September 24, 2011–January 29, 2012

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

Chinese Art

From the 1860s until her death, the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908) was the dominant political figure of China’s Qing dynasty (1644–1911), acting as regent to two successive emperors. During her reign, the Qing court came to be regarded as conservative, corrupt, and incompetent. The situation worsened after the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, when Cixi was accused of encouraging the killing of foreigners and Chinese Christians. Her reputation plummeted in China and worldwide.

In response, the Qing court initiated measures to improve the Empress Dowager’s image. Along with inviting foreign visitors to receptions at the palace, these efforts included arranging for a series of photographic portraits of Cixi, some of which were presented as diplomatic gifts. Taken by a young photographer named Xunling (ca. 1880–1943) between 1903 and 1904, the series comprises the only surviving photographs of the Empress Dowager. The National Museum of Asian Art Archives contains thirty-six of Xunling’s original glass-plate negatives, which form the basis of this exhibition.

Though dismissed as emblems of Cixi’s vanity and the Qing dynasty’s extravagance, the photographs became an enduring symbol of the dying reign and helped form the “dragon lady” persona seen in films throughout the twentieth century. But closer examination of the photographs reveals many of them were crafted as part of a strategic diplomatic and public relations campaign. Analysis of carefully placed symbols found within these images has provided new insight into the Qing court culture, as well as the Empress Dowager’s public and private life.

This exhibition has received support from the Lodestar Fund and generous individuals.

Explore the Exhibition: Throne

Throne

Cixi first wanted her photograph taken in a setting that replicated the reception hall, as if she were in formal audience. In other words, her priority was to convey her authority and legitimacy as head of state.

The photographs in the Throne series feature the Empress Dowager alone before a standing screen, with an overhead banner proclaiming her full title. Despite this repetitive composition, the images display surprising variety. Cixi adopts a vivid array of poses, costumes, and props, each with a different meaning and objective.

Symbols

Cixi’s embroidered robes are rich with traditional Chinese emblems of longevity—for herself and, by extension, for the Qing dynasty. This robe is covered with stylized longevity characters, as well as butterflies, considered a metaphor for long life.

Longevity

Gold-painted longevity character. Detail from Portrait of Tzu-Hsi (Cixi), Empress Dowager of China

Fruit

Flanking Cixi are carefully stacked mounds of fruit. Cixi was not fond of incense and so used fresh fruit to sweeten the air, but these apples may have had a more important purpose. While not a traditional feature of Chinese art, the Chinese term for apple is a homonym for peace. The use of Western apples in the photos may have been a subtle message of conciliation to the foreign powers occupying Beijing after the Boxer Rebellion.

Table & Shawl

Cixi’s gold filigreed fingernail covers were traditionally worn in the Qing court, as were her “horse-hoof” shoes. While maintaining such conventions, in this image Cixi also included a French Louis XIV pedestal table, upon which rests an embroidered Indian paisley shawl. The arrangement may have refuted her reputation as an insular, xenophobic ruler.

Explore the Exhibition: Diplomacy

Diplomacy

The Qing court took on an unprecedented level of diplomatic engagement after the Boxer Rebellion, an attempt to improve relations with key foreign nations. This strategy included presenting photographic prints of Cixi as diplomatic gifts.

Gifts

This large painted portrait was delivered to Washington, DC, in 1904 as a gift for President Theodore Roosevelt. The image’s surface is lavishly tinted, with minute details highlighted in brilliant gold paint. The effect is one of regal authority, while the subject’s close proximity and direct gaze lend a sense of personal affinity—perhaps just the combination Cixi believed would be most effective in communicating with a fellow head of state.

Gifts

In the summer of 1905, a group of congressmen and their families traveled on a three-month diplomatic tour of Asia, led by Secretary of War William Howard Taft. Among the most publicly notable members of the Taft Mission was President Roosevelt’s daughter Alice (1884–1980). Much was made in the press about the meeting between the young, glamorous daughter of the president and the aged symbol of the conservative Qing court.

In her 1933 autobiography, Alice described her meeting with Cixi in vivid detail, but placed more emphasis on receiving this photograph of the Empress Dowager the following day. “A troop of cavalry clattered down the street to the Legations,” she recalled, “surrounding an imperial yellow chair in which, by itself, was the photograph.” This dramatic presentation indicates that, rather than mere memento, the photograph was intended as an extension of Cixi’s imperial presence.

Diplomatic Women

In a bold step, starting in 1902 Cixi hosted a series of social gatherings at the palace for the ladies of the legations, based on the assumption that women would be more amenable to appeals of friendship. Less than two years had passed since the legation quarters had been bombarded by Boxers and imperial troops, and resentment toward the Qing court and Cixi in particular still ran high.

But the effectiveness of this strategy soon became apparent. Cixi’s graciousness at social functions was duly reported to the press, making a positive impact on her international reputation.

Sarah Pike Conger

The woman holding Cixi’s hand is Sarah Pike Conger (ca. 1843–1932), wife of the American minister to Beijing. Conger wrote movingly of Cixi’s many virtues in newspaper articles and books.

