November 10, 2007–April 13, 2008

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

Japanese Art

This selection of 109 Japanese Edo Period (1615-1868) paintings from the world renowned California-based collection of Joe and Etsuko Price, features screen, hanging scroll and fan formats. The Price Collection reflects the eclectic diversity of a remarkably creative span in Japan’s history of visual culture and is punctuated by some of the finest examples of the distinctive, hauntingly preternatural renderings of animal life by Ito Jakuchu (1716 -1800). The exhibition comes to the Sackler after completing a year-long tour of Japan.

The Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

The Etsuko and Joe Price collection is regarded as one of the world’s finest collections of paintings from Japan’s Edo period (1615-1868).

Ironically, within the more than two centuries of imposed national isolation, Japan’s traditional painting ateliers witnessed both continuity and unprecedented splintering, the emergence of individual talents, and degrees of eccentricity, variety, and creativity unmatched in previous centuries. The results are featured in the Price collection, which recently completed a highly acclaimed one-year tour of four major Japanese museums (July 2006-May 2007).

A variation of that exhibition is now presented at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery as Patterned Feathers, Piercing Eyes: Edo Masters from the Price Collection (November 10, 2007-April 13, 2008). The collection next will be on display at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (June 22-September 14, 2008), where the Prices have been instrumental in advancing the study and appreciation of Japanese art.

While the Price collection offers exceptional examples of the traditional and divergent styles of the Edo period, it was assembled with an eye to beauty rather than encyclopedic aims. Thus, it can be presented in multiple ways. We have chosen here to explore three major areas: the manifestations of legend, spirit, and myth in everyday life; the multiple meanings of landscape; and the preternatural presence of birds and beasts.

Although arbitrary, these divisions reveal an overall phenomenon: during the Edo period (1615-1868) in Japan, paintings began to incorporate a new sense of intimacy, even jocularity, with the divine and the revered past. In addition, birds and animals moved from having largely symbolic, heraldic roles to assuming more complex functions with highly individualized personalities. Images of the land reverberate with spirit and layers of meaning. In a sense, vertical hierarchies of the universe begin to tilt toward the horizontal.

The paintings of the Edo period announced that the alert eye could expect wholly new ways of encountering the world. By paying heed to the structure of nature, the structure of beauty would be revealed.

This exhibition has been made possible through the generosity of the Anne van Biema Endowment and Nikkei, Inc.

Rotations

To accommodate both the size of the collection and conservation requirements, the paintings in this exhibition will be rotated several times. Generally, screen displays will be changed three times and most hanging scrolls changed twice, with a few exceptions. There are 109 titled paintings in the exhibition. Because some “titles” are actually painting ensembles, the number of actual paintings runs to approximately 150. At any given time, approximately 50 works will be on display.

Most hanging scrolls will change during the period between January 14 and 25, 2008. Most screens will change between January 2 and 4 and, again, between February 18 and 22.

The Price Tower, Frank Lloyd Wright, and a Young Engineer

Harold Price (1888–1962), born in Washington, D.C., parlayed a one-man welding shop in Bartelsville, Oklahoma, into an international enterprise based on patented techniques for oil pipeline joinery. In 1952 his son, Joe D. Price, graduated from the University of Oklahoma with an engineering degree. Young Price was conscripted by his father to manage the construction of a new headquarters building. The architect Bruce Goff (1904–1982), a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright, had been a college professor of Price’s and recommended Wright for the job. The result was the Price Tower, Wright’s only skyscraper. Interaction with Wright on that project provided Joe Price with a foundational understanding about viewing the physical world. Attention to the underlying structures of the natural world would develop into a highly personalized aesthetic: a perfection of nature through an understanding of the elements. It was on a visit to New York City that Price accompanied Wright to an art dealer’s shop on Madison Avenue and purchased his first Japanese painting, a study of grapes by Itō Jakuchū (1716–1800).

