Unseen Art History: Wine cup From the Hoi An Hoard shipwreck

December 10, 2021 | Joanna Gohmann

Read on to learn about the journey of this ceramic wine cup from the Red River Delta in Northeast Vietnam to Washington, DC, in this month’s feature of our Unseen Art History blog series, which highlights provenance stories about how objects came to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art.

During the fifteenth century, when Ming dynasty China closed its ports and introduced export bans on ceramics, the Vietnamese ceramic industry flourished. Potters, especially those located near the small village of Chu Dau in the Red River Delta, produced thousands of wares for export to regions as far west as Egypt and as far east as Japan. Potters from Chu Dau likely sculpted this stoneware cup, ornamented with an incised crosshatched pattern and painted with a translucent brown glaze. From Chu Dau, local merchants regularly sent similar cups and other ceramics on flat-bottom riverboats to the port at Van Don, where international merchants then loaded them onto boats destined for overseas locations.

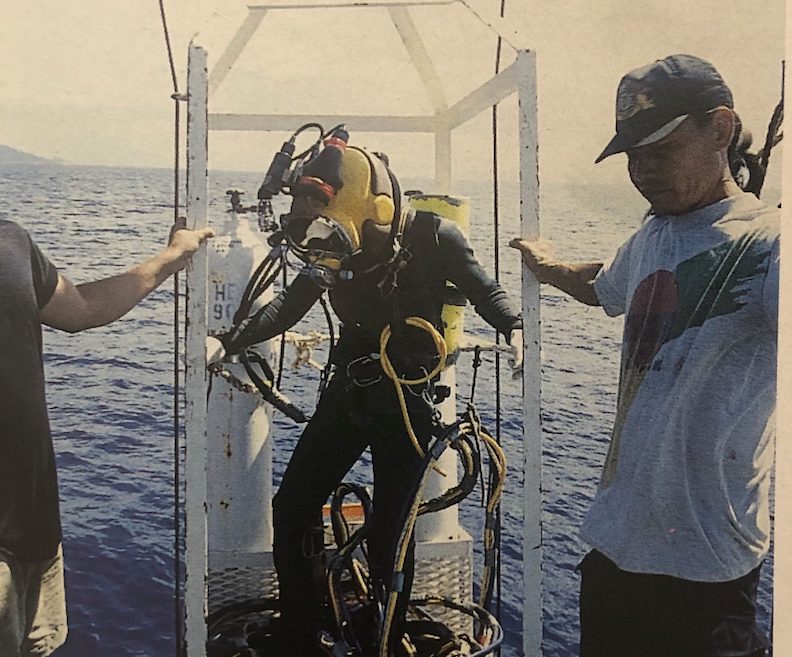

This wine cup was cargo on a teakwood junk—a type of boat with Chinese origins, defined by a high stern and projecting bow—that sank during the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century near the Cham Islands in the South China Sea. The boat, which likely originated in Thailand, was heading toward the Philippines and was heavily laden with ceramic cargo. It likely fell victim to the sea’s treacherous currents or to a typhoon. Seventy meters (nearly 230 feet) below the surface, the boat lay underwater, undisturbed until 1993, when Vietnamese fishermen from Hoi An accidently recovered ceramics with their nets. The fishermen attempted to keep the shipwreck a secret. However, after they strategically dragged metal rakes across the wreckage, hundreds of ceramics were broken and dislodged, thereby floating into other fishermen’s nets, and ultimately flooding the art market. It was not until 1997, when two Japanese dealers were detained in the Da Nang airport with baggage filled with fifteenth-century pottery that the Vietnamese government obtained knowledge of the wreck’s exact location and enlisted the expertise of both archaeologists and the Ministry of Culture.

Once retrieved from the floor of the South China Sea, all artifacts were inventoried, tagged with an excavation sticker that noted the excavation partners and the unique object number, and stored in three huge warehouses. Vietnam’s National History Museum retained all “one-of-a-kind” objects, and the Ministry of Culture distributed hundreds of ceramics to regional museums. The remaining inventory of artifacts, of which the stoneware wine cup was a part, was sent to Butterfields, an American auction house based in San Francisco and owned by eBay. The three-part auction of the “Hoi An Hoard” took place from October 11 to October 13, 2000, both live and online, using eBay’s innovative live auction technology. Indeed, this was a groundbreaking event, as it was one of the first auctions to happen both digitally and in person. Collectors, however, were simply not ready to buy works of art online, as nearly sixty percent of the lots did not sell.

On December 3, 2000, Butterfields hosted another sale that featured pieces from the Hoi An Hoard, including the stoneware wine cup. This sale provided a rare opportunity for avid ceramic collectors to purchase important pieces of Vietnamese material culture at reasonable prices, as museums had already purchased major pieces in the October sale. David P. Rehfuss, a retired officer in the American Foreign Service and one of the founders of the Washington Oriental Ceramic Group in Washington, DC, purchased the wine cup. In 2005, Rehfuss, who also volunteers at the National Museum of Asian Art, presented it as a gift to the museum.

Once accepted into the museum’s Freer Gallery of Art collection, the wine cup featured prominently in the exhibition Vietnamese Ceramics from the Red River Delta, which celebrated the history and impact of such works. This stoneware vessel accentuates the Freer’s collection of Vietnamese ceramics for several reasons. It originates from a major site of ceramic innovation, it has connections to an advanced marine archeological site, it evokes the history of the international ceramic trade, and it has a glaze that is unique among those in the collection. Today, this small but significant cup helps the museum share the expansive history of Asian ceramics.

Further Exploration:

- Louise Allison Court with George Ashley Williams IV and David P. Rehfuss, Ceramics in Mainland Southeast Asia: Collections in the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Washington, DC: Freer Gallery of Art & Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

- Butterfields, Treasures from the Hoi An Hoard: Important Vietnamese Ceramics from a Late 15th/Early 16th Century Cargo [auction catalogue] (Los Angeles and San Francisco, October 11–13, 2000).

- Frank Pope, Dragon Sea: A True Tale of Treasure, Archeology and Greed off the Coast of Vietnam. New York: Harcourt, INC., 2007.