Charles Lang Freer’s Art Vouchers

In 1893, Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919) began implementing the voucher system, an accounts-payable process developed in the late nineteenth century that was widely adopted by large corporations, to manage purchases of artworks and other expenses related to his renowned collection of Asian and American art. As a former accountant for the New York, Kingston, and Syracuse Railroad Company and then an owner and executive of the Peninsular Car Company, Freer had experience managing finances, so it comes as no surprise that he maintained impeccable financial records for his collection. The voucher system allowed Freer, the litany of clerks affiliated with the banks he patronized, and his private accountants to track his many purchases from the moment the collector identified something to buy to the moment vendors debited his accounts. Today, these records are preserved in the National Museum of Asian Art Archives and allow researchers to study not only Freer’s personal collecting practices but also several other facets of art history and daily life at the turn of the century.

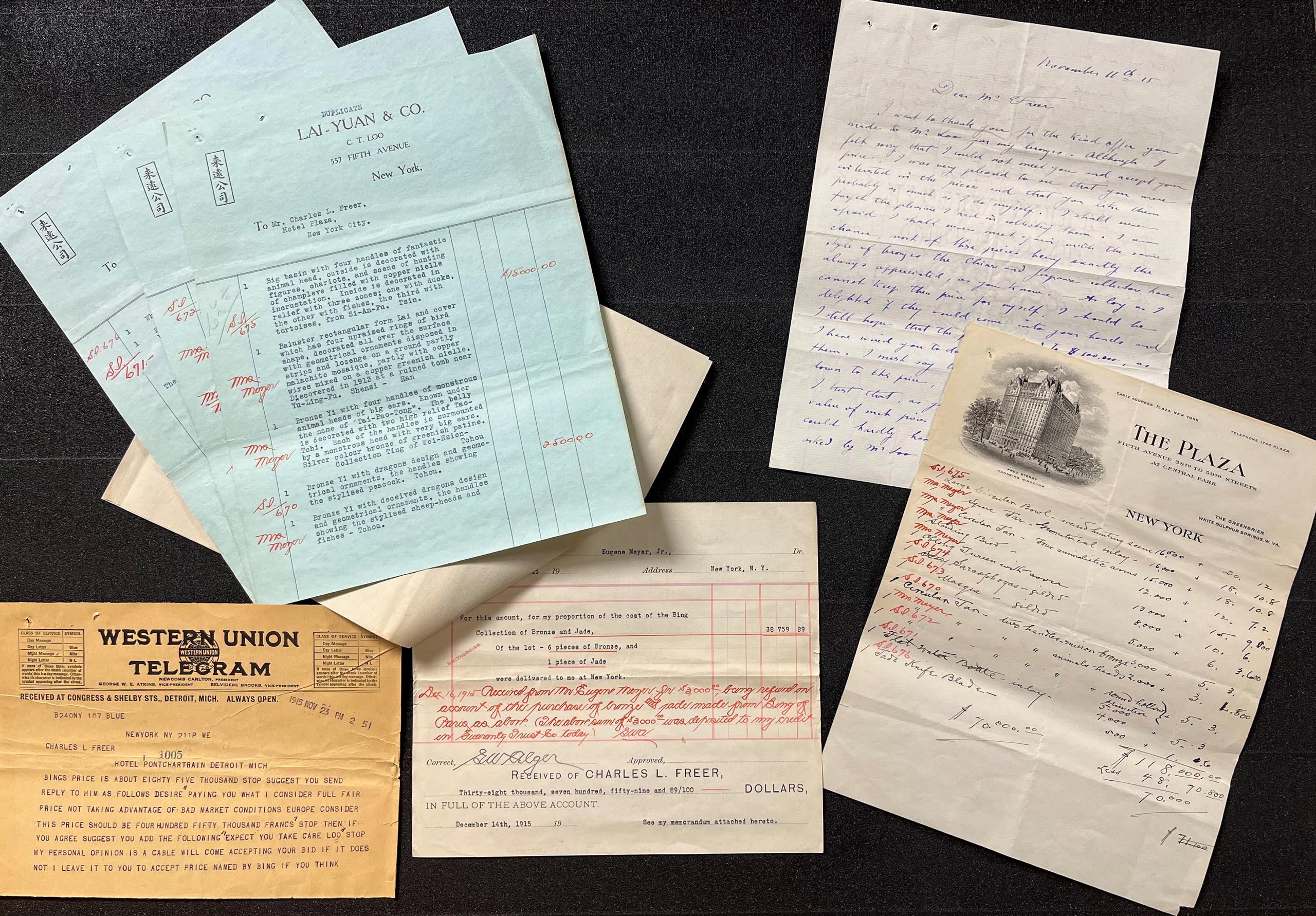

A voucher is a document that confirms a business transaction is truthful. The voucher system uses individual records to organize outgoing expenses, grouping all documents related to a singular purchase and indexing the information found on those documents. Freer’s vouchers, measuring roughly seven-by-eight inches, were designed to fold in half to contain purchasing paperwork, including correspondence from dealers and other vendors, provenance documentation, photographs, publications related to works of art, and invoices. Emblazoned with “C. L. Freer” in bold lettering, each voucher provided a place for the accountant to record the purchase price and month of purchase and to describe the transaction. The accountant would also record the date of payment and the corresponding check number and note where one could locate the debit recorded in Freer’s central voucher registration book in which all outgoing payments were recorded.