Exhibition Highlights

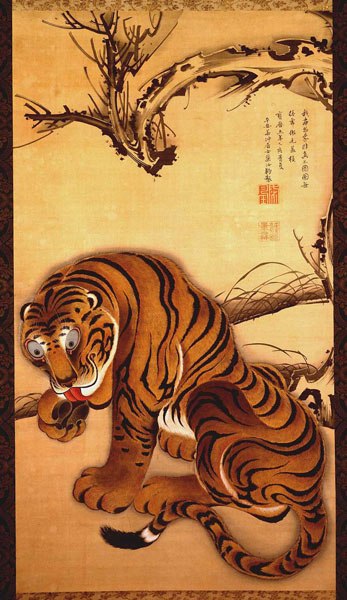

Tiger

Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800)

Japan, Edo period, Hōreki 5, 1755

Colors on silk

H x W (overall): 218 x 96 cm (85 13/16 x 37 13/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.44)

This painting was produced in the summer of 1755, when Jakuchu, at the age of forty, made the tortured decision to turn over the responsibilities of his family's wholesale greengrocery business to his younger brother and pursue the life of painting.

The choice of subject is deeply informative of the artist's state of mind. Jakuchu was thoroughly imbued in the practice of Zen Buddhism, and his most important works were commissions for major temples. In Zen thinking, the tiger represents a natural power that can be controlled through enlightenment seeking discipline. In the act of grooming, the tiger suggests a self-intention to move beyond a conflicted mental state and toward a focus of energy.

In the inscription Jakuchu writes, "When painting a material phenomenon, I would not paint it but from truth. Because there are no ferocious tigers in Japan, I have imitated the painting of [Chinese Southern Song artist] Mao Yi." That painting, in the collection of the Kyoto temple Shoden-ji, is now reckoned to be a Ming-dynasty work (1355-1644), but the passage speaks to Jakuchu's careful study and connoisseurship.

Image 1 of 23

Seven Cranes

Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800)

Japan, Edo period, 1716-1799

Colors on silk

H x W (overall): 210 x 71 cm (82 11/16 x 27 15/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.47)

This carefully composed ensemble of elegant birds was created by Jakuchu when he was in his early forties, around the time he became a full-time professional painter. Typical of his color renderings of the natural world, Jakuchu offers an arrangement that seems to replicate nature in its precision and detail but represents a thoroughly contrived pattern and structured flow of accent points. Cranes represent immortality and, when assembled in the fortuitous number seven, leave no doubt as to the celebratory intention of the painting. It has been

suggested that the multiple flowing directions of necks and legs roughly approximate the Chinese ideogram meaning good fortune.

Jakuchu was noted for his masterful control of thin layers of pigment. In this painting he adds a subtle sense of volume to areas of white by applying yellow pigment to strategic areas on the back of the silk. This technique was frequently used in full-color Buddhist paintings, but here Jakuchu successfully adapts it to more secular goals.

Image 2 of 23

Rooster, Hen and Hydrangeas

Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800)

Japan, Edo period, 1716-1799

Colors on silk

H x W (overall): 230 x 114 cm (90 9/16 x 44 7/8 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.49)

This work—like the painting of mandarin ducks in winter exhibited nearby in this gallery—is thought to be a prototype for a very similar work included in the thirty-three painting ensemble Jakuchu created between 1755 and 1765. The large group featured a triptych of Buddhist deities surrounded by thirty paintings of flora and fauna representing the natural world benevolently ruled over by the Buddha.

This rooster and hen set against a backdrop of blue hydrangeas and Chinese rocks reveals the precision and consummate design skill that Jakuchu had developed by his late thirties, working avocationally while still engaged in his family’s grocery business. This painting and the one of the mandarin ducks are thought to have been produced between 1754 and 1757 and provide important historical markers for the beginning of the artist’s mature and fully focused phase.

Image 3 of 23

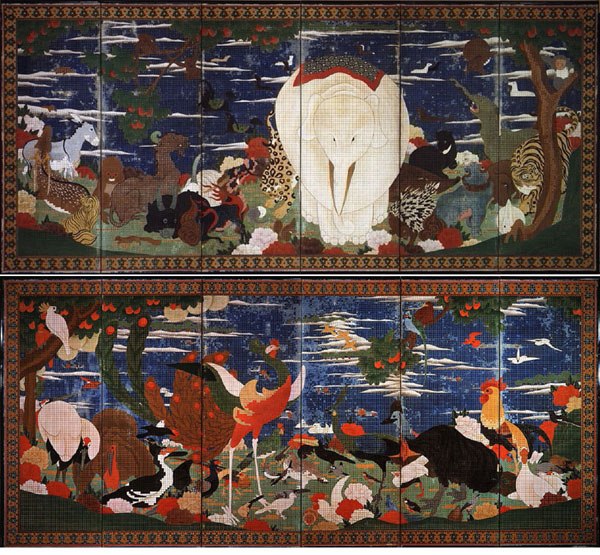

Birds, Animals, and Flowering Plants in Imaginary Scene

Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800)

