October 23, 2010–April 17, 2011

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

Arts of the Islamic World

This exhibition celebrates the millennium of the poet Firdawsi’s Shahnama (Book of Kings), considered one of the world’s great works of literature. Composed of more than 100,000 lines, the epic poem recounts the history of Iran from the beginning of time to the conquest of Islam in the seventh century. The Shahnama‘s sweeping narrative and colorful mix of myth and history have inspired the remarkable manuscript paintings on view. Created in the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, these illustrations convey the visual power of Firdawsi’s words. The exhibition is organized by the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery with support from The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund.

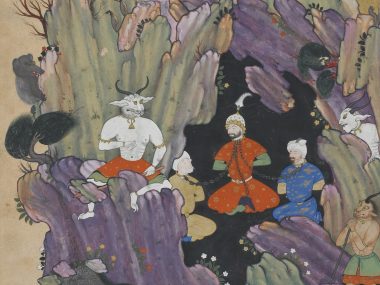

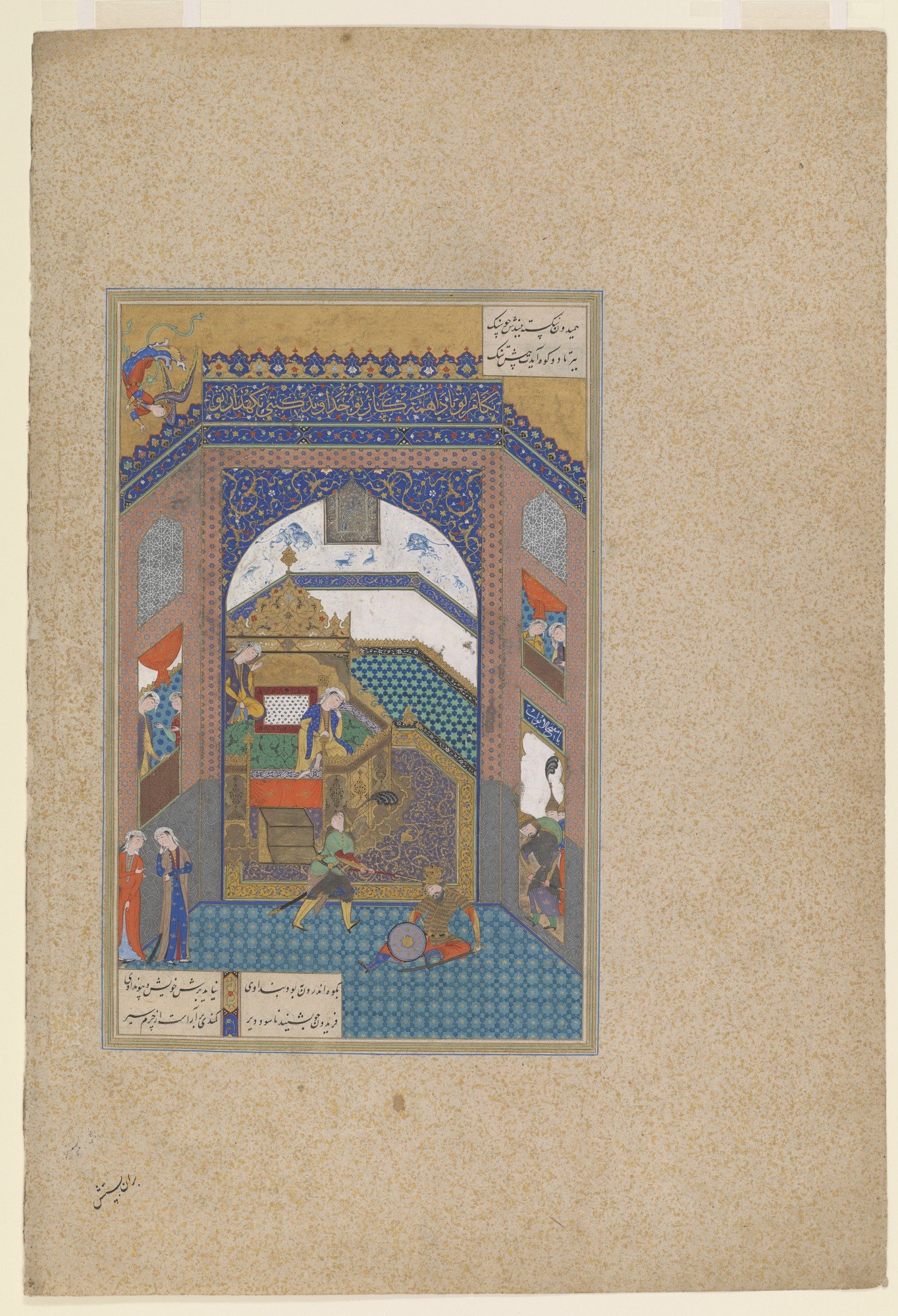

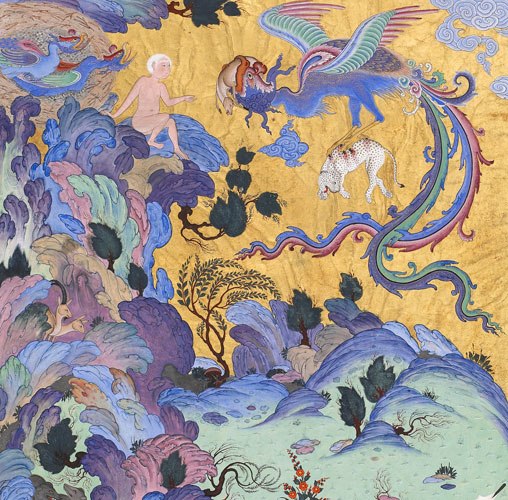

Kayumars Enthroned

Iran, Shiraz, Safavid period, 1518.

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Purchase—Smithsonian Unrestricted Trust Funds, Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, and Dr. Arthur M. Sackler

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery S1986.58.1

According to Firdawsi, Kayumars was the first ruler of Iran. His thirty-year reign was a period of peace and civility, when man and beast coexisted in blissful harmony. One distinguishing trait of Kayumars’ rule was the leopard-skin garments worn by the king and his men.

In this early sixteenth-century illustration, the king is proudly surrounded by his subjects and several tamed animals, humorously epitomized by the docile boar kneeling in the lower left corner. This tranquility is shattered when evil enters the world and the Black Demon (div-i siyah) kills Kayumars’ son Siamak. Such a horrific event initiates a series of confrontations between valiant kings and the forces of evil, which tested the loyalty, resolve, and strength of epic heroes.

