National Museum of Asian Art Announces Its 2024 Lunar New Year Family Festival

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art has announced its 2024 family festival commemorating Lunar New Year, a celebration of the arrival of spring and the beginning of a new year on the lunisolar calendar. The event takes place Feb. 3, 11 a.m.–4 p.m. It is free and open to the public.

This year’s Lunar New Year festival will celebrate the year of the dragon. It will consist of performances, talks, tours, hands-on activities and more. The full schedule is available online. The museum also offers many resources to learn about Lunar New Year on its website such as virtual tours of related collections, lesson plans and webinars.

The National Museum of Asian Art began its centennial year in January 2023 with a Lunar New Year festival attended by more than 6,500 people with another 700 joining a lion dance performance on the Freer Plaza.

The 2024 event is copresented by the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China, Vietnam Society and the Korean Cultural Center Washington, D.C.

About Lunar New Year

Commonly known as the Spring Festival in China, Lunar New Year is a 15-day celebration marked by many traditions. The Lunar New Year’s Eve reunion dinner is the highlight that kicks off the holiday, a feast with a spread of symbolic dishes, such as a whole fish representing abundance, that bring good luck and fortune. The 15th and final day of the holiday is the Lantern Festival, during which people have tangyuan, or sweet glutinous rice balls, and children carry lanterns around the neighborhood at night to mark the end of the celebration.

In the Chinese zodiac, 2024 is the year of the dragon. Different regions across Asia celebrate Lunar New Year in many ways and may follow a different zodiac. Many Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders do not observe the Chinese/lunar zodiac.

About the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art is committed to preserving, exhibiting, researching and interpreting art in ways that deepen our collective understanding of Asia, the United States and the world. Home to more than 46,000 objects, the museum stewards one of North America’s largest and most comprehensive collections of Asian art, with works dating from antiquity to the present from China, Japan, Korea, South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Islamic world. Its rich holdings bring the arts of Asia into direct dialogue with an important collection of 19th- and early 20th-century art from the United States, providing an essential platform for creative collaboration and cultural exchange between the U.S., Asia and the Middle East.

Beginning with a 1906 gift that paved the way for the museum’s opening in 1923, the National Museum of Asian Art is a leading resource for visitors, students and scholars in the United States and internationally. Its galleries, laboratories, archives and library are located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and are part of the world’s largest museum complex, which typically reports more than 27 million visits each year. The museum is free and open to the public 364 days a year (closed Dec. 25), making its exhibitions, programs, learning opportunities and digital initiatives accessible to global audiences.

National Museum of Asian Art Announces Major Gift of Archival Records From J.T. Tai & Co., an Influential 20th-Century Dealer of Chinese Art

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art has announced a major gift of inventory records of J.T. Tai & Co., an important dealer of Chinese antiquities who shaped American collections of Chinese art throughout the second half of the 20th century. J.T. Tai (1911–1992), owner of the company, was the first to donate objects to the Center for Asian Art of the Smithsonian Institution, now part of the National Museum of Asian Art. Victoria W. Hsu, secretary of the board of directors at the J.T. Tai & Co. Foundation, and other board members acted on behalf of the late Tai, generously presenting J.T. Tai & Co.’s inventory records to the National Museum of Asian Art during the museum’s centennial celebrations.

Researching and documenting provenance—the history of an object’s ownership, from its creation to the present—are core activities of the National Museum of Asian Art, and the museum’s team of four full-time provenance researchers is an unprecedented number for a museum of its size. Their work animates the museum’s strategic plan goals: to expand, preserve and celebrate its collections; to identify, attract and serve new and diverse audiences through both its physical and digital spaces; to foster an object-inspired understanding of the arts, communities, cultures and societies of Asia; and to build a museum culture that is creative, collaborative, transparent and resourceful. The addition of this material contributes to the museum’s ongoing portfolio of provenance research, which includes convening the first major symposium on Asian art provenance research.

With this new gift, the museum’s archives now include more than 165 archival collections that it makes available to experts around the world. The J.T. Tai & Co. archive will significantly impact the knowledge of the art market of Chinese objects in the United States. The museum will digitize the documents and make them available to researchers, allowing unprecedented access to information on objects sold through the company. This landmark acquisition will provide provenance researchers at museums across the country (and globally) the tools to answer questions about their collections’ history that formerly remained ambiguous or unsolved.

Tai operated his business in New York City from 1950 until shortly before his death in 1992. J.T. Tai & Co. and Tai himself immensely influenced the development of several important American collections of Asian Art; Tai ranks second only to fellow dealer C.T. Loo in his impact on advising institutions and scholars alike.

“I could not be more pleased to announce that our museum has just been given an extraordinary gift of documents,” said Chase F. Robinson, the museum’s director. “J.T. Tai was a leading international dealer of Chinese objects. Thousands of works of art passed through his company and populated the leading private and museum collections in the West. That’s why the inventory records of J.T. Tai & Co. are something of a holy grail for provenance research, offering unique documentation for object histories.”

Joanna M. Gohmann, the museum’s provenance researcher and object historian, and J. Keith Wilson, curator of ancient Chinese art, made several visits to the collection to study the documents and history of the company.

“This incredible archival collection will propel research into the provenance history of Asian art,” Gohmann said. “These documents will transform our understanding of collecting Chinese art in America. They reveal an intricate, international network of dealers and collectors. There is so much to discover and so many histories to share!”

About J.T. Tai

Tai (née Dai Fubao and later styled with the courtesy name Runzhai; he adopted the moniker J.T. Tai when he immigrated to the United States) began his career at his uncle’s small antique store in Wuxi, China, and later moved onto cosmopolitan Shanghai, where he opened his own store Fuyuanzhai guwandian. Between 1945 and 1949, Tai regularly sold antiquities sourced in China to Loo, who in turn sold them to Western clients in Paris, London and New York. Upon the establishment of The People’s Republic of China, Tai fled his homeland and found refuge in Hong Kong. In early 1950, Tai immigrated to New York City with the help of Loo.

