June 25–September 11, 2005

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

Ancient Near Eastern Art

For over a thousand years, from around 800 B.C.E. to 600 C.E., the kingdoms of Qataban, Saba (biblical Sheba), and Himyar grew fabulously wealthy from their control over the caravan routes of the southern Arabian peninsula and, in particular, from the international trade in frankincense and myrrh. Excavations at the capitals of these ancient kingdoms have yielded spectacular examples of architecture, distinctive stone funerary sculpture, elaborate inscriptions on stone, bronze, and wood, and sophisticated metalwork.

Drawn from the collections of the Republic of Yemen, the American Foundation for the Study of Man, the British Museum, and Dumbarton Oaks, this exhibition of approximately 200 objects explored the unique cultural traditions of these ancient kingdoms. It gave special emphasis to the rich artistic interaction that resulted from overland and maritime contacts linking the southern Arabian peninsula with the eastern Mediterranean, northeastern Africa, and south and southwest Asia.

For more than a thousand years, from around 800 BCE to 600 CE, the kingdoms of Qataban, Saba (biblical Sheba), and Himyar, in present-day Yemen, grew fabulously and famously wealthy. They derived their wealth from control over the caravan routes that crossed the southern Arabian Peninsula, and in particular from the international trade in frankincense and myrrh. Excavations at the capitals of these ancient kingdoms have uncovered monumental architecture, distinctive stone funerary sculpture, elaborately carved inscriptions, and sophisticated metalwork.

Admired for its fragrant and abundant foliage and luxuriant pastures, Yemen was central to the ancient “global economy” that once extended from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indian Ocean. It is no wonder that it was known to the Greeks and Romans as “Arabia the Blessed.”

This exhibition tells the story of these caravan kingdoms, whose fortunes rose and declined along with the demand for their resources, and explores the unique and little-known cultural traditions these kingdoms created.

A great desert, the Ramlat as-Sabatayn, occupies Yemen’s interior, and the caravan kingdoms established along this desert’s edges dominated the region during the first millennium BCE. Each of the four major valleys that flow from the tall surrounding mountains to the desert was occupied by a state—from west to east Saba, Qataban, Awsan, and Hadramawt. Their respective territories corresponded to the valley and its tributaries. In the early seventh century BCE, the kingdom of Saba extended its dominance over a wide area of southern Arabia and probably held this territory until the fourth century BCE, when Qataban took it over until the first century CE.

The kingdom of Saba, with its great capital at Marib, was organized around a common language (Sabaean), a shared cult of the god Almaqah and a pantheon of lesser deities, and centralized political institutions. The early Sabaean rulers held the title of mukarrib, “federator,” who made key decisions in consultation with other important figures represented in councils or assemblies.

Saba’s fabled prosperity—epitomized by the legendary Queen of Sheba—derived both from the incense trade and the agricultural resources created through intensive exploitation of the large Marib oasis. Sophisticated irrigation systems enabled the inhabitants of Marib and other desert oases to harness the floods that poured down mountain streambeds following seasonal rains, creating fertile fields for growing grains, food plants, and fruit orchards.

Around the first century BCE, political and economic interest shifted from Yemen’s inland desert to the sea and its nearby mountains. Maritime trade had superseded the old caravan routes. Only a state that controlled access to the ports along the peninsula’s southern coast could challenge the Roman Empire’s growing dominance of maritime trade from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean.

From its home in Yemen’s fertile southern highlands, the dynasty of Himyar gradually conquered the kingdoms of Qataban, Saba, and Hadramawt during the first centuries of the common era. During the fifth and early sixth centuries, the Himyarite kings ruled the entire southern Arabian Peninsula from their capital at Zafar and conducted a flourishing trade based primarily at their main port of Mouza (modern Mokka).

The Himyarite kings also contended with the growing presence of Abyssinia (Ethiopia), a Christian kingdom, which periodically gained control of southwestern Yemen. In the late fourth century CE, the Himyarite kings officially adopted a monotheistic religion, probably Judaism. Around 570 CE, the Sasanian dynasty that ruled the Near East and part of Central Asia took control of Yemen, and in 628 the last Sasanian governor of Yemen converted to Islam.

Himyar’s sea trade introduced artistic styles, subjects, and craft traditions from the Mediterranean and Near Eastern worlds—along with their cultural meanings—in greater quantities than ever before. Patrons increasingly looked to foreign models. The abandonment of traditional South Arabian religions gradually put an end to the temples and thus also to the production of works of art and dedications they had fostered and housed.

A market for perfumes and incense existed in the Near East and Egypt beginning at least in the first millennium BCE. Frankincense, a gum resin obtained from a small tree (Boswellia sacra), was prized for the fragrant smoke it produces when burned. Myrrh, likewise a gum resin from a small tree (Commiphora myrrha), was also used in incenses, but it was more often a component of medicines and perfumes.

These trees grow primarily in parts of eastern Africa, the southern Arabian Peninsula, and India, and their restricted natural occurrence contributed to their market value. Frankincense and myrrh were the most sought-after forms of incense in the Mediterranean world, hence their inclusion among the gifts offered by the Magi to the newborn Jesus.