Explore the Exhibition: Private Moments

Private Moments

Among the glass plates in the National Museum of Asian Art Archives are nine small negatives showing Cixi and her attendants, mostly among the snowy gardens of Wanshoushan (Longevity Hill), the central hill of the Summer Palace. Many photographs in this series have never been published and are presented for the first time in Power|Play. They were not distributed or used as gifts. These images were likely intended for Cixi and her attendants’ personal enjoyment, rather than the Qing court’s diplomatic efforts.

Imperial Assistants

In many of the photographs, Cixi is shown with various ladies and eunuchs. Some were assistants who constantly attended to the Empress Dowager, helping her in every activity from dining to bathing. Many were also friends, trusted confidantes, and even valued political advisors.

The women in the photographs range from anonymous relatives to imperial consorts second in rank only to Cixi herself. The fourth daughter of Prince Qing, a secondary prince who rose to power by marrying Cixi’s cousin, was considered one of the great beauties of the court. She also was one of the Empress Dowager’s closest attendants.

The Yugeng Family

Cixi is flanked by the photographer’s sisters, Deling and Rongling. Behind them is their mother, Madame Yugeng.

The most frequently visible of Cixi’s assistants are Xunling’s sisters, Deling (1885–1944) and Rongling (1882–1973), and their mother, Madame Yugeng (dates unknown). The early history of the family is fairly obscure. We do know that Xunling’s father was made ambassador to Tokyo in 1895 and to Paris in 1899. The Yugeng children grew up exposed to an international array of languages, arts, and societies. Deling and Rongling, for example, studied acting under Sarah Bernhardt and dance under Isadora Duncan, while Xunling pursued photography.

Under the Boxer Protocol of 1901, Cixi and her court were required to hold direct audiences with foreign ambassadors and visiting dignitaries. The court rushed Yugeng and his family home from Paris to help. The Yugengs’ fluency in foreign languages and knowledge of Western propriety made them critical to Cixi as intermediaries and translators, and as advisors in etiquette and diplomatic protocol.

Cixi and Deling

This negative was copied from a well-worn mounted print, likely at the request of Deling, who was intent on demonstrating to American audiences her close friendship with the Empress Dowager. As an author and speaker in the United States, Deling’s reputation rested on the credibility of her tale about having once been Cixi’s favorite attendant. She no doubt cherished this portrait.

Explore the Exhibition: Tableaux, The Power of Play

Tableaux

Cixi was an enthusiastic advocate of theater arts. She commissioned new libretti and updates of traditional dramas, and she organized a personal acting troupe composed of court eunuchs. In this group photograph, Cixi assumes a theatrical pose.

Love of Theater

This is perhaps the most enduring yet enigmatic of Cixi’s photographic portraits. She gazes into a mirror while placing a flower in her hair—a pose that may represent her love of theater. A pivotal scene in the Ming dynasty play The Peony Pavilion features the heroine, Du Liniang, gazing at her own beauty in a mirror as her maid adorns her hair with a flower. In recorded versions of the play, this scene is strikingly similar to Cixi’s portrait.

Portraying Piety

In one series of images—taken in the summer of 1903 at Zhonghai, a lake west of the Forbidden City—Cixi adopts the role of Guanyin, the Buddhist bodhisattva of compassion. She sits near an array of potted lotuses, before a painted backdrop of the Purple Bamboo Grove of Guanyin. Her attendants adopt the guises of the bodhisattva’s attendants.

Cixi’s portrayal of herself as a divinity may seem egotistical to modern audiences. However, new research has shown that, at the end of the fifteenth century, some Chinese women dressed and styled their hair like Guanyin as a show of piety. Rather than trying to personify the bodhisattva, Cixi was participating in a popular act of devotion.

Broad Benevolence

In front of Cixi is a bronze vessel with a slip of paper that states “Ningshougong” (Palace of Tranquil Longevity). Ningshougong was a complex built within the Forbidden City for the retirement of the Qianlong Emperor (reigned 1711–99) and later given over for Cixi’s use. As Cixi highly respected Qianlong’s legacy, the label was meant as homage to the late ruler.

Rising out of the bronze vessel is the character for longevity, stylized into a wisp of smoke. High-resolution scans reveal three previously unreadable characters on top of this one. Together the characters spell Guangrenzi, or “Broad Benevolence,” which was Cixi’s title conferred by a major Daoist temple in Beijing.

The theatrical references, political allegiances, religious titles, and symbols of longevity establish these scenes as more than casual photo shoots. Cixi was using the camera to record the values of the imperial court. The photographs also emphasize her own religious and political legitimacy during the court’s final years.

Explore the Exhibition: Cixi’s Popular Legacy

Popular Legacy

Soon after their production, copies of Cixi’s photographs were sold in the streets of Chinese cities. Qing officials may have encouraged their distribution, or they may have been unable to prevent them from leaking out. In any case, the portraits did little to improve Cixi’s reputation. In the West, the image of a female ruler in theater garb merely confirmed the suspicion that the Qing court was too out of touch to endure in the modern era.

