February 26, 2011–July 31, 2011

-

Dates

-

Location

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

-

Collection Area

Chinese Art

Majestic sixth-century Chinese Buddhist sculpture is combined with 3-D imaging technology in this exploration of one of the most important groups of Buddhist devotional sites in early medieval China. Carved into the mountains of northern China, the Buddhist cave temples of Xiangtangshan (響堂山, pronounced “shahng-tahng-shahn”) were the crowning cultural achievement of the Northern Qi dynasty (550–77 CE). Once home to a magnificent array of sculptures—monumental Buddhas, divine attendant figures, and crouching monsters framed by floral motifs—the limestone caves were severely damaged in the first half of the twentieth century, when their contents were chiseled away and offered for sale on the international art market.

In Echoes of the Past, ancient sculptural masterpieces are united with a set of innovative digital components, including a video installation that offers an immersive, kinetic re-creation of one of the largest stone temples. Touch screens and research kiosks offer more detailed information about the site and the themes explored in the exhibition.

Carved into the mountains of northern China, the Buddhist cave temples of Xiangtangshan (“Shahng-tahng-shahn”) were the crowning cultural achievement of the Northern Qi (“Chee”) dynasty (550-77). The name Xiangtangshan translates to “Mountain of Echoing Halls.” It refers to two groups of caves: northern Xiangtangshan and southern Xiangtangshan, located about nine miles apart in Hebei province.

Commissioned by devout Buddhist emperors and courtiers, the manmade caves represent the power and prestige of the throne and an eternal appeal for divine protection. They also reflect a long tradition, begun in India, of situating holy places within the earth’s mantle.

Once home to a magnificent array of sculptures, the limestone caves were severely damaged in the early twentieth century when much of their contents were chiseled away and offered for sale on the international art market. In 2003, the Xiangtangshan research team of the Center for the Art of East Asia at the University of Chicago began an intensive documentation project on the caves and their removed sculptures. Like the exhibition Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan, on view at the Sackler Gallery from February 26–July 31, 2011, and a publication with the same title, this feature shares the results of that research. Using 3-D imaging, the team was able to digitally match fragments to their original locations, making it possible to envision some of the caves as they appeared before their tragic despoliation.

View an interactive plan of the site’s seven caves »

Southern Xiangtangshan

A few miles from northern Xiangtangshan, the seven caves of southern Xiangtangshan are arranged in two levels and cut into a stone cliff more than thirty feet high. Although their floor plans resemble those at the northern site, these caves are smaller because they were not sponsored by imperial patrons. Cave 2, on the lower level, housed the most important and largest figures at the site.

The southern caves show a pervasive use of freestanding sculpture created from quarried stone. On many altars, the central Buddha and the innermost flanking figures were carved from the rock of the cave itself. The other sculptures were made separately and set into sockets hollowed in the floor—making them relatively easy to remove from the site undamaged.

Southern Xiangtangshan: Cave 2

Freestanding Sculptures

Two tall, bejeweled bodhisattvas displayed in Echoes of the Past represent deities that accompany the Buddha Amitabha, who presides over the Western Paradise, also known as his Sukhavati. In their original setting—the main altar of the central pillar in Cave 2—these images and pairs of less finely attired bodhisattvas and Pratyekabuddhas together illustrated the divinities residing in Amitabha’s heavenly realm.

Devotional worship of the Buddha Amitabha grew quickly during the sixth century, coinciding with the construction of the Xiangtangshan caves. According to scriptures, believers devoted to this Buddha need only call upon his aid to be reborn in his paradise.

Relief Sculptures

The beauty of Amitabha’s Pure Land is depicted in a massive relief that was carved above Cave 2’s entrance. The relief was purchased by the Freer Gallery in 1921; it is now built into the wall of the museum. Visit Gallery 17 in the Freer to see this and the companion relief that once occupied the cave’s central pillar.

Gallery: Cave 2 at Southern Xiangtangshan

-

Standing Pratyekabuddha

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Purchased from C. T. Loo, 1916, C151

-

Standing Bodhisattva

Freer Gallery of Art, Gift of Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer, F1968.45

-

Standing Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin)

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Purchased from C. T. Loo, 1916, C113

-

Standing Bodhisattva, probably Mahasthamaprapta (Dashizhi)

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Purchased from C. T. Loo, 1916, C150

Northern Xiangtangshan

Northern Xiangtangshan, located near the village of Hecun in the Fengfeng Mining District, is of monumental scale and consists of three main cave temples halfway up Drum Mountain (Gushan). This online feature explores two of the three. The North Cave is the oldest and largest cave. The South Cave is the basis of the Digital Cave—a virtual reconstruction of this damaged Buddhist temple—displayed in Echoes of the Past.