Incense was an essential ingredient for temple ceremonies and funerary rites among cultures in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece, as well as in South Arabia itself. The Romans purchased these aromatics in enormous quantities, and the most extensive surviving accounts of the incense trade derive from Roman authors. Demand vastly exceeded supply.

The high prices paid for South Arabian aromatics resulted in part from the length and difficulty of the journey to far-flung markets. Initially, camels transported incense across the Arabian Desert to the eastern Mediterranean coast or the western shores of the Persian Gulf. From the beginning of the common era, maritime routes predominated. Ships ferried their precious cargo from ports along the southwest Arabian Peninsula to Egypt’s Red Sea coast, the Gulf of Aden, and the Indian Ocean.

Wealth created by the long-distance incense trade stimulated massive building projects such as city walls, palaces, and sanctuaries. Cities had one or more temples inside their walls and at least one that lay outside them. Temples were usually small, rectangular structures built of beautifully finished stone blocks, whose plan took two principal forms: courtyard temples, where the interior was divided in two, producing an enclosed space in the rear and an open courtyard nearest the entrance; and hypostyle temples, consisting of a single room supported by three or more rows of pillars, sometimes approached via a monumental gate.

The geometry and formal abstraction of temple design and decoration, echoed in the statuary of the period, emerge as characteristic elements throughout the first millennium BCE. Temples housed cult furnishings such as altars, which were used in rituals involving the pouring of libations. The burning of aromatics was also an important practice, and the discovery of animal bone remains from outside the Awam temple at Marib suggests either the offering of cooked meats or commemorative banquets.

Yemen’s ancient inhabitants worshiped a pantheon of deities both male and female, some of national and others of local significance. At Marib there were large sanctuaries dedicated to the god Almaqah, the national deity of the Sabaean kingdom, which were important pilgrimage destinations. One of them, the Awam temple, was among the earliest and was by far the largest in the Arabian Peninsula. Several objects in this exhibition were found in the Baran temple near Marib, which was also dedicated to Almaqah.

The large number of inscribed votive objects recovered from temples tells us a great deal about religious concepts and practices as well as politics and society. Men and women made dedications to a deity for a variety of purposes: to acknowledge military success, to ensure good health, to protect an individual’s herd of camels or other livestock. Texts concluded by placing the object of the dedication under the protection of a series of gods, listed in hierarchical order. At the head of these lists is consistently the god Athtar, who was the supreme god and was universally recognized. The names of subsequent deities vary according to the dialect of the inscription, and therefore according to social and political environments.

While many different deities were recognized, little is known about their identities and relationships with each other. Votive objects and their dedications indicate that religious feeling was a personal, intimate concept, focused on the individual’s relationship with the deity and not the separate world of the gods themselves.

Over ten thousand inscriptions survive in South Arabian, a Semitic language related to Arabic and Ethiopian. Scholars recognize four distinct dialects: Sabaean, Qatabanian, Hadramitic, and Minaean. The South Arabian script is based on an alphabet of twenty-nine consonants, in contrast to the twenty-two letters of the Phoenician alphabet from which the Greek alphabet was later derived. Inscriptions cover a period of some 1300 to 1400 years, which saw a gradual evolution of the script. During this long period, three or four stages in the script’s development can be identified.

The oldest known inscriptions consist of personal names incised on the walls of ceramic vessels. Monumental inscriptions, worked in relief, appeared around the seventh century BCE. Typically carved in beautiful, elegant styles of script, inscriptions are found on a remarkably wide range of objects, from buildings and funerary monuments to cult furnishings and votive objects. The major categories of texts are:

Prescriptive: decrees issued by rulers or a temple, for example

Religious: dedications, records of ceremonies or religious acts

Property claims: building houses or irrigation systems, defining values and ownership rights

Commemorative: records of military campaigns or great construction works

Over four hundred statue fragments were found during excavations at the Awam temple near Marib, dedicated to the Sabaean national deity Almaqah, of which this example is the largest and best preserved. The figure wears a skirt wrapped in front; the lion skin draped over his back with paws crossed over its chest resembles statues of the Phoenician god Baal Melquart and the Greek hero Herakles. On the chest are two inscriptions. A short one names the person depicted as “Madikarib.” The second, extending from the shoulders to the bottom of the skirt, dedicates”this man if bronze” to the god Almaqah.

A procession of six men brandishing bows as weapons and severed heads as trophies occupies the central panel of this relief plaque, which may have been mounted on the door of the Baran temple at Marib. Above the procession is a pair of winged bulls flanking a tree of life symbol, an image familiar in the royal art of the Assyrian Empire in northern Mesopotamia (circa 900-600 BCE) and later in that of the Achaemenid Persian Empire (circa 550-300 BCE).

