Dress intersects with everyday life in a way that few areas of art history do. Everyone participates in the fashion economy by purchasing and wearing clothes. Even the most unworldly understand the sharp distinction in impression created by jeans and a T-shirt versus a well-pressed suit. This intersection with the quotidian, and with popular culture throughout history, provides the student of dress with a valuable vantage point from which to address a range of questions.

Exploring these topics, the first open-access edition of Ars Orientalis, themed “New Research on Dress across Asia,” is now live. Edited by Nancy Micklewright, head of public and scholarly engagement at the Freer|Sackler, Ars Orientalis 47 considers key issues in the study of dress in general and, more specifically, dress in Asia. These issues include the divide between the timelessness of “traditional” dress and the fast-paced changes of what we call “fashion.” Also considered are the categories of evidence that come into play, the ways in which “orientalism” has affected the study of dress, and contemporary approaches to the field.

The eleven articles in this volume feature diverse approaches and methods, applied to material that runs the gamut from individual garments or a specific type of fabric to representations of dress. Together they cover a wide swath of time and geography across Asia and the Middle East.

As with previous digital volumes, Ars Orientalis 47 features web-based supplements to the printed edition. These include Digital Initiatives, a column that explores digital tools, resources, publications, and learning opportunities in art history and related fields, with a special focus on topics relevant to each volume.

What is Ars Orientalis?

Ars Orientalis is a peer-reviewed annual volume of scholarly articles on the art of Asia and the ancient Near East. Founded in 1954, the journal is copublished by the University of Michigan’s History of Art Department and the Freer|Sackler.

From its inaugural issue in 1934, Ars Islamica (the Islamic art-focused predecessor of Ars Orientalis) was lauded for its presentation and design quality. The founding editor of the journal sent copies from the University of Michigan to scholars across the globe, and a flurry of responses quickly arrived from New York, Paris, and Istanbul. They congratulated him on the publication’s “extraordinarily beautiful” and “splendid” presentation, which, one letter noted, was “particularly welcome and creditable in these days when the scientific effort has a tendency of being trimmed down to the practical end and utilitarian.”

Practical and utilitarian the journal was certainly not.

The following year, University of Michigan deemed it worthwhile to splurge on even higher-quality paper. It also approved an additional two hundred specially bound volumes for publication during the university’s centennial celebration in 1937. Production decisions like these contributed to the journal’s reputation as, the Freer Gallery’s first director noted, “a most excellent publication in its field, with certain features, such as size, paper, wealth of illustrations, in which, as far as I know, it is unsurpassed by any journal in its class.”

