Babur’s descendants became known as the Mughals after his maternal ancestor, the Mongol Genghis Khan, whose descendants reigned over much of the region from the mid-thirteenth century to the mid-fourteenth century. However, the Mughals most closely identified with their Timurid heritage. They continued this legacy by commissioning their own copies of the poems and stories known to Babur.