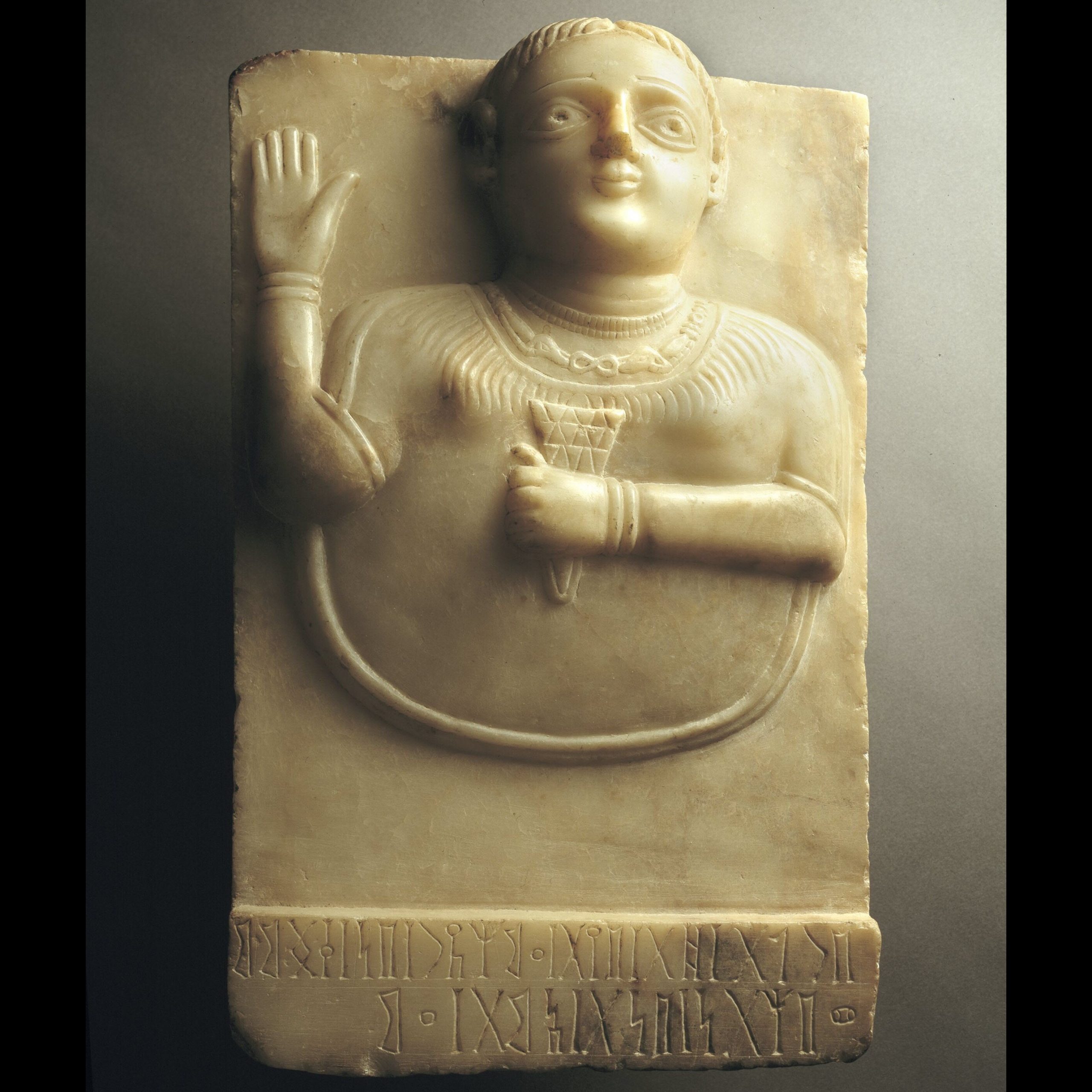

The earliest of the three statues of Awsan kings depicts a figure wearing a skirt wrapped in front, bracelets, a ring, and thonged sandals. He may have been the first of a dynasty in Awsan, as his father’s name does not include the title of king.

Exhibition Highlights

Statue of Yasuduqil Far, king of Awsan

Wadi Markha, 1st century BCE

Alabaster; H 70 W 31 TH 26 cm

National Museum, Aden, NAM 611

ELS2005.6.22

The earliest of the three statues of Awsan kings depicts a figure wearing a skirt wrapped in front, bracelets, a ring, and thonged sandals. He may have been the first of a dynasty in Awsan, as his father's name does not include the title of king.

Image 1 of 22

Statue of Madikarib

Marib, Awam temple, 6th century BCE

Bronze

H 93 W 27 H of head 15 cm

National Museum, Sanaa, YM 262

ELS2005.6.15

Over four hundred statue fragments were found during excavations at the Awam temple near Marib, dedicated to the Sabaean national deity Almaqah, of which this example is the largest and best preserved. The figure wears a skirt wrapped in front; the lion skin draped over his back with paws crossed over its chest resembles statues of the Phoenician god Baal Melquart and the Greek hero Herakles. On the chest are two inscriptions. A short one names the person depicted as "Madikarib." The second, extending from the shoulders to the bottom of the skirt, dedicates "this man of bronze" to the god Almaqah.

Image 2 of 22

Fragment depicting a military victory

Marib, Baran temple, 5th century BCE

Bronze

H 46 W 38 TH 1 cm

National Museum, Sanaa, YM 13981

ELS2005.6.17

A procession of six men brandishing bows as weapons and severed heads as trophies occupies the central panel of this relief plaque, which may have been mounted on the door of the Baran temple at Marib. Above the procession is a pair of winged bulls flanking a tree of life symbol, an image familiar in the royal art of the Assyrian Empire in northern Mesopotamia (circa 900-600 BCE) and later in that of the Achaemenid Persian Empire (circa 550-300 BCE).

