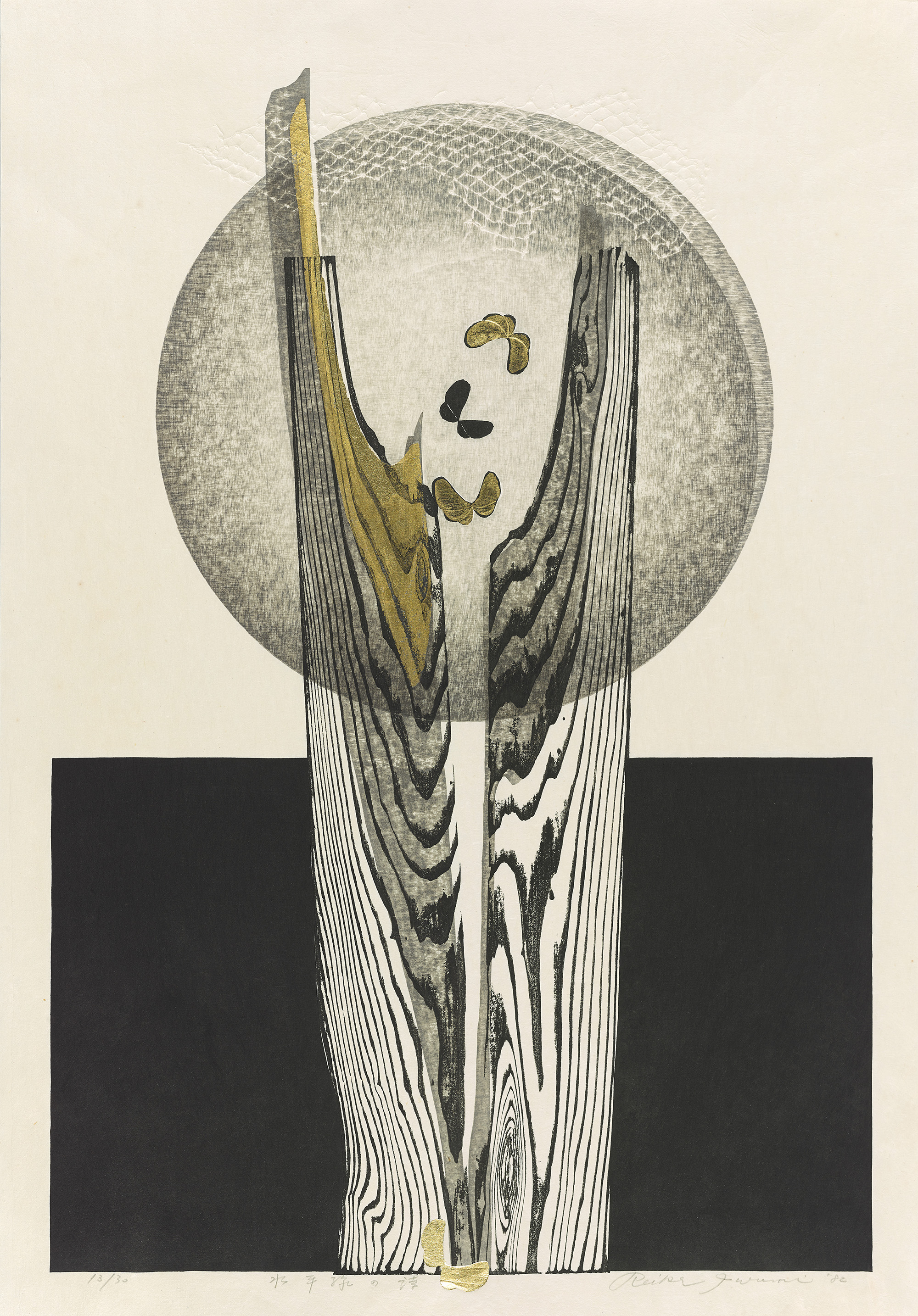

Using a printing process known as collagraph, Iwami likely pasted a fishing net to a block to print this netting form. The netting here is half-embossed: the areas where the netting overlaps with the white paper are three-dimensional, but the net lies flat where it meets other printed areas. Iwami probably embossed the entire net, but the areas that were overprinted with other compositional elements gradually flattened as she applied repeated pressure to the paper. You can still see the effects of the original embossing in the gold leaf.

All Iwami’s prints incorporate pieces of natural driftwood. She printed directly from the driftwood using a technique known as mokume-zuri. To make the print, slightly dampened paper is lightly laid over the prepared driftwood block, and pressure is applied from the back to transfer the woodgrain pattern onto the paper. Many of Iwami’s works deal with themes of wood and water, making driftwood a symbolic and apt material for her oeuvre.

