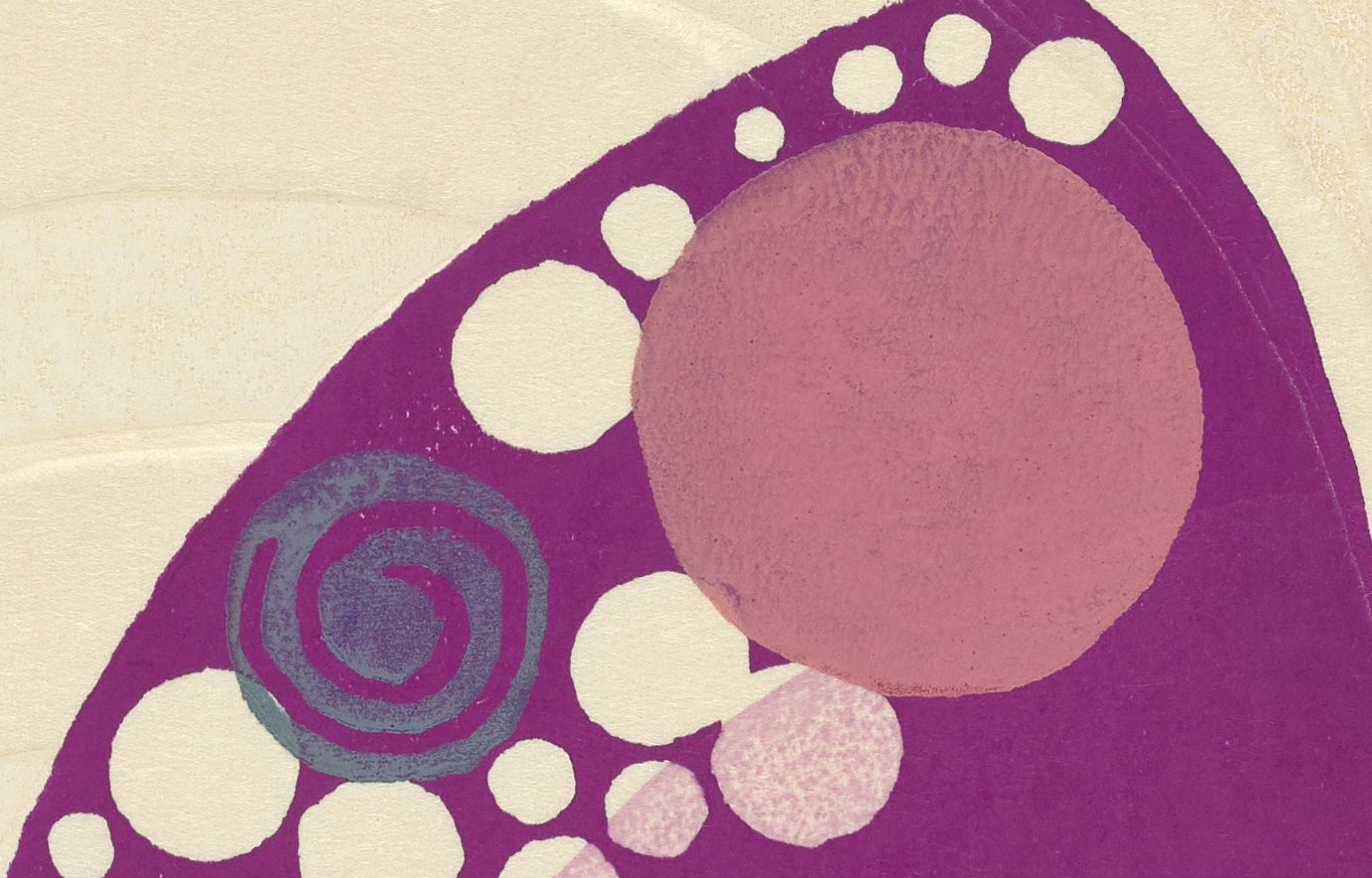

Yoshida deeply embossed this print with a wave-like pattern that creates a pronounced sculptural effect within a conventionally two-dimensional medium. Embossing is the process of creating raised surfaces in paper by applying pressure. She used a modeling spatula to apply pressure by hand. Yoshida emphasized the three-dimensionality of her print by adding a textured white pigment to the recessed surfaces of the paper.

This print features many circular motifs commonly found in Yoshida’s abstract work from this period. She repeated these shapes to find variety in similar forms. The large black circle with uneven edges used once in this print gets repeated in different colors and sizes in Yoshida’s Crystal Clear (1966) (S2019.3.2017). This motif, along with the spiral forms, can also be found in Spiral (1966) (S2019.3.2022).

According to the annotation, this print is impression eleven from a total edition of fifty, but the impression number does not necessarily reflect the order the prints were made. Although the design and materials used to create each impression are usually the same, numerous variables, such as the amount of pressure and pigment applied to each block, can create slightly different and unique works of art. Adding to this complexity, Yoshida often used non-traditional materials, such as string, which introduced greater variation into her printing practice. Many sōsaku hanga artists refined their initial designs through experimentation during the printing process, which meant that even if an edition of fifty was originally planned, they sometimes stopped producing impressions much earlier once they were satisfied with the final product. For that reason, even when a print lists the edition number, the actual edition size can be different.

Yoshida titled this work Awa, the Japanese term for “bubbles” or “foam.” The wave-like embossing and the repetition of small circular shapes evoke bubbly sea foam without attempting to emulate it in any photorealistic sense. Yoshida was also inspired by the soap bubbles in her kitchen sink. Still, the work is non-figurative, an example of the pure abstraction that came into vogue in Japan’s postwar era.

Yoshida was known for her bright color palettes, which she achieved with newly available synthetic pigments made by the NICKER company, founded in 1950. Unlike traditional pigments, the particles in NICKER paints were coarse and remained on the surface of the washi paper instead of penetrating into it, allowing Yoshida to get the strong colors she preferred. According to her daughter, the printmaker Yoshida Ayomi, Chizuko was unique in her use of these pigments and did not worry about the so-called “rules” of traditional printmaking. Instead, she always chose what she liked best.