Image 3 of 22

Rearing horse with Himyaritic inscriptions

Ghayman, 2nd–3rd century CE

Bronze; H 1.02 L 1.06 m

Dumbarton Oaks, BZ 1938.12

LTS2005.1

Image 4 of 22

Pair of lions with riders

Tamna, early 1st century BCE

mid-1st century CE

Bronze; each H 61 L 52.5 cm

American Foundation for the Study of Man,

Falls Church, Virginia TS 152A, TS 152B

LTS1992.6.87-.88

This pair of lion riders originally decorated a private house at Tamna, Qataban's capital. Inscribed in South Arabian, but with a subject drawn from Greek and Roman art and legend, they demonstrate the international taste of upper-class individuals in this important kingdom's urban centers. Cupids riding lions may be connected with the cult of the Greek god Dionysos, which enjoyed widespread popularity in southwest Asia in this period.

Image 5 of 22

Cornice with vine scroll

Marib, 2nd century CE

Alabaster

H 22.5 W 130 TH 7 cm

The British Museum, ANE 1966-12-13,1=134886

ELS2005.6.12

Image 6 of 22

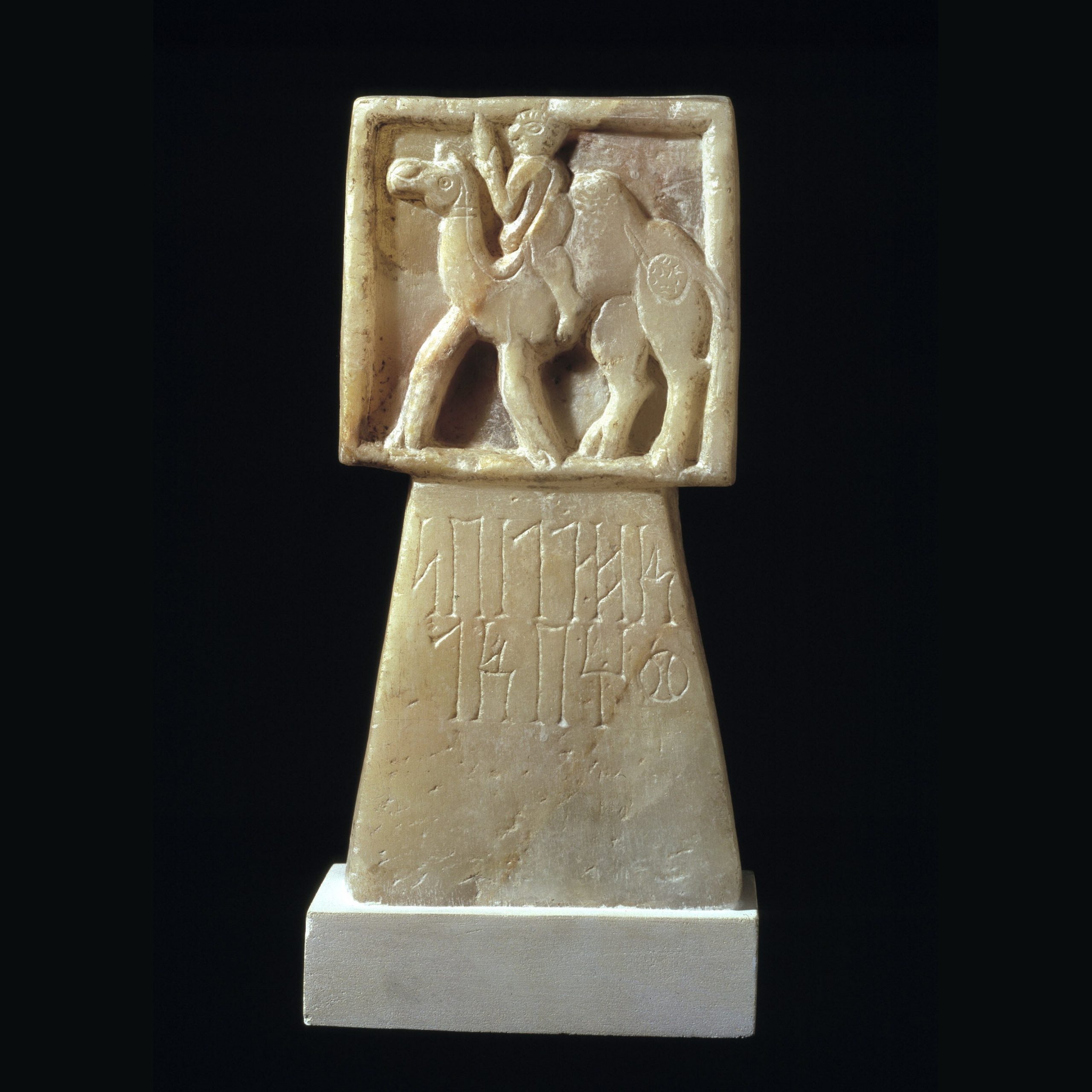

Incense burner showing a camel rider