North Cave at Northern Xiangtangshan

The North Cave at northern Xiangtangshan is the earliest and most impressive construction of the entire complex. Although it lacks a dedication inscription, it was probably sponsored by the emperor Wenxuan (reigned 550–59), the first ruler of the Northern Qi dynasty.

Completed during the 550s and popularly known as the Great Buddha Cave, the North Cave is a forty-foot cube. The massive central square pillar is surrounded by four perimeter walls with relief decoration framing deep niches, which contain freestanding sculptures carved from quarried stone.

The cave’s design was meant to convey the eternal nature of the Buddha. It was inspired in part by a holy text called the Lotus Sutra, which became extremely influential during the fifth and sixth centuries. The seventh chapter of the sutra tells of a king who gave up his empire to seek enlightenment and become a Buddha; this pious act moved his sixteen sons to follow the Buddhist path. The patriarch of the Northern Qi dynasty had fifteen recorded sons and likely another, so this theme would have been especially fitting as a statement of the enlightened rule and authority of the royal family.

Gallery: North Cave at Northern Xiangtangshan

-

Seated Bodhisattva

Freer Gallery of Art

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1913.5 -

Kneeling winged monster Buddhist sculpture

Freer Gallery of Art

Transfer from the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution

F1977.9 -

Left Hand of Maitreya

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Transfer from the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

B69 S37A 1922 photograph of the seated Buddha of the Future shows that this hand, which holds the looped end of his robe, was still in place. At that time, the tips of the two raised fingers were broken off, but these fragments appear to have been recovered and reattached.

South Cave at Northern Xiangtangshan

Like the North Cave, the South Cave was commissioned by the Northern Qi court, but it presents a different plan. Lacking a central pillar, it is an open cubical chamber with three altars on the back and side walls. Each altar originally included seven figures arranged symmetrically: a seated Buddha in the center, flanked by three pairs of standing deities. Images of incense burners, lions, and deities appear on the altar bases. Rows of small seated Buddhas occupy the upper niches and cave walls. The ceiling features a large carved lotus.

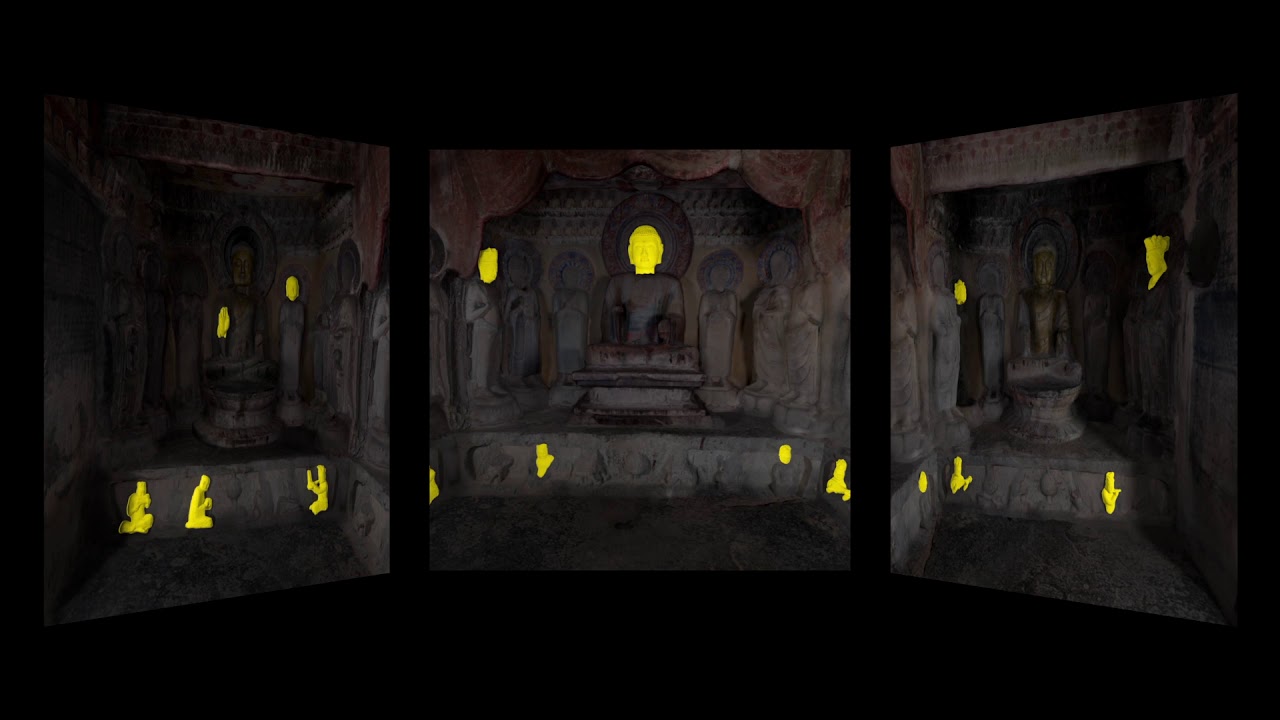

The Digital Cave displayed in Echoes of the Past virtually reconstructs the damaged South Cave.