Image 1 of 15

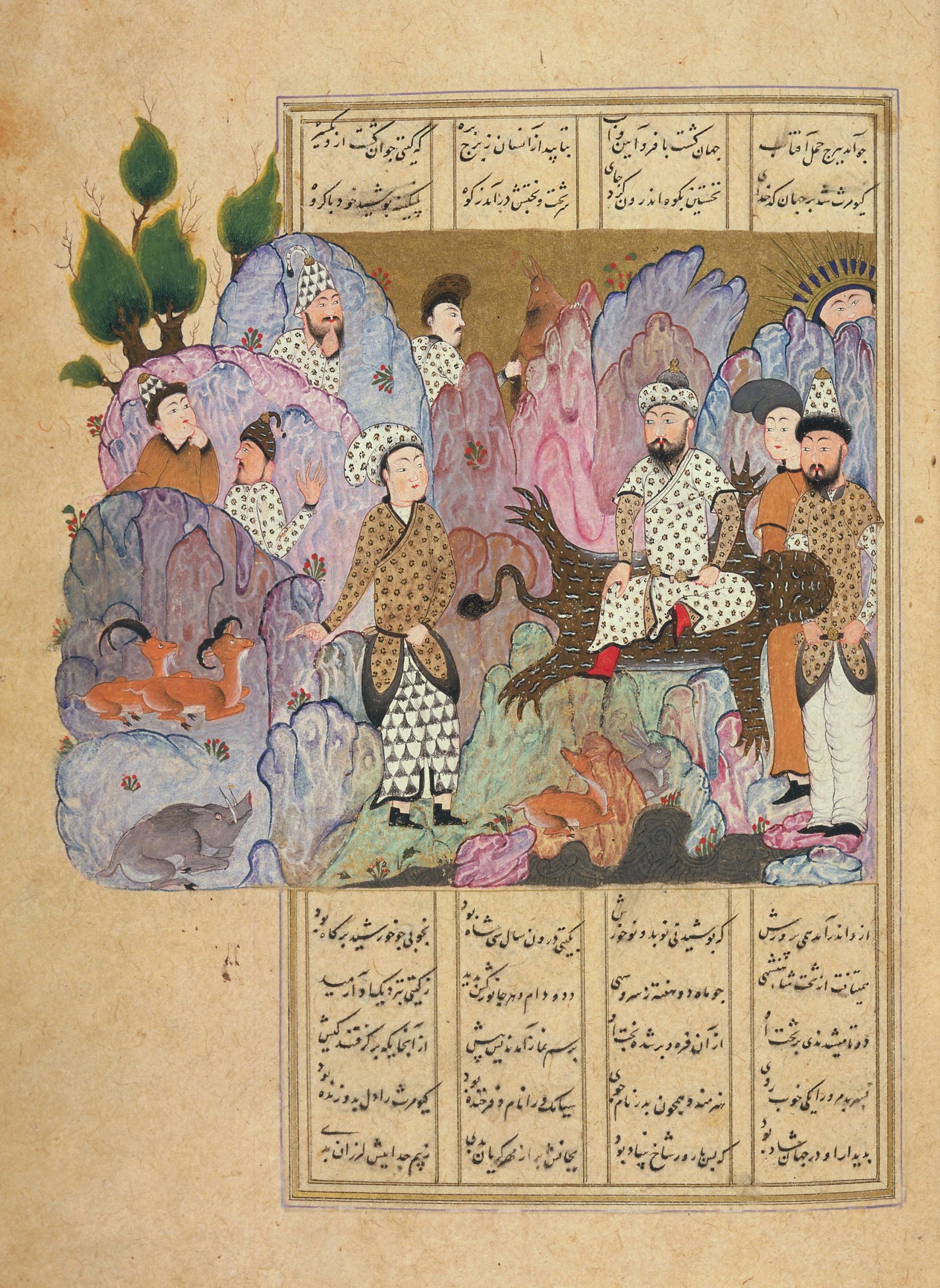

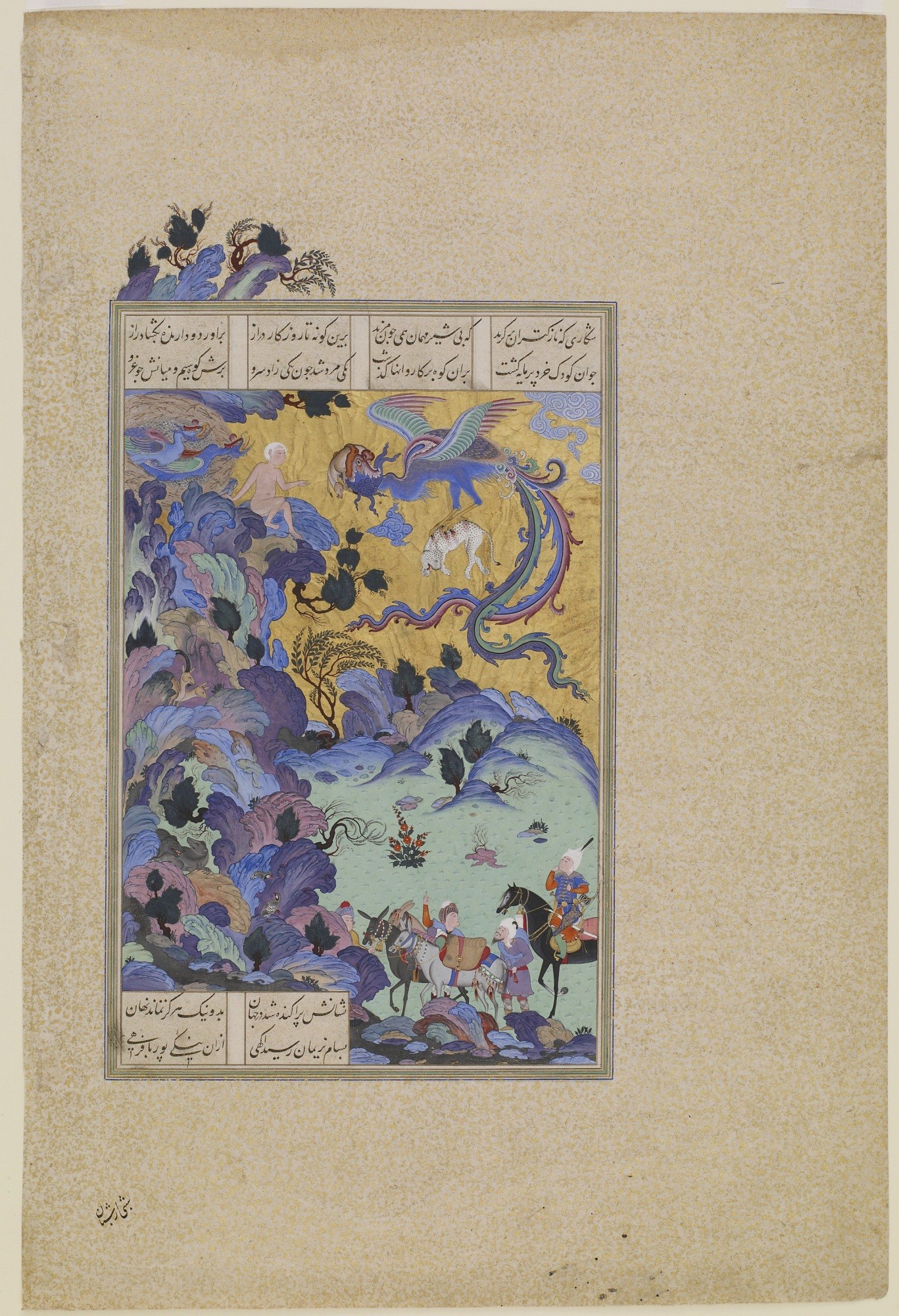

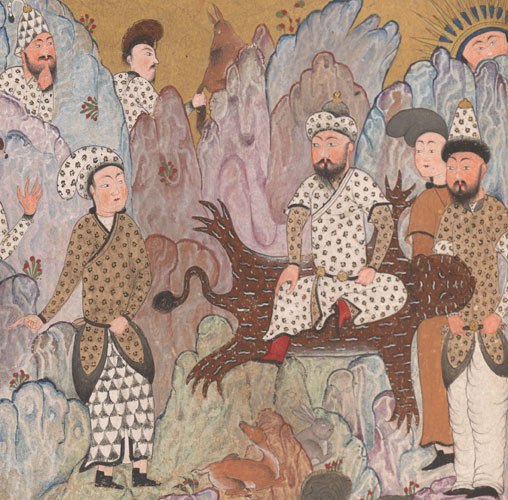

Hushang Slays the Black Div

Iran, probably Shiraz, Timurid period, 1441

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Lent by the Art and History Collection LTS1995.2.24

This lively composition may be the earliest depiction of Hushang, the grandson of Kayumars, the first Iranian king. Accompanied by angels, demons, and soldiers who anxiously watch from behind craggy mountains, the young hero bravely slays his supernatural enemy, the Black Demon (div-i siyah). The painting’s heightened sense of drama and excitement extends into the left margin, where a swooping angel brings a second demon to its knees.

Image 2 of 15

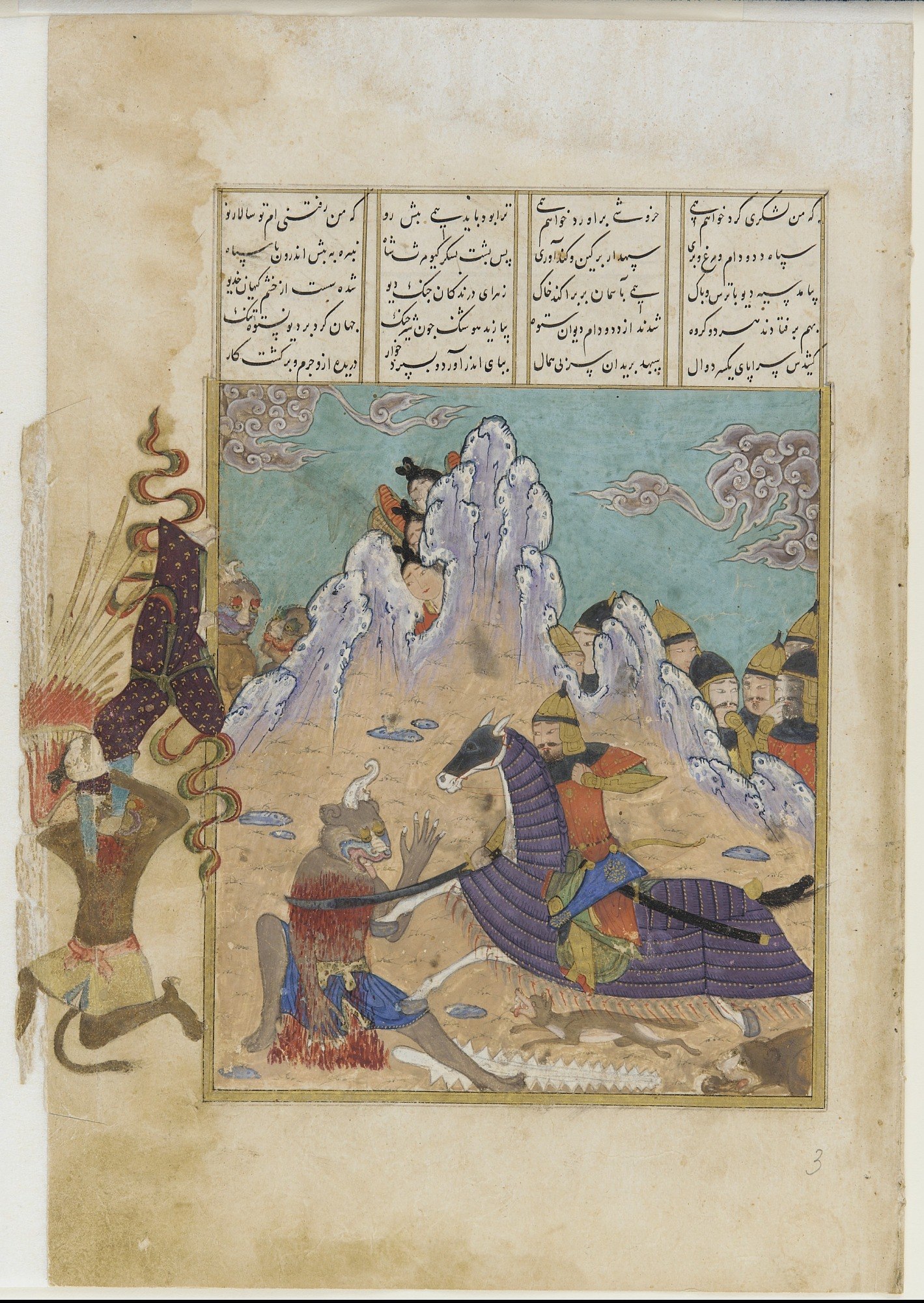

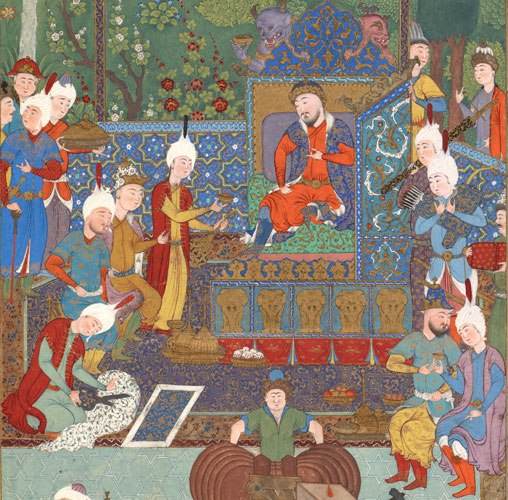

The Court of Jamshid

Iran, Tabriz, Safavid period, 1520s

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Lent by the Ebrahimi Family Collection

King Jamshid, who ruled for three hundred years, ushers in the first golden age in Iran’s history. He introduces to his people the sciences, medicine, and the arts and crafts, and he establishes Now-ruz (New Day) on the first of Farvardin (21 March), when he finally rests from his endeavors. Soon, however, Jamshid becomes increasingly arrogant about his achievements and considers himself better than everyone, even God. His hubris eventually causes him to lose his divine glory (farr), an essential attribute of Persian kingship, and he is killed by the evil Zahhak.

In this composition, Jamshid, dressed in sumptuous sixteenth-century attire, is flanked by two demons as he presides over a bustling court, where men weave silk, cut cloth, saw wood, and forge iron with huge bellows. The richly detailed surfaces and exuberant vegetation seem to reverberate with the excitement of Jamshid’s accomplishments.

