Mountains, Museums, and the Mekong Delta: Travels in Vietnam

September 11, 2019 | Emma Stein

Emma Natalya Stein, National Museum of Asian Art assistant curator of South and Southeast Asian Art, shares scenes from her recent journey to Vietnam

Throughout premodern Southeast Asia, mountaintop areas were selected for development of spacious temple complexes that attracted religious practitioners. Called rishis, meaning ascetics or sages, these practitioners sought to temporarily escape the trappings of daily life and concentrate on spirituality. The sites of the complexes were conducive to such focused efforts. They were positioned in relation to natural wonders—mountains, volcanos, waterfalls—that captured the senses and immersed the inhabitants into their surroundings.

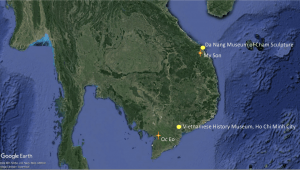

Sites visited, Vietnam, July 2019

My Son, Vietnam

Poised on the hills of central Vietnam, My Son Sanctuary is one such site. Its nine surviving temple compounds within a two-kilometer circuit are a vestige of what once was dozens of sacred structures covering a vast expanse. Within each compound, myriad buildings provided discrete spaces for various ritual practices. Still, the remaining temples and the sculptures that they housed provide an unparalleled archive of Cham culture and history. They also reveal the impressive development of Champa architecture over more than half a millennium of construction.

Royal court dance lintel, eleventh century, My Son, Vietnam (Da Nang Museum of Cham Sculpture)

Who were the Chams? As far as their early history is known, the Chams were originally an ethnically Austronesian group of seafaring peoples who settled along the coast of what is now central Vietnam in the early centuries of the common era. Keeping their focus on the rivers and the seas, they developed a loose network of trading polities that operated more or less independently and played important roles in long-distance connections. The Chams were among the earliest cultures to adapt, incorporate, and transform the Buddhist and early Hindu traditions of art and ritual that flowed into Southeast Asia from abroad.

Dancers and Musicians, Chien Dan Temple, Vietnam

Deeply connected with South Asia and neighboring mainland Southeast Asian traditions of building, the Champa architects infused their temples and representations of deities with a sense of liveliness and grace. Figures of dancers and musicians are a recurrent theme.

Dancing Shiva, eighth century, My Son, Vietnam

Although the temples have deteriorated and are no longer in use today, the natural beauty of the surrounding landscape, its rolling hills, its luscious fragrances, and its shifting soundscapes of wind, water, and insects has remained largely untouched. Walking uphill to the temples, I passed a roiling stream and looked out into a lush, thick ocean of green jungle, denser than I’ve seen elsewhere in Southeast Asia. The undeveloped nature of the mountain shows that this was not an urban center but a place of retreat.

Farther up the slopes, the hook-shaped contour of a higher, even more imposing mountain becomes visible. Locally known as Garuda Peak, it serves as an orientation point from anywhere within the My Son area.

My Son, Vietnam

“Sanctuary,” as it is commonly known, is indeed a fitting term for My Son. It was a place where Shaiva ascetics (religious practitioners devoted to the Hindu god Shiva) removed themselves from the Cham’s royal capital of Tra Kieu. The temples are organized on opposite sides of a narrow river that runs north-south. The sanctums open either east or west to face the river depending on which bank they are situated. The orientation toward a body of water is similar to the Cambodian temple-complex of Koh Ker, where the shrines are arranged around a central reservoir. At the My Son Sanctuary, however, it is done with even greater consistency. Directly facing each other, the temples’ positions give the site an integrated feeling.

Even within this tightly woven complex, the variety in shape and size of the buildings indicates diverse functions. Centrally located and expansive, temple group B is thought to be the primary royal monument. Set apart from the others in the northeastern corner, group E seems to have been a place for more austere forms of practice that involved a level of retreat even from the seclusion of the jungle hermitage.

Pedestal from My Son E-1, eighth century (Da Nang Museum of Cham Sculpture)

The great pedestal from temple E-1 shows Shaiva ascetics engaged in the rituals they presumably would have practiced here. In vignettes carved on the pedestal, hermits read manuscripts, play stringed instruments, or converse within caves. Their hand gestures (mudras) suggest they are engaged in meaningful discourse.

Tympanum of Vishnu on the serpent Ananta, eighth century, My Son, Vietnam (Da Nang Museum of Cham Sculpture)

Most of the sculptures and decorative stonework has been removed and is preserved in Vietnamese museums, leaving only the brick core of the temples in situ. A visit to the Cham sites, therefore, requires some imagination. Temple group E still retains several statues dispersed throughout the site. Together with the temple’s most important sculpture—the great pedestal—these images would have inspired and instructed the people who saw them, serving as a mirror for these spiritual aspirants.