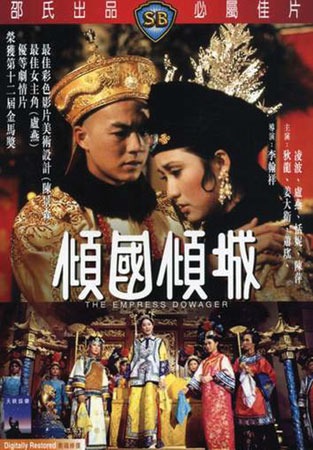

Cinematic Works

Cixi fared even more poorly in cinematic works. Chinese films, such as Sorrows of the Forbidden City (1948), depicted her as a scheming harridan who suppresses the emperor and murders innocent concubines. In Hollywood, over-the-top characterizations of the Empress Dowager as a wicked Asian “dragon lady” became a staple, culminating in such performances as Flora Robson’s “yellow face” rendering in the 1963 film 55 Days in Peking.

Recent Portrayals

Popular culture is still struggling with the historical image of Cixi. Only in the last few decades of film, theater, and television has a more complex version of the Empress Dowager emerged. In the darkly haunting cameo by Lisa Lu in the Bernardo Bertolucci film The Last Emperor (1987), viewers are presented with a still-menacing but more humane Cixi. In Li Lianying, the Imperial Eunuch (1991), she is a nuanced and even sympathetic figure. Though still portrayed as xenophobic and selfish, Cixi now is seen with a vulnerable and empathetic side as well.

Symposium

Freer Gallery of Art

Meyer Auditorium

December 5–6, 2011

Coinciding with the Sackler exhibition Power|Play: China’s Empress Dowager, this symposium examined imperial portraiture during the advent of photography in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

While Power|Play addressed the unique circumstances and intentions behind photographs of Empress Dowager Cixi, the symposium was an opportunity for a broader comparative analysis of the engagement with photography in ruling courts across Asia. Among other topics, scholars considered how photographs of court figures were used to create images of power, to establish a sense of nationhood, and to express a religious identity, as well as the relationship between early photographic representations and more recent imperial images from the region.

Invited speakers included Ali Behdad, John Clark, Deepali Dewan, Holly Edwards, Maki Fukuoka, Luke Gartlan, Yi Gu, Christine Kim, Yuhang Li, Hyung Il Pai, Maurizio Peleggi, Ying-chen Peng, Claire Roberts, Mary Roberts, and Roberta Wue. Visit the links below to learn more about the speakers and their presentations.

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2011

Yi Gu, University of Toronto

Prince Chun through the Lens: Negotiating Photographic Medium in Royal Image

Ying-chen Peng, University of California, Los Angeles

Lingering between Tradition and Innovation: Photographic Portraits of Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908)

Ali Behdad, University of California, Los Angeles

Portrait Photographs: Constructions of Masculinity; Representations of Power

Luke Gartlan, University of St. Andrews

The Reverent and the Everyday: Presenting Imperial Photographic Portraits in Meiji Japan

Hyung Il Pai, University of California, Santa Barbara

Romancing the Ruins of Imperial Antiquity: Travel Myths, Memories, and the Marketing of Heritage Destinations in Korea

Roberta Wue, University of California, Irvine

The Mandarin at Home and Abroad: Picturing Li Hongzhang (1823–1901)

John Clark, University of Sydney

Presenting the Self: Pictorial and Photographic Discourses in Nineteenth-century Dutch Indies, Siam, and Japan

Deepali Dewan, Royal Ontario Museum, University of Toronto

Embellished Reality: Paint and Photography in Studio Portraiture from India

Mary Roberts, University of Sydney

Ottoman Statecraft and the “Pencil of Nature”: Portrait Photography and Drawing at the Court of Sultan Abdülaziz

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 6, 2011

Maki Fukuoka, University of Michigan

Pictorializing the Emperor

Yuhang Li, Yale University

Mimicking Guanyin through the Lens: Cixi/Guanyin Photographs

Claire Roberts, Australian National University

Chinese Imperial Portrait Photography: Reconciling Heaven and Earth

Holly Edwards, Williams College

Timely Portraits: Afghan Women Then and Now

Christine Kim, Georgetown University

Portraying Korea’s Colonial Monarchy: Images of Assimilation and Modernity

Maurizio Peleggi, National University of Singapore

From Image to Icon: The Aesthetics and Politics of Thai Royal Portraiture

Ali Behdad is the John Charles Hillis Professor of Literature and chair of the English Department at the University of California, Los Angeles. He has published widely on a broad range of topics, including Orientalism, travel literature, nationalism and immigration in the United States, and the history of photography in the Middle East. He is the author of Belated Travelers: Orientalism in the Age of Colonial Dissolution (1994) and A Forgetful Nation: On Immigration and Cultural Identity in the US (2005). He is currently completing a book manuscript on Orientalist photography.

John Clark, CIHA, FAHA, is professor of Asian art history and an Australian Research Council (ARC) Professorial Fellow at the University of Sydney. Among his recent books are Asian Modernities: Chinese and Thai Art of the 1980s and 1990s (Sydney: Power Publications, 2010) and Modernities of Chinese Art (Leiden: Brill, 2010). He wrote “The Southeast Asian Modern” in the anthology Modern and Contemporary Southeast Asian Art, edited by Nora Taylor and forthcoming from Cornell University Press; and “Okakura Tenshin and Aesthetic Nationalism” in Japanese Art of the Modern Age, edited by Thomas Rimer and forthcoming from the University of Hawai’i Press.