About J.T. Tai & Co.

The Aug. 21, 1950, edition of The New York Times announced the grand opening of Tai’s Madison Avenue gallery, J.T. Tai & Co. The National Museum of Asian Art formed a long, enduring relationship with J.T. Tai & Co. acquiring several works of art through the gallery. Tai was deeply invested in making Chinese art visible and accessible. In 1981, Tai and Dr. Fucheng Richard Hsu, president of the China Institute in America (1969–1983), developed a charitable foundation, the J.T. Tai & Co. Foundation, which—to this day—supports higher education and health care.

About the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art is committed to preserving, exhibiting, researching and interpreting art in ways that deepen our collective understanding of Asia, the United States and the world. Home to more than 46,000 objects, the museum stewards one of North America’s largest and most comprehensive collections of Asian art, with works dating from antiquity to the present from China, Japan, Korea, South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Islamic world. Its rich holdings bring the arts of Asia into direct dialogue with an important collection of 19th- and early 20th-century art from the United States, providing an essential platform for creative collaboration and cultural exchange between the U.S., Asia and the Middle East.

Beginning with a 1906 gift that paved the way for the museum’s opening in 1923, the National Museum of Asian Art is a leading resource for visitors, students and scholars in the United States and internationally. Its galleries, laboratories, archives and library are located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and are part of the world’s largest museum complex, which typically reports more than 27 million visits each year. The museum is free and open to the public 364 days a year (closed Dec. 25), making its exhibitions, programs, learning opportunities and digital initiatives accessible to global audiences.

Accounting for Art

Charles Lang Freer’s Art Vouchers

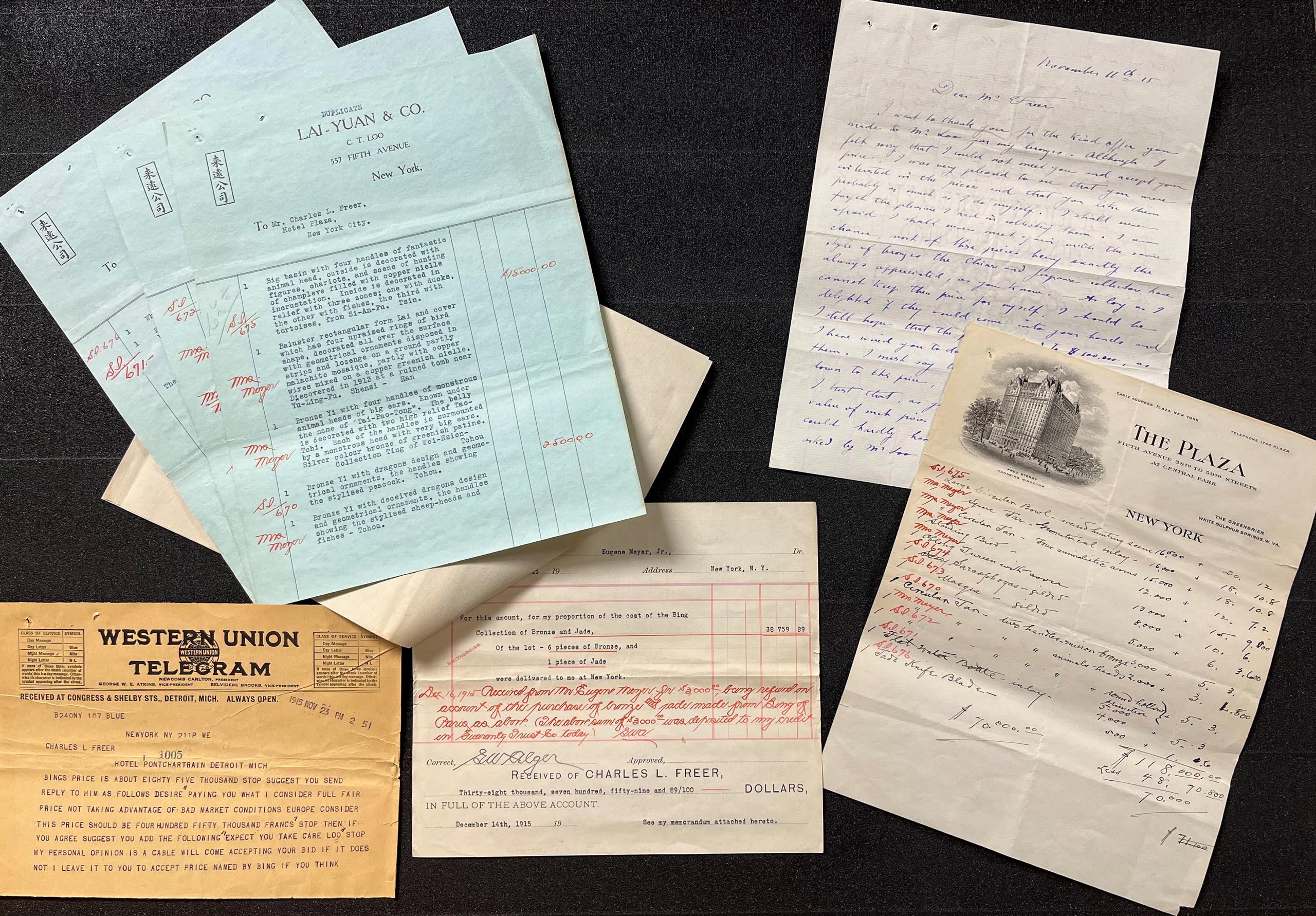

In 1893, Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919) began implementing the voucher system, an accounts-payable process developed in the late nineteenth century that was widely adopted by large corporations, to manage purchases of artworks and other expenses related to his renowned collection of Asian and American art. As a former accountant for the New York, Kingston, and Syracuse Railroad Company and then an owner and executive of the Peninsular Car Company, Freer had experience managing finances, so it comes as no surprise that he maintained impeccable financial records for his collection. The voucher system allowed Freer, the litany of clerks affiliated with the banks he patronized, and his private accountants to track his many purchases from the moment the collector identified something to buy to the moment vendors debited his accounts. Today, these records are preserved in the National Museum of Asian Art Archives and allow researchers to study not only Freer’s personal collecting practices but also several other facets of art history and daily life at the turn of the century.