Japan, Edo period, 1716-1799

Colors on paper

H x W (each): 168.7 x 374.4 cm (66 7/16 x 147 3/8 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.50)

With their distinctive “mosaic” format, these screens are among Jakuchu’s most unusual and inventive creations. The grid pattern is not an “overlay” on an already completed scene, but rather each tiny square, including the palette choices, is a carefully constructed composition. The interaction between the individual squares and the total image is the special achievement of these paintings.

The subject of a menagerie of real and fanciful creatures existing in harmony under the benevolent eye of the Buddha is the theme of Jakuchu’s most important commission—the thirty-three paintings comprising “the colorful world of living beings” (Doshokusai-e)—created for the Kyoto temple of Shokokuji between 1755 and 1765. A religious theme was probably intended for these screens. Most scholars regard a similar set of screens in a Japanese museum collection to be the prototype for the more finished pair on display here.

The grid pattern is thought to have some connection to techniques used in textile design. Major textile producers in Kyoto were also affiliated with Shokokuji, and a commission to produce a Buddhist iconographic subject with references to their craft seems likely.

Image 4 of 23

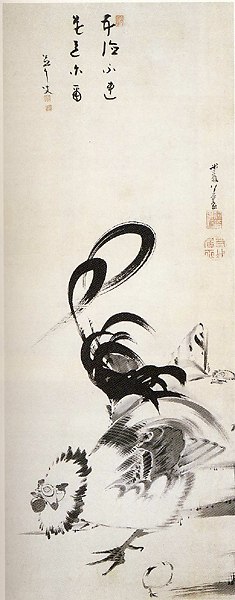

Rooster Family

Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800)

Japan, Edo period, Kansei 8, 1796

Ink on paper

H x W (overall): 206 x 63 cm (81 1/8 x 24 13/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.53)

This vigorously conceived work suggests a rooster in a defensive posture with ruffled collar and swirling tail feathers. Rooster, hen, and chick glare in the same direction at some threat not visible to the viewer.

Jakuchu painted this dynamic work when he was already in his eighties and only two years before his death. The inscription in the upper left was written by Jiun (1716–1804), a resident of Osaka and a high-ranking monk of the Tendai Buddhist sect. The inscription references the Five Virtues associated with the rooster: learning, martial spirit, bravery, benevolence, and faith. The rooster also announced the end of darkness and, with it, the dispersal of uncertainty and evil spirits. Buddhism absorbed these meanings and also saw the rooster as symbolic of the seeker’s intense devotion to enlightenment and its crowing at dawn as the announcement of transformative insight.

Image 5 of 23

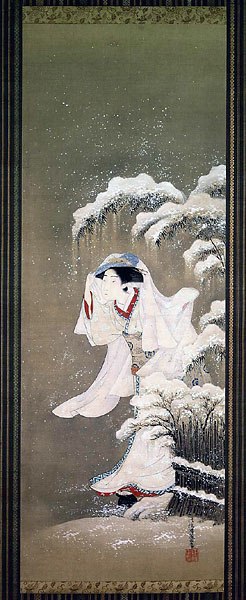

Courtesan in Snow

Isoda Koryusai (Japanese, 1735-1790)

Japan, Edo period, 1700-1799

Colors on silk

H x W (overall): 180 x 47 cm (70 7/8 x 18 1/2 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.70)

The delicate beauty depicted here ranks as one of Koryusai's most exquisitely conceived paintings. Known for his skill in rendering women in atmospheric contexts, Kyorusai carefully blends tonalities from white to gray with brilliant red accents to create a willowy creature who seems to be evolving out of the dense, wet air of a heavy snowfall. The effect achieves a balance between the subject's delicacy and the weight of the atmosphere.

