Hokusai: Making Waves

March 23, 2012 | Howard Kaplan

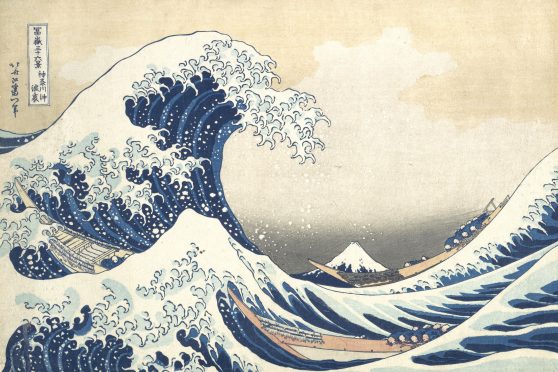

Hokusai: 36 Views of Mount Fuji opens Saturday, March 24, as part of our Japan Spring celebration. In honor of the exhibition, Bento presents a series of posts on the life and times of Hokusai, the famed artist behind the esteemed series that includes the iconic print Under the Wave off Kanagawa, better known as The Great Wave. This article was written by Victoria Dawson and previously appeared in Asiatica magazine.

In the 1850’s—the decade after Hokusai’s death—Japan was opened up to the West and paintings and prints began to flow to Europe and into America. Over the next fifty years, Hokusai gradually emerged in Western eyes and in the Western imagination as the Asian artist par excellence. Much has been written about his influence on designs of European and American artists in the late nineteenth century. Indeed, in Vienna, at the 1873 international exhibition, a major exhibition of Hokusai works underscored the high degree of popularity that he enjoyed in the West. But through most of the last century, beyond a relatively small group of researchers and collectors, the artist was largely identified in the popular imagination as a print designer. His most famous work, The Great Wave from the print series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (circa 1830–33), is virtually synonymous with Japanese art—and so ubiquitous that it can be found almost anywhere that ink can adhere to a surfave—from tote bags to magnets. [The print can be seen at the Sackler Gallery as part of the exhibition on view from March 24 through June 17, 2012.]

Hokusai was someone with a very deep sense that wherever he was, it was not the final place—he was always looking for something beyond. He was an individualist whose art seems infused with a sense of irony, hauntedness, and a search for meaning. His prolific productivity, his cherished independence, and his groundbreaking visual techniques suggest a man who was obsessed with something other than money or social standing.

Then, as now, there were scores and scores of artists who were content with the status quo, satisfying rather than challenging the expectations of their viewers. Not so Hokusai. Consider, for example, the contrast between two prints of waves, created within several years of one another. In The Great Wave, Hokusai presents a rather generous vision of sweeping waves with Mount Fuji in the distance. A print he created only a year or two later offers a claustrophic alternative: In Chosi in Shimosa Province (circa 1833–34, from the series One Thousand Pictures of the Ocean) the waves cleave to a sharp diagonal line, crashing against the jagged rocks and shoals. A second, distant fishing boat offers none of the reassuring stability that Mount Fuji provides in the earlier print.

“There is no escape. Visually, Hokusai doesn’t allow it,” says Jim Ulak, senior curator of Japanese art at the NMAA. “He seems to say, ‘Well, you were comfortable with The Great Wave? Now, I’ll give you something to be afraid of—a darker vision, a sense of being trapped.’ Why would Hokuasi have done that? Not to make the viewer feel comfortable. You can always expect him to pull the rug out from under you.”