The painting belongs to the most celebrated copy of the Shahnama, completed for the Safavid ruler Shah Tahmasp (reigned 1524-76). The manuscript’s 258 illustrated folios embody the ideals of Persian manuscript painting, as seen here in the emphasis on a meticulously balanced composition, jewel-like surfaces, and superb draftsmanship.

Image 3 of 15

Zahhak Enthroned

Ascribed to Mir Zayn al-Abidin

Iran, Qazvin, Safavid period, ca. 1576–77

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Lent by the Art and History Collection LTS1995.2.70

The gray-bearded figure is none other than the tyrannical Zahhak, who kills his own father to become king. After he usurps the throne, the devil (iblis) enters Zahhak’s court and kisses the king on the shoulders. Immediately, two snakes that only eat human brains grow from the spots.

Curiously, the writhing snakes, a symbol of Zahhak’s cruel nature, are absent from this illustration. The elegant court scene follows a key moment in the Shahnama, when Zahhak dreams of the yet-unborn Faraydun who will one day defeat him and bring his thousand-year reign of terror to an end. Obsessed with finding and killing Faraydun, Zahhak gathers his noblemen to ask for their support in raising an army.

This illustration was originally part of a Shahnama prepared for the Safavid ruler Ismail II (reigned 1576–77), the son and successor of Shah Tahmasp. Ismail II’s reign was marred by bloodshed and oppression, and he was murdered after only one year on the throne.

Image 4 of 15

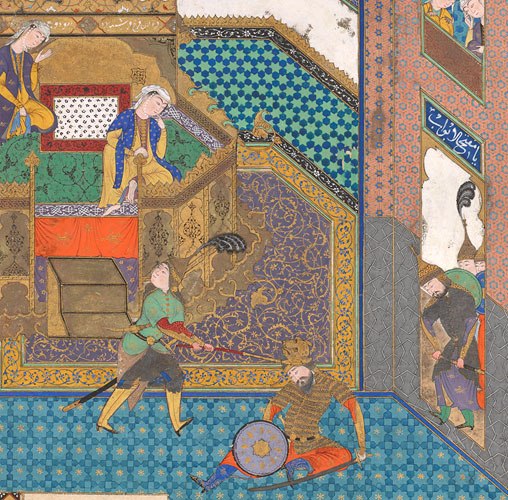

Faraydun Strikes Zahhak with the Ox-headed Mace

Attributed to Sultan Muhammad

Iran, Tabriz, Safavid period, ca. 1525

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Purchase, Freer Gallery of Art F1996.2

As predicted in Zahhak‘s dream, Faraydun pursues the tyrant to end his evil reign. When he arrives at Zahhak’s deserted palace, Faraydun releases King Jamshid’s imprisoned sisters (seen in the center section) and places himself on Zahhak’s throne. News of his overthrow reaches Zahhak, and the enraged sorcerer-king rushes back from India to kill Faraydun, but as was foretold, the youthful hero strikes him down. Faraydun is about to deliver a second—and fatal—blow with his ox-headed mace when the angel Surush swoops down (top left) and announces, “His time has not yet come.” Surush tells Faraydun to put Zahhak in chains and take him to a deep cave, where he will perish alone.

Anchored by a heavy, off-centered throne, the interior space is animated with fine geometric tiles and tight, swirling scroll designs that accentuate the dramatic moment of Faraydun’s victory over Zahhak, and by extension, the triumph of justice over tyranny—a central theme in the Shahnama.

Image 5 of 15

Zal Is Sighted by a Caravan

Attributed to Abdul Aziz

Iran, Tabriz, Safavid period, ca. 1525

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Lent by the Art and History Collection LTS1995.2.46

Zal, the father of the hero Rustam, was “born with a body like pure silver … but his hair was that of an old man.” An albino at birth, Zal’s snow-white hair was considered an ill omen, and the newborn was left in the wilderness. Fortunately, the infant was rescued by the simurgh, a fantastic creature that raises Zal in a nest with her own fledglings. Some time later, travelers passing through the region are amazed to find “a noble youth” living in the mountains. In this remarkable composition, Zal perches on top of a surging rock just as the magnificent bird, with her magical tail feathers trailing behind, brings food to the nest.

A palette of purples, blues, and aqua greens, complemented by shimmering gold, creates a sense of vibrancy, while the sinuous lines of the simurgh‘s tail and the swaying foliage further heighten the drama of Zal’s discovery. Even the rocks seem to pulsate with life as finely drawn animals, grotesques, and human faces emerge from the deep crags.

Image 6 of 15

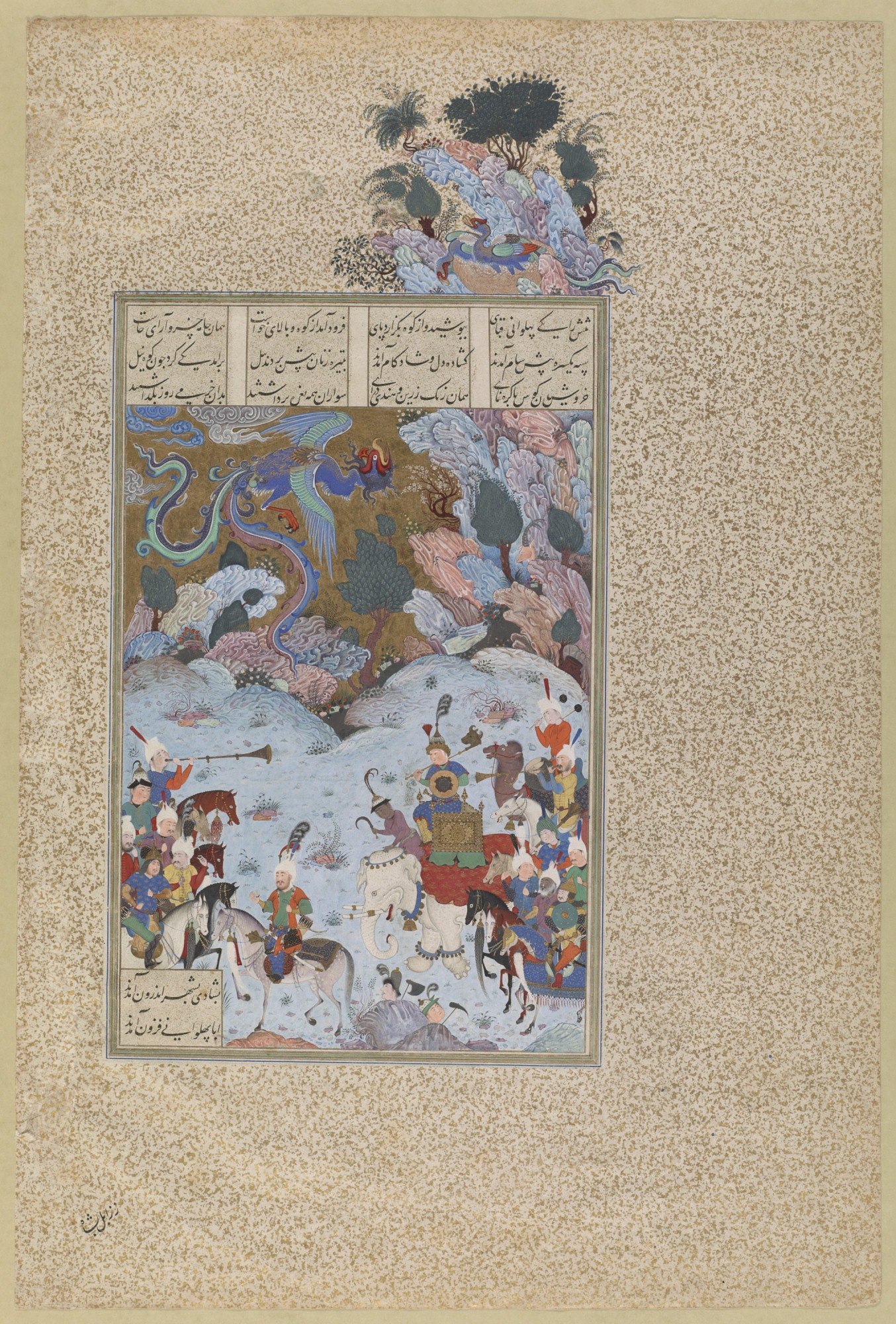

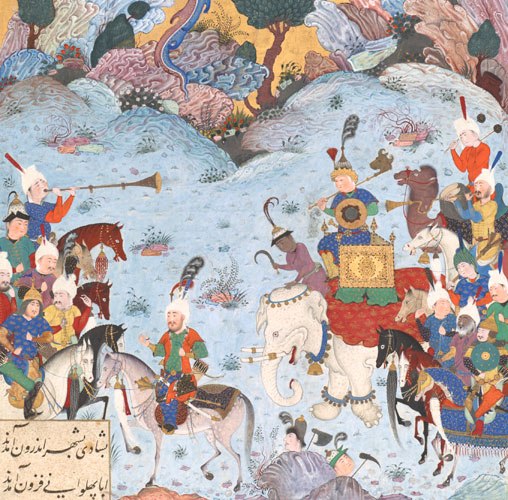

Sam Returns with His Son Zal

Iran, Tabriz, Safavid period, ca. 1520s

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Lent by the Ebrahimi Family Collection

The discovery of the abandoned child Zal and his glorious return to court must have had particular resonance for Shah Tahmasp, for it is illustrated three times by different painters in his personal copy of the Shahnama. Two of the folios were reunited for the first time in decades in the exhibition Shahnama: 1000 Years of the Persian Book of Kings.

Once news reached the royal court that Zal is alive and well, the overjoyed king sets out to find his albino son. At first, Zal is reluctant to leave the only home he has ever known, but the simurgh convinces him to go with his father Sam. The magical creature gives Zal two of her feathers to burn whenever he needs her help. Now dressed in sumptuous Safavid royal robes and seated on a white elephant, Zal is ready to “go and see what fate has in store” for him. As he rides away, accompanied by his proud father and his royal retinue, the simurgh looks up poignantly at her two remaining fledglings in the nest.

Retaining the overall composition of Zal is Sighted by a Caravan, the second artist placed the phoenix’s rocky perch on the right and transformed the boulders into spongelike waves that reach beyond the upper margin. The fantastically rendered landscape also contains ghostlike humans and grotesques that underscore the emotional intensity of the moment.

