October 21, 2006–January 7, 2007

-

Dates

-

Location

Freer Gallery of Art

-

Collection Area

Ancient Near Eastern Art

“In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000” was a landmark exhibition presented in association with the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, which is the principal lending institution for this exhibition and is one of the greatest repositories for early manuscripts in the world. The Bodleian’s curatorial staff has also contributed to the shape of the exhibition and the exhibition catalog.

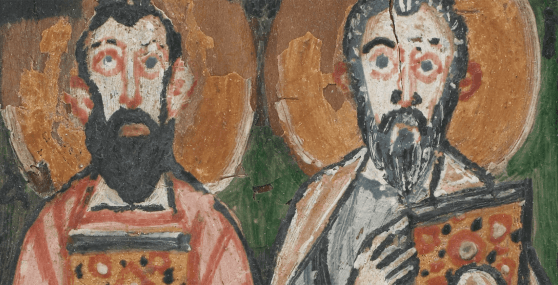

The exhibition coincided with the 100th Anniversary of Charles Lang Freer’s gift of Asian and American art to the people of the United States, now housed in the Freer Gallery of Art, and included several pages and fragments from Freer’s “Codex Washingtonensis,” fourth and fifth-century Old Testament Greek manuscripts. Also on view were a colorful painted cover of the “Washington Manuscript III—The Four Gospels,” depicting figures of St. Matthew and St. John

The exhibition presented over 70 of the earliest biblical artifacts in existence, including pages and fragments written in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Arabic, Syriac, Armenian, Ethiopian and Coptic—many on display for the first time in the United States.

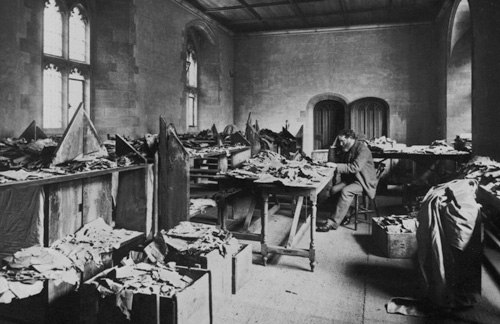

Solomon Schechter at work in the Cambridge University Library, 1898.

[The Cairo Genizah] is a battlefield of books, and the literary productions of many centuries had their share in the battle.... Some of the belligerents have perished outright, and are literally ground to dust in the terrible struggle for space, whilst others...are squeezed into big, unshapely lumps.

Solomon Schechter, The Times of London, August 3, 1897

The Christian concept of the Bible was established long before many of its earliest materials were discovered in the Middle East. It was only in the nineteenth century that European and American explorers, archaeologists, and others made their way to Egypt, seeking to learn how the Bible was transformed into a complex symbol of faith.

Exciting finds included the Cairo Genizah, associated with the thousand-year-old Ben Ezra Synagogue. A genizah was a sealed room where copies of scripture with scribal errors were stored until they could be ritually destroyed. In 1896–98, Cambridge University academics Solomon Schechter and Charles Taylor shipped the bulk of the Cairo Genizah's contents to Cambridge for further research. Photographs taken at the time convey the excitement of the scholars who were the first to study these long-lost works.

Image 1 of 9

Left to right: Dr. Frederick W. Mann, Charles L. Freer, Ibrahim Ali, and Ali Arabi, in Cairo, January 1907. Freer Gallery of Art.

Image 2 of 9

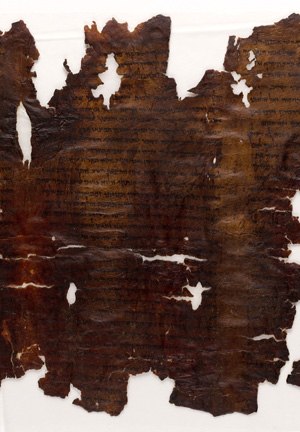

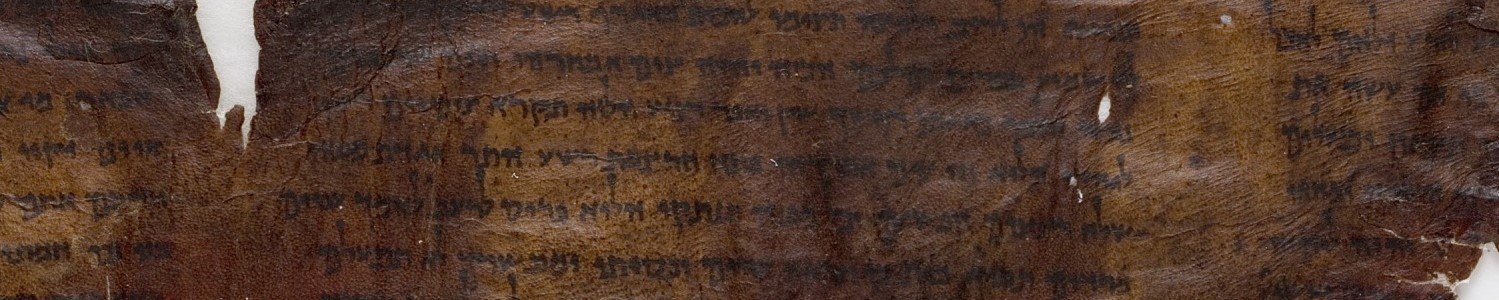

The Dead Sea Scrolls: Isaiah Scroll, Manuscript B

Jerusalem, The Shrine of the Book, 95.57/26B

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (owner)

MS. B (1QIsab [1Q8])

Ink on leather; 1 leaf (part of a scroll); 220 x 430mm

Bible (fragment); Hebrew

Judaean Desert, Israel; before 73 C.E.

