Unseen Art History: Ancestor Portraits—Prince Hongming and Lady Wanyan

August 06, 2021 | Joanna Gohmann

Seventy-three years ago today, these paintings arrived in the United States! Learn about their journey from Beijing, China to Washington, DC, as part of our Unseen Art History series, which highlights provenance stories about how objects came to the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art.

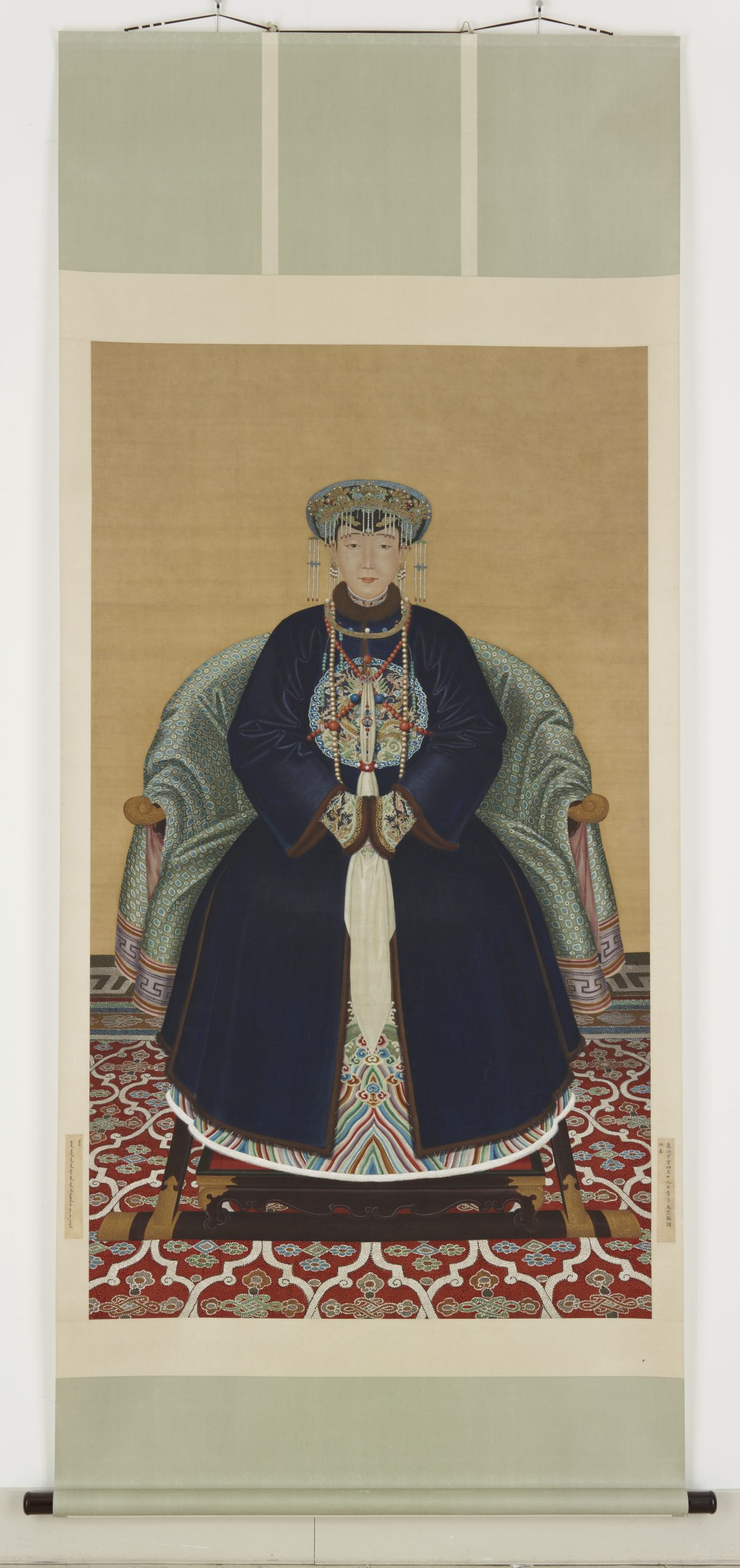

These portraits of Prince Hongming (1705–1767) and his wife, Lady Wanyan (1705–1767), are ancestor portraits that originally served as a focal point of annual family rituals, during which living family members came together to venerate their ancestors. Portraits of ancestors hung above altars at funerary parades, where the living left offerings that included food and incense.

Inscriptions on these paintings indicate that a son of Prince Hongming and Lady Wanyan named Yongzhong (1735–1793) commissioned the portraits sometime after 1767. It is unclear if these are the original paintings that Yongzhong commissioned or if they are copies that were made later. If portraits were damaged, families would commission new versions. As was customary, these portraits were probably inherited by Hongming and Lady Wanyan’s descendants, who parted with the portraits sometime during the early twentieth century, likely consigning them to the antique trade.

