Light microscopy methods allowed us to study minute samples removed from the sculptures. Using known materials for comparison, we could identify unknown substances.

Reflected and transmitted light magnified features of the materials as much as one hundred times. More specialized microscopy techniques that use polarized and ultraviolet light enabled us to identify textile fibers, lacquer layers, lacquer inclusions, and pigments. For example, we now know that the textile is hemp.

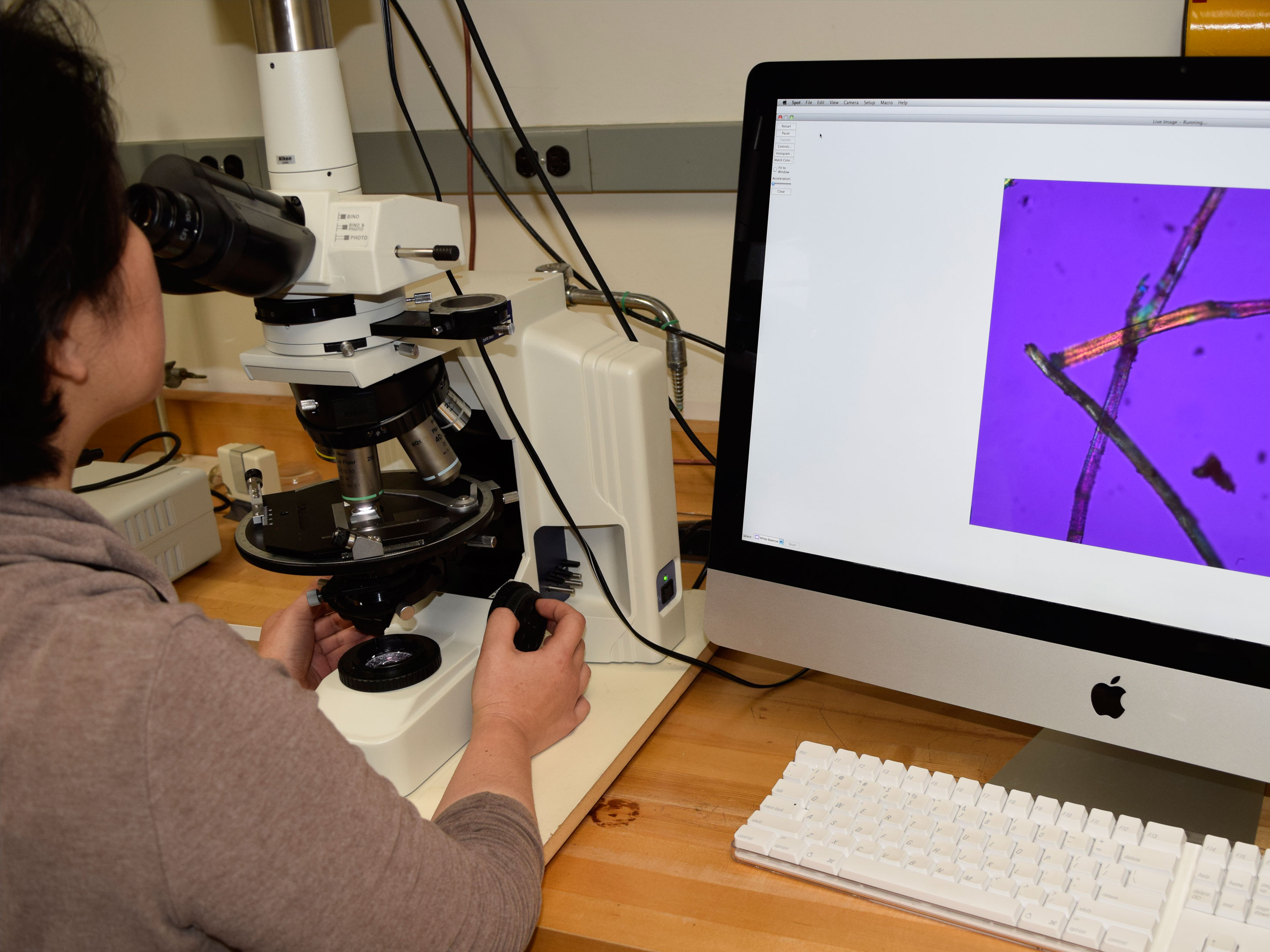

Here, a scientist identifies textile fibers under the polarized light microscope.

Image by Donna Strahan, Freer|Sackler

Looking below the surface reveals the sculptures’ complexity. Resembling a chocolate layer cake, this is a magnified cross section of the layers of lacquer and textile in the Walters Buddha, magnified hundreds of times. Each layer is identified, from the textile at bottom to the paint at top.