Accountants would track the progress of a purchase on the interior of the voucher. After recording the arrival date of the invoice and itemizing the proposed purchase, the accountant signed in approval and then presented the voucher and its accompanying paperwork to Freer. It seems that at this stage Freer annotated the voucher and its contents, identifying where he wanted objects to go: his home, to a friend, or, after 1903, directly to the Smithsonian Institution. Upon Freer’s approval, accountants issued a check, which they sent to the vendor along with the voucher itself. Upon deposit, the vendor signed, dated, and returned the voucher to Freer’s home in Detroit, where clerks filed it for reference.1

While the vouchers themselves offer great insight into financial practices at the turn of the century, the documents that accompany them are vital to understanding the global art market at the time. Freer made purchases from dealers, fellow collectors, and artists in America, Europe, and Asia whom he met during his travels. When Freer’s health began to fail in the early 1900s, vendors frequently sent large crates of artworks to his Detroit home, allowing him to select wares comfortably and at a leisurely pace. Dealers often sent Freer more than he requested for purchase, hoping something else would catch the famed collector’s eye. Through the voucher documents, researchers can reconstruct an object’s journey across the globe and discover the histories of not only the objects that Freer acquired but also those he turned down. Freer routinely annotated the invoices and letters that were filed with the final vouchers, noting which works to gift to friends, striking through objects to return, and listing features of certain objects that appealed to him. Researchers can explore how Freer negotiated prices, demonstrated a preference for particular types of works, and developed his ideas about taste and aesthetics. For example, the annotations on a November 26, 1904, invoice from Yamanaka & Company highlight Freer’s fascination with color and saturation. Next to the dealer’s object descriptions, Freer noted the “brilliant colors” in a kakemono (F1904.340a–h) and “the chocolate-colored glaze with an overflow of dark brownish red and orange” on an Edo-period rooster ewer (F1904.331a–b).2

Freer’s voucher collection provides a sense of how World War I (1914–18) shifted the art market from Paris to New York. European dealers and collectors hurriedly sold collections for lower prices as sales were increasingly directed through New York galleries, where Americans were enthusiastically buying. For example, the documentation created in 1915 for a collection of important Chinese bronzes and a jade (F1915.102, F1915.103a–b, F1915.104, F1915.105, F1915.106a–f, F1915.107, F1915.108, F1961.30a–b, F1961.31a–b, F1961.32a–b, F1968.28 and F1968.29) from the jeweler and art dealer Marcel Bing (1875–1920), brokered by C. T. Loo (1880–1957) through his New York gallery, Lai-Yuen & Co., illustrates this market shift and highlights the American economic advantage. In a letter to Freer explaining his refusal to further discount the bronzes, Bing laments that “[he] should not desire [to] come down to this [previously identified] price, had circumstances been as usual.”3 The war’s impact on global economics led the value of the United States dollar to skyrocket and presented Americans with an opportunity to compete with European elites more boldly in the purchase of fine art. Freer and his friends and fellow collectors Eugene and Agnes Meyer (1875–1959; 1887–1970), with whom he purchased the group of bronzes, therefore secured the works for a competitive price by paying in francs.4

The vouchers and documents also provide an opportunity to trace the evolution of how the West studied Asian works of art. Correspondence pertaining to acquisitions between Freer, the dealer Bunkio Matsuki (1867–1940), and the intellectuals Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) and Edward S. Morse (1838–1925) reveal how the early study of Chinese and Japanese ceramics depended upon art historical comparisons of objects. Dealer invoices and letters contain words and phrases used to identify types of glazes, painting techniques, and bronze patinas and illustrate how those classifications evolved. Freer often sought works of art by named artists. The correspondence and annotations on dealer invoices reflect his desire to know details about craftsmen and his growing knowledge of the works in his collection as well as improvements in his ability to identify styles and artists.

When Freer began to consider giving his collection to the Smithsonian Institution around 1902, he and his accountants retroactively applied the voucher system to his earlier art purchases, thereby organizing all acquisition information for nearly his entire collection.5 It is unclear what exactly drove this decision; however, it is clear that Freer saw this resource as indispensable information. Before his death, Freer reserved all the vouchers and the documents they enclosed for transfer to the Smithsonian, where they have been located since 1920. Freer and his contemporaries surely understood the materials’ practical importance in transferring ownership of the collection, but did the group also have the foresight to consider them invaluable assets for future scholars? Indeed, this trove of primary sources proves significant to advancing knowledge of not only the history of Charles Lang Freer’s renowned collection but also financial management, the global art market in the early twentieth century, histories of collecting and taste, and the understanding of Asian art in the West.