A voucher is a document that confirms a business transaction is truthful. The voucher system uses individual records to organize outgoing expenses, grouping all documents related to a singular purchase and indexing the information found on those documents. Freer’s vouchers, measuring roughly seven-by-eight inches, were designed to fold in half to contain purchasing paperwork, including correspondence from dealers and other vendors, provenance documentation, photographs, publications related to works of art, and invoices. Emblazoned with “C. L. Freer” in bold lettering, each voucher provided a place for the accountant to record the purchase price and month of purchase and to describe the transaction. The accountant would also record the date of payment and the corresponding check number and note where one could locate the debit recorded in Freer’s central voucher registration book in which all outgoing payments were recorded.

Accountants would track the progress of a purchase on the interior of the voucher. After recording the arrival date of the invoice and itemizing the proposed purchase, the accountant signed in approval and then presented the voucher and its accompanying paperwork to Freer. It seems that at this stage Freer annotated the voucher and its contents, identifying where he wanted objects to go: his home, to a friend, or, after 1903, directly to the Smithsonian Institution. Upon Freer’s approval, accountants issued a check, which they sent to the vendor along with the voucher itself. Upon deposit, the vendor signed, dated, and returned the voucher to Freer’s home in Detroit, where clerks filed it for reference.1

While the vouchers themselves offer great insight into financial practices at the turn of the century, the documents that accompany them are vital to understanding the global art market at the time. Freer made purchases from dealers, fellow collectors, and artists in America, Europe, and Asia whom he met during his travels. When Freer’s health began to fail in the early 1900s, vendors frequently sent large crates of artworks to his Detroit home, allowing him to select wares comfortably and at a leisurely pace. Dealers often sent Freer more than he requested for purchase, hoping something else would catch the famed collector’s eye. Through the voucher documents, researchers can reconstruct an object’s journey across the globe and discover the histories of not only the objects that Freer acquired but also those he turned down. Freer routinely annotated the invoices and letters that were filed with the final vouchers, noting which works to gift to friends, striking through objects to return, and listing features of certain objects that appealed to him. Researchers can explore how Freer negotiated prices, demonstrated a preference for particular types of works, and developed his ideas about taste and aesthetics. For example, the annotations on a November 26, 1904, invoice from Yamanaka & Company highlight Freer’s fascination with color and saturation. Next to the dealer’s object descriptions, Freer noted the “brilliant colors” in a kakemono (F1904.340a–h) and “the chocolate-colored glaze with an overflow of dark brownish red and orange” on an Edo-period rooster ewer (F1904.331a–b).2

Freer’s voucher collection provides a sense of how World War I (1914–18) shifted the art market from Paris to New York. European dealers and collectors hurriedly sold collections for lower prices as sales were increasingly directed through New York galleries, where Americans were enthusiastically buying. For example, the documentation created in 1915 for a collection of important Chinese bronzes and a jade (F1915.102, F1915.103a–b, F1915.104, F1915.105, F1915.106a–f, F1915.107, F1915.108, F1961.30a–b, F1961.31a–b, F1961.32a–b, F1968.28 and F1968.29) from the jeweler and art dealer Marcel Bing (1875–1920), brokered by C. T. Loo (1880–1957) through his New York gallery, Lai-Yuen & Co., illustrates this market shift and highlights the American economic advantage. In a letter to Freer explaining his refusal to further discount the bronzes, Bing laments that “[he] should not desire [to] come down to this [previously identified] price, had circumstances been as usual.”3 The war’s impact on global economics led the value of the United States dollar to skyrocket and presented Americans with an opportunity to compete with European elites more boldly in the purchase of fine art. Freer and his friends and fellow collectors Eugene and Agnes Meyer (1875–1959; 1887–1970), with whom he purchased the group of bronzes, therefore secured the works for a competitive price by paying in francs.4

The vouchers and documents also provide an opportunity to trace the evolution of how the West studied Asian works of art. Correspondence pertaining to acquisitions between Freer, the dealer Bunkio Matsuki (1867–1940), and the intellectuals Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) and Edward S. Morse (1838–1925) reveal how the early study of Chinese and Japanese ceramics depended upon art historical comparisons of objects. Dealer invoices and letters contain words and phrases used to identify types of glazes, painting techniques, and bronze patinas and illustrate how those classifications evolved. Freer often sought works of art by named artists. The correspondence and annotations on dealer invoices reflect his desire to know details about craftsmen and his growing knowledge of the works in his collection as well as improvements in his ability to identify styles and artists.

When Freer began to consider giving his collection to the Smithsonian Institution around 1902, he and his accountants retroactively applied the voucher system to his earlier art purchases, thereby organizing all acquisition information for nearly his entire collection.5 It is unclear what exactly drove this decision; however, it is clear that Freer saw this resource as indispensable information. Before his death, Freer reserved all the vouchers and the documents they enclosed for transfer to the Smithsonian, where they have been located since 1920. Freer and his contemporaries surely understood the materials’ practical importance in transferring ownership of the collection, but did the group also have the foresight to consider them invaluable assets for future scholars? Indeed, this trove of primary sources proves significant to advancing knowledge of not only the history of Charles Lang Freer’s renowned collection but also financial management, the global art market in the early twentieth century, histories of collecting and taste, and the understanding of Asian art in the West.

History

Ars Orientalis is a joint publication of the Freer Gallery of Art and University of Michigan’s History of Art Department. The journal originated from the ideals of two visionary men: Charles Lang Freer, the Detroit industrialist who donated the art collection that formed the Freer Gallery of Art, and Mehmet Ağa-Oğlu, a Near Eastern art curator at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) and the first professor of Islamic art in the United States at the University of Michigan (UM).