Image 3 of 9

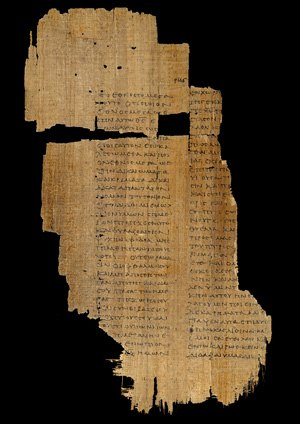

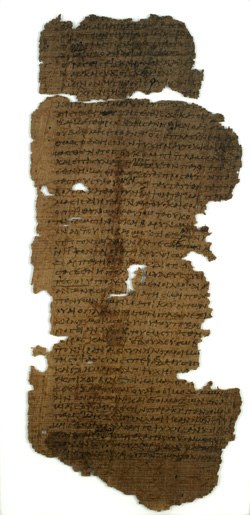

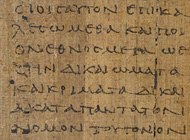

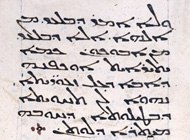

The Chester Beatty Numbers and Deuteronomy Codex

Dublin, Chester Beatty Library

MS. Biblical Papyri VI (Rahlfs 963), ff. 63v, 64v

Papyrus; ff. 50; 280 x 180mm (original size 330 x 190mm)

Numbers and Deuteronomy; Greek

Fayyum or Aphroditopolis (modern Atfih)

Egypt; ca. 150 C.E.

Image 4 of 9

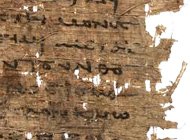

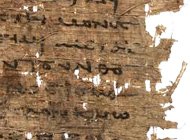

The Sayings of Jesus (Logia Jesou)

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Gr. th. e. 7 (P), recto and verso

Ink on papyrus; f. 1; 140-48 x 90-95mm

Gospel of Thomas (fragment); Greek

Oxyrhynchus, Egypt; third century C.E.