Deepali Dewan is an art historian of South Asian visual culture. She holds a PhD from University of Minnesota and a BA (Honors) from McGill University, Montreal. She is currently curator at the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, and teaches in the Department of Art at the University of Toronto with an affiliation with the Centre for South Asian Studies. Her research encompasses nineteenth- and twentieth-century visual culture of South Asia and the South Asian Diaspora, with particular emphasis on the impact of colonialism, nationalism, and modernity on knowledge production. For the last decade, her research has focused on the history and theory of photography in India. She coauthored a book on nineteenth-century photographer Raja Deen Dayal, which is forthcoming from the Alkazi Collection of Photography and Mapin. In addition, she edited Bollywood Cinema Showcards: Indian Film Art from the 1950s to the 1980s (2011) and authored Embellished Reality: Indian Painted Photographs (forthcoming). Dewan is part of the Toronto Photography Seminar, a multidisciplinary group that has received a number of grants to organize conferences, guest-edit volumes, and invite speakers on the topic of photographic history. She has received fellowships from the Social Science Research Council, the American Institute of Indian Studies, the College Art Association, and the MacArthur Program/Interdisciplinary Center for the Study of Global Change.

Holly Edwards holds degrees from Princeton University, University of Michigan, and New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. She is senior lecturer in the Art Department at Williams College, where she offers courses on the art and architecture of the Islamic world. Her research interests presently center on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, ranging from American Orientalism to Afghan photography. Her publications encompass a broader array of topics: commemorative architecture in the Indus Valley, architectural epigraphy, and contemporary painting. She has curated two major exhibitions, Noble Dreams, Wicked Pleasures: American Orientalism 1870–1930 (catalogue printed by Princeton University Press, 2000) at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute; and, with Mark Reinhardt and Erina Duganne, Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain (University of Chicago Press, 2007) at the Williams College Museum of Art.

Maki Fukuoka is assistant professor of Japanese humanities at the Department of Asian Languages and Cultures, University of Michigan. Fukuoka focuses on visual culture of nineteenth-century Japan with a particular emphasis on photographic representations and technology. She is interested in tradition and modernity in Japan and how their conflicting and often confusing relationships are represented or articulated visually. In this light, her purview extends to the formulation of Japanese art history as well as relationships between exhibition practices and the dissemination of knowledge in modern Japan. Her book The Premise of Fidelity: Science, Visuality, and Representing the Real in Nineteenth-Century Japan will be published by Stanford University Press in spring 2012. She is currently working on a new project called Shaping a Likeness that explores the roles and uses of portrait photographs in early Meiji Japan.

Luke Gartlan is a lecturer in the School of Art History at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland. He guest-edited special issues on photography in nineteenth-century Japan for the journal History of Photography (May 2009) and on photography in East Asia for Photo Researcher (April 2011). His articles have appeared in Visual Resources, Early Popular Visual Culture,the La Trobe Journal, and History of Photography, and in exhibition catalogues for the National Gallery of Victoria and the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. He has been awarded fellowships by the Austrian government, the Australian Academy of the Humanities, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and the Research School of the Humanities and the Arts at the Australian National University. With the support of an Arts and Humanities Research Council Early Career Fellowship, he is currently completing a monograph provisionally titled A Career of Japan: Baron Raimund von Stillfried and the Business of Yokohama Photography.

Yi Gu is assistant professor at the University of Toronto. Her research focuses on modern Chinese art and photography history. She has presented on such topics as the Chinese nomenclature of photography, imperial patronage of photography, and landscape photography and changing visuality. She organized the panel “Photographic Practices, Visual Transgression, and National Identity in Meiji Japan and Early Republican China” at the Association for Asian Studies annual conference in 2009. She is currently working on a book manuscript, Scientising Vision in China: Photography, Outdoor Sketching, and the Reinvention of Landscape Perception.

Christine Kim, assistant professor at Georgetown University, is a historian of Korea, specializing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Her broad research interests include the interplay between culture and politics in the formation of national identity. She is presently completing a book on the significance of the Chosŏn monarchy (1392–1910) in twentieth-century Korea and commencing work on a new project examining the history of national treasures.

Yuhang Li will conduct postdoctoral research at Yale during the 2011–12 academic year. She received her PhD from the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago in June 2011; her dissertation was titled “Gendered Materialization: An Investigation of Late Imperial Chinese Women’s Artistic and Literary Reproductions of Guanyin.” Before she joined the University of Chicago, she graduated with a BA from the Art History Department in the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, China, and then received an MA from the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures in the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She also worked at the Beijing Art Museum and the Field Museum of Natural History. She is currently cocurator, with Judith Zeitlin, of an exhibition of opera in the Chinese visual arts.

