Haniwa, meaning “circle of clay” in Japanese, are hollow, earthenware funerary objects that were placed on top of and around the colossal mounded tombs (kofun) of the ruling elite during the Kofun period (ca. 250–552). The earliest haniwa were clay cylinders, but over time they developed into hollow sculptural forms that included human figures, houses, animals, and ceremonial objects. The exact purpose of haniwa is unknown, and it is probable that their ritual meaning changed over time as funerary practices evolved.

Saitō’s use of the haniwa motif was part of a larger trend in Japanese art and architecture of the 1950s that looked to Japan’s ancient past to develop a new form of modernist expression. During World War II, certain genres of Japanese art had been used to support nationalist ideology. After the war, some Japanese artists and architects engaged in the “tradition debate” (dentō ronsō), arguing about how to celebrate Japanese culture without furthering the militarism that had come to be associated with nationalistic art. One solution to this debate was to look to Japan’s prehistoric periods, which were seen as the root of Japanese aesthetics but could be freed from wartime associations. Another advantage of prehistoric art was that their simplified forms resonated with the modern trend of abstraction. Other modern printmakers, such as Inagaki Tomo’o and Mabuchi Toru, and modernists, such as Henry Moore and Isamu Noguchi, were also inspired by haniwa.

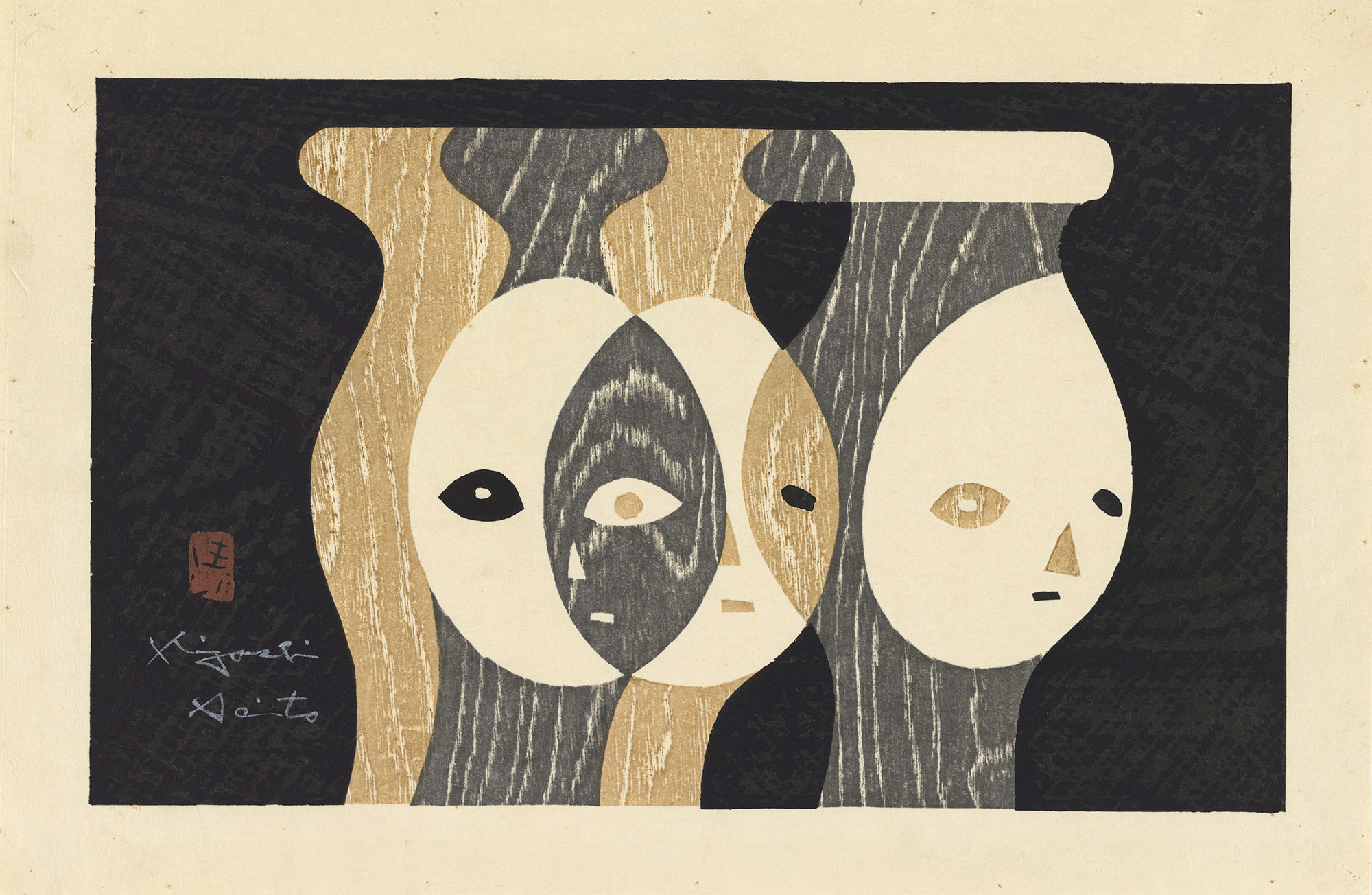

One of the most distinctive features of Saitō’s prints is his use of woodgrain printing (mokume-zuri). In this method, the artist prints directly from a visibly grained piece of wood rather than carving an artificial grain pattern into the block. Sometimes the artist will burn the wood with a blowtorch to weather it, or emphasize the grain by clearing sections with a wire brush or soaking the block in water. In the postwar period, artists used many varieties of wood for this technique, including cedar, cherry, and plywood faced with types of wood that have a more pronounced woodgrain, such as shina (basswood), katsuragi (katsura), yanagi (willow), or keyaki (zelkova). To make the print, slightly dampened paper is lightly laid over the prepared block, and pressure is applied from the back to transfer the woodgrain pattern onto the paper.

Saitō has signed this work using the Euro-American order of his name in Latin characters rather than the traditional Japanese order of family name followed by given name, written in kanji characters. This method of signing was customary among Japanese artists trained in Western-style painting, as Saitō and many of his sōsaku hanga contemporaries had been. Saitō’s signature varied over his career, but this example, with the triangular “S” and “y,” became standardized in the 1950s. Above his name, Saitō has applied his seal, which bears the character of his given name, 清 (Kiyoshi).