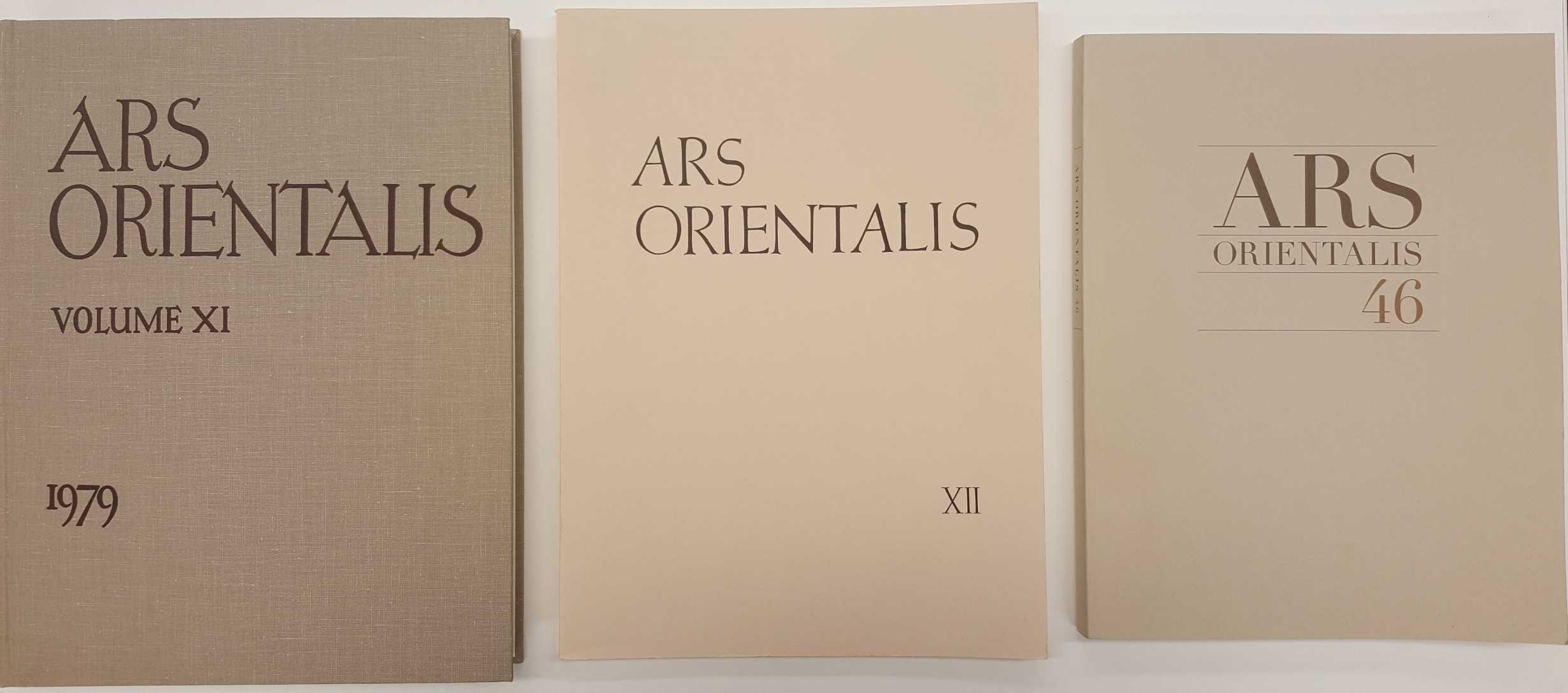

A decade later, the journal had undergone changes in its editorship, breadth of content, and name, but Ars Orientalis maintained the same appearance and design standards set by Ars Islamica.

Publication design moved to the forefront of discussion again in 1956, when the director of the University of Michigan Press baffled the chairman of the university’s fine art department at a business lunch by noting that “the most striking thing about Ars Orientalis is its magnificent and expensive format.” He explained that the journal’s large size (it measured 9” by 12”), hardcover binding, and full-page images were more akin to the coffee table books of art connoisseurs than modest scholarly serials. In short, he suggested, the luxe format and scholarly content of Ars Orientalis were contradictory. It was decided that changing the content to appeal to connoisseurs was out of the question. Designing a more modest and economical version of the journal, however, had potential.

It wasn’t until the late 1970s that this recommendation took effect in the form of a so-called “New Ars Orientalis.” By this time, the journal had a new editor and the Freer Gallery a new director. Together, over the course of nearly three years, the two worked on a cost-reducing redesign. Though they began the project with such radical ideas as including advertisements and a mustard yellow cover, in the end the traditional, elegant typeface and brown-on-tan color scheme endured into the 1980s. The first volume of the “new” series debuted at the end of 1981 with a paperback format, pared-down cover design, and ten-point body text rather than the “luxurious” twelve-point font of the past. Adjustments to the design continued, the director of the Freer at one point taking things into his own hands by “using the Xerox machine and a pair of scissors” to refine the title page’s layout.

A handful of volumes in the late 1990s and early 2000s saw more of a departure from Ars Orientalis tradition in terms of layout and typefaces, even including cover images. But in 2004, a new design closely based on the historical look of the journal was established and would remain for over a decade.

In 2014, Ars Orientalis entered the digital realm with a volume on arts of death in Asia. And in December 2017, the journal launched its newest volume as open access, making its content available to read online.