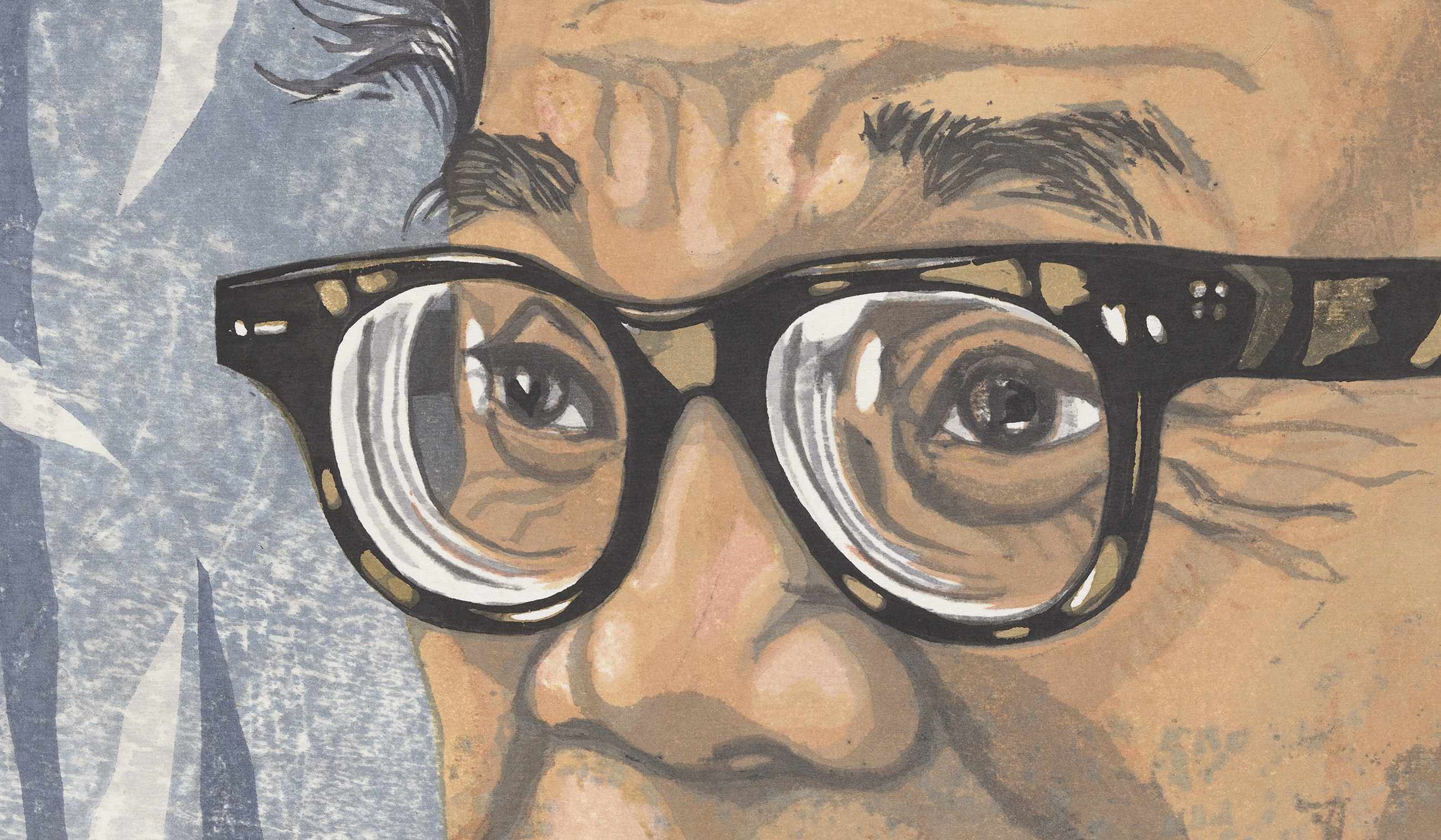

Munakata Shikō was famously nearsighted and wore very thick glasses, putting his face mere inches from his canvas or block as he worked. This detail, carefully observed by Sekino, suggests the two artists’ friendship. Sekino and Munakata both grew up in Aomori city, Aomori prefecture. Eleven years younger than Munakata, Sekino would follow the older artist as he sketched all over their town, sometimes carrying his painting tools for him. Munakata was famously exuberant and unconcerned with decorum, as his wild hair and unshaven face attest. Still, Sekino chose to represent Munakata at a moment of introspection, moving beyond Munakata’s outward appearance to convey an intimate portrait of his friend.

