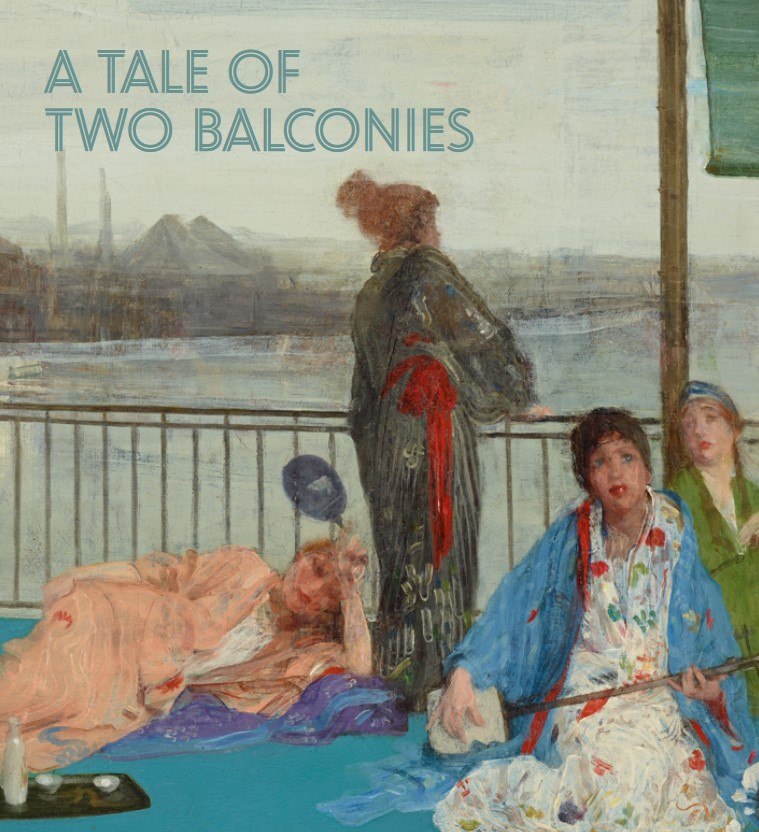

Just Published: A Tale of Two Balconies

December 20, 2024 | National Museum of Asian Art

What’s different about the view from a balcony? The geometry of a balcony creates a picture within a picture. It constructs a view, at once private and public, defined by a building and location, to visualize and juxtapose different worlds.

What’s different about the view from a balcony? The geometry of a balcony creates a picture within a picture. It constructs a view, at once private and public, defined by a building and location, to visualize and juxtapose different worlds.

Our latest publication, A Tale of Two Balconies, examines two balcony views: Katsushika Hokusai’s The Sazaidō of Gohyakurakanji (F1974.63) and James McNeill Whistler’s Variations in Flesh Colour and Green—The Balcony (F1892.23a-b). A double-sided format divides the book into two equal parts, each by a different author, that meet in the middle. The center section includes hands-on activities that bring the balcony to life.

This book proposes a new model for comparative art history. Whistler’s work is often understood as an instance of Japonisme, a late nineteenth–century Western art trend of incorporating and appropriating aspects of Japanese art. But this book is not about Whistler, Hokusai, or Japonisme. Instead, A Tale of Two Balconies attempts to move beyond reductive narratives of influence. Each artist made careful choices about what to include, discard, or adapt based on a variety of possibilities, their artistic practices, and contemporary currents. As much as a balcony is a physical structure, it is also a compositional and intellectual framework that can be applied to many artworks and contexts.

The pop-out page for the toy theatre diorama lies flat on table. Text on the back indicates how to fold each part. The front reappears with the center cut out. The center piece is divided into two pieces that make an arch for the top of the stage. Turned over to the back again, the edges of the stage are folded backward. On the front, the parts with the balcony seats are folded forward. A close-up view of the back shows that a bar across the top is folded forward as well. A hand shows tape applied to each of the top arch pieces and then attached to the stage. The pop-out theatre stands up on its own on the table.

The two halves of this book share a parallel organizational structure. Mirrored sections examine the details of each work: the geographical location; the pictorial devices, innovations, and pigments; the visual strategies; and how the balcony serves as a framing device for landscapes that combine the real and the imagined. Other sections address broader contexts, such as race and gender dynamics, tourism and urbanization, globalization, and the circulation of ideas and materials.

The pop-out page for the toy gate diorama lies flat on table. A long blue rectangle is removed from the top. Scissors appear and then cut across the dotted cut line on the top of the page. The roof of the gate is shown detached from the main structure. Then the figures of men fighting, two women, and two dogs are shown detached as well. Turned over, the back of the gate shows the sides folded backward and the square on the right edge folded forward. The gate now stands up on its own on the table. The back of the roof is held up by a hand, and the text instructions read “Position this element over the middle of the gate, with this edge as the top of the roof.” A hand holds up tape. On the back, the roof is positioned against the top of the gate. Back to the front view, the roof now sits atop the gate. The figures fighting are placed in front of the gate. The figures of the women and the dogs are attached to the stand with the figures fighting.

You are invited to remix these works and their themes in the innovative central section of the book. From pop-out dioramas to collage and coloring, the enclosed exercises help you see these balcony views anew. Such close considerations allow us to appreciate each work’s particular features. You may also want to take this toolbox of interpretive approaches with you, whether to interrogate other images or to create new ones.