Image 7 of 15

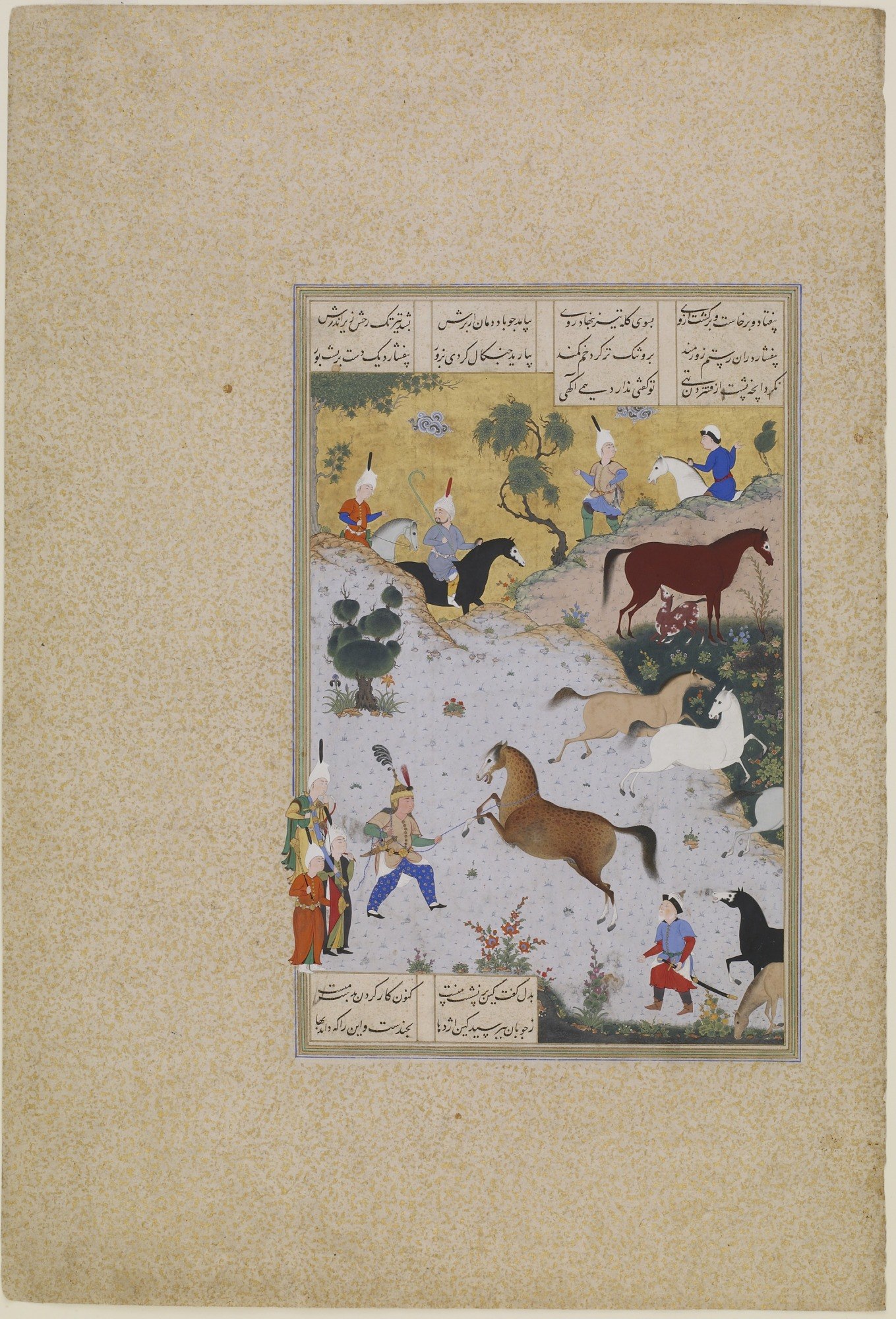

Rustam Lassos Rakhsh

Attributed to Mir Musavvir

Iran, Tabriz, Safavid period, ca. 1525

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Lent by the Art and History Collection LTS1995.2.47

Rustam stands out as the most celebrated and complex character in the Shahnama. He is the son of Zal, an albino nobleman, and Sudaba, a descendant of the villainous Zahhak, which in part accounts for the darker side of his personality. Known for his extraordinary strength, bravery, and loyalty, Rustam is a negahban, a protector of the country’s monarchy. He steadfastly assists less courageous kings against their enemies, especially the Turanians to the east. To this day, Rustam is considered Iran’s greatest folk hero.

As the ultimate champion, Rustam was determined to find a horse to match his own strength and stamina. After several days of searching, he spots a young colt “strong as an elephant…his hoofs of steel, his skin bright and dappled as though flecked with petals of red roses on saffron.” This finely conceived illustration from Shah Tahmasp’s copy of the Shahnama depicts the moment when Rustam subdues the colt Rakhsh (Thunder), a name as well known in Persian literature as that of Rustam himself.