The journal was launched under UM’s auspices as Ars Islamica (1934–51). Ağa-Oğlu, who began serving as Near Eastern curator at the DIA in 1929, held a dual appointment at UM in summer 1932 as the Freer fellow and lecturer of Oriental art. This setup, made possible by Charles Lang Freer’s financial support of UM, facilitated collaboration between the museum and the university—benefitting both institutions as well as the students—and helped the DIA survive the Depression without losing its expert staff.

Ağa-Oğlu soon created a robust program of Islamic art, officially recognized as the Research Seminary of Islamic Art. In 1933, he proposed his plan to publish a journal solely dedicated to the study of Islamic art. The idea found support at the university, especially from president Alexander G. Ruthven. Among Ağa-Oğlu’s many efforts to establish Islamic art as an academic discipline, the creation of Ars Islamic may be the most enduring one.

The journal initially appeared as a collaboration between the DIA and UM, and the financial support came from UM’s Freer Research and Publication fund. In the inaugural volume, released in January 1934, Ağa-Oğlu as the founder and editor explained the vision for Ars Islamica:

Ars Islamica appears at a time of universal economic disorder, which affects severely our material and spiritual existence, but it hopes in spite of all difficulties to be of some service to contemporary culture by enlarging knowledge in the field of Islamic Art. Its success in this responsible work depends wholly on the cooperation of scholars and on the support of learned institutions and the art-loving public.

Ağa-Oğlu described the journal’s principal aim as promoting an interest in the study of Islamic art by creating “an academic arena for the discussion of various problems concerning the historical and artistic development of the arts and crafts in Islamic countries.” In addition, he wrote:

The magazine, it may be noted, will take a neutral position and will not represent or support any one point of view. Its pages will be open to comments on problematic questions interpreted from contrasted points of view, since the publishers are of the opinion that only by following this policy can the magazine be of service in advancing its cause.

From the very first issue, Ars Islamica was well received by scholars around the world. By 1935, it had been reviewed in many prestigious publications of the time—such as The Bulletin of the American Institute for Persian Art and Archaeology, Artibus Asiae, New York Times, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, and Bulletin de l’Office international des instituts d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’art—as a serious academic undertaking.

The University of Michigan took full responsibility for publishing the journal from the second issue onward. One of the highlights from the early years of Ars Islamica is the issue published on UM’s hundredth anniversary in 1937. This special volume had thirty-five articles, authored by scholars representing fourteen different countries, thus showcasing the journal’s aptitude for bringing together international scholars and supporting diversity in the field.

At the time, the journal had a consultative committee composed of scholars from different countries, as well as from different (but related) fields in art history. The Islamic art scholars serving on the committee included Maurice Dimand, Halil Edhem Eldem, Ernst Herzfeld, Rudolf Meyer Riefstahl, Friedrich Sarre, Josef Strzygowski, Laurence Binyon, Albert Gabriel, Ernst Kühnel, and Gaston Wiet. Scholars from related fields included John G. Winter, professor of Latin and head of UM’s division of fine arts; Alexander G. Ruthven, UM president and professor of zoology; Ananda Coomaraswamy, a prominent scholar of Indian art; John E. Lodge, director of the Freer Gallery and an expert on Japanese and Chinese art; and William Valentiner, director of the DIA and an expert on Dutch art.

Ağa-Oğlu served as editor of the journal until 1937. The position was subsequently filled by another pioneering figure in Islamic art, Richard Ettinghausen, who upheld the journal’s high scholarly standards and international scope. The political climate of the era, however, inevitably had an impact on Ars Islamica. Evaluating the first ten years of the journal in its 1944 volume, John Winter, director of UM’s division of fine arts, recalled the struggle to maintain the journal’s international character during World War II. Communication with authors abroad was delayed and sometimes lost completely, which in turn delayed or halted publication. Indeed, while Ars Islamica was published twice annually from 1934 to 1941, it appeared once a year from 1941 to 1943 and then intermittently until its final volume was released in 1951. That issue announced that the journal’s name would be changed to Ars Orientalis and it would now cover the arts of the entire Asian continent.

The shift was never intended as a total breakaway from the founding principles of Ars Islamica. In his announcement of the plans for Ars Orientalis, Ettinghausen referred to the rising cost of printing and the increase in article submissions (due to the suspension of scholarly publications in Europe) as the two major obstacles to maintaining Ars Islamica in its established form. Along with broadening its scope, Ars Orientalis would differ from its predecessor, which was published on a fixed schedule, by being published as soon as the appropriate materials were brought together.

By 1951, Ettinghausen had resigned from his position at UM and become the associate curator of Near Eastern art at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC—bringing the journal’s editorial offices along with him. The Freer Gallery of Art joined the University of Michigan in publishing Ars Orientalis, a partnership that continues to this day. The collaboration was legitimized by article twenty-four of Charles Lang Freer’s will (1918), which states:

The proceeds from the bequest to the University of Michigan shall be used to add to the knowledge and appreciation of Oriental Art. Said income shall be used primarily in aid of research to be conducted by experts regarding the art objects embraced in the collection of Oriental Art transferred or bequeathed by me to the Smithsonian Institution; for the publication of results of such research, and for the preparation of text of descriptive scientific catalogues of said collections whenever the necessary information can be prepared.

The first volume of Ars Orientalis was published in 1954, with Ettinghausen as the Near Eastern art editor and Max Loehr, a distinguished Chinese art professor at UM, as the editor of Far Eastern art. This editorial setup continued for only two volumes: Oleg Grabar took over as editor of Near Eastern art beginning with the third issue. Grabar also took over the position of UM professor of Islamic art that Ettinghausen had left vacant, and the Ars Orientalis editorial offices moved back to the university. In the first volume he edited, Grabar published his seminal piece “Umayyad Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem,” which had a lasting impact on the field and remains the most accessed article in the journal’s history. With volume 3, the journal also returned to the editorial structure of Ars Islamica, with a consultative committee composed of scholars including Archibald Wenley, Norman W. Brown, Alexander B. Griswold, John D. Cooney, George C. Miles, Laurence Sickman, Antoinette K. Gordon, Alexander C. Spur, and Ettinghausen.