Shabwa, ca. 3rd century CE

Alabaster

H 32 W 15 TH 8 cm

The British Museum, ANE 1937-5-7,1=125682

ELS2005.6.3

Image 7 of 22

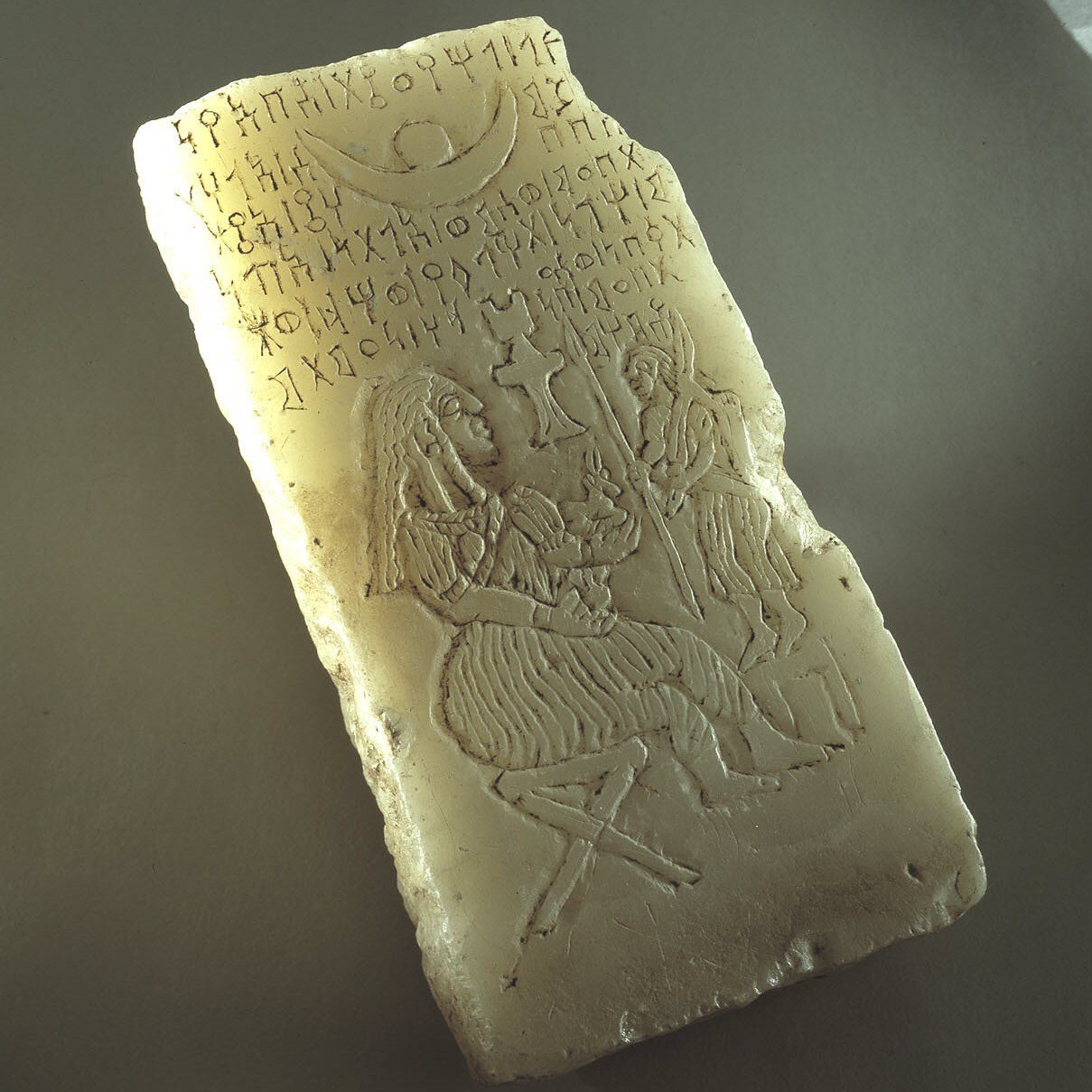

Stela depicting an offering to the sun goddess Shams

Tanim, circa 1st century CE

Alabaster; H 20.6 W 10.5 TH 4 cm

Lent by the National Museum, Sanaa, YM 386

ELS2005.6.25

Image 8 of 22

Jar and lid

Hajar ibn Humayd, mid-1st century BCE–2nd century CE

Alabaster; H 10.4 D 9.5 cm

American Foundation for the Study of Man,

Falls Church, Virginia TC HI 11

LTS1992.6.10

Image 9 of 22

Altar dedicated to the deity Rahmaw

Probably from Marib, 6th century BCE

Tin-bronze; H 66 W 110 TH 34.5 cm

The British Museum,

ANE 1970-6-4,1-2=135323 and 135324

ELS2005.6.8

This unique bronze altar carries part of an inscription describing how the altar was dedicated to a local deity named Rahmaw following completion of a successful hunting trip. The largest preserved portion consists of the front panel with three rows of standing sphinxes, set below a cornice around which the inscription runs.