Image 8 of 15

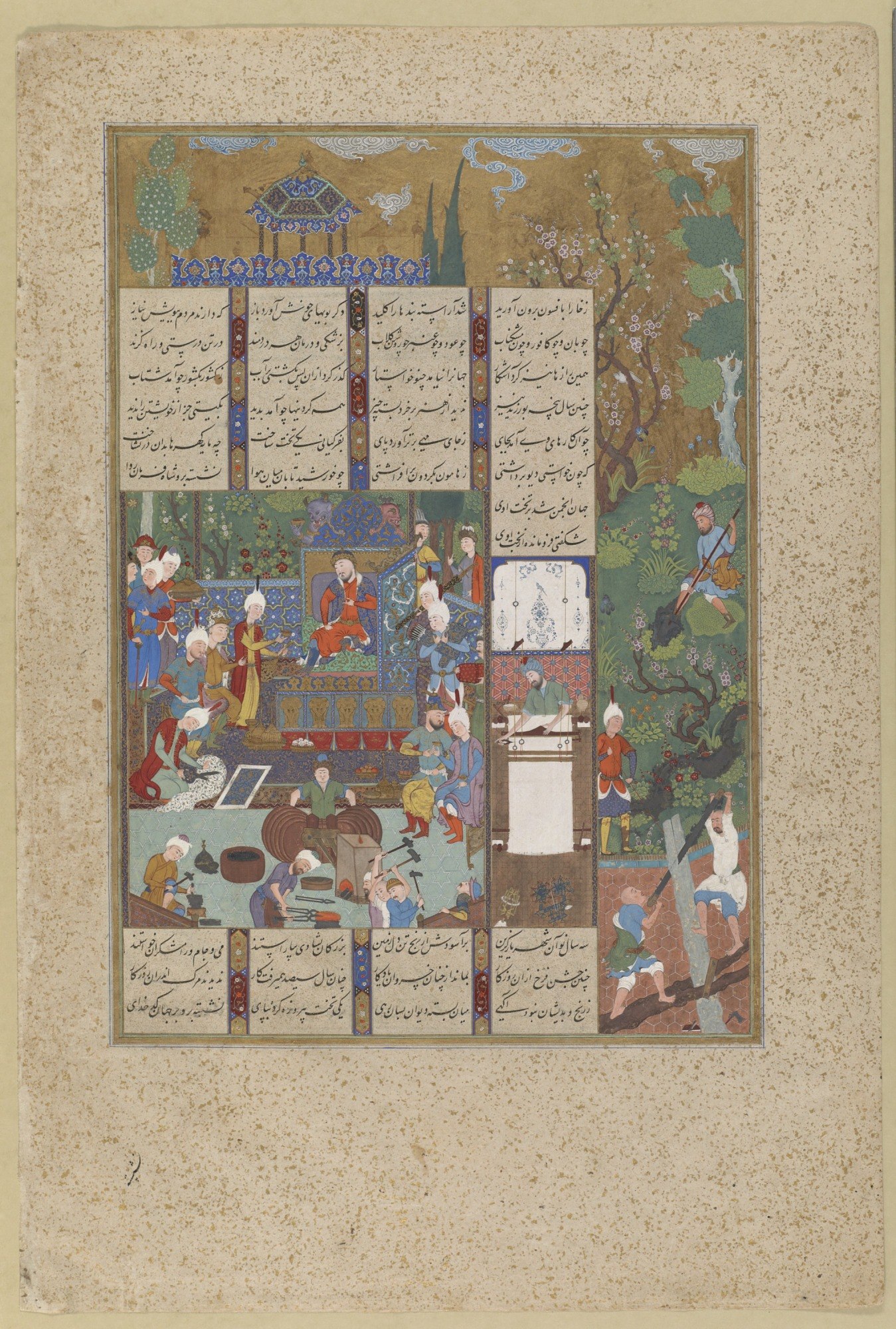

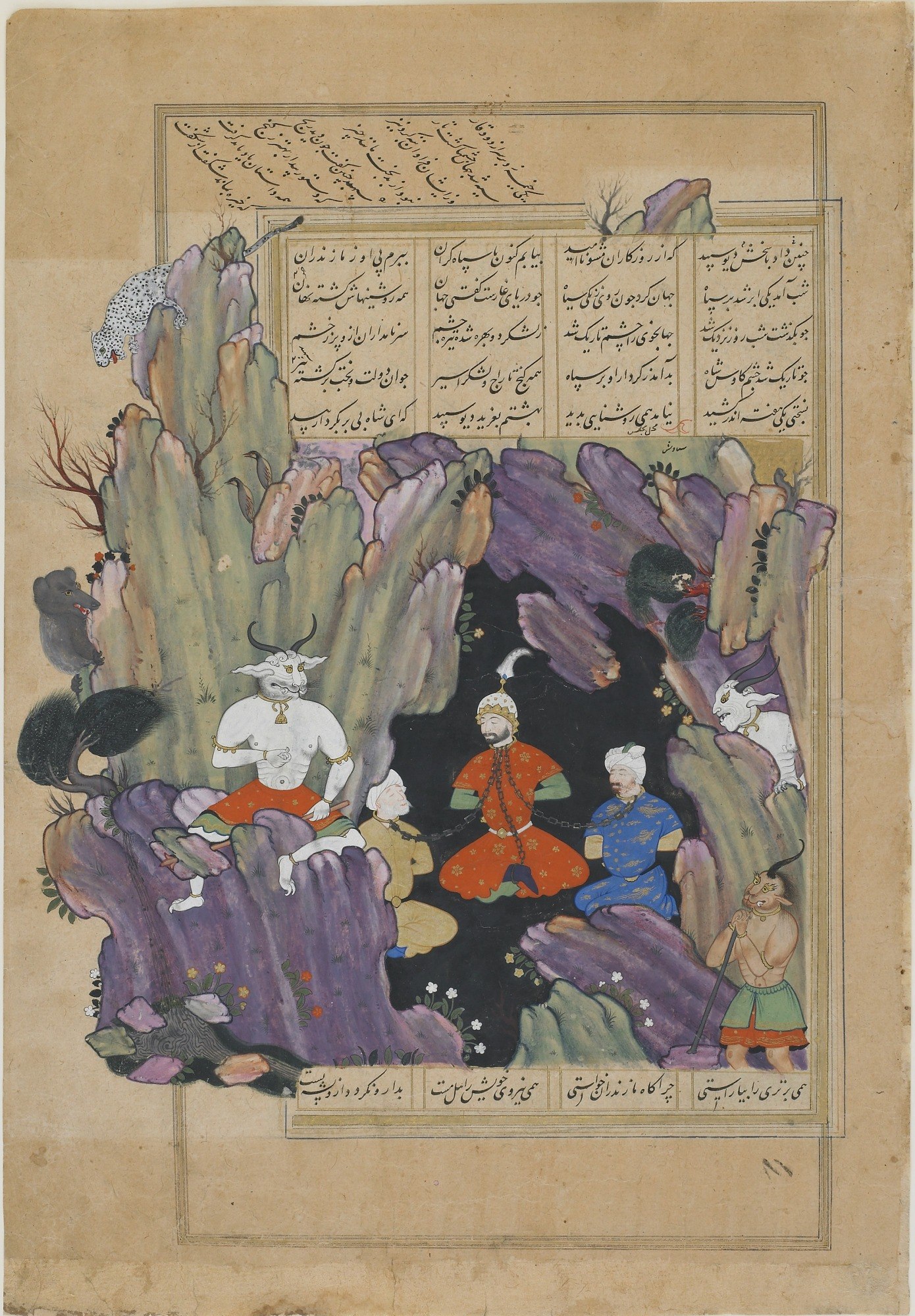

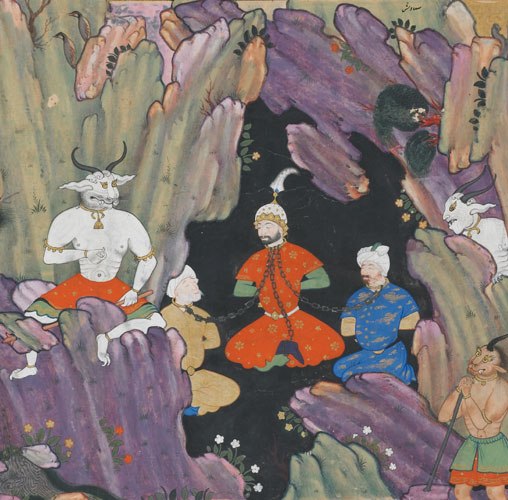

Kay-Kavus Chained in a Cave

Ascribed to Siyavush

Iran, Qazvin, Safavid period, 1576-77

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Purchase in appreciation of Mary Wilkie Ebrahimi and her exemplary service to the Galleries as vice chair of the Board of Trustees (2003–2007)

Freer Gallery of Art F2006.7

Reckless pride leads the arrogant king Kay-Kavus into a hopeless and unnecessary military campaign against the demons of Mazandaran. After Kay-Kavus is swiftly defeated, the White Demon (div-i sifid) blinds and enchains the king and his advisors in a dark, bottomless cave. Mighty Rustam arrives and engages in hand-to-hand combat with the White Demon. He then frees Kay-Kavus, who miraculously regains his sight when his eyes are brushed with the White Demon’s blood.

This folio is from a Shahnama once owned by Ismail II, the son and successor of Shah Tahmasp. The rarely depicted scene is ascribed to the court painter Siyavush, who excelled in portraiture. His sensitive rendering of the blinded and now remorseful Kay-Kavus and the gleeful White Demon perched smugly on the rock suggests the artist’s keen power of observation. Even the snarling bear and growling leopard are treated with personality and humor as they witness the boastful king’s predicament.

Image 9 of 15

Afrasiyab’s Night Attack

Copied by Salik b. Sa’id

Iran, Lahijan, Turkoman period, 1493-94

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Lent by the Art and History Collection LTS1995.2.40

The Shahnama‘s mythical section is dominated by the prolonged struggle between Iran and its eastern neighbor Turan. In this illustration, Afrasiyab, Iran’s formidable enemy, organizes a night attack against the Persian forces as revenge for their invasion of Turan. According to Firdawsi, when the soldiers fall asleep after an evening of drinking and merry-making, Afrasiyab’s men seize the opportunity to descend on them “like a black cloud.” Most of the Persians, shown resting under a tent, are surprised in the attack and killed.

Image 10 of 15

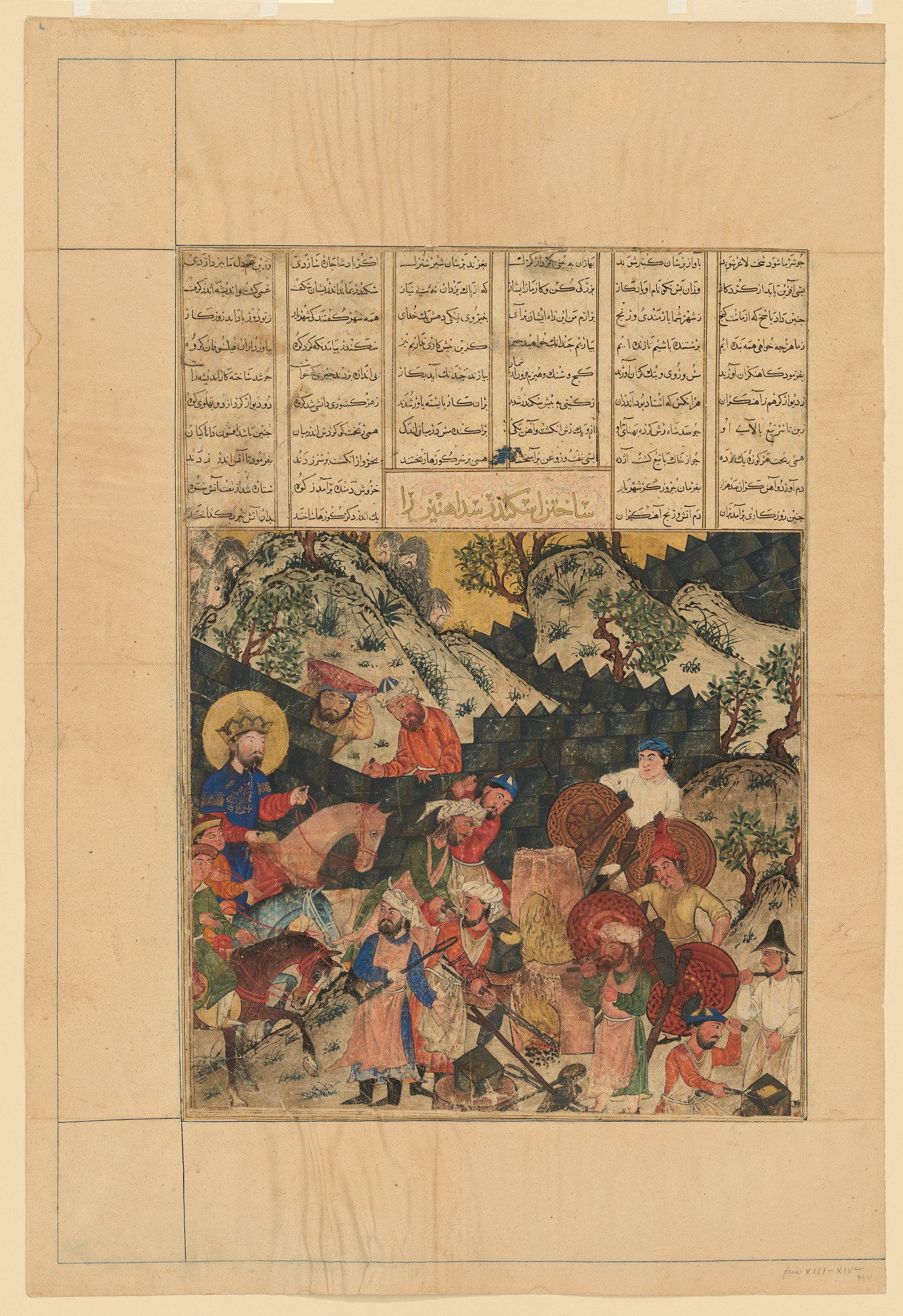

Iskandar Builds the Iron Rampart

Iran, Tabriz, Il-Khanid period, ca. 1330–36

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Purchase—Smithsonian Unrestricted Trust Funds, Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, and Dr. Arthur M. Sackler

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery S1986.104

This illustration depicts one of Iskandar’s best-known adventures at the end of the civilized world, where he encounters the savages of the mythical lands of Gog (Ujuj) and Magog (Majuj). As a just and compassionate leader, Iskandar responds to the desperate pleas of the local population to protect them from the recurring invasions of these marauding people. He gathers workers from all over the world and orders them to construct two walls made of iron, copper, and carbon to keep the evil creatures at bay. In the fourteenth-century illustration, the artist focuses on the active construction of the rampart while the inhabitants of Gog and Magog, whose “faces are that of camels, their tongues are black, and their eyes the color of blood,” watch from behind the hills. Curiously, in the sixteenth-century version of the same scene, which was originally part of Ismail II’s Shahnama, the demonlike creatures help build the very wall that is intended to imprison them.

Image 11 of 15

Iskandar at the Talking Tree

Iran, Tabriz, Il-Khanid period, ca. 1330–36

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Purchase, Freer Gallery of Art F1935.23

When Iskandar reaches the end of the world, he encounters a tree with two trunks. From one trunk sprout male heads that speak during the day in a voice that strikes terror, while the female heads of the other trunk talk sweetly at night. Loudly the male half warns Iskandar that he has already seen his share of blessings and “when he has reigned for fourteen years, he must quit the royal throne.” At midnight the female heads urge him not to give in to greed, which makes one “wander the wide world, harass mankind, and kill kings.” Lastly, they disclose, “Death will come soon: you will die in a strange land, with strangers standing by.”

The artist of this remarkable painting took some liberties with the story. In addition to the male and female faces in the branches, he inserted the heads of a rabbit, a fox, a rooster, and a bird, among other animals. At the base of the tree, fantastically shaped fungi and rocks, inspired by Chinese models, replace the animal bones and skins described in the Shahnama. Their inclusion contributes to the sense of eeriness and foreboding that Iskandar must have felt beneath the tree that predicted his fate.