Hyung Il Pai received her PhD from Harvard University, majoring in anthropology and East Asian archaeology. She is an associate professor at the East Asian Department of Language and Cultural Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where she has taught courses on Korean archaeology, history, anthropology, popular culture, and literature, and East Asian traditions and tourism. She is the author of Constructing Korean Origins: A Critical Review of Archaeology, Historiography and Racial Myth (Harvard University Asia Center, 2000) and coeditor of Nationalism and the Construction of Korean Identity (University of California, Berkeley, East Asia Center Monograph Series, 1998). She has also published in a wide range of international journals and contributed book chapters on diverse topics including Korean state formation, culture contact and change, archaeological heritage management, museum studies, photography, and cultural tourism in Korea and Japan. Her latest book, Re-inventing Antiquity and Patrimony: The Politics of Heritage Management in Korea and Japan, is forthcoming from the University of Washington Press (expected in 2012).

Maurizio Peleggi is associate professor of history at the National University of Singapore. He is the author of Thailand, the Worldly Kingdom (London: Reaktion, 2007), Lords of Things: The Fashioning of the Siamese Monarchy’s Modern Image (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2002), The Politics of Ruins and the Business of Nostalgia (Bangkok: White Lotus, 2002), and several journal articles and chapters in edited volumes on Thailand’s visual and material culture. In addition, he is the coeditor (with John Clark and T. K. Sabapathy) of Eye of the Beholder: Reception, Audience and Practice of Modern Asian Art (Sydney: Wild Peony Press, 2006).

Ying-chen Peng is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles. She studies the art history of late imperial China, particularly the process whereby popular culture merged into court art and how gender difference was reflected in visual culture. Her dissertation, “This Imperial Body: The Cultural Enterprise of Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908),” looks at the empress dowager’s patronage and activities that increased the visibility of popular culture and feminine expressions in late Qing court art.

Claire Roberts is a historian of Chinese art and a curator. She is a research fellow at the College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University (ANU). She was a coordinate research scholar at the Harvard-Yenching Institute, Harvard University, in 2011; research fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard from 2009–2010; and senior curator of Asian arts at the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, from 1988–2010. Roberts studied at the Beijing Foreign Languages Institute from 1978–79 and the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing, from 1979–81. She has an MA from the University of Melbourne. Her PhD, completed at ANU, focused on the work of modern Chinese brush-and-ink painter Huang Binhong (1865–1955). Roberts has published widely on Asian art and curated numerous exhibitions. Her most recent publications are Friendship in Art: Fou Lei and Huang Binhong (2010), Other Histories: Guan Wei’s Fable for a Contemporary World (2008), and The Great Wall of China (2006). Her next book is forthcoming and titled Photography and China.

Mary Roberts is the John Schaeffer Associate Professor of British Art at the University of Sydney. She is the author of Intimate Outsiders: The Harem in Ottoman and Orientalist Art and Travel Literature (Duke, 2007) and has coedited four books: The Poetics and Politics of Place: Ottoman Istanbul and British Orientalism (Pera Museum and University of Washington Press, 2011), Edges of Empire: Orientalism and Visual Culture (Blackwells, 2005), Orientalism’s Interlocutors: Painting, Architecture, Photography (Duke, 2002), and Refracting Vision: Essays on the Writings of Michael Fried (Power Publications, 2000). She has received grants from the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, the Australian Academy of the Humanities, and the Australian Research Council, and has been awarded residential fellowships at the Yale Center for British Art (2008), the Getty Research Institute (2008–2009), the Clark Art Institute and Oakley Center for the Humanities (2009–2010), and the Alice Kaplan Institute for the Humanities at Northwestern University (2011–12). She is currently writing a book on the artistic exchanges between Ottoman and Orientalist artists in nineteenth-century Istanbul.

Roberta Wue is an assistant professor of art history at the University of California, Irvine. Her research investigates the visual culture of late Qing China, with a particular interest in the relationships between image makers, images, and their various audiences. She has published on painting, photography, and advertising in nineteenth-century China. Her current book project focuses on the nineteenth-century Shanghai art world and its interactions with a new urban audience through such channels as painting, illustrated books, portraiture, and the mass media. Her work on photography in China includes the 1997 Asia Society exhibition Picturing Hong Kong: Photography 1855–1910 and an essay on the nineteenth-century Chinese portrait sitter in Body and Face in Chinese Visual Culture (Cambridge, 2005).

Session I: Self-creation and Personal Agency

Yi Gu, University of Toronto

Prince Chun through the Lens: Negotiating Photographic Medium in Royal Image

Prince Chun Yihuan (1840–1891) belonged to the innermost circle of the Manchu imperial clan. He was the seventh son of the Daoguang Emperor (1782–1850), brother-in-law of the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908), father of the Guangxu Emperor (1871–1908), and grandfather of Puyi, the Xuantong Emperor (1906–1967). Encumbered by his complicated relationship with the Empress Dowager, whose histrionic favoritism toward him was matched only by her incurable distrust, Prince Chun has often been portrayed in historical writings as an overcautious figure, restrained from bold action or self-expression. Yet he avidly embraced photography, collecting, exchanging, organizing, and staging photographic portraits. This paper explores how Prince Chun’s engagement with photography challenges the passive role history has assigned him. It also more broadly examines how royal patrons adopted photographic portraiture to mediate delicate political relations and to construct self-identities as a response to mounting demands for modernity.