Image 5 of 9

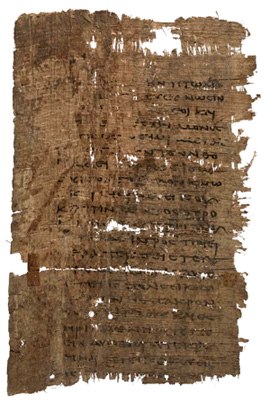

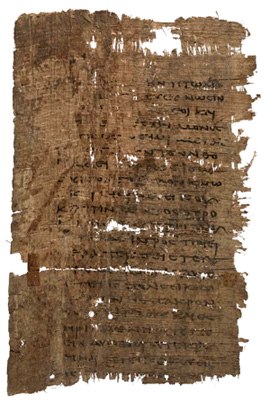

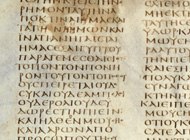

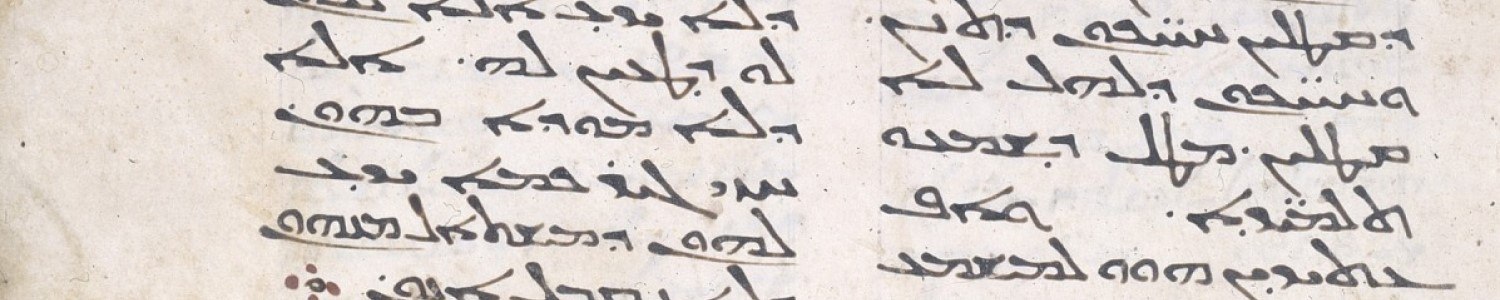

The Washington Codex of the Minor Prophets

Washington, D.C., Freer Gallery of Art, F1916.768 (MS V), p. 37

Ink on papyrus; ff. 34 + fragments; 295 x 140mm

Minor Prophets; Greek with Coptic glosses

Egypt, Fayyum(?); third century, second half

Image 6 of 9

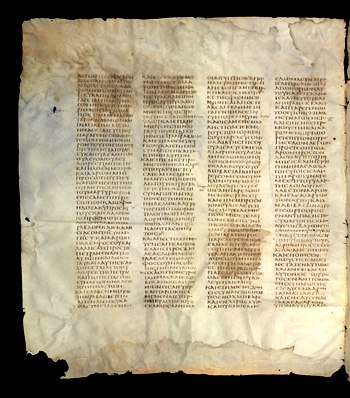

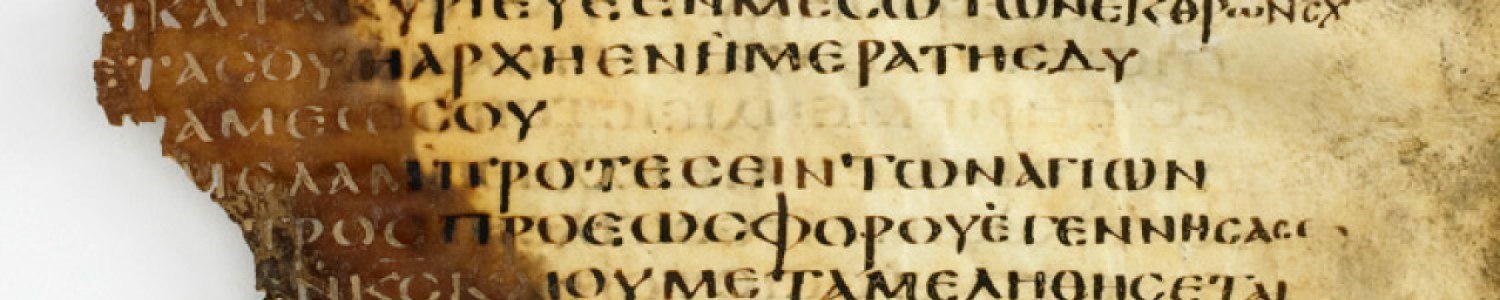

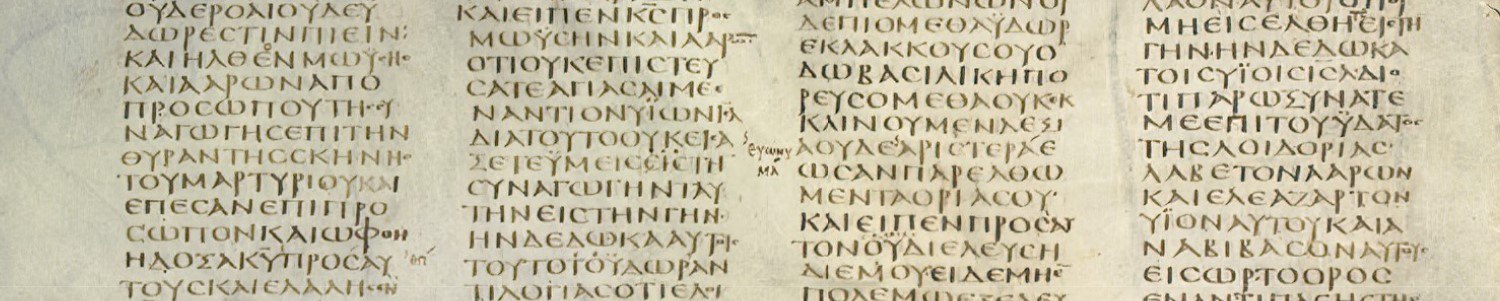

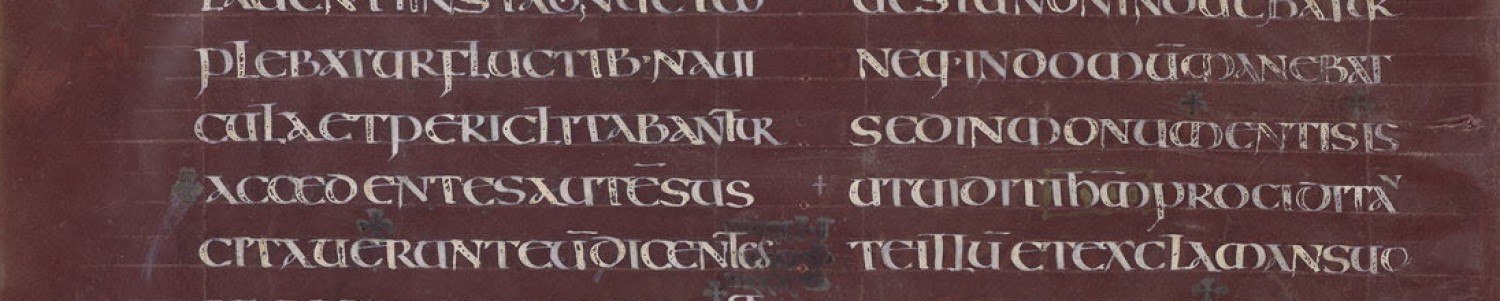

Codex Sinaiticus

The Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine, Mount Sinai

Codex Sinaiticus; unnumbered bifolium

Ink on parchment; ff. 730 (originally); 363 x 332mm

Passages from the Book of Numbers; Greek

Uncertain provenance (Rome? Caesarea? Alexandria?); fourth century

Image 7 of 9

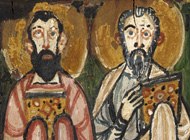

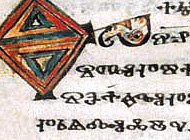

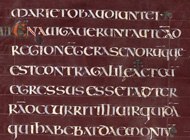

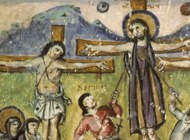

Painted covers from the Freer Gospels

Washington, D.C., Freer Gallery of Art, F1906.297 (Matthew and John), F1906.298 (Mark and Luke) (MS. III; Codex Washingtonensis)

Covers from the Freer Gospels; Greek

Encaustic (wax) painting on wooden boards; 213 x 143 x 16mm (each board)

Coptic Egypt; seventh century

Image 8 of 9

The Sayings of Jesus (Logia Jesou)

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Gr. th. e. 7 (P), recto and verso

Ink on papyrus; f. 1; 140-48 x 90-95mm

Gospel of Thomas (fragment); Greek

Oxyrhynchus, Egypt; third century C.E.

Image 9 of 9

Discovering the Bible

The Bible has been called the best-selling book of all time, though the term itself comes from biblia, Greek for a collection of books. The Bible developed gradually, over many centuries, as the result of cultural interaction and exchange among many different societies. Over time, some texts were accepted as part of the canon of belief, while others were excluded as apocryphal and heretical. Out of this rich diversity and cultural complexity emerged the modern Bible.In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000 tells the story of this formative period. The exhibition brings together a rare assemblage of several important early Hebrew and Christian bibles—the first time many of these fragile treasures have been shown to the public. This exploration of the Bible’s first thousand years also reveals the parallel development of the book—one of the world’s great technological revolutions.

From fragile fragments of papyrus and humble early parchment codices to resplendent illuminated manuscripts, In the Beginning presents the physical evidence of the earliest versions of both Bible and book. Some of these manuscripts have remained in ancient monastic libraries or cathedral treasuries since they were written. Others have languished, concealed in desert caves, sealed up in long-forgotten rooms, or buried to await resurrection by archaeologists. Each has its own distinctive a tale to tell.

The quest to discover ancient biblical manuscripts

The Christian concept of the Bible was established long before many of its earliest materials were discovered in the Middle East. It was only in the nineteenth century that European and American explorers, archaeologists, and others made their way to Egypt, seeking to learn how the Bible was transformed into a complex symbol of faith.

Exciting finds included the Cairo Genizah, associated with the thousand-year-old Ben Ezra Synagogue. A genizah was a sealed room where copies of scripture with scribal errors were stored until they could be ritually destroyed. In 1896–98, Cambridge University academics Solomon Schechter and Charles Taylor shipped the bulk of the Cairo Genizah’s contents to Cambridge for further research; some of those fragments are exhibited in this gallery. Photographs taken at the time convey the excitement of the scholars who were the first to study these long-lost works.