In 1760, producers adapted a Noh drama dance routine titled The Heron Maiden (Sagi musume) for the more popular Kabuki stage. The protagonist was associated with snowfall and possibly inspired an interest in images of courtesans in snow. Koryusai designed woodblock prints precisely referencing the play, but there is only a generalized connection between this painting and the theme.

Koryusai is thought to have been associated with the painter and print designer Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770), credited with introducing full-polychrome woodblock prints into commercial prominence in the 1760s.

Image 6 of 23

House of Pleasure

Kawanabe Kyosai (Japanese, 1831-1889)

Japan, Meiji era, 1831-1889

H x W (overall): 156 x 89 cm (61 7/16 x 35 1/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.80)

While Daruma is the singular subject of the painting on the left, here Kyosai has downgraded the image of the patriarch to a decorative but visually unavoidable element in a brothel's party room. There, his visage observes the raucous interaction in a "teahouse" of the Yoshiwara pleasure district in Edo.

Kyosai places his signature and seal--in this case, "the lay priest Kyosai"--on the "painting-within-the-painting," the single-panel screen bearing the Daruma's image. In effect, the artist claims authorship of the patriarch's image but not of the collateral debauchery. Kyosai hardly had the reputation of a prim teetotaler, but he was openly critical of profligate government officials.

Image 7 of 23

The Thirty-six Immortal Poets

Sakai Hoitsu (1761-1828)

Japan, Edo period, 1800-1828

Colors with gold on paper

H x W: 164.5 x 180 cm (64 3/4 x 70 7/8 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.92)

In the beginning of the eleventh century, Japanese imperial anthologists began to codify the works of great poets of the past and established a canonical group of thirty-six immortals. The group included five women and two Buddhist monks whose periods of activity ranged in date from the seventh into the eleventh century. By the thirteenth century paintings were featuring imagined portraits of these poets juxtaposed with representative verse. Later, illustrated poetry competitions became a popular painting subject. Light-hearted and comedic representations of the great poets at leisure were a staple in the wider Edo context of parodying the past.

This painting is based on a very similar image created by Ogata Korin (1658-1716), an artist whose stylistic direction Hoitsu sought to revive and continue. As in Korin's model, here, too, only thirty-five poets are seen; in deference to her imperial status, the thirty-sixth, Saigo no Nyogo, is presumed to be behind the curtain at the upper right.

Image 8 of 23

The Sano Crossing

Sakai Hoitsu (1761-1828)

Japan, Edo period, 1800-1828

Colors with gold on paper

H x W: 150.2 x 154 cm (59 1/8 x 60 5/8 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.93)

The crossing at the Sano ford was a subject dear to the Edo- period revivalists of ancient courtly themes. This lineage of painters extended from the late sixteenth through the late nineteenth century and has been named, after the fact, the Rimpa school. Foremost in this stylistic tradition were Tawaraya Sotatsu, Ogata Korin, Sakai Hoitsu, and Suzuki Kiitsu. Extant examples of treatments of this subject span more than two centuries and have essentially the same composition: a mounted courtier and attendants on foot traverse a vaguely indicated snow-blown and windy passage.

Referenced in ancient poems, the Sano crossing was a pontoon bridge traversing Karasugawa River in the mountains northeast of the capital, Kyoto. During the Heian period (794-1185), the dread associated with administrative assignments in distant provinces was immortalized in poetry that conveyed the pain of separation from loved ones and the vital cultural life of Kyoto.

Image 9 of 23

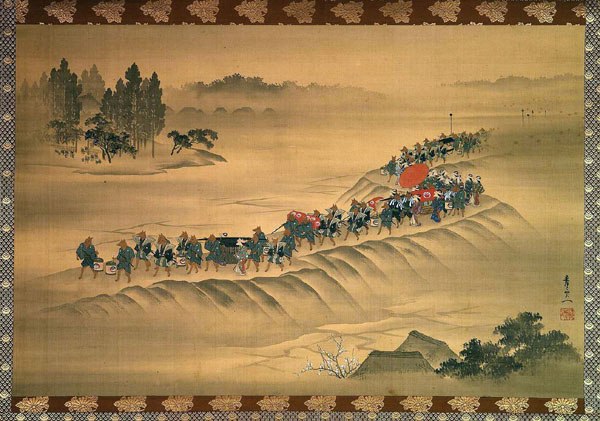

Fox’s Bridal Procession

Suzuki Kiitsu (1796-1858)

