Ascetics, often termed “yogis” and “fakirs” in India, piqued Europeans’ interest in the seventeenth and eighteenth century with their otherworldly, naked appearance; their fearful, militaristic “troops”; and their awesome practices of self-denial, known as “austerities,” to gain supernatural powers or merit with the gods. Europeans often interpreted these acts as fanaticism or compared them to Christian penitential practices to atone for sins.

The French gem merchant Jean-Baptiste Tavernier illustrated a popular meeting spot for ascetics under a banyan tree in “Of the Faquirs … and of their Pennances” as early as 1676. He carefully cataloged their extreme postures, including holding their arms frozen above their heads or staring at the sun for years on end. Amazed by such “incredible… penance,” Tavernier was also suspicious that “for being worship’d as Saints, they have in their hands all opportunities of doing evil.”

The print was quickly appropriated by other engravers, such as Bernard Picart, whose renowned version of the ascetics’ “severe Penances” is on view in the Yoga exhibition and here in a copy by Claude du Bosc, titled “Divers Pagods and the Penitence of the Faquirs,” from 1733. Picart, though, with the publisher Jean-Frédéric Bernard, incorporated new details to offer a more comprehensive view of Indian religious practice toward a goal of understanding all the world’s religions. For instance, he added a central Jain ascetic who practiced non-violence (ahimsa) by covering his mouth and sweeping the earth to avoid injuring living things.

Both Tavernier’s and Picart’s prints were regularly copied over more than a hundred years, such as by Thomas Salmon in the 1731 “Indian pagodas and the bodily torments of Fakirs” and by Thomas Maurice in his Indian Antiquities, published in 1800.