View the Digital Cave »

Gallery: South Cave at Northern Xiangtangshan

-

Head of a Buddha

Freer Gallery of Art

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1913.67Charles Lang Freer, founder of the Freer Gallery of Art, purchased this and the limestone head below from a New York City gallery in 1913. Their origins remained a mystery for decades.

-

Head of the Disciple Ananda

Freer Gallery of Art

Gift of Charles Lang Freer

F1913.134From 2005–2008, the Xiangtangshan research team of the University of Chicago photographed and scanned scores of sculptures removed from the caves. In 2009, the team collaborated with colleagues at Peking University to scan the South Cave at northern Xiangtangshan. Based on the resulting data, missing elements—including this head and the one above it, which were matched to one of the South Cave's altars—could be digitally restored to their original settings. The application of this 3-D imaging technique could be invaluable in future attempts to restore damaged sites worldwide.

-

Plastic Replicas

These bright yellow heads are three-dimensional printouts derived from digital models of original, sixth-century limestone fragments removed from the South Cave and now held in a private collection. Made of DuraForm plastic, these facsimiles can be accurate down to the finest details, such as surface texture. They make it possible to digitally restore missing fragments to their true locations in the caves.

The facsimiles were produced by the Armour College of Engineering, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, with the sponsorship of Mr. Ralph Wanger, and lent by the Center for the Art of East Asia, Department of Art History, University of Chicago.

-

Portion of the Sutra of Immeasurable Meaning (Wuliangyi jing)

Two modern rubbings of a sixth-century engraved stone original,

ink on paper

Freer Gallery of Art Study CollectionThe caves at Xiangtangshan were the first in China to include engraved sutras, or Buddhist scriptures, in their overall design. These rubbings are of a passage from the Sutra of Immeasurable Meaning that is cut into the interior walls flanking the entrance to the South Cave at northern Xiangtangshan. Such beautifully carved texts not only enhanced the aesthetics of the space, but also contributed to worship; the words may have been chanted during religious practice. This passage describes in detail the appearance of the "radiant Buddha" as being at the center of a great heavenly assembly. It also declares that the Buddha’s ultimate state is formless, a concept that would have encouraged advanced believers to see a metaphysical world beyond the sculptures in the cave.

-

Photograph of inscribed sutra, South Cave, northern Xiangtangshan

Two modern rubbings of a sixth-century engraved stone original,

ink on paper

Freer Gallery of Art Study CollectionThe carver of the inscription worked on a smoothed stone wall, transferring the sutra from paper or brushing the text onto the cave’s surface before engraving. This painstaking process was considered a devotional act. As shown in the rubbings above—produced by pounding an inkpad on damp paper placed over the text—the skilled carver managed to capture the flowing quality of strokes originally rendered with a supple brush. One rubbing has a blank circular space where the inscription has been damaged, as seen in this photograph.

Digital Cave

Weaving together archival photographs and current imaging technology, the Digital Cave displayed in Echoes of the Past virtually reconstructs the damaged South Cave. This immersive experience allows viewers to visit the site and see removed sculptures restored within the cave’s original setting.

The configuration and scale of the three screens of this installation piece, created by contemporary artist Jason Salavon, were inspired by the South Cave’s cubical space framed by three altars. Black-and-white photographs show its damaged state in the 1920s. These are complemented by highly accurate 3-D models, created by the Xiangtangshan research team of the University of Chicago as part of its multiyear effort to photograph and scan removed sculptures and the cave’s interior. The results made it possible to match missing pieces to their original locations.

The Digital Cave was produced and directed by Jason Salavon, with assistance from Travis Saul, 3-D graphics and animation; Michelle Graves, editing; Larry Smallwood, ESAM, LLC, installation production; and Alexander Dunn and Mark Beasley, technical assistance. Video by Hutomo Wicaksono.

Credits

Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan is organized by the Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Major funding is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Leon Levy Foundation, the Smart Family Foundation, and the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation. The catalogue was made possible by Fred Eychaner and Tommy Yang Guo, with additional support from Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund.

Additional support for the Smart Museum of Art’s presentation was generously provided by the National Endowment for the Arts, the University of Chicago Women’s Board, and Helen Zell. Additional support for the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery presentation was provided by the Cotsen Foundation for Academic Research.

The exhibition is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Collections: Chinese Art

Learn More: Xiangtangshan Caves Project at the University of Chicago

Video: Echoes of the Past: The Digital Cave

Detail image, 3-D digital reconstruction with missing fragment in yellow, image by Jason Salavon and Travis Saul.

- Jump To...