Volume 4 (1961) included nine articles dealing with Far Eastern art and eight dealing with the Near Eastern art. With a few exceptions, the subsequent issues of Ars Orientalis have reflected a geographic balance in their contents and covered the whole of Asia.

Beginning with volume 5 (1963), the editorial structure of the journal shifted from individual editors assigned to specific fields to a board of editors, composed of members from both the Freer and UM. Standout articles from the 1960s and 1970s include James Cahill’s “Yuan Chiang and His School” (1963, 1966); Esin Atil’s “Ottoman Miniature Painting under Sultan Mehmed II” (1973); Barbara Keyser’s “Decor Replication in Two Late Chou Chien” (1979); and Helmut Brinker’s “Shussan Shaka in Song and Yüan Painting” (1973). The journal also included book reviews, in-memoriam pieces, notes, and announcements, as Ars Islamica had done.

A special issue on the technical study and conservation of artworks from Asia (vol. 11, 1979) also launched a new phase in the journal’s history, referred to as the “new Ars Orientalis” by its publishers. Largely to reduce printing costs, the journal’s size, number of pages, paper, and binding were modified. These changes in design and production gave the journal the appearance it maintains today in its print version. Around the same time, the Chinese and Japanese Centers at the University of Michigan took over publishing the journal for three years (vols. 12–14); the Freer Gallery and UM’s History of Art Department were named as sponsors. From volume 15 on, UM’s History of Art Department again assumed responsibility for publishing Ars Orientalis.

In the 1980s, editorial duties were shared by an editor, a book review editor, and an editorial committee. Terry Allen (Near Eastern and book review editor), Richard Edwards (Far Eastern editor), and an editorial committee led by Thomas Lawton produced the journal in those years. Highlights of the decade include Yoshiaki Shimizu’s “Seasons and Places in Yamato Landscape and Poetry” (1981); Marianna Shreve Simpson’s “The Production and Patronage of the Haft Aurang by Jami in the Freer Gallery of Art” (1982); Louise Yuhas’s “Lu Chih and the Literati Tradition: Paintings in the Style of Ni Tsan” (1982); Priscilla Soucek’s “The New York Public Library Makhzan al-asrar, and Its Importance” (1988); and Hidemi Kond’s “Shen Nanpin’s Japanese Roots” (1989).

In the 1990s, Ars Orientalis started to publish occasional thematic volumes guest edited by pioneering scholars in their respective fields. The first was a special issue on premodern Islamic palaces guest edited by Gülru Necipoğlu in 1993 (vol. 23). It was followed by another special issue on Chinese painting guest edited by Louise Yuhas, published in honor of Richard Edwards (vol. 25, 1995). Other impactful articles from these years are Stanley Abe’s “Art and Practice in a Fifth-Century Chinese Buddhist Cave Temple” (1990); Peter Sturman’s “Cranes Above Kaifeng” (1990); C. Y. Fu’s “Little Hermitage in the Autumn Woods: A Late Ming Painting by Xiang Dexin Misattributed to Tao Fuchu of the Yuan-Shen” (1995); and James Cahill’s “Some Alternative Sources for Archaistic Elements in the Paintings of Qian Xuan and Zhao Mengfu” (1998).

In 2003, through a new agreement between UM’s History of Art Department and the Freer Gallery, the journal’s editorial offices moved to DC. While the Freer has assumed responsibility for publishing the journal, UM provides financial support and plays a key editorial role through its presence on the board.

Ars Orientalis published thematic volumes more frequently during the 2000s, and in 2011, the journal decided to publish themed volumes only. It now focuses on issues of encounter and interaction as well as conflict and accommodation, and aims to redefine and cross boundaries—both spatial and temporal—in the arts of Asia. Recent volumes include: Exhibiting the Middle East: Collections and Perceptions of Islamic Art (guest edited by Linda Komaroff); Communities and Commodities: Western India and the Indian Ocean, Eleventh to Fifteenth Centuries (guest edited by Alka Patel); Current Directions in Yuan Painting (guest edited by Nancy S. Steinhardt); Theorizing Cross-Cultural Interaction among the Ancient and Early Medieval Mediterranean, Near East, and Asia (guest edited by Matthew P. Canepa); Globalizing Cultures: Art and Mobility in the Eighteenth Century (guest edited by Nebahat Avcıoğlu and Finbarr Barry Flood); and Royal Portrait Photography Across Asia (edited by Nancy Micklewright).

Ars Orientalis celebrated its sixtieth anniversary, and the eightieth year since Ars Islamica was first published, with a bold new step. With volume 44 (2015), on the arts of death in Asia (guest edited by Melia Belli), Ars Orientalis launched its first entirely digital volume in collaboration with UM Publishing. For the first time, we are able to offer Ars Orientalis with innovative online features and tools—just the latest development in the history of this pioneering publication. With the publication of Ars Orientalis 47 (2017), the journal went fully open access.

Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art Announces New Board Appointments: Actress Mindy Kaling and Art Historians June Li and Young Yang Chung

The National Museum of Asian Art has announced the newest appointments to its board of trustees: Mindy Kaling, Emmy-nominated writer, producer, New York Times best-selling author, director and actor; June Li, historian of Asian art and founding curator (emerita) of the Chinese Garden at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens; and Young Yang Chung, textile historian, museum founder and director and embroiderer, who is renewing her appointment for a second term. Each is a pioneer in her field, and all share a common commitment to arts and culture, especially in their power to foster understanding and respect and to celebrate diversity and community. They join at a pivotal moment as the National Museum of Asian Art prepares for its centennial in 2023—a springboard for the museum’s ongoing transformative work to broaden and deepen its impact on site, online and through national and international partnerships.