Japan, Edo period, 1800-1858

Colors on silk

H x W (overall-estimate): 180 x 110 cm (70 7/8 x 43 5/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.97)

In Japan, as in many other cultures, the fox has long been associated with trickery and deception. Many tales and legends credit the fox with the ability to morph into the form of a seductive woman. The phrase "a fox's bridal procession" refers to two distinct forms of deceptive visual phenomena: the sparkling atmosphere perceived when rain falls while the sun is shining, and a nighttime occurrence of seemingly inexplicable specks of light flashing in the darkness.

Kiitsu takes the phrase literally and produces an image of a rural bridal procession in which foxes assume the formal garb of the wedding retinue. The lantern-bearing procession moves at dusk toward a shrine at the upper left, where the groom's family, rendered in silhouette, awaits the bride. According to Japanese lore, it is at dusk-the quintessential transitional time-rather than in the darkness when one encounters figures of the spirit world. Kiitsu places the viewer in the role of the unsuspecting traveler who observes the transformation of an otherwise mundane rural landscape.

Image 10 of 23

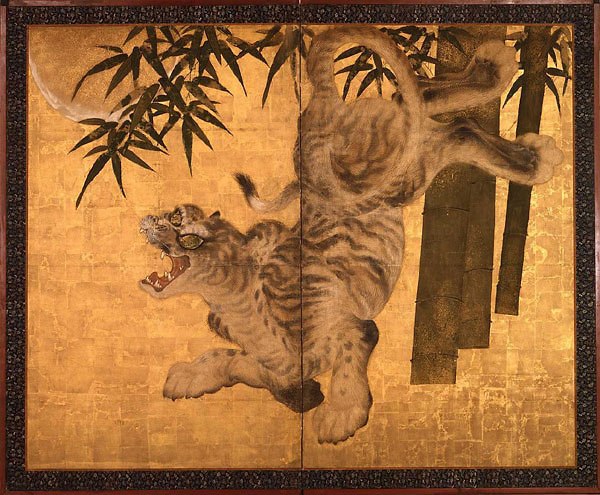

Tiger and Bamboo

Japan, Edo period, 1600-1699

Colors with gold on paper

H x W: 132.5 x 164 cm (52 3/16 x 64 9/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.7)

During the Muromachi period (1333–1573) images of tigers were integrated into the décor and iconography of both the residences of Japanese warriors and monasteries. To the former they symbolized martial ferocity, and to the latter they made a subtle reference to treacherous forces of the spirit, which demanded vigilant reckoning.

The painting reflects the style of the dominant Kano school of painters that served the shogun, daimyo clients, and important temples. But this animated, leaping tiger, perhaps a fragment from a larger screen or a sliding-door painting, has no apparent Japanese precedent. It heralds the gradual transition from emblem to personalized form seen in the paintings of animal life during the course of the Edo period.

Image 11 of 23

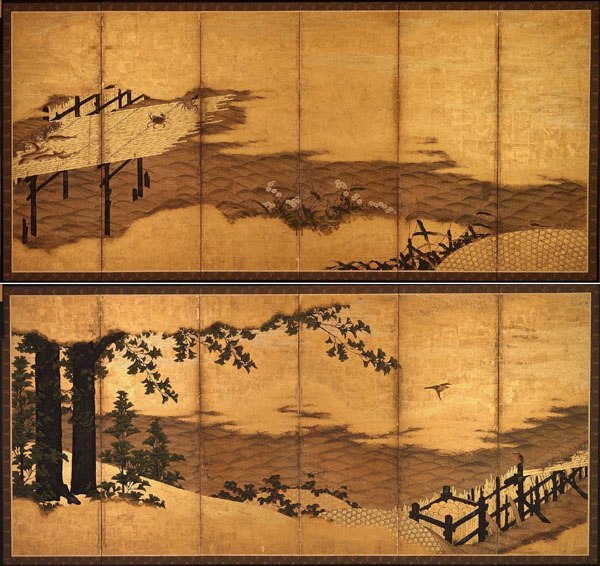

Fish Weir

Japan, Edo period, 1600-1899

Colors with gold on paper

H x W (each): 162.5 x 359 cm (64 x 141 5/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.10)