The role of American collectors

A number of collectors felt the thrill of the chase for biblical manuscripts, and they relished the clandestine negotiations surrounding their purchases. “I am a little in doubt as to the wisdom of letting it be known…that I anticipate visiting Egypt,” explained Detroit industrialist Charles Lang Freer, “as one can never measure the competition that may spring up if it is known a real search is being made for rareties.”

Freer’s 1906 purchase of early biblical manuscripts from Ali Arabi, a dealer in Giza, Egypt, includes two substantially complete Greek codices dating from the late fourth or early fifth century. One contains the books of Deuteronomy and Joshua and the other the Freer Gospels, also known as Codex Washingtonensis—one of the earliest versions of the Greek Bible. Freer also acquired codices of the Psalms, the Epistles of Paul, and, in 1916, the Minor Prophets. He even bought an early Coptic bookstand on which such volumes would originally have been displayed. Freer’s collection of manuscripts remains the most important of its kind outside the Middle East and Europe.

The American mining engineer Alfred Chester Beatty was a prominent collector of early biblical materials, many of which he purchased from Egyptian dealers. Consequently, the find sites of these items are unknown, though most are thought to have come from the Fayyum (an area southwest of Cairo). Beatty’s collection, now housed in Dublin Castle, includes twelve important early Christian codices dating from the third to fourth century: their discovery was announced in The Times of London on November 17, 1931.

Discovering the Bible: Part I

You are listening to Michelle P. Brown, curator of the “In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000” and professor of medieval manuscript studies at the University of London.

For me books are portals into past lives. And books of all things give you that in to the way people thought about things, sometimes even the way in which they felt about things, how they made things, the relationships of who actually starts the ball rolling on a commission, who are the people who actually pick up the quill pen and write or who pick up the brush and paint. And who are the people who are then actually receiving their work and how might it have impacted on their lives. So for me the book opens up the whole vast range of human activity and achievement.

The Bible, of course, is the best selling book of all time. And I think to actually have the excitement as a curator of bringing together materials from all around the world that actually show how something that to us now seems straightforward and iconic—”The Bible”—as if it’s always been there, just as one thing, to actually see that is the result of many, many different societies that have worked together, collaborated together, sometimes even conflicted with one another over the ages, and that gradually it’s our perception that changes and that helps to bring the idea of an iconic thing, like the Bible, into creation.

So really a show like this just allows you to mount the most incredible archeological dig of your own, to actually get down to those levels of, how did this come about, and what does it tell us, not only about the past, but also about how we see ourselves and how we ask questions about our memory and identity now.

Discovering the Bible: Part II

You are listening to Michelle P. Brown, curator of the “In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000” and professor of medieval manuscript studies at the University of London.

The 19th century was an age of great intellectual ferment and new possibilities and new ways of thinking. And, for example, Darwin’s publication of “The Origin of Species” caused an awful lot of people to become very afraid that it was challenging the basis of their belief and how they perceived things to tick and how creation had come into being, etc. And so you find that increasingly there is an attempt to verify the narrative of the Bible.

And many expeditions were dispatched from, for example, London and Berlin, off to the Middle East in order to dig up the proof of the bible. There were also many collectors who enjoyed the thrill of the chase. And we owe some of the most important finds and collections of early biblical material to some of those almost Indiana Jones type quests to find these early materials.

And so we find people like the American mining engineer, Alfred Chester Beatty, using his small self-made fortune in order to buy up some of the earliest papyrus fragments and fragments of codices that are now housed in Dublin castle as part of his collection in the Chester Beatty Library. We find others, such as the Detroit industrialist, Charles Lang Freer, going out to Egypt himself. And he had a particularly good time in 1906 with an antiquities dealer in Giza round by the pyramids on the outskirts of Cairo. And he managed to make a number of purchases that, I mean his collection is the most important of its type outside of the Middle East and Europe. And he not only purchased one of the earliest and most important witnesses to the gospels, the Freer gospels, which dates to the late 4th, early 5th century, and which has the most beautiful covers from 7th century Egypt still surviving, with images of the 4 evangelists painted in wax, in caustic wax, glowing luminous colours; an incredible fragile and remarkable survival. He even bought the Coptic book stand that these books would have been read from in the early churches of the period, as well.

Discovering the Bible: Part III

You are listening to Michelle P. Brown, curator of the “In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000” and professor of medieval manuscript studies at the University of London.

Another remarkable find was the Cairo Geniza. A Geniza is a room in which flawed, imperfect or used copies of Hebrew scripture are stored before they can be ritually disposed of. You couldn’t just throw away a damaged or badly worn copy of Hebrew scripture because it was sacred. The one in the outskirts of Cairo was founded in 882 and its doors were not opened until the 19th century when the dealers finally got in. And imagine the wealth of material that that brought out. And so we can share the excitement of these people as they traveled to these exotic parts and were suddenly face-to-face with materials nearly 1000 years old. That excitement is still palpable as you look at those tiny little fragments today.

And the thing that we have to bear in mind is that, you know, the centuries and centuries of scholarship that has gone into biblical studies, much of it was conducted without recourse to any of this evidence. Because things are still being discovered today. But things like the Dead Sea Scrolls, for example, which may have been concealed in a little cave in the Judean desert at Qumran around the time that Masada was being defended, the last heroic stand of Israel against the Roman destruction in 73 AD, we find that that material wasn’t known until the 1940s. Likewise, the Nag Hammadi Codices, which were found by a Bedouin peasant again in Egypt. And none of these things were available for those people to study. The Codex Sinaiticus wasn’t known until Tischendorf pulled part of it out of St. Catherine’s Sinai in the mid-19th century.

And so in a way, people are having to revise their views all the time. And again, that can still make people uneasy. Are they going to find something that’s going to challenge my belief and make me think about it in a different way? Well, they might. However, the Dead Sea Scrolls are showing that a lot of material is actually corroborating in different ways as well. But you have to be prepared to carry on being open to be pleasantly surprised and challenged by the material, because it undoubtedly has new things to tell us and always will.

The Earliest Scriptures

From Scroll to Codex: The earliest Hebrew scriptures

Until the fourth century, the standard form of a book for people was not a book at all. Rather, it was a roll—also called a scroll or bookroll—made of papyrus or animal skin on which a text was inscribed by hand. The earliest books of the Hebrew Bible survive today in scroll form. Known as the Dead Sea Scrolls, they were discovered in the Judaean Desert in the 1940s and include the Second Isaiah Scroll.