“The National Museum of Asian Art has a long tradition deeply rooted in the appreciation of Asian arts and history, with iconic objects in our collection that date back thousands of years,” said Chase F. Robinson, the Dame Jillian Sackler Director of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art. “As we enter our centennial year, we’re building on that deep tradition by launching a variety of innovative digital initiatives, public programs and community collaborations, which will help us share Asian arts and cultures with a wide range of audiences. Mindy, June and Young Yang personify these different facets of our museum. It is an honor to have them join our board at this important moment in our history.”

The Smithsonian’s Board of Regents approved their appointment for four-year terms each, effective October 1, 2022. The 17-member board of regents, consisting of the Chief Justice of the United States, the Vice President of the United States, three members of the United States Senate, three members of the United States House of Representatives, and nine citizens, is responsible for the administration of the Smithsonian.

“I want to personally thank Mindy, June and Young Yang for their commitment to the National Museum of Asian Art and the vision and mission we have set forth,” said Antoine van Agtmael, the museum’s board chair. “These new appointees bring the board to 27 elected members, a diverse group of accomplished individuals from around the world who enrich our museum with their unique perspectives. Over the last three years, we have nearly doubled our membership, and never in the museum’s history have we had a larger or more diverse board.”

About the New Members

Mindy Kaling

Emmy-nominated writer, producer, New York Times best-selling author, director, actor, and, most recently a Tony Award winner, Kaling has been named one of the brightest voices of her generation.

At 24, Kaling joined the eight-person writing staff of The Office as the only woman. During her eight seasons, Kaling starred as Kelly Kapoor, wrote 26 episodes (more than any other writer), and became the first woman of color to be nominated for an Emmy in any writing category. Kaling directed two episodes and served as both producer and executive producer on over 120 episodes, earning five consecutive nominations for the Emmy Award for Outstanding Comedy Series.

After signing an overall development deal with Universal Television, Kaling created the The Mindy Project, which she starred in and executive produced. At the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, Kaling premiered her debut screenplay, Late Night. The film received critical acclaim and was sold to Amazon for a record-setting deal.

One of Kaling’s more recent projects is the critically acclaimed series Never Have I Ever for Netflix, which recently wrapped production on its fourth and final season. Kaling is also the co-creator and executive producer of The Sex Lives of College Girls, which had the biggest premiere of any comedy on HBO Max in 2021. Upcoming projects for Kaling include season two of The Sex Lives of College Girls, Legally Blonde 3 and the animated adult-comedy Scooby-Doo prequel Velma.

Kaling has released two New York Times best-selling comedic memoirs and a collection of essays with Amazon. In 2022, Kaling launched a boutique literary line, Mindy’s Book Studio from Amazon, with its first selection, Sonali Dev’s The Vibrant Years, releasing this December.

June Li

Li is curator emerita and founding curator of Liu Fang Yuan, the Garden of Flowing Fragrance, at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California. She began in this role in 2004 to establish the historical and cultural context for the garden while it was being built. She founded a series of educational programs, including lectures, symposiums, exhibitions, and performance arts to highlight Chinese garden culture. Li and her husband, Simon, also established the Center for East Asian Garden Studies at the Huntington. The first phase of the garden opened in 2008, the second in 2014 and completion was in 2020. After Li’s retirement in 2014, she continued as an advisor on Huntington projects, including the garden and curated an exhibition for which she co-authored the catalog “Gardens, Art and Commerce in Chinese Woodblock Prints.”

Li previously worked at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, first as a registrar then as assistant curator. She managed several exhibitions on Chinese art, including two major traveling exhibitions from China (a tomb sculpture show from Chinese museums, “The Quest for Eternity,” 1986–1988, and one on significant paintings from the collections of the Palace Museum in Beijing and the Shanghai Museum, “The Century of Tung Ch’i-Ch’ang,” 1990–1992). She also curated “Paintings of Zhi Yuan: Revisiting a Seventeenth-Century Chinese Garden” in 1995. Li retired as the associate curator of Chinese and Korean Art.

Li is a member of the East Asian Art Committee at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She serves on the boards of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra and the Pasadena Conservatory of Music.

Li was born and raised in Hong Kong and studied art history, East Asian studies and Chinese art history at the University of Toronto and University of Pennsylvania.

Young Yang Chung

Chung is a textile historian, museum founder and director, collector and artist. She is a scholar of East Asian textiles and author of numerous books on the subject. Passionate about the art of embroidery from an early age, she founded her own institute, the International Embroidery School, in 1965. She is a master embroiderer, with works in several museum collections. She received Master of Arts and doctorate degrees in art education from New York University in the 1970s, and in the following decades committed herself to studying and perfecting Asian embroidery techniques and transmitting her knowledge of textile skills and history to audiences worldwide. Through lectures, demonstrations, publications and teaching, she has endeavored to foster appreciation of an art form often stigmatized as “women’s work” and to challenge the notion of textiles as “minor arts.”

Chung founded the Chung Young Yang Embroidery Museum at Sookmyung Women’s University in Seoul, Korea, in 2004, which she continues to direct. She also founded the Seol Won Foundation with a mission to advance knowledge and appreciation of world textile arts and promote cultural understanding between peoples in the East and West, sponsoring a variety of art exhibitions and educational efforts such as lectures, workshops, research projects, study programs and scholarly exchange. Entering her second term with the museum, she has served with distinction as a trustee since 2018.

About the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art is committed to preserving, exhibiting, researching and interpreting art in ways that deepen our collective understanding of Asia and the world. Home to more than 45,000 objects, the museum stewards one of North America’s largest and most comprehensive collections of Asian art, with works dating from antiquity to the present from China, Japan, Korea, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Islamic world. Its rich holdings bring the arts of Asia into direct dialogue with an important collection of 19th- and early 20th-century American works, providing an essential platform for creative collaboration and cultural exchange between the United States, Asia and the Middle East.

