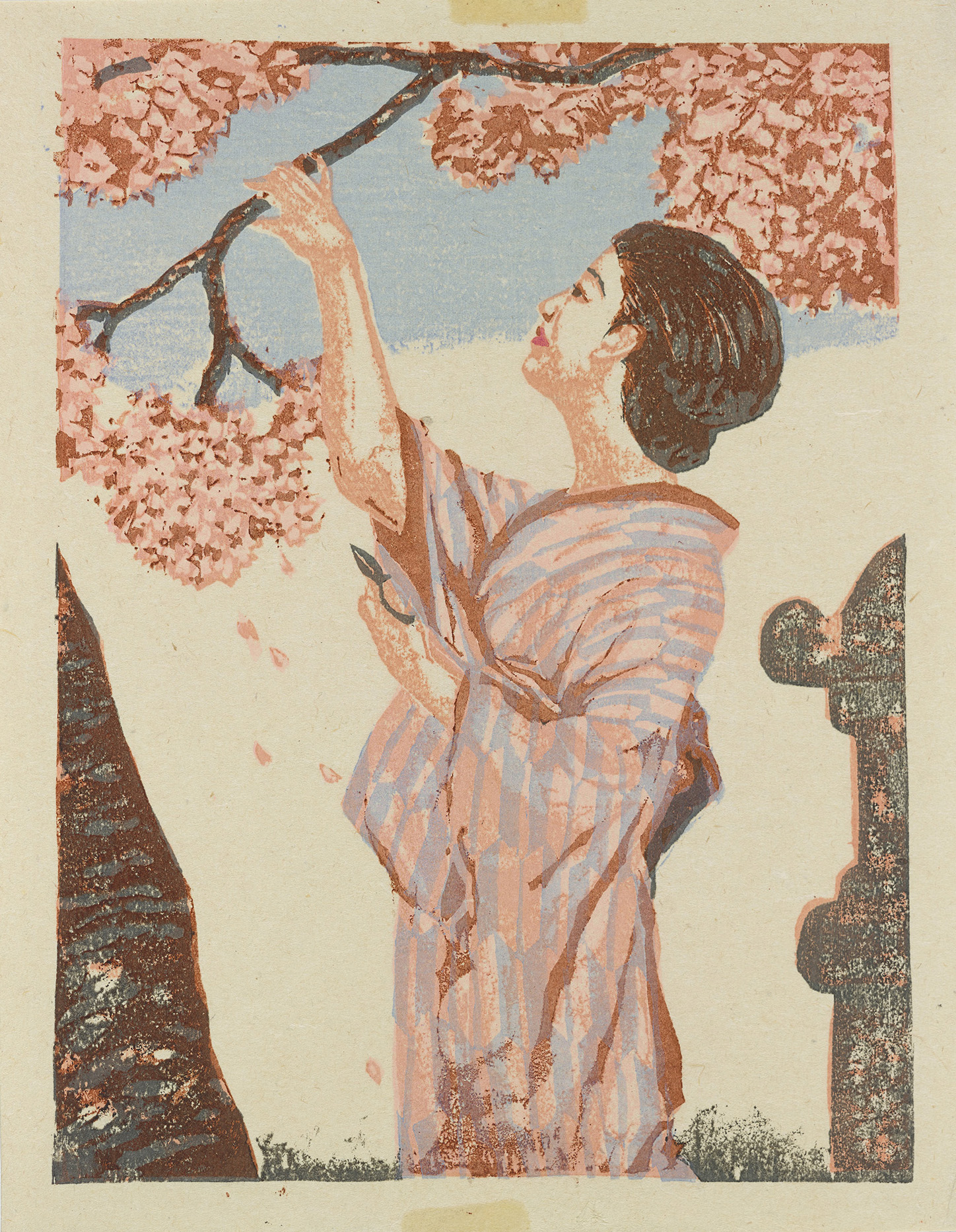

Cherry blossoms have held many meanings in Japanese culture. Blooming for a short period in spring, they have often been symbolic of female beauty, which is misogynistically characterized as similarly short lived and occurring in a woman’s youth, or the “spring” of her life. The association between cherry blossoms and youthfulness also suggests vitality, while their short bloom conjures ideas about the inevitability of death. For this reason, the cherry blossom has also been used as a metaphor for soldiers, including samurai as well as kamikaze pilots in World War II, who painted cherry blossoms on their planes. Cherry blossoms can also symbolize Japan itself. For example, the diplomatic gift of Japanese cherry trees to Washington, DC, in 1912 is one example of how the cherry tree has become emblematic of Japan, and cherry trees across the United States have been vandalized during periods of anti-Asian and anti-Japanese sentiment.