Ying-chen Peng, University of California, Los Angeles

Lingering between Tradition and Innovation: Photographic Portraits of Empress Dowager Cixi

(1835–1908)

As the de facto ruler of the Qing dynasty (1636–1912) during its last five decades, Empress Dowager Cixi witnessed the modernization of how sovereignty was represented in China. To adapt to international diplomatic conventions, in the late 1890s Cixi began to integrate Western depictions of royalty with traditional Chinese expressions of power. In this process, the newly introduced medium of photography played a crucial role. Cixi commissioned many photographic portraits from around 1903 to 1904. She bestowed some of them to foreign rulers and, on occasion, to her own high officials.

This paper argues that beyond their practical functions, Cixi’s photographic portraits are images situated between convention and innovation, and that they must be given a new context. She commissioned these works within the tradition of Chinese imperial portraiture, a genre whose images were rarely displayed to the general public—yet she used them to create a public persona. By examining her photographic portraits and earlier Chinese imperial portraits, Peng reconstructs the process of such image-making and pinpoints the subtle lines between Cixi’s public and private images.

Ali Behdad, University of California, Los Angeles

Portrait Photographs: Constructions of Masculinity; Representations of Power

The portrait, as John Tagg reminds us, is “both the description of an individual and the inscription of social identity,” as well as “a commodity, a luxury, an adornment, ownership of which itself confers status” (The Burden of Representation, 37). This paper considers the plural functions of royal portrait photography in Iran during the Qajar dynasty: as a means of self-expression, as an inscription of royal power, and as a status symbol. It focuses on a series of images of Nasir al-Din Shah (1831–1896). Whether they were self-portraits or taken by a professional, these photographs conveyed the opulence, grandeur, and patriarchal nature of Qajar monarchical power. Such portraits, often depicting the shah in his royal gown and with a stern expression suggestive of his despotic authority, were given to local officials and various dignitaries as royal gifts and as signifiers of status.

Session II: Personal Manifestations of Nationhood

Luke Gartlan, University of St. Andrews

The Reverent and the Everyday: Presenting Imperial Photographic Portraits in Meiji Japan

This paper examines the display and circulation of the imperial photographic portraits of Emperor Meiji and Empress Haruko. Throughout the late nineteenth century, public policy and governance of these official photographic portraits shifted between strict censorship of their commercial sale and widespread distribution and public display. Regular press reports of the period emphasized the portraits’ official display and, in turn, the periodic police crackdowns on their unsanctioned distribution. The imperial photographs served many roles, including as public spectacles in government buildings, parks, and other sanctioned spaces; as private icons of devotion; as commodities of clandestine trade; as venerated icons in schools; and as objects of diplomatic exchange. Gartlan argues that these modes of display and distribution were critical to imperial portraiture’s political significance. Along with the emperor’s public appearances, the imperial photographs served to galvanize a range of social spaces for the education of his subjects—vital to the formation of the modern nation-state.

Hyung Il Pai, University of California, Santa Barbara

Romancing the Ruins of Imperial Antiquity: Travel Myths, Memories, and the Marketing of Heritage

Destinations in Korea

Photographs of decaying ruins have captured the imagination of explorers, artists, writers, and travelers for more than two centuries. This study introduces the earliest body of travel photography depicting Korea’s most famous landmarks, featured in archaeological reports, museum catalogues, photo albums, postcards, posters, and travel guides. Regardless of the medium, archaeologists, art historians, politicians, and commercial photographers have focused on promoting the “picturesque” beauty of the oldest royal tombs, Buddhist art, palaces, shrines, fortresses, and temples. By analyzing a number of the most widely circulated stock images of landscaped monuments—which have served as favorite backdrops for framing portraits of royal family members, visiting dignitaries, courtesans, peasants, and children—this paper demonstrates how such highly exoticized, romanticized, and anachronistic visions of “authentic” Korea continue to impact self-representations of the nation and its people. It demonstrates how images of royal patronage, native types, and celebrities posed among the ruins of vanquished “Other” have served not only as tools of political legitimization, diplomacy, education, and assimilation, but also as a powerful marketing strategy for the tourist industry to advertise “must-see” destinations to a world audience.

Roberta Wue, University of California, Irvine

The Mandarin at Home and Abroad: Picturing Li Hongzhang (1823–1901)

The limited public representation of rulers and political figures in imperial China began to change only at the very end of the dynastic period. Today, it raises the intriguing question of how and why public figures are represented in the modern era. The celebrated late Qing photographs of Cixi (1835–1908), fantastical and self-directed, acknowledge the possibilities of new technologies and new expectations. These quasi-private portraits of the Empress Dowager operated in interesting contrast to contemporary images generated in the modern media of Li Hongzhang, the eminent general, statesman, diplomat, pragmatist, and reformer. Li’s status as a prominent and controversial Chinese public figure is pictorially encountered in a surprisingly wide range of illustrations, prints, caricatures, and photographs, published in books, journals, and newspapers at home and abroad. The diversity of these images and the ways in which he was depicted reflect the spectrum of viewpoints that could either castigate or celebrate Li as a representative of China and the Chinese. Among them are a number of photographic portraits, some made directly under Li’s aegis, which suggest he crafted a sober, masculine public image for use as diplomatic gifts and as event markers. These pictures address the possibilities and uses of late Qing representations of the Chinese public figure.

