October 29, 2005–January 22, 2006

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

Ancient Near Eastern Art

“Style and Status: Imperial Costumes from Ottoman Turkey” was the first international exhibition devoted to sumptuous and graphically stunning imperial Turkish robes (kaftans) from the 16th and 17th century—the embodiment of the maxim that “clothes make the man.” This exhibition presented robes that dazzle with their audacious play of colors, bold designs, and rich finish.

At the core of the 68 objects on view was a group of opulent imperial robes from the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul, Turkey, the largest repository of Islamic textiles in the world. Additional works were on loan from the Mevlana Museum, Konya, Turkey, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, and several national collections.

Broadly organized according to technique, the exhibition celebrated Ottoman artistic creativity and its success at transforming silk into the most potent and visible symbol of the empire’s power and wealth. Many of the robes were exhibited on custom-made mannequins that show off their full splendor. In addition to robes belonging to Sultan Selim (reigned 1512–1520), Sultan Suleyman (reigned 1520–1566) and his son Bayazid, who was executed in 1561, the exhibition included trousers, hats, cushion and floor coverings, as well as several large, inscribed textiles from the Topkapi’s renowned collection. Examples of ecclesiastic copes and chasubles made from Ottoman silks and velvets were also on display.

No phrase more appropriately describes the dazzling effect of Ottoman robes (kaftans) as the foremost items of personal luxury in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Turkey. Their bright colors, bold designs, and ample shapes conveyed a sense of imperial splendor that became synonymous with the artistic, cultural, and political ideals of the Ottoman Empire (reigned 1281-1924). The Ottomans were not alone in recognizing the importance of precious fabrics, which were considered an indispensable commodity throughout the Islamic world. They succeeded in developing a distinct language of design or “brand” to express the Ottoman ideology of power to friends and foes alike.

No phrase more appropriately describes the dazzling effect of Ottoman robes (kaftans) as the foremost items of personal luxury in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Turkey. Their bright colors, bold designs, and ample shapes conveyed a sense of imperial splendor that became synonymous with the artistic, cultural, and political ideals of the Ottoman Empire (reigned 1281-1924). The Ottomans were not alone in recognizing the importance of precious fabrics, which were considered an indispensable commodity throughout the Islamic world. They succeeded in developing a distinct language of design or “brand” to express the Ottoman ideology of power to friends and foes alike.

The Ottomans offered silk and as diplomatic gifts to cement political relationships and affirm their power and wealth. Within the realm, silk was used to compensate loyal subjects and confer rank and status. The symbolic importance of silk is even echoed in the language and rituals of the court: high officials “kissed the hem of the sultan’s garment” to show their allegiance and respect, while the ruler himself was said to don “the mantle of authority.” Silk ranked as one of the most important forms of artistic expression-the ultimate embodiment of style and status.

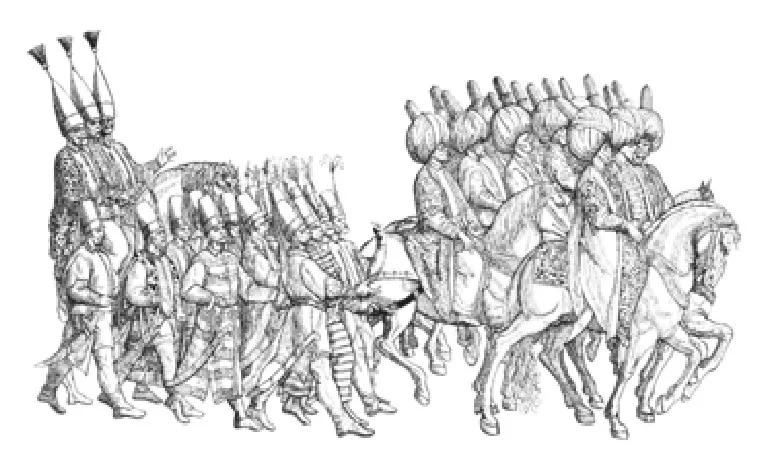

As the Habsburg ambassador at the Ottoman court in the mid-sixteenth century, Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq had daily opportunities to compare European and Ottoman fashion.

The Turks were quite as much astonished at our manner of dress as we of theirs. They wear long robes which reach almost to their ankles, and are not only more imposing but seem to add to their stature; our dress on the other hand, is so short and tight that it discloses the form of the body, which would be better hidden, and is thus anything but becoming, and besides, for some reason or other, it takes away from a man’s height and gives him a stunted appearance.

Most men and women in the Ottoman Empire wore loose, front-opening robes and wide trousers. A person’s gender and status largely determined the choice of accessories, such as jewelry, sashes, and especially headgear.

“Layering” was a main feature of Ottoman dress. Apart from protecting against the cold, wearing several layers also muffled the shape of the body and lent it bulkier proportions as well as a sense of grandeur. Since the number and type of layers indicated an individual’s social and economic status, Ottoman robes were designed and arranged specifically to reveal the layers underneath. Open necklines and side slits intentionally exposed a robe’s lining and the fine fabric of undergarments.

One of the most important uses of silk fabrics was their distribution as “robes of honor” (hil’at), a term derived from the Arabic khil’at in the West. The practice played a pivotal role in maintaining Ottoman political hierarchy within the empire and strengthened military and economic relations with foreign powers.

Distributed by the sultan or one of his representatives, robes of honor were intended to mark special occasions, such as the birth of a prince, the success of a military campaign, or holy days in the Muslim calendar. Silk kaftans were also offered as diplomatic gifts, as reward for a particular service, as commemoration of a new appointment, or as part of an individual’s salary and compensation.

Both foreign diplomats and local officials were fully aware of the robes’ symbolism as an indication of their rank and status. The number of robes, their fabric, and whether they were lined with fur signified the honor conferred on an individual. Among the most prestigious robes of honor were those made from gold cloth (seraser) or Italian velvet. Religious dignitaries received woolen ones because they disapproved of silk as a sign of human vanity.

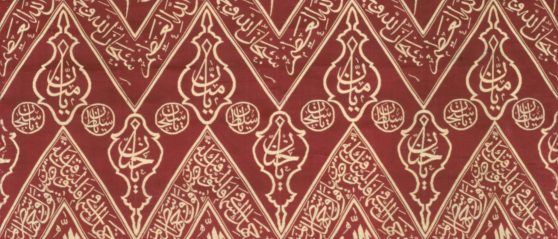

To mark the death of a sultan, most of the deceased’s clothing was tagged and stored away; other pieces were kept in his tomb. Brocaded silks, inscribed with verses from the Koran in a distinct zigzag pattern, frequently were draped over the sarcophagus.

The new sultan, usually the son of the deceased, presided over the ceremony wearing an unadorned robe made of satin or mohair in the preferred colors for mourning: black, deep blue, or purple. He wore the same robe for his accession ceremony, which followed immediately to assure smooth succession to the throne and to fend off any possible dissension.

- Jump To...