Image 12 of 15

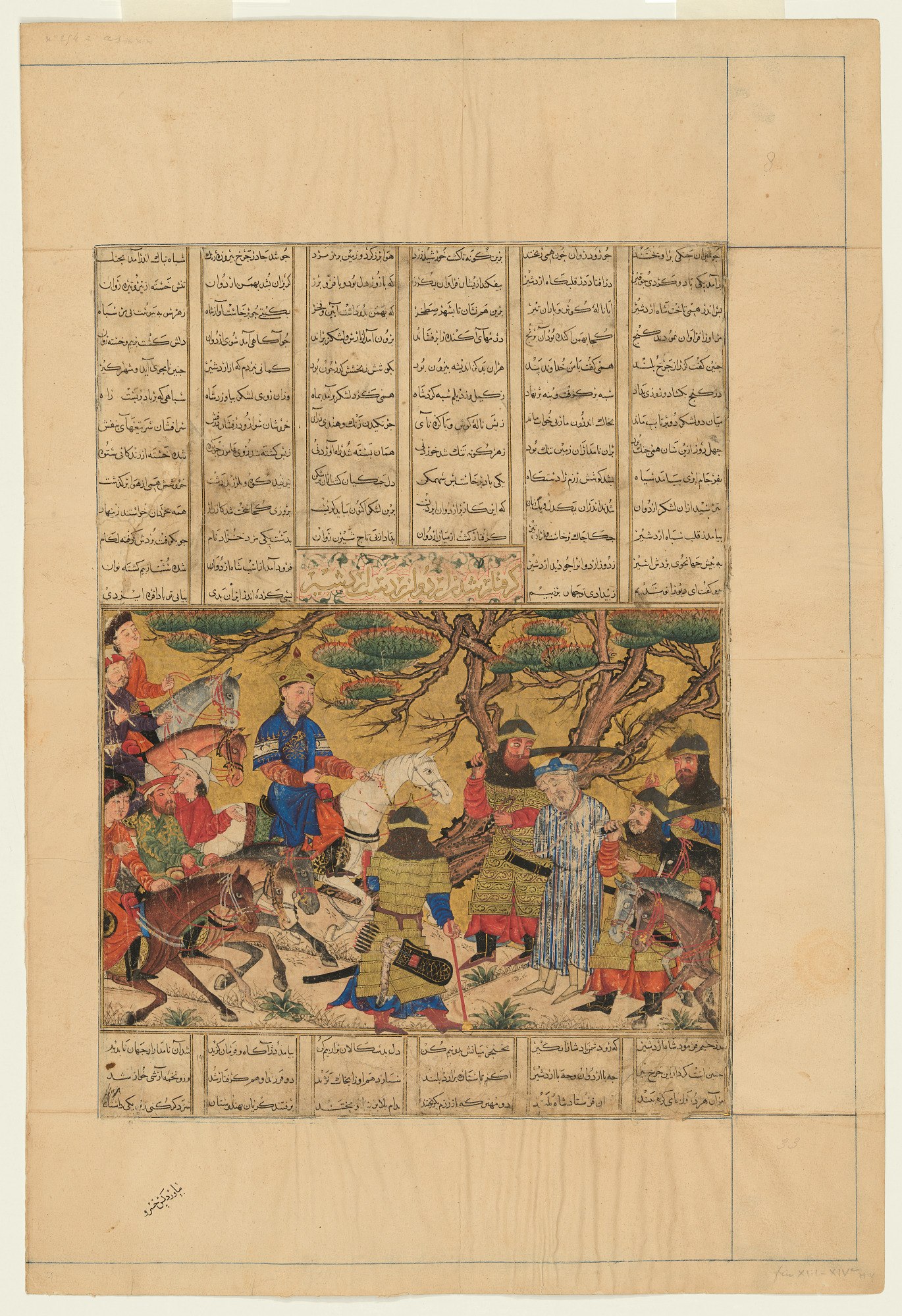

Ardashir Captures Ardavan

Iran, Tabriz, Il-Khanid period, ca. 1330–36

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Purchase—Smithsonian Unrestricted Trust Funds, Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program, and Dr. Arthur M. Sackler

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery S1986.103

Firdawsi’s preoccupation with the concept of justice and the passage of power is central to the story of Ardavan, the last king of the Parthians (247 BCE–224 CE), and Ardashir, the founder of the Sasanian dynasty (224–651). In the epic’s account of the fall of the Parthians, Ardavan invites young Ardashir to live at the royal court, but later in a fit of jealousy the elderly king banishes him to the stables. A series of harsh betrayals leads Ardavan to challenge Ardashir in battle. After forty days of fighting, a wounded and exhausted Ardavan is captured and brought before the ambitious Ardashir and executed.

This scene conveys a deep sense of despair—from Ardavan’s slumped shoulders and downcast eyes to the dry, twisting branches of the tree behind him. By cutting figures off at the margins and placing a central soldier with his back to the viewer, the artist heightens the poignancy of the moment. Such compositional devices were inspired, in part, by Chinese luxury goods that became available in Iran through active land and sea trade in the mid-thirteenth century.

Image 13 of 15

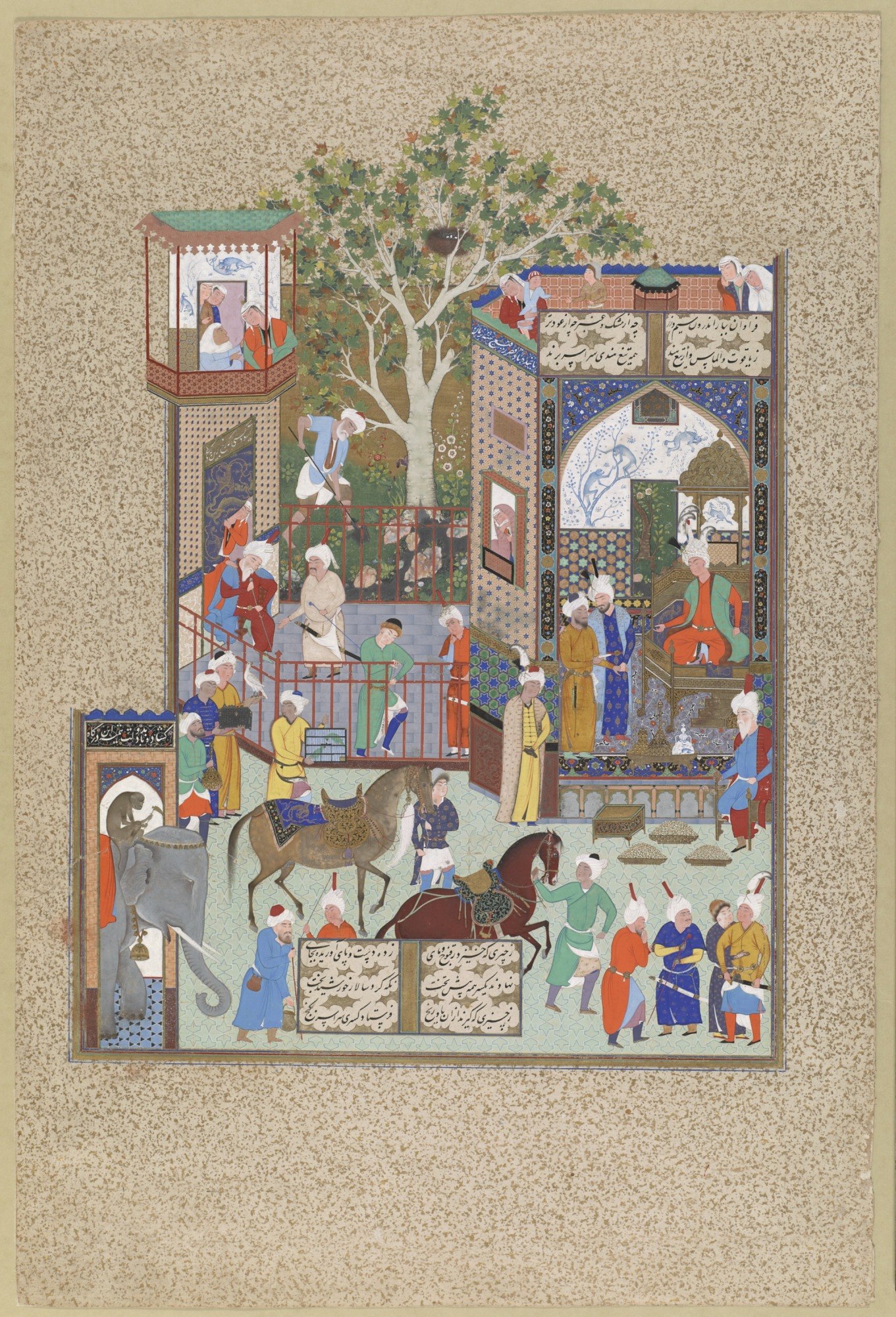

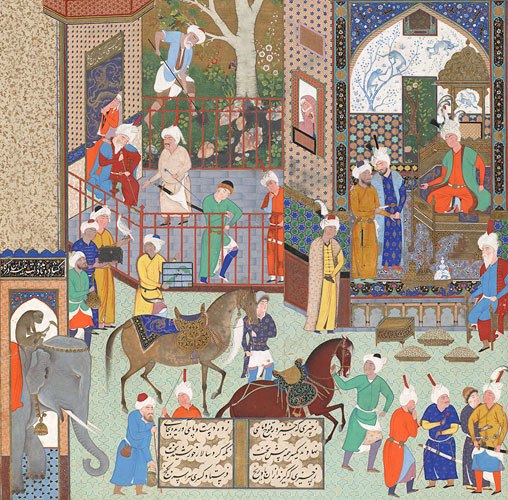

Nushirvan Receives an Embassy from the Raja of Hind

Iran, Tabriz, Safavid period, ca. 1520s

Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

Lent by the Ebrahimi Family Collection

This painting depicts the court of the Sasanian king Nushirvan, who reigned from 531 to 578. Known for his civil and judiciary reforms and fair treatment of his subjects, Nushirvan was commonly known as the “just” (adil). In this carefully balanced but bustling court scene, the king, dressed in Safavid fineries, is enthroned on the right. He addresses the envoy of an Indian raja, who has arrived with a thousand camels laden with sumptuous gifts of gold, silver, rubies, diamonds, and ambergris. Nushirvan and his courtiers are well pleased with the presentation of elegantly saddled horses and ten white elephants, one of which enters the palace gate at the lower left. After these diplomatic gifts are taken to the royal treasury, the envoy offers his most special and mysterious present: the game of chess.