The butterfly shows up in many of Iwami’s prints, including Ocean Ripple (E) (S2019.3.814), Water Flame (S2019.3.817), and Horizon B (Unasaka) (S2021.5.100). Furthering her engagement with natural forms and themes, the motif plays with the boundary between abstraction and representation. In fact, the artist has said that the butterfly is actually a stylized representation of water splashing back on itself. In this print, Iwami has placed one butterfly at the bottom of her composition, imposing on the space typically reserved for the artist’s signature and edition information. Many of Iwami’s works break from the conventional, rectangular picture plane in this fashion.

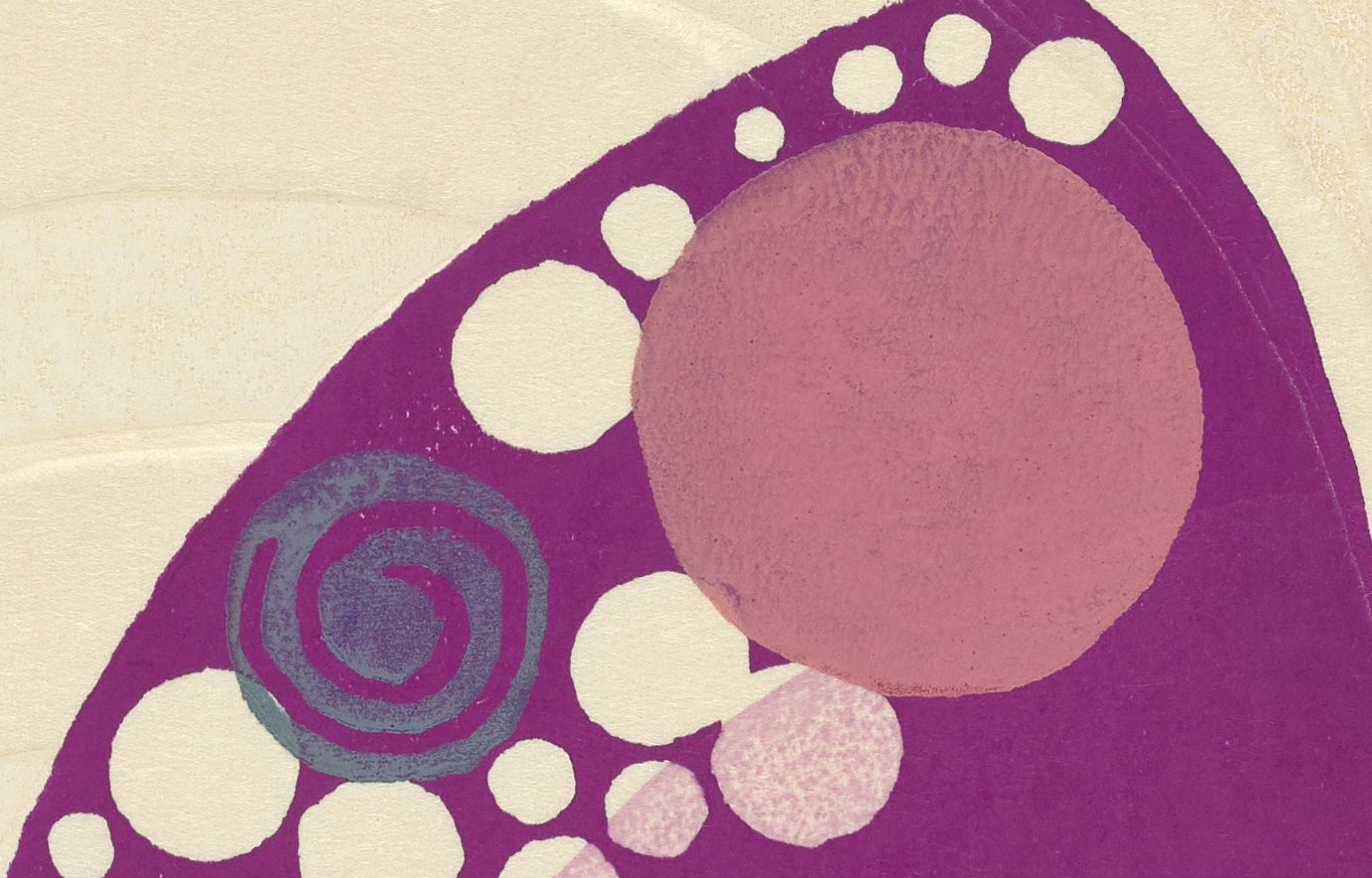

Yoshida was known for her bright color palettes, which she achieved with newly available synthetic pigments made by the NICKER company, founded in 1950. Unlike traditional pigments, the particles in NICKER paints were coarse and remained on the surface of the washi paper instead of penetrating into it, allowing Yoshida to get the strong colors she preferred. According to her daughter, the printmaker Yoshida Ayomi, Chizuko was unique in her use of these pigments and did not worry about the so-called “rules” of traditional printmaking. Instead, she always chose what she liked best.