The subject of fishing weirs or traps set in a river is rare if not unique. This painting contrasts a skillfully assembled group of pattern types-the rendering of flowing water, the trap's bamboo structure, the honeycomb-shape of the baskets-with the less uniform repetitions of ginkgo, ivy, and bamboo leaves. Kingfishers, trout (ayu), a few crabs, and a wagtail are the active natural elements. Through this arrangement the painter establishes rhythmic flow interrupted with grace notes. The background stillness of early autumn is punctuated by occasional sounds of fish and feather.

As they try to jump the structure, the fish land on the bamboo platform, from which they are then quickly plucked by hand. Amid various forms of human invention, the absence of human figures is noteworthy.

Image 12 of 23

Tiger

Genki (1747-1797)

Japan, Edo period, 1747-1797

Color on silk

H x W (image): 63.1 x 85.8 cm (24 13/16 x 33 3/4 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.15)

The richly detailed rendering of fur-hair by hair-and the characteristic dark-banded striations give an effective sense of the deep pile of this creature's coat. Genki approaches a subject dear to his master, Maruyama Okyo (1735-1795), but presents the big cat using his own

unique pose.

On view in this gallery is another painting of a tiger in a similar pose. That work is by Ito Jakuchu, an older contemporary of Genki and most certainly known to him as one of Kyoto's most distinguished painters. The inscription on Jakuchu's painting cites the work of a Southern Song painter found in a Kyoto temple as his source. Later research has revealed the painting to be from the Ming dynasty (1355-1644).

Image 13 of 23

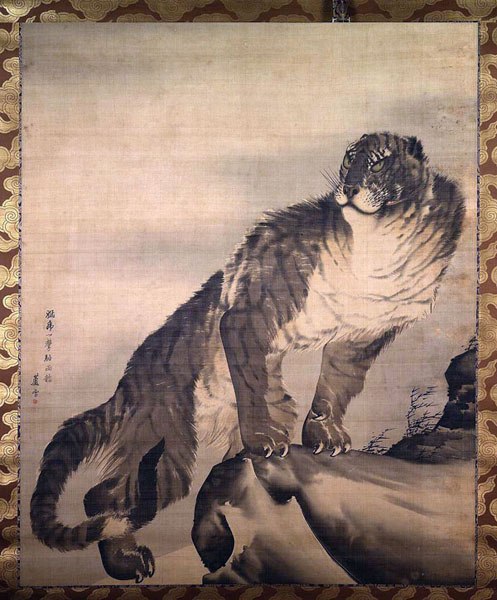

Tiger

Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799)

Japan, Edo period, 1754-1799

Ink and light colors on silk

H x W (image): 163.5 x 131 cm (64 3/8 x 51 9/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.16)

Through a masterful blend of ink-wash and brush techniques, Rosetsu presents the imposing volumetric presence of a tiger. Against a darkened sky, a few wind-blown sprigs on the ground and the ruffled fur on the tiger's shoulder suggest an impending atmospheric shift that mirrors the animal's potential to unleash great force.

An inscription by the artist near the signature can be translated as: "The roar of the tiger stops two dragons." With a long history in China as symbols of primal cosmic forces, both tigers and dragons entered the iconography of Zen Buddhism in several ways. They were depicted as tamed at the feet of the Buddha's disciples or as more active and threatening forms, as in this painting. Both creatures represented natural forces and human desire, sometimes calm but always ready to erupt, thus requiring the constant vigilance of Zen practitioners.

Image 14 of 23

Rooster in Rain

Kishi Ganku (1749-1838)

Japan, Edo period, 1749-1799

Colors on silk

H x W (image): 119.6 x 36.8 cm (47 1/16 x 14 1/2 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.20)

The rooster standing resolute against the slashing downpour is a novel approach to a popular subject, though expected from a painter known for slightly twisted or sardonic interpretations of clichéd topics.

Ganku came from Kanawaza on the Japan Sea, north of Kyoto, and settled in the capital in 1780. He launched a very successful career, but his shameless self-promotion and craving for honorary titles did not endear him to his peers.