Beginning with a 1906 gift that paved the way for the museum’s opening in 1923, the National Museum of Asian Art is a leading resource for visitors, students, and scholars in the United States and internationally. Its galleries, laboratories, archives, and library are located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and are part of the world’s largest museum complex, which typically reports more than 27 million visits each year. The museum is free and open to the public 364 days a year, making its exhibitions, programs, learning opportunities and digital initiatives accessible to global audiences.

National Museum of Asian Art Illustrates the Visual, Spiritual and Philosophical Power of Zen in Its Inaugural Exhibition for “The Arts of Devotion”

“Mind Over Matter: Zen in Medieval Japan” Launches “The Arts of Devotion,” a Five-Year Initiative Dedicated to Furthering Civic Discourse and the Understanding of Religion

For the first time since the museum’s founding nearly a century ago, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art will exhibit the breadth of its medieval Zen ink paintings, highlighting rare and striking works from Japan and China to unveil the world of medieval Japanese monasteries. Accompanied by ceramic and lacquer works, “Mind Over Matter: Zen in Medieval Japan” tells the story of the religious tradition’s birth in China around the fifth century and its expansion to Korea, Japan and eventually the United States. The exhibition will be on view in the museum’s Freer Gallery of Art from March 5 through July 24.

“Zen is a religion that is firmly rooted in the past, but deeply responsive to the present,” said Chase F. Robinson, the museum’s Dame Jillian Sackler Director. “How Zen monks expressed their religiosity and politics can teach us lessons about ourselves and our own time.”

As visitors journey through the exhibition, they will encounter monastic Zen paintings from medieval Japan (ca. 1200–1600), which are considered one of the great artistic traditions of East Asia and beyond. The abbreviated, seemingly impromptu paintings in monochrome ink have influenced artists and enthusiasts for centuries. Many of the most accomplished artists of this era—Mokuan, Ryozen, Shubun, Sesshu, Sesson and many others—were Zen monks credited by later generations as the creators of a unique and remarkable legacy of ink painting. Zen monk painters inspired a number of the most important professional painting lineages of Japan’s early modern period (ca. 1600–1868) and formed a thematic backbone of Japanese art and cultural identity in modern times. The exhibition is co-curated by Frank Feltens, the Japan Foundation Associate Curator of Japanese Art at the National Museum of Asian Art, and Yukio Lippit, the Jeffrey T. Chambers and Andrea Okamura Professor of History of Art and Architecture at Harvard University.

“Although Zen has come to embody notions of stillness and peace of mind, it is also a powerful philosophy embraced by monks over the centuries to challenge conventions of Buddhism and art,” Feltens said. “Ink is a basic yet incredibly versatile material in East Asian painting, enabling a wealth of individual expressions.”

As the inaugural exhibition of The Arts of Devotion initiative, “Mind Over Matter: Zen in Medieval Japan” seeks to enhance understanding of the religion and to foster empathy and respect among the public. In order to highlight key aspects of Zen as it is practiced today, the museum invited multiple perspectives: accompanying many of the works is commentary from high school students in Washington, D.C., award-winning koto musician Yumi Kurosawa and Zen priest Rev. Inryū Bobbi Poncé-Barger. Their observations reflect the ever-evolving nature of Zen and its teaching and its presence in the contemporary United States. A high school student from School Without Walls describes how the monochromatic ink paintings challenge expectations of Zen and Buddhism, while Poncé-Barger reflects on the expanded role of women in Zen practice in today’s society.

“Zen, like other religions, has never been a faith frozen in time,” said Hussein Rashid, the project director for The Arts of Devotion. “It evolves and acquires new meaning as new practitioners engage with the religion. ‘Mind Over Matter’ demonstrates the continuity of Zen tradition and the transformation of the religion over time and place.”

Additional highlights include a one-of-a-kind digital animation showing how an ink painting is made and “Voices of Zen: Contemporary Perspectives on Medieval Japanese Zen,” an online interactive feature that contains exclusive audio content from the community and curatorial voices. Contributors offer their individual perspectives on three important Japanese works from the exhibition. “Voices of Zen” will launch on the museum’s website prior to the exhibition’s opening.

“Guided by our commitment to experimentation, we sought to expand the reach of the exhibition to online audiences with a digital interactive and exciting animation,” Feltens said. “The cutting-edge animation and community voices create new avenues for engagement with and understanding of these artworks and Zen’s presence in our world.”

“Mind Over Matter” and The Arts of Devotion was made possible by Lilly Endowment Inc. Support for ”Mind Over Matter” and the museum’s Japanese art program is provided by Mitsubishi Corporation.

About the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art is committed to preserving, exhibiting and interpreting exemplary works of art. It houses exceptional collections of Asian art, with more than 45,000 objects dating from the Neolithic period to today. Renowned and iconic objects originate from China, Japan, Korea, South and Southeast Asia, the ancient Near East and the Islamic world. The museum’s Freer Gallery of Art also holds a significant group of American works of art largely dating to the late 19th century. It boasts the world’s largest collection of diverse works by James McNeill Whistler, including the famed Peacock Room. The National Museum of Asian Art is dedicated to increasing understanding of the arts of Asia through a broad portfolio of exhibitions, publications, conservation, research and education.

The National Museum of Asian Art was the Smithsonian’s first dedicated art museum and the first art museum on the National Mall. Since opening its doors as the Freer Gallery of Art in 1923, it has acquired an international reputation. The museum is preparing for its centennial in 2023—a milestone celebration and a springboard for the museum’s transformative vision for its next century, which will broaden and deepen the museum’s impact and reach, both onsite and online.

This Day in Freer History: November 22, 1920

The Museum Makes its First Purchase

On November 22, 1920, just over a year after Charles Lang Freer’s death, the Freer Gallery of Art initiated its first institutional purchases: two large stone wall reliefs that originated in the cave temples of Xiangtangshan, one depicting a gathering of buddhas and bodhisattvas and another depicting the Western Paradise of the Buddha Amitabha. Eventually a Song dynasty sculpture of a seated tiger also became part of the acquisition. Yet what seemed to be a straightforward and exciting purchase became an incredibly complex and lengthy process.

