August 20, 2011–August 19, 2012

-

Dates

-

Location

Freer Gallery of Art

-

Collection Area

American Art

In Victorian England in the nineteenth century, life was separated into gendered spheres. The masculine realm was often characterized by outward-directed activities of physical exertion, industry, and business. Women, on the other hand, were identified with the private world of imagination and self-reflection, as seen in this selection of prints by American expatriate artist James McNeill Whistler. Images of private, enclosed spaces, inhabited by quiet, self-contained figures, recur from his earliest etchings in the mid-1850s to his later watercolors and lithographs. Family members, close friends, or the artist’s current mistress almost always serve as the focus of these interior scenes. This sense of intimacy is underscored by the works’ small scale, which compels the viewer to stand close and study the scene carefully. Whistler’s interiors thus encourage us to retreat—like his subjects—into a realm of “sweet silent thought.”

Whistler’s Interiors

At the age of twenty-one Whistler made a self-conscious and deliberate decision to become a professional artist. When he left the United States for France in 1855, he associated himself with Gustav Courbet, Charles Baudelaire, and other avant-garde painters and poets in Paris. He also maintained a close relationship with his half-sister Deborah Haden and her family in London. In 1858, at the urging of Deborah’s husband, the surgeon and amateur etcher Francis Seymour Haden, Whistler began a series of etchings in which figures read, play music, or daydream in a domestic interior.

At the age of twenty-one Whistler made a self-conscious and deliberate decision to become a professional artist. When he left the United States for France in 1855, he associated himself with Gustav Courbet, Charles Baudelaire, and other avant-garde painters and poets in Paris. He also maintained a close relationship with his half-sister Deborah Haden and her family in London. In 1858, at the urging of Deborah’s husband, the surgeon and amateur etcher Francis Seymour Haden, Whistler began a series of etchings in which figures read, play music, or daydream in a domestic interior.

In the nearly half-century that followed, Whistler’s artistic style underwent a significant change. He detached himself from the realism of Courbet, embraced the “art for art’s sake” ideals of British aestheticism, and developed an increasingly abstract approach to representation. He also continued to explore and refine favorite motifs. Images of reading and making music allowed Whistler to depict figures whose concentrated attention seems to block out the surrounding world.

Whistler was also fascinated by the sense of reverie conveyed by pensive women in languid poses. A drawing of young Weary of the artist’s mistress Jo Hiffernan exemplify this interest. The late lithograph Nude Model, Reclining, the woman seems unaware of being observed, while the artist’s presence is implied by a sketchy, evocative touch. Some of Whistler’s earliest studio images, however, are constructed as self-portraits that give the viewer a “behind-the-scenes” glimpse of the generally private spaces in which concentrated attention, associated with both reverie and artistic creativity, is exercised.

All of these works are by the American expatriate artist James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) and are the Gift of Charles Lang Freer.

Harmony in Green and Rose: The Music Room

1860–61

Oil on canvas

F1917.234

Whistler began work on this painting shortly after he moved from Paris to London in 1859. Originally known as The Morning Call, it is set in the Haden home on Sloane Street. The image of the artist’s half-sister Deborah Haden, who plays the piano, is reflected in the mirror to the left. Her daughter Annie reads in a chair. Isabella Boott, a family friend, pauses in the center of the room.

The figures occupy a slightly claustrophobic space and are strangely disengaged from one another. A sense of uneasiness is underscored by the way the floor seems to tilt forward when in reality it should recede. That the painting ultimately achieves visual coherence is due to the decorative unity created by the bold colors and the repeated pattern of the chintz draperies.

Keep Exploring

-

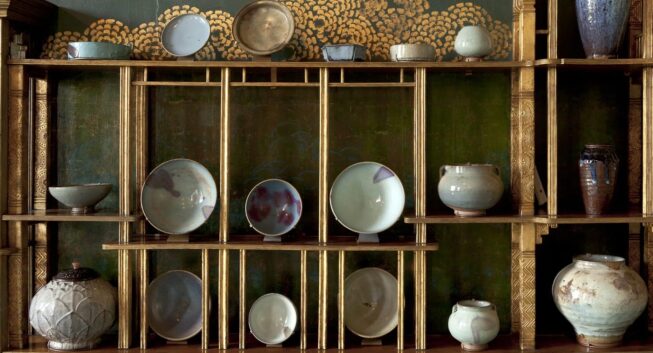

A Perfect Harmony

November 27, 2019–October 8, 2023

-

The Peacock Room Comes to America

September 3, 2022–ongoing

-

Whistler in Watercolor

May 18, 2019–November 3, 2019

- Jump To...

Explore All Pieces in this Section

Nelly

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Pencil on white paper

-

Accession

F1898.158

The Slipper

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Etching; ink on paper

-

Accession

F1898.253

Violet and Amber–Tea

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Watercolor on paper

-

Accession

F1902.162a-c

Bravura in Brown

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Watercolor on paper

-

Accession

F1902.167a-c

The Music Room

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Etching; ink on paper

-

Accession

F1898.249

The Slipper

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Etching; ink on paper

-

Accession

F1898.252

Pink Note–The Novelette

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Watercolor on paper

-

Accession

F1902.158a-c

Baby Leyland, Reading

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Crayon and pastel on brown paper

-

Accession

F1905.149a-b

Seymour Haden Playing the Cello

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Pencil, pen and ink on beige paper

-

Accession

F1898.160

Resting in Bed

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Watercolor on paper

-

Accession

F1907.172a-c

Harmony in Green and Rose: The Music Room

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Oil on canvas

-

Accession

F1917.234a-b

Nelly

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Chalk on blue laid paper

-

Accession

F1898.159

Annie, Seated

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Etching; ink on paper

-

Accession

F1898.246

Weary

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Drypoint; ink on paper

-

Accession

F1898.329

La Belle Dame Endormie

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Ink on paper

-

Accession

F1906.183

Au Sixième

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Etching; ink on paper

-

Accession

F1898.410

An Artist in His Studio

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Pen and ink and pencil on paper

-

Accession

F1906.104

Nude Model, Reclining

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Ink on paper

-

Accession

F1906.163

Reading by Lamplight

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Etching and drypoint; ink on paper

-

Accession

F1898.247

Reading by Lamplight

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Etching and drypoint; ink on paper

-

Accession

F1898.247

Reading by Lamplight

-

Geography

United States

-

Material

Etching and drypoint; ink on paper

-

Accession

F1898.247

Steel anvil with removable wood handle, formerly owned by Whistler

-

Geography

United Kingdom

-

Material

Steel, wood

-

Accession

F1908.237

Steel hammer, with removable wood handle, formerly owned by Whistler

-

Geography

United Kingdom

-

Material

Steel, wood

-

Accession

F1908.238