The Hebrew Bible—the thirty-nine books of the Torah, Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings)—was formed over a number of centuries. Between 500 and 900 C.E. scribes called the Masoretes established the pronunciation of words and the division of paragraphs and verses.

But the Hebrew Bible was not the only version in circulation. Many Jews and early Christians used a Greek translation, probably begun during the third century B.C.E. It was called the Septuaginta (Latin for “seventy”) because according to legend, it was produced by seventy-two Jewish scholars. It included fifteen texts omitted from the Hebrew Bible and was the basis for many of the manuscripts in this exhibition.

In the first century, a new kind of publication appeared: the codex or leaf-book, a series of pages bound together at one edge and protected by covers. Its increasing popularity was directly connected to the formation of the Christian Bible. Codices made cross-referencing between biblical books much easier and were more readily portable than scrolls. These benefits appealed to Christian audiences, particularly during times of persecution.

Because Christianity emerged as a sectarian type of Judaism rather than an independent religion, the Bible of the earliest Christians was the Bible of Judaism. Two codices on display in this exhibition, the Aleppo Codex and the St. Petersburg Pentateuch, formed the basis for what became the standard text of the Hebrew Bible.

As Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire, the codex gradually displaced the scroll as the medium for non-Christian texts as well. By the time Christianity was established as the empire’s official religion in the fourth century, the codex had become standard. This was a monumental change in the history of the book, comparable to the invention of movable type in the fifteenth century or the electronic text of the modern era.

The Earliest Christian Scriptures

Composed in Greek, early Christian texts were not intended as “biblical” books as such but were written in response to the needs of local Christian communities. Ultimately many of these writings came to form the New Testament, including the canonical gospels attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. But that was the result of a long process not imagined by their authors.

Perhaps because they relied on the scriptures of Judaism, early Christians were slow to produce writings of their own. The earliest to survive are the letters of Saint Paul (50–60 C.E.) and the Gospel according to Mark (65–70 C.E.). These were followed around 80–90 C.E. by the longer Gospels of Matthew and Luke (the latter accompanied by the Acts of the Apostles), along with a lost source that scholars call “Q,” which contained sayings and parables of Jesus and some episodes from his life. Saint John’s Gospel appeared around 85–95 C.E., as did the letters of James, Peter, and John; Paul’s letter to the Hebrews; and the Revelation of Saint John (the Apocalypse).

Christian writings then proliferated, with more letters and revelations/apocalypses as well as a variety of gospels eventually omitted from the Christian Bible. These include the Unknown or Egerton Gospel and the Gospel of Thomas, both on display in this exhibition. Other writings have been attributed to Christians and Gnostics, a sect that sought mystical enlightenment as a means to salvation.

The Earliest Scriptures: Part I

You are listening to Michelle P. Brown, curator of the “In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000” and professor of medieval manuscript studies at the University of London.

When early Christian communities started to form in the 50, 60 years or so after Christ’s crucifixion, they didn’t actually feel the need to create a bible of their own. They had scripture already. They had Hebrew scripture, what we think of as the Old Testament. But what they did need were examples, instructions, things that actually told them how they might live the Gospel message. How would they function as communities, what impact were they going to make on the lives of others and on their world to the good.

And so you find that the earliest things to be written were epistles, were letters, as you would, you’d send a letter to a new community encouraging them, giving them a few ground rules perhaps, picking out a few individuals who might be able to help lead that community, etc. And so that’s exactly what we find. The earliest Christian writings to be produced are letters from figures like St. Paul actually encouraging new churches in just living a basic life. And some of the earliest materials that we find from the desert sands of Egypt, Palestine are simple little pamphlets, just the sort of thing that you might stick in your pocket or your satchel and carry around with you if you needed to whip them out to actually speak to a group of people that you were going to spend the night with, to have dinner with, to share Agape, the love feast recalling the Last Supper, and to actually share that inspiration with them.

The Earliest Scriptures: Part II

You are listening to Michelle P. Brown, curator of the “In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000” and professor of medieval manuscript studies at the University of London.

Then about the year 70 to 80 in the first century after the birth of Christ, gospels are written. Now that’s an English word. It comes from the old English “godspel,” good news. You want to share the good news. But basically gospels were simply accounts mostly from oral tradition, the things people had heard and that they passed on to each other over the dinner table, on the street corners, walking together on journeys, about things that Christ had been reported to have said and to have done. Many, many different writings in circulation, and all of them with a purpose, a practical purpose for people wondering about once they’d received that good news what were they to do with it. How could they share it in the best possible way with others and how could they actually transform society.

Because of course it was radical. It could lead seasoned warriors to embrace pacifism and walk out onto the field only with a wooden stick against those coming down with them with great sharp weaponry. And it could lead kings to free slaves, potentially overthrowing the whole of the society that they were supposed to be maintaining. And so these early witnesses are very, very dynamic, simple, humble writings, but with a very, very immediate and practical purpose.

When we see some of the earliest papyrus scrolls and fragments of books that have come from Judea and from the deserts of Egypt, we have to think about the communities that used them and the way in which their need for gospels, for epistles, for practical working manuals of faith and the way in which they spoke about them to others, they way in which they spread the Greek message of the gospels in the Syriac, Aramaic tongues and others, we’ve got to think about them actually forming the Bible.

Really the big test is did people keep on using them, reading them, did they find these things sustaining for the way in which they lived their lives. And that I think more than almost anything is the bedrock of how the bible evolves; how it takes shape. It’s the fact that people spoke about it and lived it. And so that’s what we need to think of alongside all of that marvelous Biblical scholarship from the 4th century right up to the present. They work together to give us the sense of what the Bible is.

Formation & Codification

In 303 C.E., during the “Great Persecution” of Christians, the Roman emperor Diocletian ordered the destruction of Christian books. But only ten years later—following his vision of the Cross and subsequent victory in battle—Emperor Constantine granted religious toleration throughout the Western Empire. This toleration was extended in 324, when he united the empire’s two halves, establishing a new “Rome” at Constantinople.