Image by Blythe McCarthy, Freer Sackler and Molly McGath, Heritage Science for Conservation, JHU

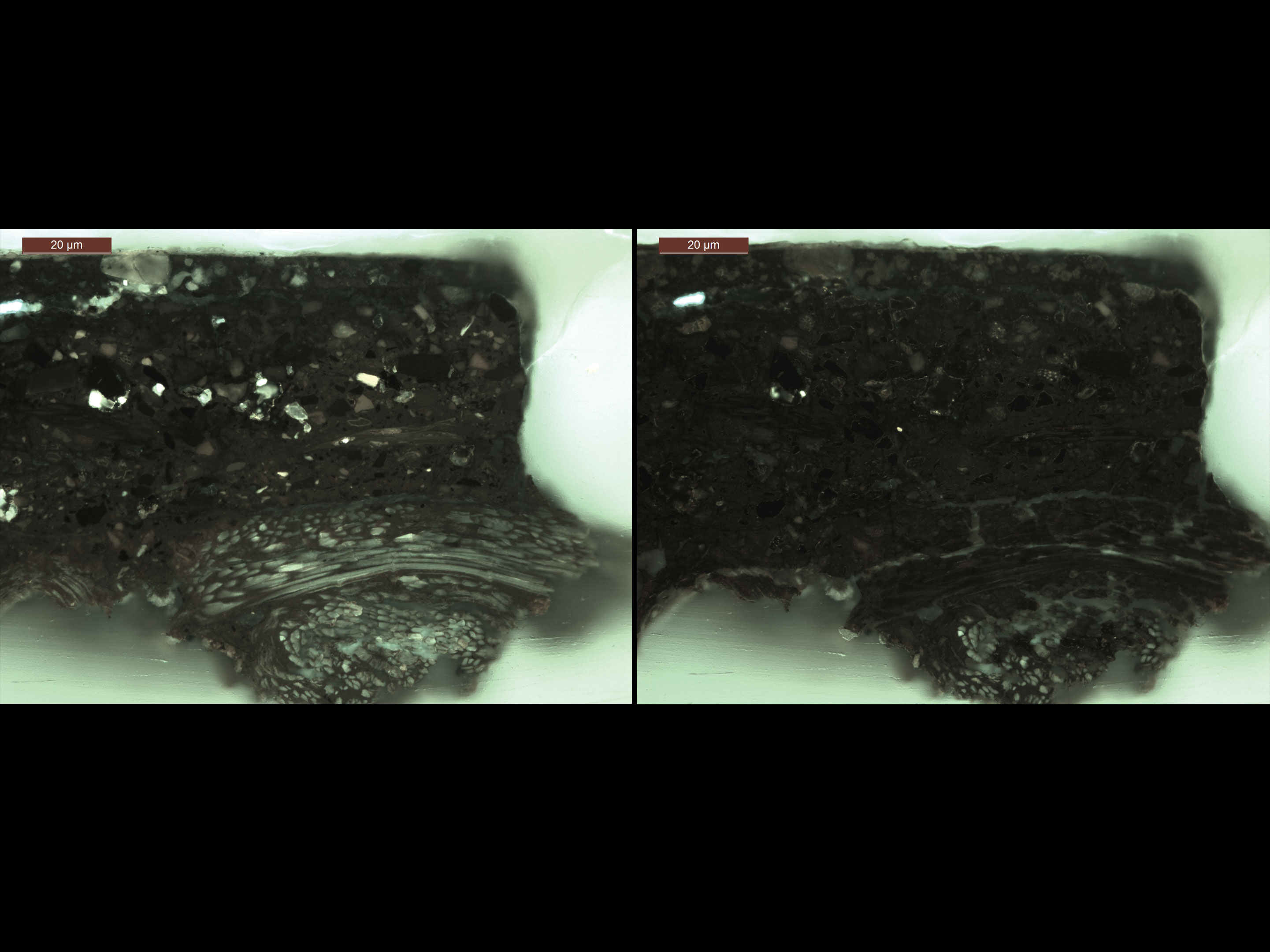

Stains helped us identify materials in the samples when viewed under visible and ultraviolet light. Filters block most of the light, limiting it to wavelengths that cause certain materials to fluoresce.

Left: Freer buddha cross section, unstained. Right: Freer buddha cross section, stained for starch, which darkened those fibers