Image 14 of 15

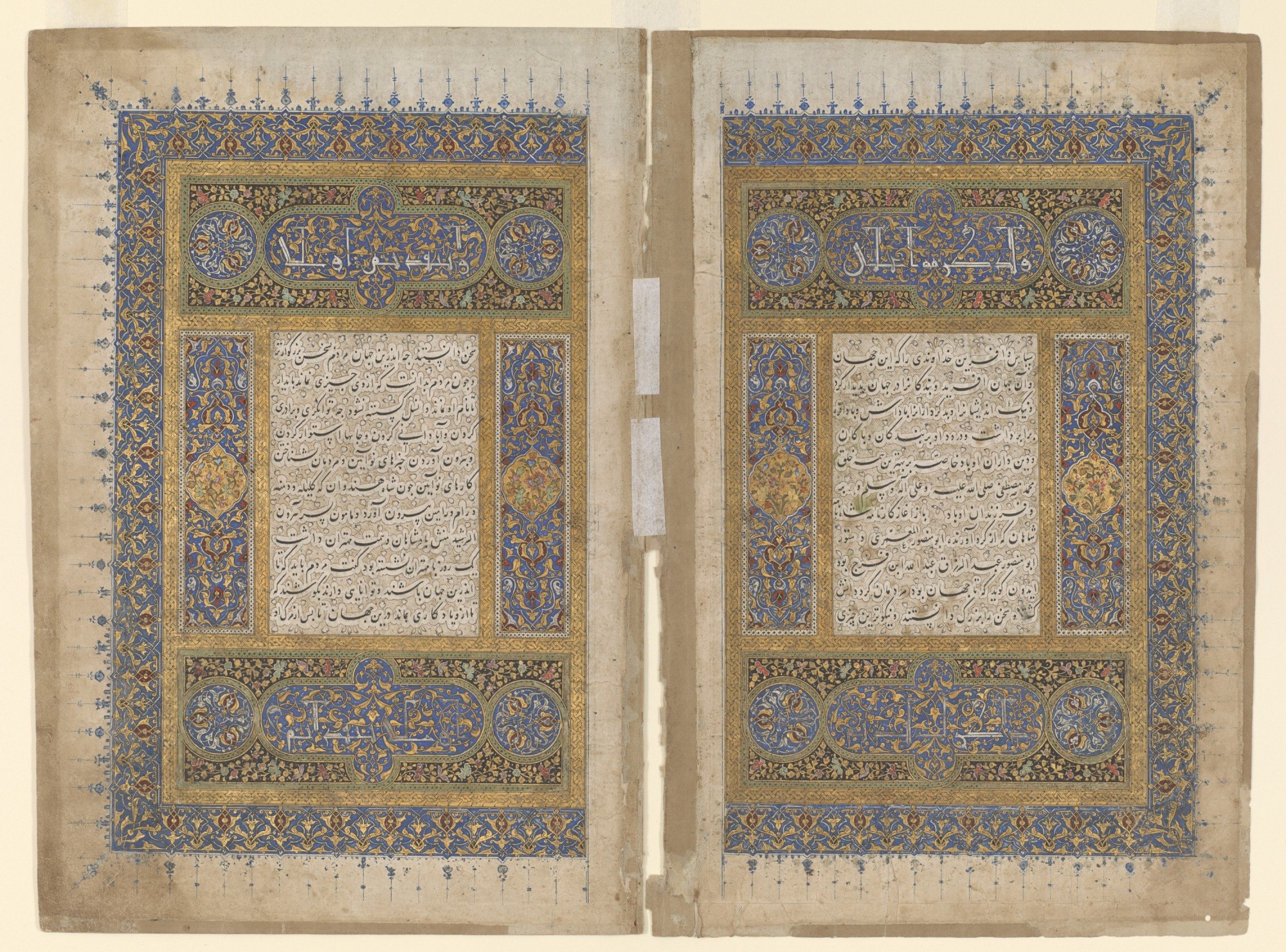

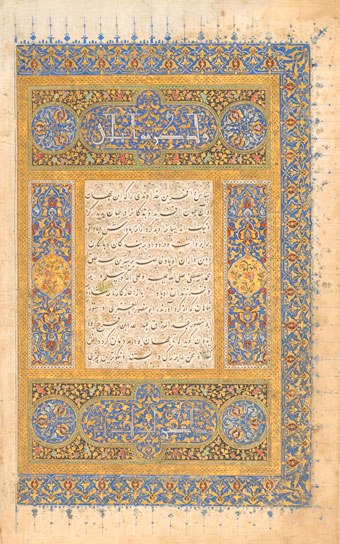

Firdawsi: His Times & Today

Illuminated frontispiece

From a copy of the Shahnama

Copied by Ismail Khaja, son of Mubarak Qadam

Iran, probably Shiraz, dated 1441

Lent by the Art and History Collection LTS1995.2.23

Image 15 of 15

Introduction

One thousand years ago, the Persian poet Firdawsi completed one of the greatest masterpieces of world literature: the Shahnama, or Book of Kings. Composed of some fifty thousand verses, the sweeping epic recounts the myths, legends, and “history” of Iran from the beginning of time to the Arab conquest in the seventh century.

Firdawsi’s text is centered on the reigns of fifty monarchs (including three women) and can be divided into a legendary and a quasi-historical section. It begins with the reign of Kayumars at the dawn of time and concludes with the last Sasanian king, Yazdigird (reigned 632–651), who was defeated by the Arabs. These fifty “chronicles” provide a framework for the dramatic deeds and heroic actions of a range of other personages who are often aided by—or at battle with—a host of fantastic creatures and treacherous villains. The poem draws on a wealth of sources, including local and dynastic histories, the Avesta (the sacred text of the Zoroastrian religion of ancient Iran), and myths and legends preserved in oral tradition.

Over the centuries, foreign conquerors and local rulers alike were drawn to the Shahnama for its emphasis on justice, legitimacy, and especially the concept of divine glory. Known as khavarnah in the Avesta and as farr in modern Persian, divine glory was considered the most important attribute of kingship, for it enabled rulers to govern and command obedience. Not surprisingly, commissioning lavishly illustrated copies of the Shahnama became almost a royal duty. By representing the kings and heroes of the epic according to the style of their own times, members of the ruling elite were able to cast themselves as the legitimate heirs of Iran’s monarchical tradition, which according to Firdawsi dates back to the beginning of time.

Credits

This feature is based on a brochure produced for Shahnama: 1000 Years of the Persian Book of Kings. The exhibition and brochure have been made possible by a generous grant from The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund.

All quotes are taken from Abolqasem Ferdawsi, The Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, translated by Dick Davis (New York: Viking Penguin, 2006).

Additional Reading

For further reading, see Abolqasem Ferdowsi, Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, Stories from the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, translated by Dick Davis and originally published in three volumes: The Lion and the Throne, Fathers and Sons, and Sunset of Empire (Washington, D.C.: Mage Publishers, 1997).

KAYUMARS

According to the Shahnama, Kayumars was the first king of Iran. He and his people lived in the mountains and wore clothes of leopard skins, as is depicted in this early sixteenth-century illustration. He taught mankind how to prepare food and established the ceremonies of kingship. Kayumars’ thirty-year reign was a period of peace and civility, when man and beast coexisted in blissful harmony and all the animals of the world paid homage to him.

HUSHANG

This tranquility was shattered when evil entered the world, and the Black Demon (div-i siyah) killed Kayumars’ handsome son Siamak. Hushang, the son of Siamak and the grandson of King Kayumars, avenged his father’s death by leading an army of “fairies, leopards and lions, savage wolves and fearless tigers” against the Black Demon. “Like a lion, Hushang caught the Black Demon in his grip … laid him low in the dust and flayed his wretched body of its skin.” Satisfied with this vengeance, Kayumars died.

The reign of King Jamshid ushered in the first golden age in Iran’s history. “The imperial farr was his. The world submitted to him, quarrels were laid to rest ….” Jamshid introduced the sciences, arts and crafts, medicine, shipbuilding, mining, and the use of perfumes. He organized society in accordance with the professional classes, and he established Now-ruz (New Day) on the first of Farvardin (21 March), when he finally rested from his endeavors. For three hundred years Jamshid ruled over a country where “men knew nothing of sorrow or evil … and the land was filled with music,” but he became increasingly arrogant with his achievements.

Jamshid surveyed the world, and saw none there

Whose greatness or whose splendor could compare

With his: and he who had known God became

Ungrateful, proud, forgetful of God’s name.

Such hubris cost him divine glory (farr), the most important attribute of kingship. Iran was soon filled with dissension and revolt, and the once-glorious Jamshid went into hiding for a hundred years. When he reappeared on the shores of the Sea of China, he was killed by the demon-king Zahhak.

The tyrannical Zahhak reigned for a thousand years, and from end to end the world was his to command. The wise concealed themselves and their deeds, and devils achieved their heart’s desire. Virtue was despised and magic applauded, justice hid itself away while evil flourished; demons rejoiced in their wickedness, while goodness was spoken of only in secret.” Zahhak dreams of the yet-unborn Faraydun who will one day defeat him and bring his reign of darkness to an end. Obsessed with finding and killing Faraydun, Zahhak gathers great men from every country and asks for their support in raising an army.

Neither the throne nor good fortune will remain with one man forever…. I have come from Persia bringing war, and I shall give the evil Zahhak no rest or peace until I have crushed his head beneath my ox-headed mace.

As predicted in Zahhak‘s dream, the noble Faraydun was born and “grew as straight as a tall cypress tree and … imperial farr radiated from him as if he were the sun.” He pursues the evil king to end his reign and free the world of tyranny. When he arrives at Zahhak’s deserted palace, Faraydun releases King Jamshid’s imprisoned sisters, who have been bewitched by Zahhak’s magic, and then places himself on the throne. News of his overthrow reaches Zahhak, and the enraged sorcerer-king rushes back from India to kill Faraydun himself.

Disguised in iron armor, the king sneaks into the palace, intent on shedding blood. “As Zahhak’s foot touched the ground, Faraydun leapt forward like the wind and brought his ox-headed mace crashing down on Zahhak’s head, so that his helmet was shattered.” Faraydun is about to deliver a second—and fatal—blow when the angel Surush appears and proclaims, “His time has not yet come.” Surush orders Faraydun to put Zahhak in chains and take him to Mount Damavand, where “this solitary wretched captive” will perish alone in a deep cave.

Zal, the father of the hero Rustam, is born with a “face like paradise, … but his hair was that of an old man.” Born an albino, his snow-white hair is considered an ill omen. His father, Sam, ashamed of the newborn’s strange appearance, orders Zal to be left in the mountains where the mythical simurgh makes her home. When the phoenix flies from her nest in search of food for her fledglings, she takes pity on the infant and raises him as her own.

One day, a passing caravan catches sight of the noble youth, “whose body was like a cypress tree, whose chest was like a mountain of silver, and whose waist was as slim as a reed.” News of the event reaches Sam, who deeply regrets abandoning his son. Sam and his retinue arrive to find young Zal perched on a mountain peak. At first Zal is reluctant to leave the only home he has ever known, but the magical bird convinces him to go with his father. The phoenix hardens her heart for their parting and gives Zal two of her feathers to burn whenever he needs her help. She urges Zal to “go and see what fate has in store” for him.