The complex symbolism of cherry blossoms in this image is reflected by the differences in the English and Japanese texts that accompany the work in the portfolio. The English states:

In Japan, cherry blossoms are the symbol of the height of Spring. Although the chrysanthemum is the national flower, the cherry blossoms are more widely known and it has become an annual custome [sic] to visit the parts noted for their cherry blossoms. The artist had intended to make the cherry blossoms in this private garden the subject of his picture, but when the lady come [sic] down to cut a branch for an Ikebana (flower arrangement) he was struck by the effect of her dress under the blossoms.

It also includes the poem “Cherry Trees in April” by the American poet Janet B. Montgomery McGovern (1874–1938) from her book Butterflies of Taiwan, and other Fantasies (1924):

Cherry Trees in April

As the branches of cherry trees in April

Are broken beneath the weight of blossoms,

So is my body broken beneath weight of my love Is my love

like the blossoms here, Without perfume and without promise of fruit

Then may frail body break

Before the blossominy [sic] time is past.

The Japanese text is slightly different and more somber. It concludes with:

The brightness of the cherry blossom season is at the same time heavy and melancholic. Avoiding the bustle of the flower-viewing scene, I chose [to enjoy] the blossoms from within this quiet abode.

Translation appears in Laura Allen, “The Most Superior Association of Engravers: Sosaku Hanga Artists and the Rebuilding of Post-War Japan.” Orientations 42, no. 7 (2011): 82.

枝もたわはな櫻の花、この薄色の花々がさき盛るときは不思議に庭が重く暗くなる。作者言の代りに丁度見つけた知らぬ英國の一女流詩人の時を持って來よう。題は四月の櫻樹 「臺灣の蝶々、その他の夢想」といふ詩集から、

櫻の枝は春四月 花の重さにぞ折れにけり、 わが身また愛の重さにつひえなむ。 わが愛のこの花にかも似む 實らむ契りと行末のなくて、 さらばよわが脆き身のつひえ果てなむ 花時の過ぎぬ間に。

二十年以上もまへの詩集だから、こういふ感慨にもならうか。花時はうつうつと重たい明るさでもある。花見風態の賑はひを避けてこの静かな屋敷内の花盛りを選んだ。

While Onchi produced artworks in support of the war, his son was killed in action in August 1945. Onchi doubtlessly had complex feelings in the wake of this loss, Japan’s defeat, the Allied occupation of Japan, resource scarcity in the immediate postwar period, and the prospect of peace after a long period of militarism. As a symbol, the cherry blossom can encompass all of these—sometimes contradictory—emotions and thoughts.

In late nineteenth century Japan women became signifiers of Japanese traditions and culture. This nationalist narrative emerged in the Meiji period (1868–1912), when Japanese society dramatically transformed into an industrial nation-state, capable of competing militarily and economically with Euro-American powers. In the wake of these changes, which included the adoption of numerous Euro-American technologies, institutions, and ideas, there was significant social anxiety about preserving customs native to Japan. As a solution, conceptions of men’s and women’s roles were reconfigured to one where men were tasked with the modern, foreign, and public spheres, while women were asked to safeguard the traditional, Japanese, and private spheres. Women continued to be treated as symbols of Japanese traditions during and after World War II. Here, Onchi used the female figure to communicate the stability of continuity after a period of intense change.

Members of the Allied occupation forces stationed in Japan comprised an important audience for this print. Occupation personnel were instrumental in the popularization of sōsaku hanga, which they appreciated as both souvenirs and fine art. Indeed, the Americans James A. Michener and Oliver Statler became great patrons to numerous Japanese printmakers and helped promote sōsaku hanga in the US through publications like Michener’s The Modern Japanese Print and Statler’s Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn.

Some images in the portfolio are subtly sexually suggestive. Here, the intimate glimpse of the woman’s elbow, exposed as she reaches for the cherry blossoms, adds a degree of sensuality to the composition. The print was produced at a time when the sexualization and exoticization of Japanese women in American culture was particularly prevalent. The marketing of these printed images of traditionally clothed women to an American audience, while appearing innocuous, was undoubtedly informed by Euro-American stereotypes of Japanese women that were in circulation at this time. Michener, for example, wrote the novel Sayonara (1954), an Orientalist fantasy about an American soldier who falls in love with a Japanese woman, only to abandon her when he returns to America.