The postscript is quite significant. Ana Mish Ma‘ahum enacts a long-running paternalistic discourse about the “problem of youth.” Should youth be secular national subjects or pious Islamic subjects? Should they work? Should they have fun? Most importantly, how should the older generation keep them from being drawn into political extremism? Ultimately the film shows youth staking out an independent position that is Islamic, but not Islamist. It turns out to be a problematic position, for reasons I’ll get to shortly. It is nonetheless an extremely interesting film. Bear in mind that until recently the Islamic trend, as it’s sometimes called, had no cultural program. Ana Mish Ma‘ahum connects with a new breed of Islamic preachers (or actually committed lay “missionaries,” known as al-du‘at al-gudaad) who regularly make pronouncements about the need for culture in a modern Islamic life. They include the well-known ‘Amr Khalid, who became prominent in the late 1990s, as well as even slicker du‘at, such as Mustafa Husni and Mu‘izz Mas‘ud.

The “new preachers,” as they are called, were initially stereotyped as “yuppies” who appeal primarily to the wealthy. This is a substantial oversimplification. However, it is true that ‘Amr Khalid and his clones can safely be thought of as products that have special appeal to the new suburbs. And in this connection, it must be said that the full impact of Ana Mish Ma‘ahum is not evident without a bit of further discussion of the ways that media define suburban space.

Ana Mish Ma‘ahum was set, and mostly filmed on location, in the newest suburbs of Cairo, far outside the urban location of modernity disseminated in countless mass-mediated narratives produced throughout most of the previous century. The locations chosen by the filmmakers are gated communities, which deliberately and firmly exclude the vast majority of the people who see Egyptian films.

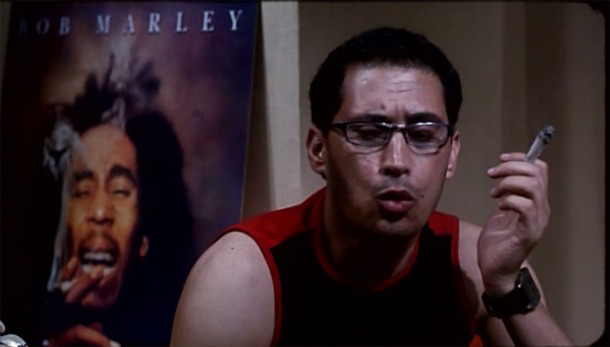

The film’s suburban setting in itself was not unusual. A fairly large proportion of contemporary Egyptian cinema visualizes the same locations, as do television narratives and other forms of visual culture—everything from billboards to home-furnishing magazines. But Ana Mish Ma‘ahum introduces a new dynamic to these conventions—namely the pointed insertion of Islamically marked bodies, both male and female, into the narrative and into the space of suburban Cairo. The normative exclusion of Islamically marked bodies runs through all mediated visual culture responding to the new exclusionary urban space that has expanded rapidly since the mid-1990s, and through the “old” visual culture that constructed urban (or more precisely, urbane) Cairo as the center of Egyptian modernity.

In mass-mediated visual culture produced before the mid-1990s, Islamically marked bodies were conspicuous by their absence in an urban landscape that had, over the 1970s and 1980s, been filled with such people. But the urban locations most familiar to this Islamically marked audience were still the indispensable canvas of the filmmakers’ labor. In more recent productions Islamically marked people are no longer conspicuous by their absence because the city itself also disappears, or more precisely, the densely urban city that the vast majority of Cairenes live in is replaced by locations in gated communities that only a few Cairenes live in and most will never see other than in mass-mediated representations.

The best way to illustrate this briefly is with a short video. This is not from a film, but rather a television advertisement for a new development called “Uptown Cairo.” It is the project of Egyptian billionaire Shafiq Gabr in partnership with the Dubai-based development company Emaar Investments. It will strike many as odd to contrast a film with an advertisement. The point is to emphasize the degree to which the production ownership of all mediated visual representations interpenetrates each other. The style of Ana Mish Ma‘ahum and many other recent films borrows heavily from the visual conventions of video clips. The entire genre of video clips is in essence an advertising platform for mobile phone companies, and many of the tycoons who have interests in mobile phones and other telecommunications and media-related businesses are the very same tycoons who are currently building housing developments like Uptown Cairo. The new suburban spaces of Cairo are inaccessible to the masses, but represented to the masses in media venues that are strictly controlled by the neoliberal tycoons. If Ana Mish Ma‘ahum is unusual in that it inserts Islamically marked people into this space, then it must be emphasized that there are no films that construct these vast new cities being built on the edge of Cairo as in any sense politically, economically, or environmentally problematic, even though vast sums of the state’s resources have been diverted to provide their infrastructure.