Rustam, the son of Zal, stands out as the most celebrated and complex character in the Shahnama, and to this day he is considered Iran’s greatest folk hero. Known for his extraordinary strength, bravery, and loyalty, Rustam is a negahban, a protector of Iran’s monarchy. He steadfastly assists weaker and less courageous kings against their enemies, particularly the people of Turan to the east.

As the ultimate champion, Rustam is determined to find a horse to match his own strength and stamina. After several days of searching, he spots a young colt “strong as an elephant … his hoofs of steel, his skin bright and dappled as though flecked with petals of red roses on saffron.” Rustam subdues the colt by throwing a lasso around its neck. When he asks for the horse’s price, the herdsman replies, “If you are Rustam, then mount him and defend the land of Iran. The price of this horse is Iran itself, and mounted on his back you will be the world’s savior.” He calls it Rakhsh (Thunder), a name as well known in Persian literature as that of Rustam himself.

Rakhsh’s intelligence and devotion become particularly apparent during the first of seven ordeals or heroic labors that occur when Rustam must rescue the foolhardy and impetuous king Kay-Kavus, who had been imprisoned by the White Demon in far-off Mazandaran. Overcome by fatigue on his long journey, Rustam lies down to rest. When a ferocious lion threatens to attack, Rakhsh, “boiling like water,” seizes the beast by its neck and kills it without disturbing the sleeping Rustam.

Reckless pride leads the arrogant king Kay-Kavus into a hopeless and unnecessary military campaign against the demons of Mazandaran. After Kay-Kavus and his armies are swiftly defeated, the White Demon (div-i sifid) blinds and enchains the king and his generals in a secluded cave. The White Demon roars:

“Kavus, you’re like a willow, fruitless and afraid.

And you once thought your army could invade

Mazandaran, and that your strength is like

A maddened mammoth’s when you choose to strike!

Since you have occupied the Persian throne,

Wisdom’s deserted you, good sense has flown.

Here is the end of everything you sought,

Here is the punishment for which you fought!”

The mighty Rustam arrives in Mazandaran and engages in hand-to-hand combat with the White Demon, “the two locked together like an elephant and a lion.” Victorious, Rustam frees Kay-Kavus, who miraculously regains his sight when his eyes are brushed with the White Demon’s blood.

Year after year Iran and its eastern neighbor Turan battle for supremacy over the region. Afrasiyab, Iran’s formidable enemy, organizes a night attack against the Persian forces as revenge for Iran’s invasion of Turan. When the Persians fall asleep after an evening of drinking and merry-making, Afrasiyab’s men descend on them “like a black cloud.” Most of the soldiers, sleeping under a tent, are surprised in the night attack and killed.

Iskandar (Alexander, the Macedonian conqueror) ushers in the quasi-historical section of the Shahnama. Firdawsi justifies Iskandar’s claim to the Persian throne by maintaining he was the son of Darab (Darius II), who married the daughter of Philip of Macedonia. When his half-brother Dara (Darius III) is murdered, Iskandar promises to protect and rule over Iran in his place.

Following his accession to the Persian throne, Iskandar sets out in search of knowledge and wisdom, a quest that takes him on fantastic adventures to known places and mythical lands. In his travels, Iskandar confronts and defeats his enemies, learns from different cultures, and dispenses justice, as he does with Taynush, the son of Qaydafa, the wise queen of Andalus. Seated beneath a blossoming tree and surrounded by his noblemen, Iskandar calmly addresses the impetuous Taynush, who agrees to abandon his plans to avenge the death of his father-in-law Fur, a ruler of India (whom Iskandar had killed). The king reassures Taynush that he is safe.

“I shall not break my word to Qaydafa—

My promise will be kept in every way:

There is no good in lying kings who make

Fair promises they then proceed to break.”

Next, Iskandar leads his army to the land of the Brahmans, where he hopes to learn their ancient practices. He “heard their chants, and saw them running with naked feet, bodies, and heads; he saw that their bodies were unprovided for but their souls were filled with the fruits of knowledge.” Iskandar questions the ascetics on life and death and their peace in the midst of war. They reply: “An ambitious man struggles to gain something that is not worth the effort he has put forth, and then he passes from the world while his gold and treasure and crown remain here. Only his good deeds will accompany him, and his head and glory will both return to dust.” They warn Iskandar of the dangers of greed and excessive pride in trying to conquer the world, and they also remind the conqueror of his mortality before he heads into unknown lands to the east.

At the end of the civilized world, Iskandar encounters the savages of the mountainous land of Gog and Magog. As a just and compassionate leader, he responds to the desperate pleas of the local population to protect them from the recurring invasions of these marauding people, whose “faces are that of camels, their tongues are black, and their eyes the color of blood.” Iskandar gathers masons, blacksmiths, and craftsmen from throughout the world and orders them to construct two massive walls to keep the evil creatures at bay. “The earth was once again a place of peace and pleasure: the famous barrier of Iskandar had delivered the world from strife.”

When Iskandar reaches the end of the world, he encounters a tree with two trunks. From one trunk sprout male heads that speak during the day in a voice that strikes terror, while the female heads of the other trunk talk sweetly at night. Loudly the male half warns Iskandar that he has already seen his share of blessings and “when he has reigned for fourteen years, he must quit the royal throne.” At midnight the female heads urge him not to give in to greed, which makes one “wander the wide world, harass mankind, and kill kings.” Lastly, they predict:

Neither your mother, nor your family,

Nor the veiled women of your land will see

Your face again. Death will come soon: you will die

In a strange land, with strangers standing by.

As the talking tree prophesied, Iskandar died in Babylon far from his home. His coffin, made of solid gold, was carried to Alexandria, Egypt, where it was placed in the midst of a wide plain and thousands of his followers came to mourn. “The philosopher Aristotle was there, his eyes filled with bitter tears; the world watched as he stretched out his hand to the coffin and said, ‘Where are your intelligence, knowledge, and foresight, now that a narrow coffin is your resting place?’ … And then his mother came running, and placed her face on this chest, and said,

“O noble king, world-conqueror, whose state

Was princely, and whose stars were fortunate,

You’re far away from me and seem so near,

Far from your kin, far from your soldiers here.”

To conclude the story of Iskandar, Firdawsi addresses the reader. “There is nothing in the world so terrible and fearful as the fact that one comes like the wind and departs as a breath. … Whether you are a king or a pauper you will discover no rhyme or reason to it. But one must act well, with valor and chivalry, and one must eat well and rejoice: I see no other fate for you, whether you are a subject or a prince.”

The passage of power from one generation to the next is central to the story of Ardavan, the last Parthian king, and Ardashir, the founder of the Sasanian dynasty. When Ardavan hears of young Ardashir, “who was said to be a raging lion in battle” and gracious at banquets, the elderly king invites him to the royal court. One day Ardashir’s superior hunting skill so angers Ardavan that he banishes the handsome youth to work in the stables. Even in this lowly position, Ardashir attracts the love of the beautiful slave girl Golnar, who is trusted with the treasury of Ardavan. Golnar steals gold and jewels from the devoted king and flees with the charismatic Ardashir. Betrayed and humiliated, Ardavan challenges Ardashir to battle. After forty days of fighting, Ardavan is taken prisoner. The gray-haired king, wounded and exhausted, is brought before the ambitious Ardashir and executed.

The ancient heavens turn; kings disappear,

Now Ardavan is gone, now Ardashir,

And though their heads reach to the stars they must

At last be humbled in the lowly dust.

Nushirvan was known for his righteous rule and fair treatment of his subjects. He graciously welcomes the envoy of an Indian raja, who arrived with a thousand camels laden with sumptuous gifts of gold, silver, rubies, diamonds, and ambergris. Nushirvan and his courtiers are well pleased with the presentation of elegantly saddled horses and ten white elephants. After these diplomatic gifts are taken to the royal treasury, the envoy offers his most special and mysterious present: the game of chess.

Very little is known about the poet Abul-Qasim Firdawsi, not even his real name. Since Firdawsi means “paradisal,” this must have been his poetic or pen name. Born around the year 940 into a family of landed nobility (dihqans) in Tus, near the city of Mashhad in northeastern Iran, Firdawsi began composing his epic shortly after 975, at a time when eastern Iran had become increasingly independent of the Abbasid dynasty (reigned 750–1258) centered in Baghdad. Of the many local dynasties that gained control in the east, the Samanids (reigned 819–1005) ushered in one of the most brilliant periods in the cultural history of Iran. Proud of their Persian heritage, the Samanids actively encouraged a renaissance of Persian literature, poetry, and culture, and at their royal court and its capital Bukhara, in present-day Uzbekistan, they supplemented Arabic learning with the Persian language. The single most important manifestation of this renewed pride in Persian culture was the Shahnama, a celebration of Iran’s pre-Islamic past.

By the time Firdawsi completed his epic poem in 1010, the Samanids had been overthrown by the Ghaznavids (reigned 977–1186), a Turkic dynasty from Central Asia, and the brief Persian renaissance came to an abrupt end. According to legend, when Firdawsi delivered his epic to the Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud (died 1030), the sultan insulted the poet by paying him a meager fee, which Firdawsi shared with a bath attendant and a beer seller before he returned to his native Tus. Ten years later, Sultan Mahmud regretted the slight and sent camels loaded with precious indigo to Firdawsi. When the caravan entered Tus, it encountered a funeral procession accompanying Firdawsi’s coffin. As the poet predicted, however, over time the Shahnama achieved unrivaled status and is considered the most potent expression of Persian literary and national identity to this day.

By focusing on the lives of kings, heroes, and villains and in particular on the moral consequences of their deeds and actions, Firdawsi touches on concerns and dilemmas that continue to plague and intrigue to this day: the struggle between good and evil; the proper actions of a leader; the meaning of truth, integrity, and loyalty. Even though Firdawsi wrote the Shahnama a millennium ago, many of the epic’s characters and themes still seem familiar today. The battle between young Faraydun and the evil sorcerer-king Zahhak has echoes in Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader of Star Wars fame. The fantastic simurgh, with its magical tail feathers, could come straight from a Harry Potter book, and the exciting adventures of Rustam bring to mind the larger-than-life stories of Superman, Batman, and a score of other comic book heroes.

Over the centuries, the value and significance of these stories have only increased as they continue to delight, intrigue, and counsel new readers. Just as it did a thousand years ago, the Shahnama still offers insight into the wisdom and folly of human nature.

I’ve reached the end of this great history

And all the land will fill with talk of me

I shall not die, these seeds I’ve sown will save

My name and reputation from the grave,

And men of sense and wisdom will proclaim,

When I have gone, my praises and my fame.

— Firdawsi

Kay Ka’us chained in a grotto by the white demon, from a Shahnama (Book of kings) by Firdawsi F2006.7

- Jump To...