In this portrait, Munakata’s work is just as critical to our understanding of him as his physical appearance. The two towering figures in the background are taken from Munakata’s print series The Ten Great Disciples of Buddha (1939). Munakata used the blocks for those prints to line his underground air raid shelter. Because the blocks were buried, they survived the fire that destroyed his home and several of his early works. He dug them up after the war and made new prints with them, which won major prizes at the São Paulo Art Biennial in 1955 and the Venice Bienniale in 1956. The prints are characteristic examples of Munakata’s powerful, energetic, and purposefully folk carving style, using bold black lines on a white background. Another representative example is Munakata’s self-portrait (S1991.144).

Sekino incorporates Munakata’s unique style while recreating his work. In addition to the figures of the disciples, the forceful use of the baren (a flat, circular printing pad made of coiled bamboo fibers) has left an energetic tangle of lines that evokes Munakata’s personality.

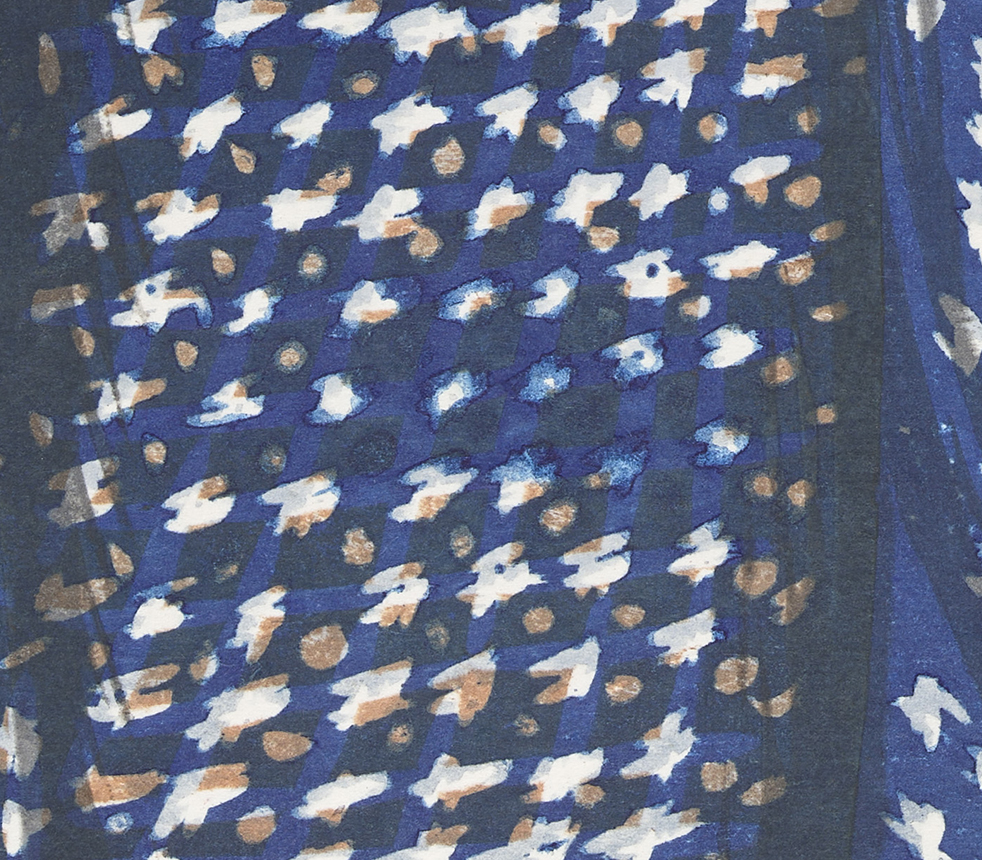

This small portion of Munakata’s indigo kanoko shibori (tie-dyed deer spot) print kimono has bled beyond its intended area, perhaps due to an excess of pigment being applied or a misalignment of the different blocks used. This is one example of how individual print impressions can vary within the same edition.

NMAA has another impression of this work (S2021.5.250). Changes ranging from subtle to significant can occur during the printing process. The artist may make changes to the composition or the printing technique, varying the amount of pigment applied, the pigment colors, or the pressure applied during printing.

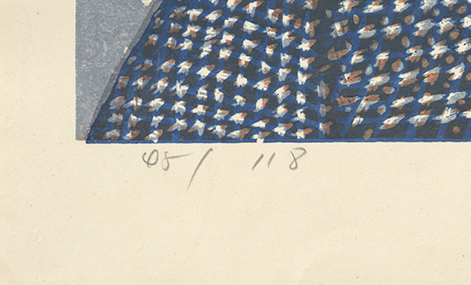

Sekino was part of the sōsaku hanga movement, in which all aspects of a work’s production, including designing, carving, and printing, became the responsibility of the artist alone, a break from the Japanese printmaking tradition. But by the mid- to late 1950s, the demand for Sekino’s work outpaced his ability to print in this way. He created a studio and hired artisan printers to produce his designs. As a result, his printmaking process became less experimental. One distinction between a Sekino work produced by his studio and one produced by the artist is the edition size. Generally, editions higher than thirty were made by his studio.