Constantine (died 337) and his successors convened councils to determine the nature of Christian belief; many churches were founded, all requiring collections of Christian texts. In 332 C.E., for example, Constantine commissioned fifty copies of Christian scriptures for his foundations from the biblical scholar Eusebius of Caesarea (circa 260—339). Christian writings began to be gathered together in large, expensive books, appropriate for use in prestigious surroundings.

Later in the fourth century, the Roman Empire adopted Christianity as the state religion. This gave further impetus to the production of the biblical “canon,” that is, a fixed list of books understood to have unique status by virtue of divine inspiration. Before this time, a great number of texts had been in circulation, bearing out the words of Saint Luke that “many” were writing about Jesus. Some texts came to be rejected due to dubious authenticity or association with radical sects. More of these have come to light in modern times, including, most recently, the Gospel of Judas.

From Greek to Latin

The earliest complete Christian bibles—Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Vaticanus, and Codex Alexandrinus—were written in Greek and date from the fourth to fifth centuries. They were powerful symbols for Christians, physically expressing the unity of the Old and New Testaments, but they were rare even in their own time, being impractical to use and expensive to produce.

Codex Sinaiticus is thought by some scholars to have been made in Caesarea (in modern Israel) as early as the fourth century. This area hosted much of the research and writing conducted by two influential Early Christian scholars: Saint Jerome (circa 347–419/20) and Bishop Eusebius (circa 260–339), who devised a system of canon tables that allowed comparisons across the gospels. Although Codex Sinaiticus cannot be directly connected to either man, it certainly flourished in the same fertile intellectual soil.

Christian scriptures usually circulated in the form of smaller collections of gospels or epistles. Early gospelbooks include the Harley Gospels, an example of Jerome’s “Vulgate” edition of the Bible—so named because it was in the common (vulgar) language of the day, Latin, the basis of the emerging “Romance” languages.

Formation & Codification: Part I

You are listening to Michelle P. Brown, curator of the “In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000” and professor of medieval manuscript studies at the University of London.

Once Christianity had come out of the closet and was the state religion of Rome, you find that you start having lots of church councils convened. Because many local churches have grown up all the way around the Mediterranean. And they’ve got to find a common way of doing things and they don’t always actually agree on those things. And so you find a whole process of “what’s in, what’s out; what’s heretical, what’s orthodox.” And that applies to the texts as well.

And we know that at the time, that a list that’s in one of our prime exhibits, the Codex Caramontanis, which is a little bit later, but the list itself was probably written in the 4th century, that there’s still a great deal of controversy about what is canonical, what is divinely inspired and which can all of those churches subscribe to collectively, and which are apocryphal, which ones are out. And we find that in Codex Caramoutanis there’s a list by Athenaeias of Alexandria we think that actually refers to a whole range of books that were accepted as canonical. There are other lists that survive that differ. Some say 21 books were acceptable; others say 27. One that’s particularly contentious, for example, is the Book of Revelations, or Apocalypse. Some say it’s in, some say it’s out, some sit on the fence. Other texts, which at that time were considered perfectly acceptable and should be in, such as the Sheppard of Hermes, were later thought not to be reliable and were taken out of the equation.

And so it’s very, very fluid. As people try to get back to the idea of, where has this come from, who’s worked on it, what is the authenticity, what is the authentic voice that we’ve got here.” And if you can imagine that was a very long and painstaking process and not everybody agreed. Scholars today still don’t necessarily agree on it.

Spreading the Word

The Bible and the codex initially took shape within a Roman Empire that stretched from Syria to Scotland. Greek and Latin were the literary languages, and by fourth century Christianity was the state religion. In the early Middle Ages individual nations began to emerge, with their own languages, cultures, and religious traditions—orthodox Christian, heretical, and pagan—all influencing the ways in which Bible and book were perceived and produced. Still, the concept of “empire” continued to haunt ambitious leaders who saw faith as a way to unite their diverse subjects.

Disseminating a religion of the Word involved both finding interpreters to preach in local languages and teaching people sufficient literacy for reading and copying texts. Missionaries often used a written version of the spoken language while different sounds required the creation of suitable scripts. That was the case with ninth-century missionaries Saint Mesrob, who created the Armenian and the Georgian alphabets, and Saint Cyril, who developed what would become the Cyrillic alphabet.For those who dedicated their lives to God’s service, to be entrusted with the transmission of his Word was a high calling indeed. Books became channels of the Spirit, and gateways to revelation: for In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God (John 1:1).

From Babel to Pentecost

Christ’s teachings first circulated orally in a local language called Aramaic, and throughout the Middle Ages, most people’s knowledge of scripture continued to be oral and visual. They heard it through the public recitation of snippets of scripture and in sermons, poems, storytelling, and song. And they saw it in the images beautifying church buildings, carved on wayside crosses, or adorning the possessions of the wealthy. Psalters (books of psalms) and prayerbooks were used for public and private worship, while gospelbooks graced the shrines of saints and were used during services or displayed on the altar, where they also served to solemnify legal transactions and oaths.

The transmission of scripture also promoted the use of written vernacular (local) languages. This development took on a different character in the East and West, shaped by varying cultural attitudes. Around the Mediterranean, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin were traditionally the “sacred languages” used for scripture. In western Europe, Latin—the common language of the Roman Empire—assumed this role. And while tension between “official” written languages and those spoken locally later became an issue in the West, there was no such tension in the Churches of the Christian Orient (Syriac, Coptic, Ethiopic, Armenian, Georgian). Indeed, the popularity of religious texts in local languages owed much to the desire of those regional Churches to preserve their own identities.

The book as desert, the scribe as evangelist

There were no rules governing how books of scripture were made in the Middle Ages. For some scribes it was part of the daily round of monastic life, conducted in collaboration with colleagues. Others preferred the more solitary model of early saints such as Paul and Anthony of Egypt, who sought spiritual challenge in the desert. Emulating those desert hermits, some scribes living in the watery wildernesses of northern Europe worked alone within the scribal desert of the book—a place of meditation, prayer, and encounter with the Divine.

The Italian monastic founder Cassiodorus (circa 485–580) lauded such scribal endeavor, writing that the scribe preaches with the pen and unleashes tongues with the fingers, and that each word written is a wound on Satan’s body. In monasteries on the Atlantic seaboard, Saint Columba and other scribes were acclaimed as heroes.