Session III: Photographs and other media

John Clark, University of Sydney

Presenting the Self: Pictorial and Photographic Discourses in Nineteenth-century Dutch Indies, Siam, and Japan

In nineteenth-century Asia, photographic portraits did not exist as a separate visual discourse from portraiture. They frequently were introduced as part of a mastery of new kinds of representation, which penetrated aristocratic society first but soon spread to the rich and often the professional middle classes. Photographic portraits were not just indexical links to the subject but also images that presented the sitter in a symbolic space, often governed by both political intentions and institutional learning about new representational modes.

How did portraiture—created in oil and sometimes in modified forms of pre-modern customary media—affect the practice and subjects of photographic representation? How was it used by the state to reformulate and solidify images of the symbolic ruler in different contexts? What types of portrait were suitable to replicate for the elites and then for the general population in new educational systems? Did these images change when they were mass-produced in new forms of mass media? This paper approaches these questions via comparative analysis of the work of artists, photographers, and printmakers in the Dutch Indies (later Indonesia), Siam (later Thailand), and Japan.

Deepali Dewan, Royal Ontario Museum, University of Toronto

Embellished Reality: Paint and Photography in Studio Portraiture from India

Indian painted photographs are a unique aspect of photographic history and a distinctive genre of Indian visual culture. Dominated by portraiture, Indian painted photographs were not an attempt to enhance realism through the application of color. Rather, painting over the photograph was designed to enhance the status of the sitter and the affective power of the resulting image. This paper examines the production and use of Indian painted photographs. It also considers the insight they offer into the function of “realism” in South Asian art and the ontological status of the photograph in the Indian context.

Mary Roberts, University of Sydney

Ottoman Statecraft and the “Pencil of Nature”: Portrait Photography and Drawing at the Court of Sultan

Abdülaziz

The visual arts played a central role in Ottoman statecraft during the reign of Sultan Abdülaziz (1861–76), as the empire’s image was refashioned in tune with modernizing reform. Portraiture and history painting were used to create a modern image of the Ottoman leader, whose legitimacy premised on new historicization of the “glory days” of the empire. Abdülaziz was the first Ottoman sultan to harness photography to broadly disseminate his image. A painter himself, Abdülaziz was keenly aware of the potential uses of visual arts in the arena of international politics.

A folio of sixty-seven of the sultan’s sketches were presented to his court artist, the Polish painter Stanislaw Chlebowski, as working drawings for Ottoman battle paintings the sultan commissioned in the late 1860s and early 1870s. Chlebowski took the sketches back to Europe when he left Istanbul in 1876. They later were published alongside the sultan’s portrait in a series of journal articles in Poland (1909), London (1913), and Istanbul (1914). This paper investigates both the contemporary and posthumous legacies of the sketches and photographic portraits by examining the local and international impact of their joint circulation. The relationship between these two visual media provides unique insights into the function of Ottoman royal photographic portraiture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, both within the empire and abroad.

Session IV: Court and Religion

Maki Fukuoka, University of Michigan

Pictorializing the Emperor

One of the most prominent icons of modern Japan, the photographic portrait of the Meiji Emperor (goshin’ei) is intimately intertwined with the process of creating a national image during the Meiji Period. Indeed, prominent scholars of photography, such as Tagi Koji, Iizawa Kotaro, and Kinoshita Naoyuki, have explored this topic as a significant aspect of photographic history in Japan. The ceremonies mandated by the state for viewing goshin’ei and the calculated pattern of its distribution have also lead historians to situate the image within visual, colonial, and cultural contexts.

This paper examines the period before 1890, when the goshin’ei was first distributed nationally to governmental institutions. It compares the portrait to another cultural object known as “jingu taima,” a Shinto talisman distributed by the Meiji government that bore the name of the inner sanctum and red seal of the Ise Shrine. The period of experimentation with Shinto talismans curiously overlaps with the pivotal time that iconography of the Meiji Emperor was first established and distributed. Fukuoka articulates the tensions between mass-produced paper talismans and the photographically reproduced goshin’ei, as well as between the textual and pictorial and between religious and state sanctions.

Yuhang Li, Yale University

Mimicking Guanyin through the Lens: Cixi/Guanyin Photographs

The photographs of Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908) dressed up as Guanyin, the most popular female deity, have received considerable attention from scholars of Chinese cultural history in recent years. Scholars have begun to view these photographs as either an instrumental means in Cixi’s political campaign or as an example of the way she performs gender roles. In particular, some have stated that Cixi utilized Guanyin’s male and female forms to express her own inner masculinity or femininity. These approaches all have shed light on the complexity of Cixi’s Guanyin photographs; however, they have failed to scrutinize them in the context of Cixi’s general religious practice of the cult of Guanyin. This paper demonstrates that Cixi’s Guanyin photographs were a technique she adopted to extend and reframe her longtime practice of dressing up as the deity. Li situates Cixi’s practice in the larger historical context of imperial rulers embodying religious icons, and then points out the religious and historical substance of Cixi’s particular way of envisioning herself as a deity.