Royal court dance, eighth century, My Son, Vietnam (Da Nang Museum of Cham Sculpture)

Scholars have pointed out the importance of music and dance both in the royal court and, notably, among a particular sect of Shaiva practitioners. Called Pashupatas, these ascetics traveled widely and served as teachers and ritual specialists throughout South and Southeast Asia. Looking at their images now, we can almost hear their music and the beat of their drums at the time of the temple’s greatest activity.

It is tempting to imagine these jungle hermitages as places that operated “outside the system,” so to speak. However, it is important to acknowledge how utterly dependent they were on the courtly world down below. Architecture at such a large scale and built of costly materials required elite patronage. The Pashupatas were often royally sponsored, and every Champa king built, renovated, or made pious offerings to a temple at My Son. When the court temporarily shifted its preference to Buddhism in the tenth century and built the massive Buddhist temple Dong Duong, this Shaiva epicenter reduced in activity. When court preference returned to Hinduism, activity resumed accordingly at My Son.

In addition to its secluded beauty and strategic position close to the Champa capital city, proximity to natural resources helped determine My Son’s location. At the bottom of the hill is a river with a rich bed of sandstone, which served as the main quarry for the temple construction. It doesn’t take long to notice the right angles that indicate cut marks in the rocks. It is possible the choice of the temple location was due to the proximity of the sandstone.

Over the centuries, the architecture and surrounding landscape have been severely damaged by jungle. However, a visit to My Son also requires an encounter with destruction from recent history. In 1969, US military forces bombed a Viet Cong area that included the temples of My Son. Signs perched above deep round troughs in the earth inform the visitor these are the resultant bomb craters. Other signs warn not to venture from established pathways, as land mines linger undetonated in the jungle.

A shift in light in the late afternoon signals the approaching rain. Soon I hear claps of thunder begin to ricochet around the valley. As I head down the hill in early droplets, the jungle grows loud around me.

My Son may be the most dramatically situated complex of Cham temples, but it is not the only one in the area. At daybreak the next morning, I set out for three other temple complexes, situated close to the coastline in the alluvial flatlands to the south of Da Nang.

The alluringly octagonal shaped tower is all that remains of the Bang An temple complex. It is located upstream from Hoi An, now in a relatively abandoned condition, though it is an archaeologically protected monument.

The soaring, tapered tower resembles a jyotirlinga, the sign of Shiva in light form. Although less frequently found in art from elsewhere in South or Southeast Asia, the linga with a flame motif is an important emblem in Cham art. To make the connection with light explicit at Bang An, the tower once contained sandstone ornamentation in the shape of flames.

Further south are the brick triple-shrines of Chien Dan and Khuong My, the remains of two massive complexes once replete with sculptures.

Khuong My temple, tenth century, Vietnam

Many of Khoung My’s tenth-century artistic marvels can be seen at the Da Nang museum. However, in addition to their proficiency in stone, Cham sculptors were masters of carving in brick. The walls of both temples are elaborately carved in vegetal scrollwork and intricate geometric patterns that, along with the constant buzz of the tropical landscape, enliven the spaces and give the temples a vibrant sense of movement.

The temples of Champa were a long-awaited destination for me, and I find that fieldwork to new sites is always best done alone. Encountering a temple on my own gives me time to observe and to notice, to let my eyes adjust to unfamiliar forms, and to allow my mind to call up comparisons with images I’ve seen in other contexts. I move slowly through the space and alternate between periods of observation and photography.

Magnificent as they are, however, the Cham temples were not what brought me to Vietnam on this trip. I was there to lead a workshop on the history and cultures of the Mekong Delta region, which is situated at the southern tip of present-day Vietnam. Organized by SOAS London in collaboration with the Museum of Vietnamese History in Ho Chi Minh City and the National Museum of Asian Art, our workshop brought international experts in art history, archaeology, and related disciplines together to reassess Mekong Delta cultures, particularly in relation to the Vietnamese history museum’s collection.

At the workshop’s culmination, we made a field trip six hours south by bus from Ho Chi Minh City to visit regional archaeological museums and active excavation sites in the Delta. Research continues and the results are currently confidential, but documented findings have already revealed that the Delta was well connected with extensive, long-distance networks that spanned the known world. Stay tuned for forthcoming publications on this topic!

Learn more about Vietnamese history and culture through related bibliography