Images by Blythe McCarthy, Freer|Sackler

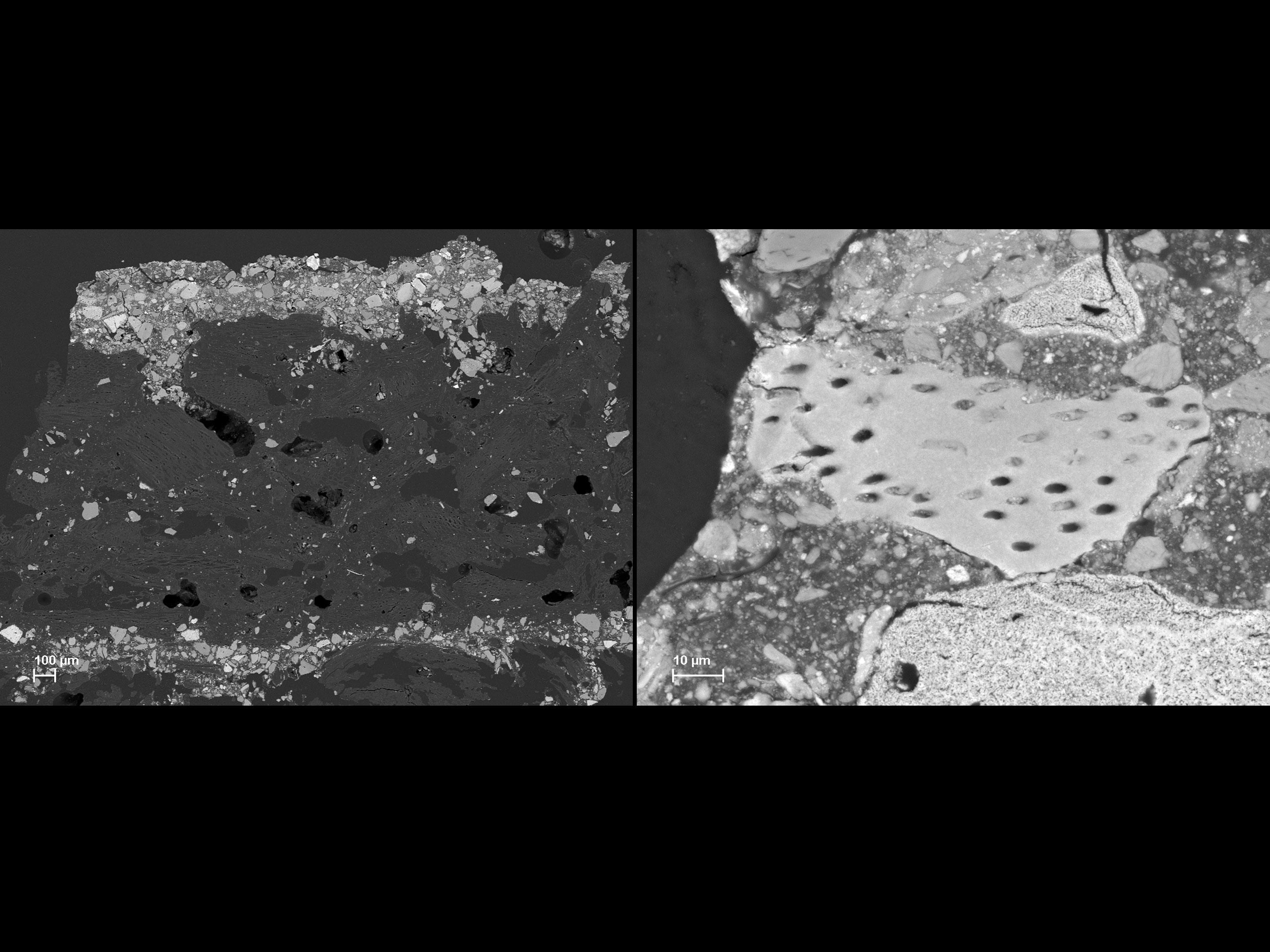

Scanning electron microscopy provides magnification far beyond that attainable with a light microscope. When we equipped the microscope with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, we could identify individual elements.

The image on the left is a cross section of the Metropolitan buddha, revealing textile and lacquer layers. Crushed bone particles (in white) are present throughout the lacquer layers.

On the right, one bone particle has been magnified 930 times. Blood vessel holes penetrate throughout the particle.

Images by Federico Carò, Scientific Research Department, Metropolitan Museum of Art

X-radiography and computed tomography (CT) scans revealed the layers that make up the sculptures, helping us study their construction, joining methods, repairs, and other internal features. The objects were X-rayed while a device scanned them to produce many X-ray sections or slices. A computer then assembled the information into an X-ray reconstruction of the object’s interior. The X-radiographs confirmed that the top of the head on three sculptures was attached separately, providing access to install the eyes from the inside.

In this image, the Freer buddha enters the instrument for CT scanning at the National Museum of Natural History.

Image by Hutomo Wicaksono, Freer|Sackler

X-ray fluorescence analysis is based on the principle that individual atoms, when excited by an external energy source, emit X-ray photons of a characteristic energy or wavelength. By counting the number of photons of each energy emitted from a sample, we could identify the elements present, such as calcium, lead, or copper.

Here, a scientist and conservator perform X-ray fluorescence analysis to determine the elements in the sculpture’s eye.

Image by Emily Jacobson, Freer|Sackler

Pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectroscopy (py-GCMS) helped us identify the organic components mixed in each lacquer layer, such as oils and starches. A minute sample was heated until it decomposed, producing smaller molecules that could then be separated and detected. We discovered blood was mixed in with some of the lacquer, and we determined which tree species the lacquer came from.

Here, a scientist puts a minute sample into the pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometer for organic analysis.

Proteomics, a field of molecular biology that studies proteins in organisms, allowed us to identify the species of the ground bone mixed into the lacquer. The bone’s proteins were broken up into their component peptides. Then, we compared the peptides’ molecular weight—together with the sequences of amino acids that they contain—to databases of known protein sequences. We now know that the bone in one of the sculptures is equine, meaning it came from a horse, and another is bovine, or from a cow.

In this image, a conservator samples the bodhisattva for protein analysis.

Images by Blythe McCarthy, Freer|Sackler