Claire Roberts, Australian National University

Chinese Imperial Portrait Photography: Reconciling Heaven and Earth

Chinese imperial portraits—representations of “heaven-endowed” physiognomy—were primarily created for ritual and commemorative purposes. Bound up with ideas related to cosmic power, they also embody the contradiction of the mortal quest for eternal life. How did the introduction of photography to China affect imperial portraiture? This paper examines photographs of Prince Chun Yihuan and the Empress Dowager Cixi, in particular those taken by Chinese photographers to commemorate birthdays. Roberts considers these images within the context of earlier Chinese imperial portraits and a legacy of curiosity with regard to representation and artistic expression.

Session V: Then and Now

Holly Edwards, Williams College

Timely Portraits: Afghan Women Then and Now

This paper spotlights two Afghan women who wielded significant transnational power by means of their widely disseminated portraits. The first is Queen Soraya. Collaborating in the 1920s with King Amanullah, she worked to alter the very terms of Afghan visual culture, particularly with regard to dress codes, gender roles, and new technologies like photography. Their modernizing campaign culminated in an unprecedented diplomatic tour, during which Soraya willingly posed unveiled for press photographers abroad. Portraits of her, conforming to those of socialites and debutantes, were widely disseminated via the Illustrated London News, generating British enthusiasm for her looks, her fashion sense, and her cosmopolitan poise. Her image worked to advance Afghan credibility in Europe even as it contributed to political instability at home.

Decades later, Sharbat Gula (commonly known as “the Afghan Girl”) gained similar celebrity, albeit without exercising any ambition or personal agency towards that end. Her green-eyed visage appeared on the cover of National Geographic (1985) just as American trendsetters were beginning to applaud “ethnic” appeal among high-fashion models. Serendipitously fashion-forward, Sharbat Gula captivated humanitarian fundraisers, becoming the poster child for Afghan refugees fleeing from civil war. This paper tracks these two Afghan women through cascading changes in local and global visual cultures, exploring powerful and fraught relationships between portraiture and visibility along the way.

Christine Kim, Georgetown University

Portraying Korea’s Colonial Monarchy:Images of Assimilation and Modernity

This paper examines the uses of photographs depicting the Korean royal family during the period of Japanese colonial rule (1910–45). Although annexation brought an end to Korea’s Chosŏn dynasty (1392–1910), Japan’s imperial project continued to utilize the symbolic cachet of the Korean throne. This colonization technique employed official and informal photographic portraits of members of the Korean royal household, depicting them as privileged subjects of the empire. These images, mass-produced and disseminated through a wide range of print media, offered glimpses of cosmopolitan glamour that packaged notions of assimilation and colonial modernity.

During the 1920s, an intense focus on “the last crown prince,” Prince Yŏng (1897–1964), promoted several themes: his professional life as an officer in the Japanese imperial army; his marriage to a scion of Japanese aristocracy and their subsequent family life; and his modern lifestyle, exemplified by new modes of consumption, recreation, and leisure—through which the colonial administration sought to reshape Koreans’ identity. In the subsequent decades, as Koreans were increasingly drawn into the Pacific War, a new theme of imperial loyalty and cultural assimilation was emphasized. Photographic images thus not only provide a way of understanding Korea’s colonial experience in the early twentieth century, but also illustrate a process in which colonial machinations gradually eroded the nationalist foundations of the throne.

Maurizio Peleggi, National University of Singapore

From Image to Icon: The Aesthetics and Politics of Thai Royal Portraiture

Ubiquitous display of the royals’ portraits is characteristic of public space in Thailand, one of the world’s few remaining monarchies, and mistreatment of these images notoriously can incur the charge of lèse majesté. Yet, because representing the royal self was considered taboo, the royal portraiture tradition was not prevalent in Thai visual culture until the mid-nineteenth century. At that time, domestic and international dissemination of the royal image through studio portraits, effigy on coins and banknotes, picture postcards, and book illustrations epitomized the palace’s modernizing drive. Starting with King Mongkut (r. 1851–68) and especially his successor, King Chulalongkorn (1868–1910), photographic portraits of Thai monarchs reveal their awareness of the importance of the ruler’s image in Western semiotics of power.

Thai royal portraiture thus underwent a peculiar change in status between the 1860s and 1960s. Increasing public familiarity with the sovereign’s image initially had a demotic effect: By the 1920s the Thai monarch was being caricatured in newspapers. This trend was reversed during the long reign of the incumbent monarch, Bhumibol Adulyadej (r. 1946–), which brought about the resacralization of the royal body and the iconization of portraits. This paper examines the photographic portraits of nineteenth-century Thai monarchs, and considers how they relate—formally, aesthetically, and ideologically—to the portraits that today hang on the walls of public premises and private homes alike.

Detail, The Empress Dowager Cixi; China, Qing dynasty, 1903-1904; Glass plate negative; SC-GR 254.

- Jump To...