Byzantine depictions of the evangelists helped to promote this concept by setting the scribe’s labors against a timeless spiritual background of gold. Evangelist portraits also affirmed that the image of the book symbolized the scriptures of Christianity, just as the scroll did those of Judaism.

Women, too, served as scribal evangelists. Female scribes are known to have supplied books for churches and missions in England, France, and Germany.

From Eastern deserts to Western isles

During the early Middle Ages, monasteries in two far-flung regions—the desert sands of Egypt and the seascapes of Britain and Ireland—shared perceptions about the role of the book. The allure of the Holy Land, often visited by Westerners on pilgrimage, and a sense of their own remoteness from the Mediterranean world may have contributed to the fertile reception of eastern influence in Britain and Ireland.

Around 400 C.E., for example, a Coptic psalter was placed in the grave of an adolescent girl, reflecting the ancient practice of interring the Book of the Dead with the deceased. Likewise, in northeast England in 698 the relics of Saint Cuthbert were buried with a copy of Saint John’s Gospel, bound using a complex Coptic sewing technique and a tooled leather cover. Book-shrines also were made in both regions, with their contents revered as relics themselves. The colorful griffins in the margins of the Lectionary of Mount Horeb have parallels in the lion symbols of Saint Mark in early Irish gospelbooks, such as the Macregol Gospels.

The traditions of East and West came together at the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai. Founded between 548 and 565, it was home to Greek, Syrian, Arab, Georgian, Slavic, and Latin-speaking monks, who copied scriptural and liturgical books into their various languages.

The monastery also holds a few Latin manuscripts made before 1000, evidence that Latin speakers were in the region long before the Crusades. In 599, Pope Gregory the Great sent an envoy bearing gifts to Sinai, so there were evidently early communications between East and West.

Early Christian Britain and Ireland

As the Roman Empire contracted during the early fifth century, England was increasingly settled by pagan immigrants from Germany and southern Scandinavia—the Anglo-Saxons. Their conversion to Christianity gained impetus with a mission sent by Pope Gregory the Great and led by Saint Augustine, who arrived in Kent in 597.

The English, as the Anglo-Saxons became known, also had contact with missionaries from Ireland, which was introduced to Christianity in the fifth century. Irish monasteries produced books exuberantly written and decorated in Celtic fashion, such as the Macregol Gospels. Along with their English counterparts, they blended elements from Celtic, Germanic, Mediterranean, and Middle Eastern traditions to form a distinctive cultural style known as “Insular” (circa 550–850). English scribes produced striking copies of scripture such as the Cambridge-London Gospels, devised their own system of scripts and style of illumination, and followed the Irish example by introducing word-separation and systematic punctuation to clarify legibility.

The English and Irish also used their own languages to share the “good news” (in Old English, godspell). The scholar Bede, a monk in northeast England, admired the way Jews shared their scriptures with gentiles and encouraged the use of the English language to bring Christianity to others: on his deathbed in 735 he was translating Saint John’s Gospel.

In the mid-tenth century, people started to translate gospelbooks into English through glosses written between the lines of the Latin texts. By the year 1000 parts of the Bible were being paraphrased in local languages with extensive illustrations, as in the Junius Manuscript—word and image working in harmony to expound the meaning of scripture.

Spreading the Word: Part I

You are listening to Michelle P. Brown, curator of the “In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000” and professor of medieval manuscript studies at the University of London.

Throughout the Middle Ages most people would actually hear things rather than read them. They would hear songs, they would see plays even if it was only in the street or the tavern. They would see images. So, not everybody who saw a book would actually be able to read it.

However, if you’re looking at an incredibly beautiful illuminated gospel book, for example, the Lindesfon Gospels, the Book of Kells, the Rabbula Gospels, which is in the show from Syria, 6th century, and you saw something like that on the high altar at a church perhaps where there was a major cult where a saint was buried and you would go on pilgrimage for a miracle of healing. And if you’ve dragged your granny three hundred miles to be healed you expect it to change all of your lives.

Now, if, around 800, you were to come to a shrine of St. Colombo, or somebody of that sort, and you saw a book like this, you would see some things that would immediately made you feel at home. For example, you might see the swirling spiral work that was the sort of thing that was on your great-grandmother’s brooch. And you knew that she had come from the southern parts of Ireland and that this was something that spoke of her culture. You might find that there were animal ornament, interlaced birds, beasts, hounds, all forming the words and the letters themselves, the whole of creation supported by “the Word.” And you’d recognize that as a sort of decoration that your grandfather had on his belt buckle when he was an auxillary in the Roman army.

And so even if you weren’t able to read the impact of the image, of coming from a wild environment into a church that suddenly was ablaze with candles, which had images all over the walls, heavily embroidered curtains, glittering chalices, and most importantly, a gospel book of this sort on its high altar, would totally blow your mind.

Book as Icon

While the earliest written Christian scriptures were simple, unadorned manuals, by the fifth and sixth centuries opulent materials, such as purple-stained pages and gold and silver inks, were used to confer prestige, and didactic picture cycles appeared on the walls of churches and in books.

Unease concerning idolatry in Jewish, Islamic, and Christian circles led to the destruction of images in the movement known as iconoclasm, which beset the Eastern Church in Byzantium during the eighth and early ninth centuries. Western Church authorities, however, understood that illustrations could convey the meaning of scripture; around 600, Pope Gregory the Great advised that in images the illiterate read.

Meanwhile, due in part to enduring Christian tradition, people continued to use distinctive and lavish forms of decoration to celebrate the Word of God. The sacred book became an iconic object, carried ceremonially in procession, read from during the liturgy, and displayed on the high altar.

By the year 1000, illuminated books symbolized the ongoing transmission of the Word. Books helped people believe that the Christian Bible had been handed down as a powerful unified whole. The transition from late Antiquity to the Middle Ages, and with it the process of formation of the Christian Bible, was complete.

Book as Icon: Part I

You are listening to Michelle P. Brown, curator of the “In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000” and professor of medieval manuscript studies at the University of London.

In a way the picture that emerges in the early middle ages is that the Bible is The Book. It comes to assume an iconic significance. It looks incredible. It might have a treasure binding with jewels and gold on the outside and it might have resplendent images and beautifully written words when you open it up.