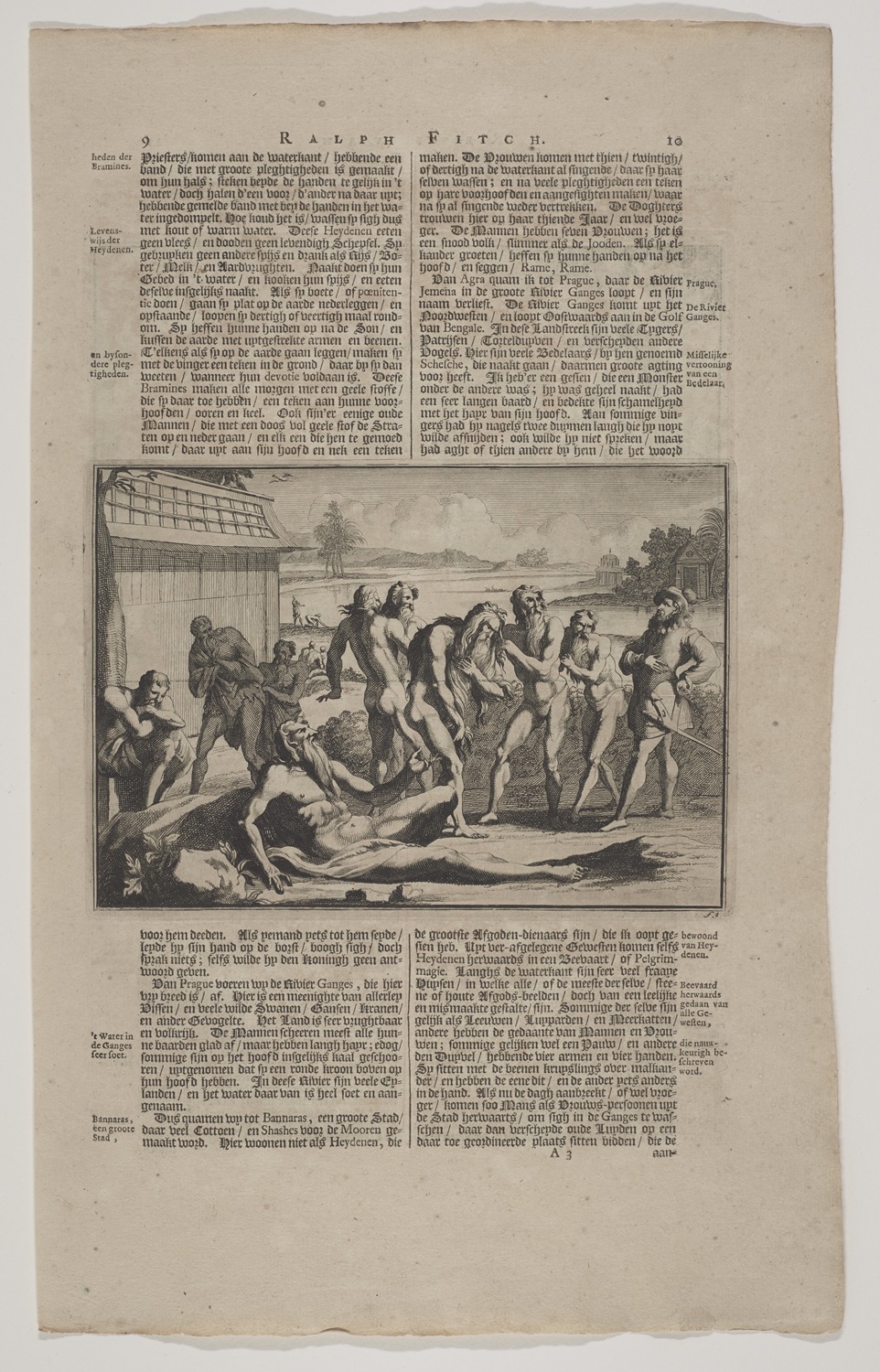

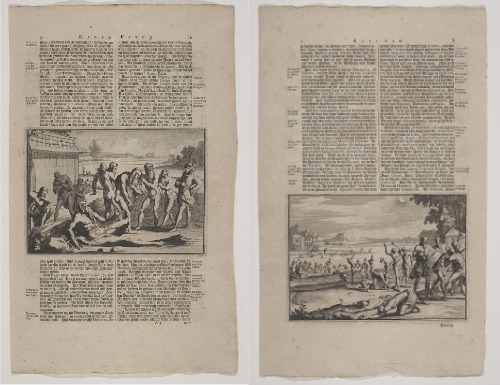

In the early 1700s, the prolific Dutch publisher Pieter van der Aa compiled travel accounts from the previous three centuries into multivolume sets that documented the world with the aid of engraved maps and illustrations. These two prints, which faced each other in the book, are from a section devoted to the voyages of the English, or Voyagien der Engelsen. They specifically illustrate the Dutch translation of Journey to India over-land by the British merchant Ralph Fitch, published in 1583. Fitch interpreted the scenes in the left-hand print as “strange ceremonies,” such as Indian pilgrims bathing in the river Ganges and performing “penance” through “prostrations” to the sun and earth. The right-hand print actually shows Fitch observing an ascetic “who never spake,” likely having taken a vow of silence. Though naming him a “monster among the rest” of the “beggars,” Fitch intimately detailed the ascetic’s figure, describing him as having “hair… so long and plentiful, that it covered his nakedness” and “nails… two inches long, as he would cut nothing from him.”

In the early 1700s, the prolific Dutch publisher Pieter van der Aa compiled travel accounts from the previous three centuries into multivolume sets that documented the world with the aid of engraved maps and illustrations. These two prints, which faced each other in the book, are from a section devoted to the voyages of the English, or Voyagien der Engelsen. They specifically illustrate the Dutch translation of Journey to India over-land by the British merchant Ralph Fitch, published in 1583. Fitch interpreted the scenes in the left-hand print as “strange ceremonies,” such as Indian pilgrims bathing in the river Ganges and performing “penance” through “prostrations” to the sun and earth. The right-hand print actually shows Fitch observing an ascetic “who never spake,” likely having taken a vow of silence. Though naming him a “monster among the rest” of the “beggars,” Fitch intimately detailed the ascetic’s figure, describing him as having “hair… so long and plentiful, that it covered his nakedness” and “nails… two inches long, as he would cut nothing from him.”