An Object of Interest

Lai-Yuan & Company, the New York gallery specializing in sales of Chinese antiquities, had the sculptures in its warehouse by October 1920. Having worked with Charles Lang Freer in the past, the gallery co-owners, C.T. Loo and F.S. Kwen, knew plans for the Freer Gallery of Art were developing rapidly.

They sent Katharine N. Rhoades, Freer’s former secretary and a newly appointed museum trustee, the description and cost of the sculptures on November 22. She shared the information with the museum’s director and curator John E. Lodge (served 1920-1942); Rhoades and Lodge quickly recognized these sculptures would be exciting additions to the collection.

Before his death, Freer mandated that purchases required the approval of his fellow collectors and friends Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer; Louisine Havemeyer; or Rhoades; and the Fine Arts Commission, led by the Secretary of the Smithsonian.

Knowing they needed more time to secure funds and meet Freer’s stipulations, Rhoades and Lodge requested that Lai-Yuan reserve the sculptures through January 10, 1921. Secretary of the Smithsonian Dr. Charles D. Walcott and Agnes Meyer traveled to New York in the new year and approved the sculptures. By January 10 the museum was poised to proceed with the purchase.

Problems Arise

Accountants finalizing Freer’s estate in Detroit, however, informed the Smithsonian that the residual funds that would pay for the sculptures could not be released until late April. Loo and Kwen expressed great frustration upon hearing this news, primarily because their business was closing. However, they agreed to accept payment in two installments when funds were released. With the closure of Lai-Yuan, Loo opened C.T. Loo Chinese Antiques and agreed to oversee the sale’s completion. When the sale encountered another delay after Freer’s estate realized funds would not transfer until May, Lodge asked Lai-Yuan to continue holding the sculptures. To sweeten the deal, he also asked to purchase a sculpture of a seated tiger that Walcott and Meyer had noticed at the gallery’s warehouse during their visit. The owners of Lai-Yuan accepted this plan, albeit noting bitterly in a letter to Lodge, “Were it not necessary for us to liquidate our stock at this time we hardly feel that we could have accepted [this proposal].”

The Sculptures Come to Washington

Thinking the deal complete, Lai-Yuan sent the sculptures via railway to Washington. Upon the acquisitions’ arrival in the capital city on March 26, the museum’s superintendent learned that one of the larger sculptures had broken during transport. Its crate was improperly braced and the train’s jostle had expanded old cleavages. Lacking supports, the sculpture’s midsection cracked into several pieces; rubble filled the bottom of the crate. The Lai-Yuan representatives were distressed, as their secretary had mistakenly secured travel insurance covering damage resulting only from “fire or collision.” Their negotiations with the insurance company remain unknown, but they reached a settlement in February 1922. On behalf of Lai-Yuan, Loo agreed to fund the repair. Museum staff followed the museum’s architect, Charles Platt’s suggestion that the sculptures be integrated into a gallery wall.

Repairs and Installation

Loo routinely wrote to Lodge, inquiring about installation, but it was not until a year after the accident, in March 1922, that the sculptures were finally installed. Loo sent Mr. Takenaka, a conservator from Japan to conduct “finishing touches” and when he completed work, Rhoades presented Takenaka with $15.00 for overnight accommodations and train fare, marking the completion of this 2-year endeavor.

Additional resource

Freer Gallery of Art, Postcards of “Scenes from Life of the Buddha” (F1921.1) & “The Paradise of the Buddha Amitabha,” 1929, The Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Department of Conservation and Scientific Research, Research Files.

Lunar New Year: Then and Now

For as long as I can remember, Lunar New Year has been the highlight of my year. Growing up in Taipei, Taiwan, I would receive red envelopes filled with money from my parents, grandparents, older relatives, and sometimes family friends. My grandmother was known for throwing very festive New Year gatherings with a spread of traditional Chinese dishes on the dinner table. I remember dining on a whole fish, Chinese New Year’s cake (niangao 年糕), and a traditional Chinese dessert of fermented rice with glutinous rice-flour balls (jiuniang tangyuan 酒酿汤圆).

For as long as I can remember, Lunar New Year has been the highlight of my year. Growing up in Taipei, Taiwan, I would receive red envelopes filled with money from my parents, grandparents, older relatives, and sometimes family friends. My grandmother was known for throwing very festive New Year gatherings with a spread of traditional Chinese dishes on the dinner table. I remember dining on a whole fish, Chinese New Year’s cake (niangao 年糕), and a traditional Chinese dessert of fermented rice with glutinous rice-flour balls (jiuniang tangyuan 酒酿汤圆).

Alongside the smell of incense burning in honor of our ancestors, our time together was filled with the sound of my grandparents and their friends speaking in their thick Shanghainese accents. When my grandparents left Shanghai and relocated to Taipei during the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949, they carried with them their dialect, their belongings, and their traditions.

Fast forward to the 1990s: my family and I emigrated to the United States, and I became preoccupied with assimilating into our new culture—and increasingly attached to pizza and MTV—while my ability to speak Mandarin slipped away one tone at a time. In those years, my mother sent us to weekend Chinese schools. And when Lunar New Year arrived, she would do her best to put together a hot pot (huoguo 火锅), a quick and convenient approach to a New Year dinner, to help hold on to our heritage.

Over the years, celebrating Lunar New Year has become less of a priority; keeping up with just one calendar and one New Year is hard enough! But as I embark on the journey of becoming a parent this year, I catch myself reminiscing about my childhood. Today, the idea of Lunar New Year is less about red envelopes and which Chinese dishes are on the dinner table, and more about the layers of cultural experiences and traditions that made me who I am. The beauty of a Ming ceremonial dish comes from not only its formal qualities but also the history it carries. So too does the beauty that surrounds the celebration of our cultural traditions.