This painting bears seals and a signature that date it to the late 1780s when the artist was in his late thirties. Ganku was well versed in a range of painting styles and here exhibits mastery of the so-called Nagasaki style, a Japanese adaptation of Ming-style full-color painting with particular interest in bird and flower subjects. The painter So Shiseki (1715–1786) was the main exponent of this style. Ganku’s other works of the period make direct inscribed references to his homage to Shiseki. This painting could well be mistaken for a work by that master.

Image 15 of 23

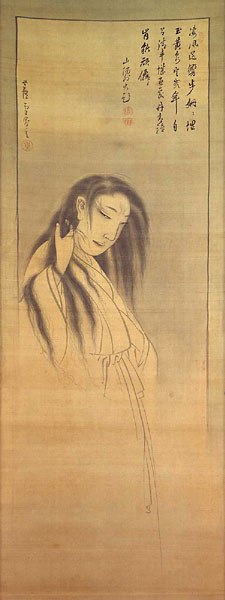

Ghost

Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799)

Japan, Edo period, 1754-1799

Ink and light colors on silk

H x W (image): 162 x 40 cm (63 3/4 x 15 3/4 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.22)

Likely in response to a heightened popular interest in the subject during the second half of the eighteenth century, images of ghosts proliferated. Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795), Rosetsu's mentor, is generally credited with originating singular "portraits" of ghosts who floated legless in the thick night atmosphere. The writer Ueda Akinari (1734-1809) was the most proficient exponent of supernatural tales and moved within the circle of Okyo and his disciples.

The rendering of this ghost is based on the Okyo prototype. The female ghost brushes back scraggly hair with her right hand and turns her head with a reproachful gaze to the viewer.

A verse by the poet Rai San'yo (1781-1842) is inscribed at the upper right.

Image 16 of 23

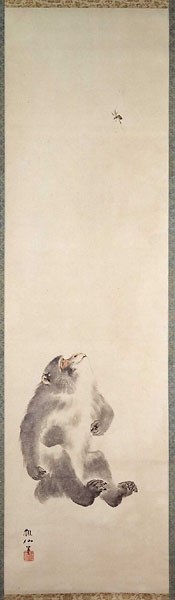

Monkey and Wasp

Mori Sosen (1747 - 1821)

Japan, Edo period, 1800-1821

Ink and light colors on paper

H x W (overall): 188 x 37 cm (74 x 14 9/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.27)

Best known for his paintings of monkeys and deer, Sosen here produces an image with auspicious connotations. The word for wasp (hachi) and the word for fief or domain (hochi) are close in sound. In addition, the pronunciation of an ideogram for monkey is ko, the same sound as the term for a lord. The combination of these complex associations is intended to represent a person about to be granted lordship of a domain or, more broadly, a way of announcing significant advancement.

Sosen renders the monkey as being intently focused on the insect, with his left arm cocked as though he is about to strike--but what is within his grasp might also sting.

Image 17 of 23

Monkey Peering over a Cliff

Watanabe Nangaku (1767-1813)

Japan, Edo period, 1767-1818

Hanging scroll

H x W (overall): 216 x 71 cm (85 1/16 x 27 15/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.28)

Variations of this pose are seen in works by Rosetsu, who like Nangaku was a follower of Maruyama Okyo (1735- 1795). There were ample opportunities in the mountains surrounding Kyoto to observe wild monkeys, and while there is a delightful sense of caricature to this creature, Nangaku may be representing something he had seen in a forest. This work also might refer to the ancient Zen cautionary tale of the monkey who grasped at the moon's reflection in the water--death, real or spiritual, can result from reaching for an illusion.

Image 18 of 23

Tiger

Kameoka Kirei (1770-1835)

Japan, Edo period, 1770-1835

Colors on silk

H x W (overall): 199 x 61 cm (78 3/8 x 24 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.36)

Kirei's tiger, a startling contrast to the delicate flowers depicted in the painting on the left, nevertheless employs a strikingly similar compositional format. The foreshortened, curving body aligned on a vertical axis presents feline movement and a tensile strength barely contained within the framework of the painting's borders.