Image 10 of 22

Inscribed hand dedicated to the god Talab

Provenance uncertain, 2nd–3rd century CE

Bronze

L 18.5 W 11 TH 3.6 cm

The British Museum, ANE 1983-6-26,2=139443

ELS2005.6.9

The right hand is traditionally regarded as a powerful symbol of good fortune, appearing as a protective motif on dedicatory inscriptions and emphasized

as a gesture of worshipers in statues and stelae.

Image 11 of 22

Inscribed bull dedicated to the goddess dhat-Himyam

Provenance uncertain,1st–2nd century CE

Bronze; H 21 L 28 W 9.7 cm

The British Museum, ANE 1971-2-27,1=135562

ELS2005.6.10

The inscription reads: "to dhat-Himyam, two bulls," indicating that this object was one of a pair.

Image 12 of 22

Ibex frieze

Marib, Baran temple, 5th century BCE

Alabaster; H 39 W 53 TH 35 cm

Marib Museum, BAR 906

ELS2005.6.93

Image 13 of 22

Necklace with amulet of the goddess al-Lat

Tamna, probably 1st century CE

Gold

Pendant H 3.4 W 4 TH 0.1, chain L 11.2 D 0.9 cm

American Foundation for the Study of Man, Falls Church, Virginia TC 19

ELS2005.6.2

Image 14 of 22

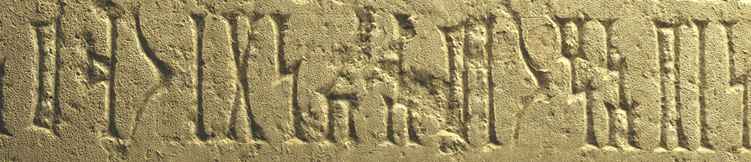

Inscription mentioning construction of a palace

Tamna, 3rd-2nd centuries BCE

Granite; H 50 W 106 TH 29 cm

Bayhan Museum, BaM 673

ELS2005.6.19

Image 15 of 22

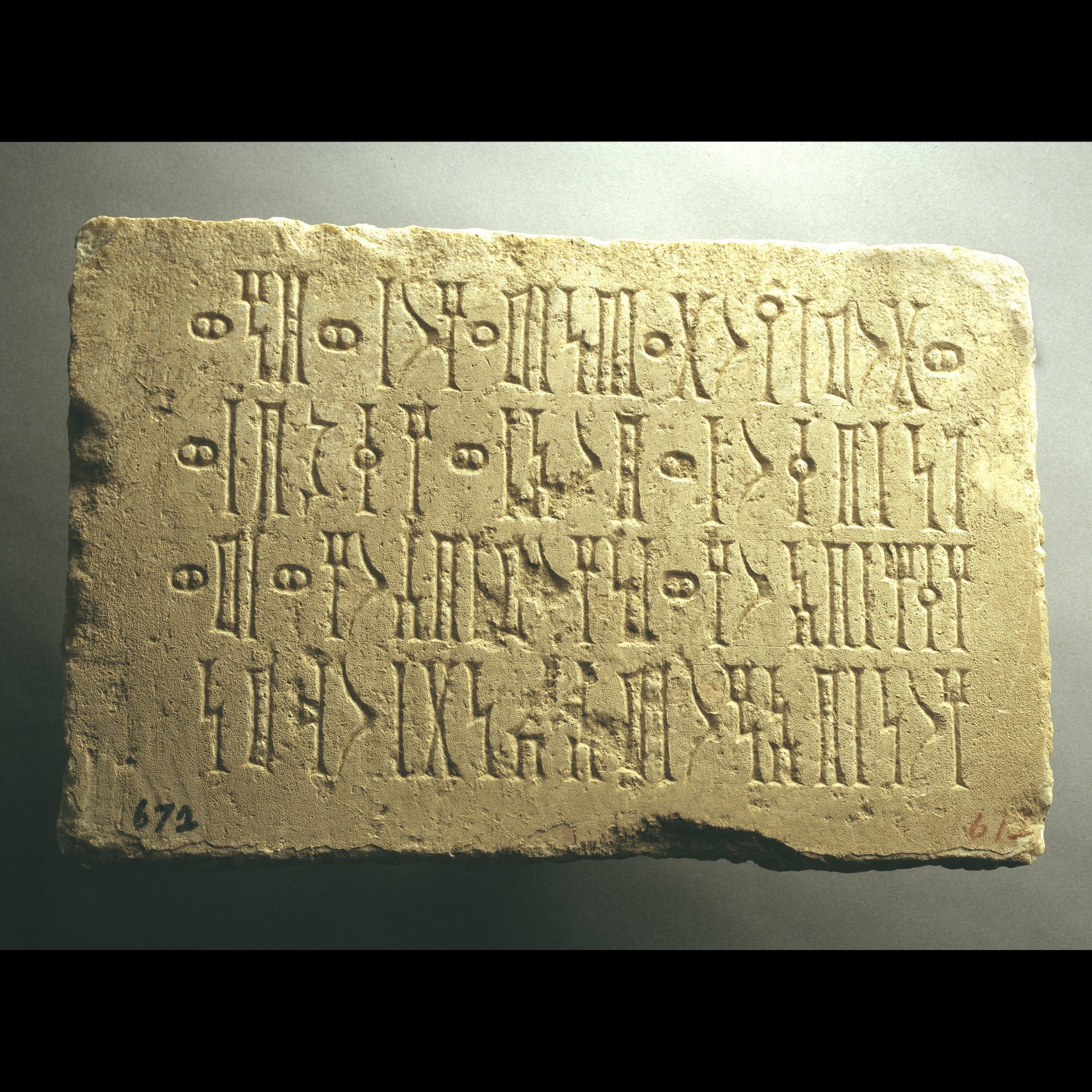

Stela commemorating the digging of a well

Wadi Akhirr, mid-1st century CE

Limestone; H 35 W 53 cm

Bayhan Museum, BAM 672

ELS2005.6.27

Image 16 of 22

Inscribed plaque with lamp extended by hand

Tamna, first half of 1st century BCE

Bronze; H 20.5 W 14.2 D 11.6 cm

American Foundation for the Study of Man, Falls Church, Virginia, TS 1121

LTS1992.6.49

This unique object was found in a private house at Tamna, Qataban's capital. In the dedication it is described as "a hand which is illuminated with an oil lamp and a dedication."