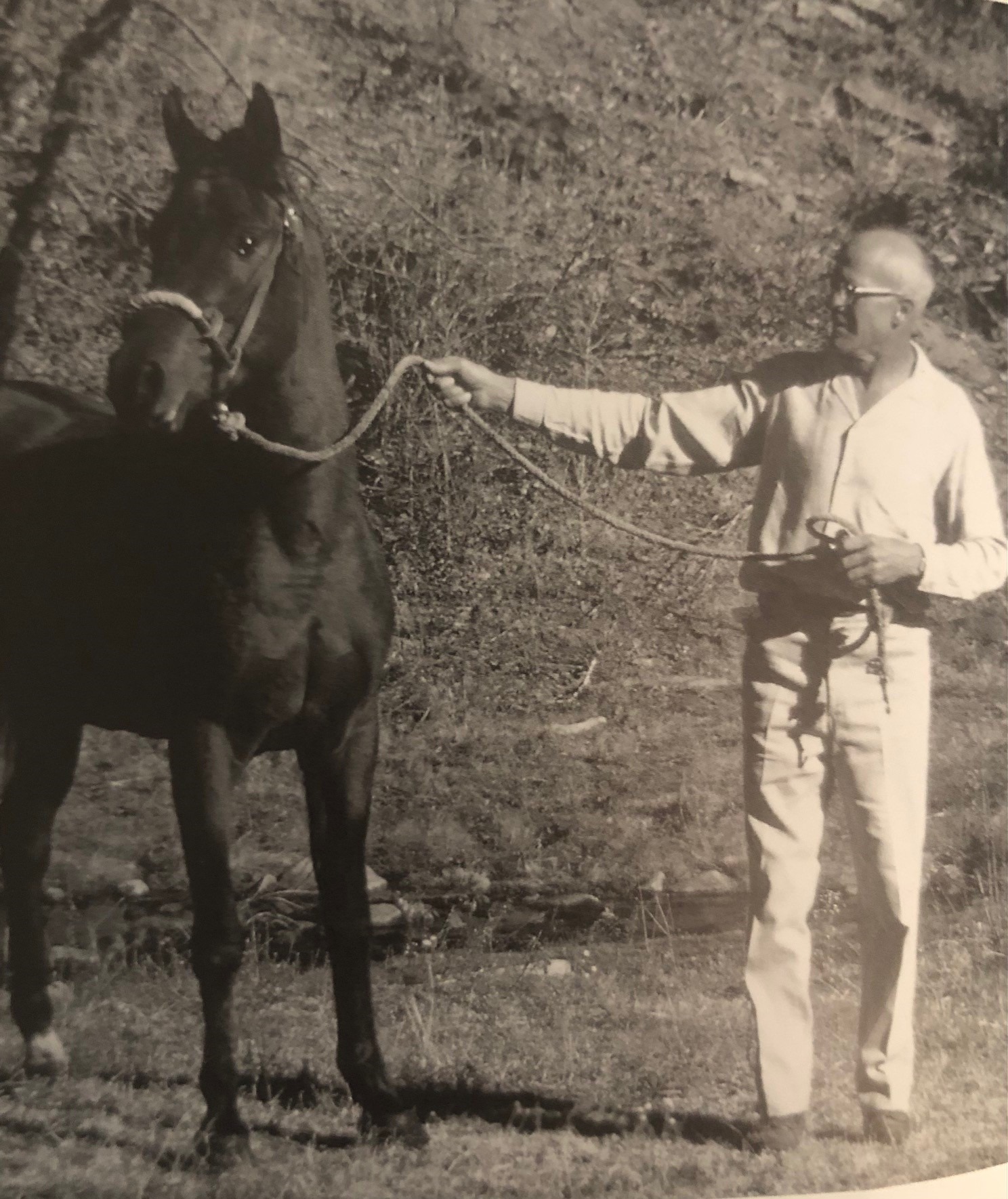

Wu Laixi 吳賴熙 (d. ca. 1949) was a collector and antiquities dealer in Beijing who labeled himself the country’s first serious collector. He purchased these paintings for his personal collection of Chinese ancestor portraits. In the 1940s, when war with Japan and domestic turmoil threatened the security of private art collections, Wu worried about his financial security and the fate of his collection in China. He therefore wrote to Richard Pritzlaff (1902–1997), a fellow collector and rancher in New Mexico whom he had met years before when Pritzlaff visited China. Between 1940 and 1948, Wu sent three shipments of portraits and other art objects to Pritzlaff’s ranch in exchange for the American collector’s promise to protect the portraits.

Seventy-three years ago today, Pritzlaff received the final shipment of portraits. Wu Laixi died in 1949 before he could retrieve the works, so his son vested ownership of his father’s collection with Pritzlaff.

For years, Pritzlaff proudly displayed these paintings in his home. In the early 1980s, the former presidential candidate Ross Perot (1930–2019) visited Pritzlaff’s ranch to inspect his Arabian horses. While there, Perot fell in love with the collection. After his visit to the Pritzlaff ranch, Perot purchased the ancestor portraits and pledged to construct a museum in Texas to display and preserve them. By 1986, Perot still had not fulfilled his promise, and a year later, Pritzlaff bought the collection back from Perot and began searching for an established museum to house and display the works.

In 1989, Pritzlaff reached out to the Freer Gallery of Art & Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and by October 1990, the museum agreed to acquire eighty-five ancestor portraits from Pritzlaff’s collection, including both portraits shown here. These portraits are among the highlights in the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery’s collection and attract international scholarly study.

From personal objects at the center of family rituals to prized art objects displayed in a private home, and finally to objects preserved for public appreciation and study, these portraits have been enjoyed by a variety of audiences and have held a variety of meanings.

To learn more about their original context, and see other ancestor portraits in our collection, visit our resource Teaching China with the Smithsonian.

Dive even deeper with the online catalog from our 2001 exhibition Worshiping the Ancestors: Chinese Commemorative Portraits by Jan Stuart and Evelyn Sakakida Rawski.

Portrait of Lady Wanyan, primary wife of Prince Hongming (1705–1767), Qing dynasty, 1767 or later, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, Purchase—Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program and partial gift of Richard G. Pritzlaff, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, S1991.53

Image 1 of 2

Portrait of Prince Hongming (1705–1767), Qing dynasty, 1767 or later, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, Purchase—Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program and partial gift of Richard G. Pritzlaff, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, S1991.61

Image 2 of 2