Tiger pelts were occasionally available for painters to examine, but the live creature was not indigenous to Japan. The paintings that resulted were imaginative acts that blended knowledge of domestic feline anatomy with fragmentary evidence of the more ferocious beast. Tigers were a favored subject of Kirei's master, Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795).

The poetic inscription in the upper left of the painting is signed by Gazan, about whom nothing is known; the name may be that of a Zen monk.

Image 19 of 23

Tiger

Katayama Yokoku (1760 - 1801)

Japan, Edo period, 1760-1799

Ink and light colors on silk

H x W (overall): 197 x 58 cm (77 9/16 x 22 13/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.38)

Yokoku creates a formidable presence through a deft combination of palette choice and composition. Fur rendered roughly in shades of ink forms a foreboding setting for eyes, mouth, and ears, all purposefully accented in bold color. In addition, the only partially visible body hints at a force yet to be unleashed.

The eyes and retracted claws suggest an exposure to Korean painting models. Most Japanese painters were familiar with tigers only from painting models from the Asian continent—Manchuria, Korea, China, and Siberia—or from looking at hides. Those unfamiliar with either

models or the actual beasts often rendered them striding with claws extended—a dramatic but physically inaccurate image.

Image 20 of 23

Tiger

Kokuho

Japan, Edo period, 1700-1799

Ink on paper

H x W (overall): 204 x 118 cm (80 5/16 x 46 7/16 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.39)

Very little is known about Kokuho. He seems to have worked in the Nagasaki area, the center for international exchange in an otherwise isolated Japan. Evidence indicates that Kokuho produced underdrawings and sketches that were transformed into woodblock prints. In addition to this tiger painting, a pair of his screen paintings featuring scenes of Dutch and Chinese life is also known. The combined but admittedly limited evidence suggests an interest in exotica. His rendering of the tiger bears a strong schematic resemblance to concepts popular in Korea, but the details of the fur and the nuances of wash that shade the entire painting reflect techniques more common in Japan.

Image 21 of 23

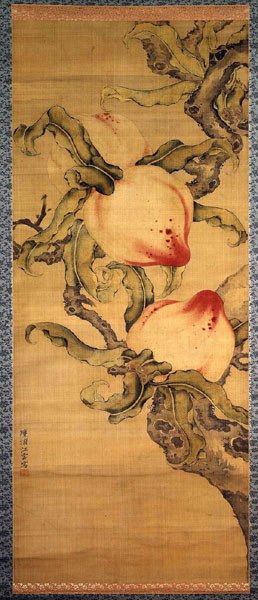

Peaches of Immortality

Iwai Koun

Japan, Edo period, 1700-1799

Colors on silk

H x W (overall): 202 x 73 cm (79 1/2 x 28 3/4 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.40)

The three peaches seen here symbolize the peach tree of Xiwangmu, the Immortal Mother of the West in Chinese mythology. The tree produces fruit once every three thousand years, and anyone fortunate enough to eat one of the peaches is granted eternal life. This painting subject is auspicious and presumably was commissioned for a celebratory occasion.

In the seventeenth century Chinese immigrant painters worked in the port city of Nagasaki and produced images of heightened realism in a full, lush polychromy. A latter-day exponent of the style, Koun produced a startlingly voluptuous painting that explores the erotic potential of the traditional symbolism.

Image 22 of 23

Grapevines

Ito Jakuchu (1716-1800)

Japan, Edo period, 1716-1799

Ink on paper

H x W (overall): 208 x 47 cm (81 7/8 x 18 1/2 in)

Etsuko and Joe Price Collection

(ELS2007.4.42)

The subject of grapes was one of the traditional formats used by East Asian painters to demonstrate skill in the manipulation of ink shapes and tonalities. The bold interaction of vertical and horizontal forms as well as the kinetic energy achieved by a partial revelation of forms reveal a hand well on its way to distinctive maturity.

This painting is signed by Jakuchu with the comparatively early sobriquet of "Keiwa." It has particular importance as it was the first Japanese painting purchased by Joe Price. He bought it on a day spent in New York with architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1953. Jakuchu's work, here and in other paintings acquired later, would become the critical criterion of the Price collection.

Image 23 of 23

Seven Cranes; Itō Jakuchū (1716-1800); Edo period, 18th century; Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk; 108.8 x 49.4 cm

- Jump To...