Whereas Sekino’s self-produced prints were made a few at a time, his studio-produced works were made all at once, creating greater uniformity among the different impressions. The numbering of any print artist’s works may or may not be in the same order as they were printed. It is a common misconception that earlier impressions are always of greater value than later impressions, as the numbers can simply be a way to distinguish between them. Which of these works do you prefer?

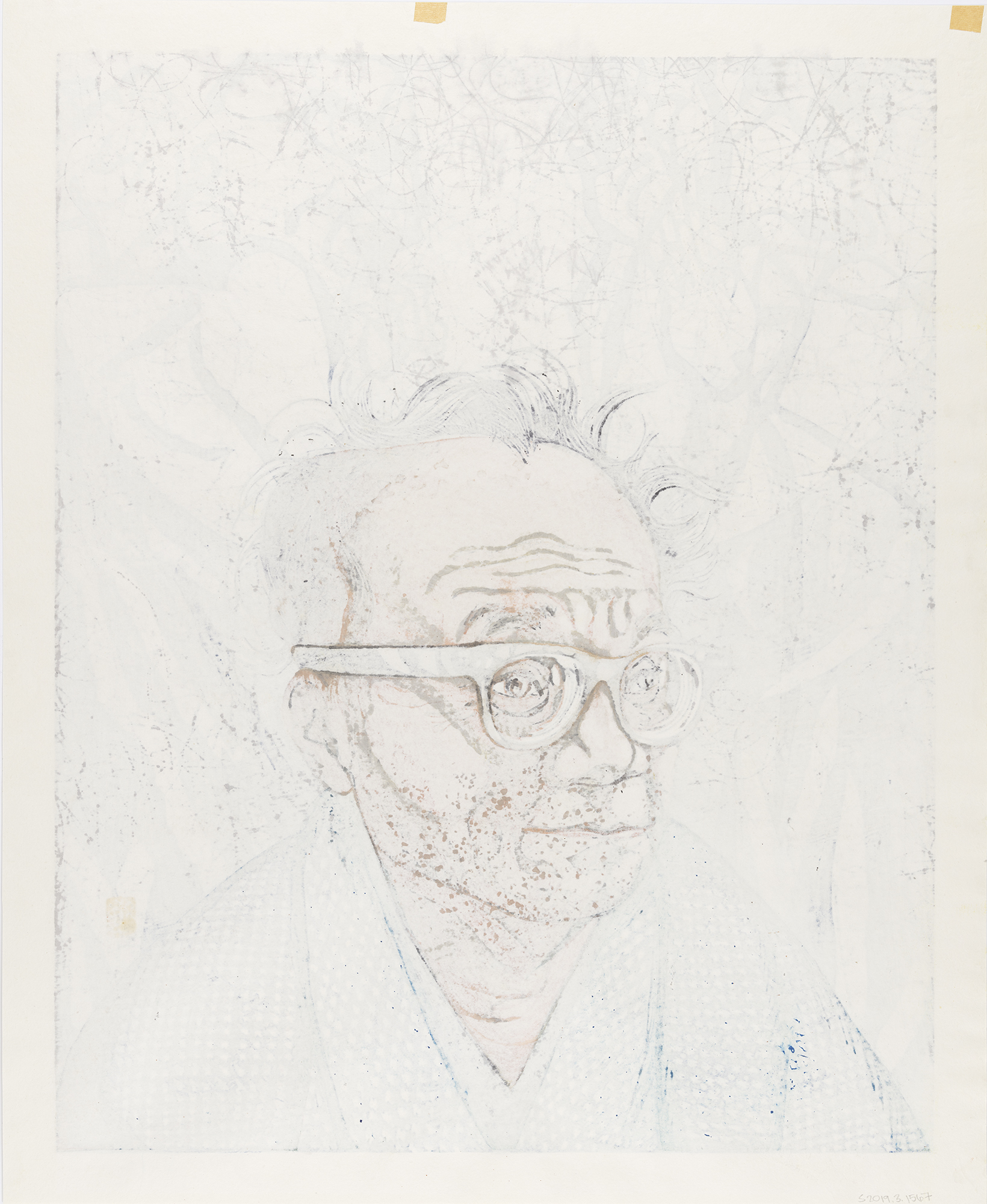

Turning this print over helps us better understand how it was made. Prints are typically made using separate blocks for each color and for specific details. The areas where the pigment has seeped through the paper show where different colors have been layered on top of each other to create the image. As more pigment is added, the pigments soak through to the back. Here, we can see that the details of Munakata’s face—his stubble and wrinkles—were achieved using several blocks.