Image 17 of 22

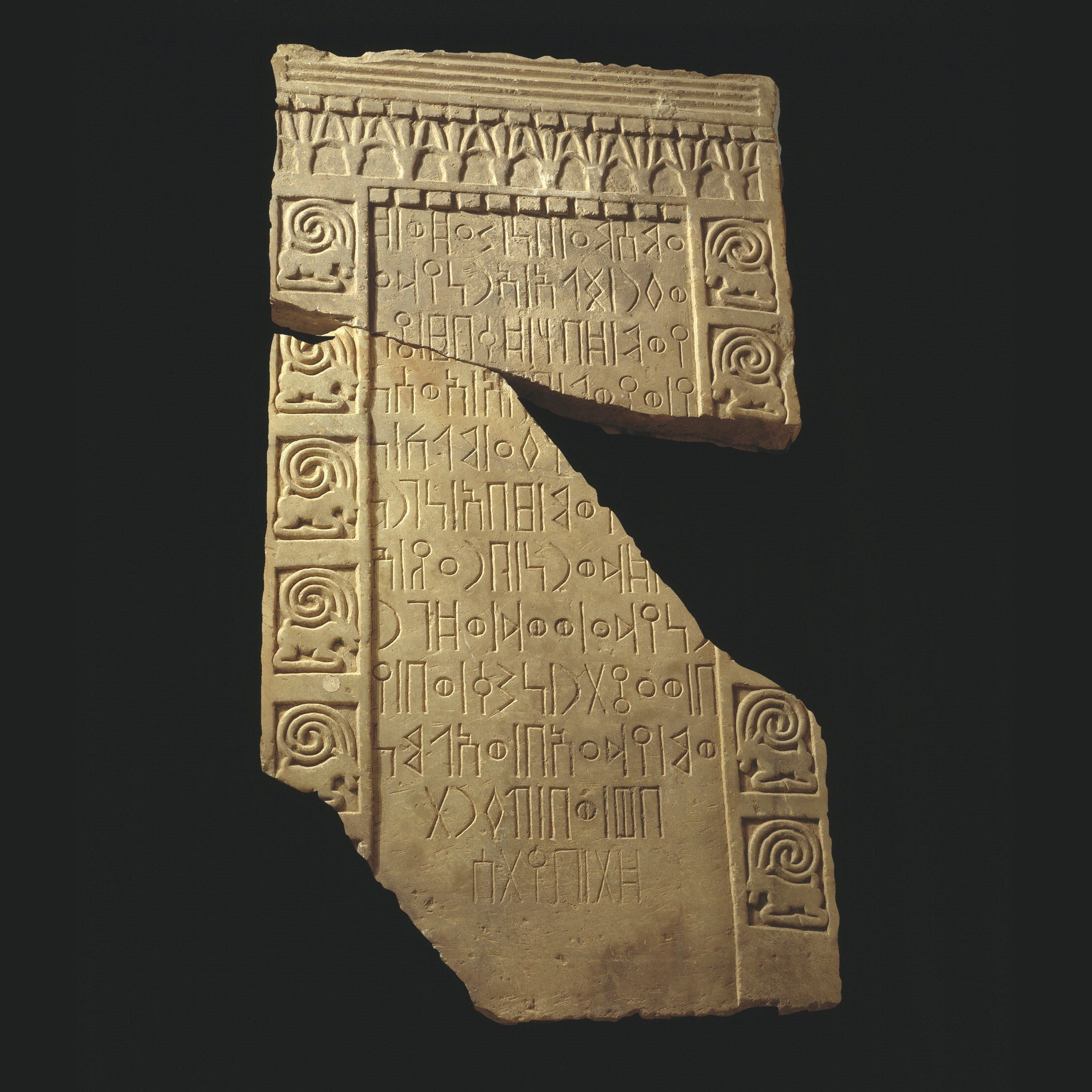

Inscription

As-Sawda, Aranyada temple, early 7th century BCE

Alabaster

H 80 W 63 TH 8 cm; H 48.5 W 63 TH 8 cm

National Museum, Sanaa, YM 11126 and 11192

ELS2005.6.18.1-2

Image 18 of 22

Funerary stela

Marib, 6th–4th centuries BCE

Limestone, alabaster, and gypsum

H 93 W 24.5 cm

Marib Museum, AW 98 A 2345

ELS2005.6.67

Image 19 of 22

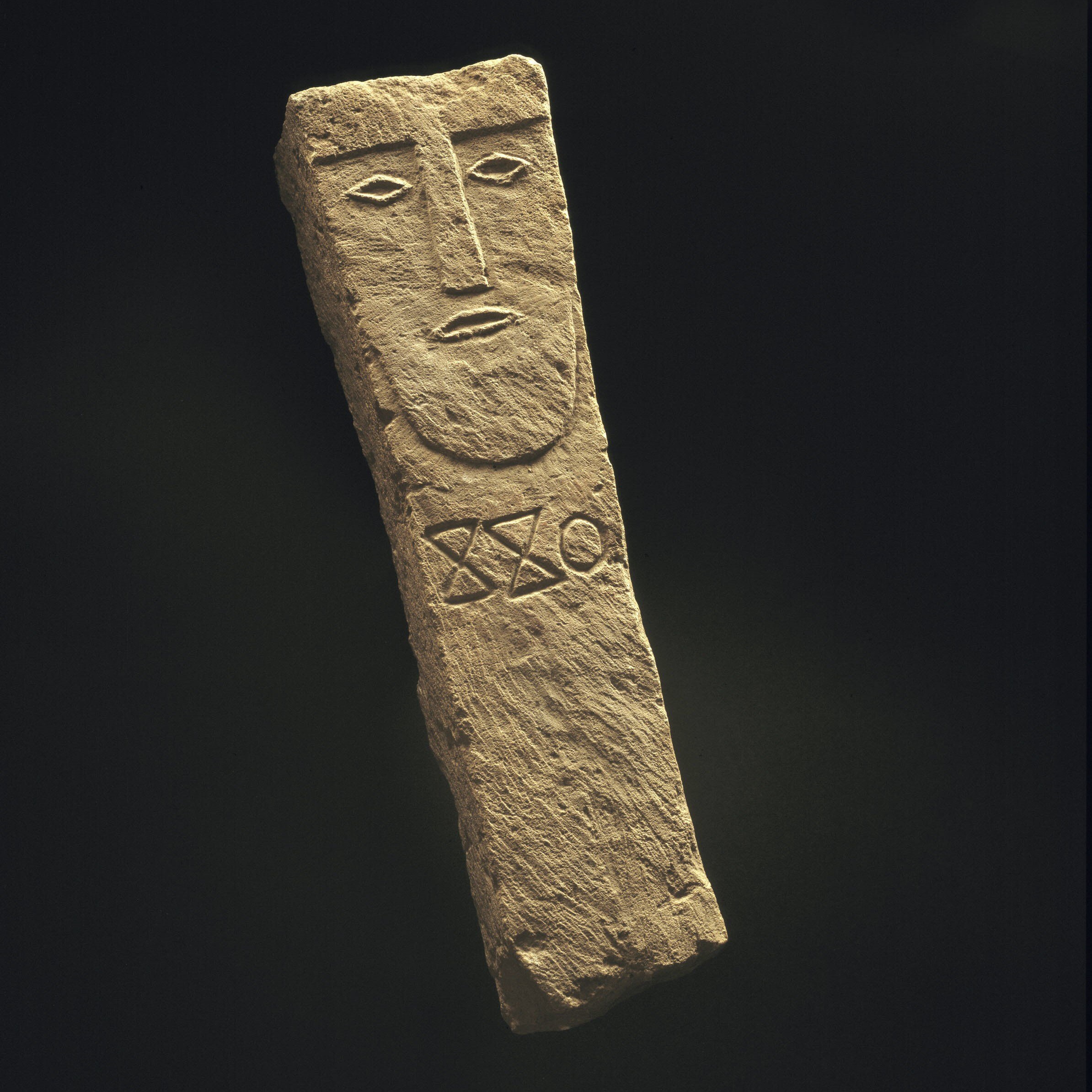

Funerary pillar stela

Possibly from the Jawf, ca. 5th–4th century BCE

Limestone; H 38 W 19 TH 8 cm

National Museum, Sanaa, YM 1121

ELS2005.6.68

Image 20 of 22

Stela depicting female holding a sheaf of wheat

The Jubah, 1st century BCE

Alabaster; H 53 W 34 TH 5.5 cm

National Museum, Sanaa, YM 71

ELS2005.6.94

Image 21 of 22

Statue of a standing male figure

Provenance uncertain, possibly 3rd–1st century BCE

Alabaster; H 16 W 18 D 8 cm

The British Museum, ANE 1907-1-12,5=102461

ELS2005.6.13

Image 22 of 22

Detail, Pair of lions with erotes as riders; Figure; early 1st century BCE-mid 1st century CE; Bronze; Yemen; Gift of The American Foundation for the Study of Man (Wendell and Merilyn Phillips Collection); Arthur M. Sackler Gallery S2013.2.77.1-2.

- Jump To...