One of our exhibits is a little commentary on the Apocalypse, which belonged to a missionary called St. Boniface, who was born in the south-west of England, at Crediton, and who in the early 8th century set out to become the apostle to the Germans. And he writes back letters to one of his greatest friends at home, Abbess Eadburh, who ran a nunnery at Minster-in-Thanet in Kent near the place where Augustine had first set foot to try and convert the pagan Germanic settlers after the Romans had pulled out. And he writes back, “Please can you send me more books, Eadburh? Can you send ones that are in larger, more formal writing because my eyesight’s going a bit now and I can’t read the joined up writing in the way in which I used to. And please can you send me copies of Scripture that are illuminated with gold, that I’m sending you for the purpose, because we need to wow the natives. We need to impress them.”

Another way in which books of these sorts were sometimes used was that they would be available on the high altar for swearing the most solemn of oaths, transacting the most formal of legal transactions, if you were making a big alliance or treaty, if you were conveying some property changing hands, you would actually go to the shrine with a book of this sort and you would swear your oath upon the Bible, in the same way as we often still do today as part of our legal process, as swearing upon something that’s sacred to you.

Resources

Dr. Zaza Alexidze (ZA)

Professor and Head of the Scientific Department of the K. Kekelidze Institute of Manuscripts in Tbilisi

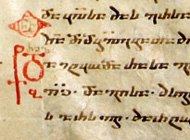

Georgian Gospelbook

Dr. Bruce C. Barker-Benfield (BCBB)

Senior Assistant Librarian, Department of Special Collections and Western Manuscripts, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

The Sayings of Jesus (Logia Jesou)

Monica J. Blanchard, Ph.D. (MJB)

Curator, Semitics/Institute of Christian Oriental Research Collections, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.

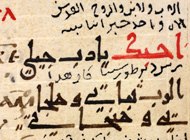

Greek–Arabic Diglot of the Psalms and Odes

Michelle P. Brown (MPB)

Professor of Medieval Manuscript Studies, University of London; Visiting Professor, Leeds University; Regional Programmes (and formerly Curator of Illuminated Manuscripts), British Library; Lay Canon and chapter member of Saint Paul’s Cathedral, London

Right cover of the Washington Manuscript

Codex Zographensis

Ethiopic Gospelbook

The Stockholm Codex Aureus

Dr. Malcolm Choat (MC)

Associate Lecturer, Department of Ancient History, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

The Washington Codex of the Minor Prophets

Harry Y. Gamble (HYG)

Professor and Chair, Department of Religious Studies, University of Virginia, Charlottesville

Codex Sinaiticus

Ann C. Gunter, Ph.D. (AG)

Head of Scholarly Publications and Curator of Ancient Near Eastern Art, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Saint Ephrem’s commentary on Tatian’s Diatessaron

Charles Horton (CH)

Curator of the Western Collections of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin

The Chester Beatty Numbers and Deuteronomy Codex

Dr. Martin Kauffmann (MK)

Assistant Librarian, Department of Special Collections and Western Manuscripts, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

The Junius Manuscript (alias The Old English Genesis, or The Caedmon Manuscript)

Dr. Herbert L. Kessler (HLK)

Professor of the History of Art, Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

The Sion Treasure Book Covers (Christ between Saints Peter and Paul)

The Rabbula Gospels

Richard A. Leson (RAL)

Zanvyl Krieger Curatorial Fellow, Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Armenian Gospelbook

Adolfo Roitman , Ph. D. (AR)

Curator of the Dead Sea Scrolls and Head of the Shrine of the Book, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

The Dead Sea Scrolls: Isaiah Scroll, Manuscript B

ca. 600 B.C.E.

Ezra the Scribe reconstructs the Hebrew scriptures destroyed by the Babylonians

ca. 250 B.C.E.

Formation of the Septuagint commences; according to legend, with the Hebrew Torah translated into Greek in Alexandria at the command of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 B.C.E.)

ca. 3 B.C.E.

Birth of Christ

ca. 30 C.E.

Crucifixion of Christ

ca. 50–60

First Christian texts (some of the Pauline Epistles) written

ca. 65–70

Gospel of St. Mark composed

ca. 80–90

Gospels of St. Matthew and St. Luke, and Acts of the Apostles composed

ca. 85–95

Gospel of St. John composed

late 1st century

Other letters composed (of James, of Peter, of John, to the Hebrews)

ca. 95

Apocalypse / Revelation of John composed

ca. 100

Council of Jamnia determines the canonical text of the Hebrew Bible, known as the “Masoretic” text

ca. 125

Earliest surviving manuscript of a gospel written (St. John, known from fragments)

second century

Old Testament books start to be individually translated from Hebrew into Syriac

first half 2nd century

Christian writings—letters, gospels, and apocalypses—multiply; Pauline Epistles circulate as a collection

ca. 180

Irenaeus, bishop of Lyon, asserts the primacy of the four gospels (St. Matthew, St. Mark, St. Luke and St. John); Tatian, a Syrian, produces the Diatessaron, a single narrative drawn from the gospels and additional material

early 3rd century

Origen of Alexandria compiles a comparative edition of the Old Testament in Hebrew and Greek, the Hexapla

late 3rd century

St. Anthony retreats into the eastern desert of Egypt, beginning a trend towards ascetic desert monasticism

303

Emperor Diocletian orders the destruction of Christian books during the “Great Persecution”

312

Constantine sees a vision of the Cross and triumphs at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge

313

Edict of Milan: Emperor Constantine grants freedom of worship throughout the Western Empire

early 4th century

Armenia becomes the first nation to adopt Christianity as its state religion; Gregory the Illuminator ordained bishop of Armenia (ca. 314); Christianity introduced to Ethiopia from Egypt

324

Constantine defeats Emperor Licinius and reunites the Empire’s two halves

325

Council of Nicaea, the first ecumenical council, condemns Arianism

330

Constantinople (now Istanbul) founded by Constantine as a bridgehead between East and West

332

Constantine commissions Bishop Eusebius to supply the churches he has founded in Rome with complete Bibles

ca. 337

Georgia accepts Christianity as its state religion

mid–4th century

Codex Sinaiticus, the earliest surviving complete Christian Bible, is made in Caesarea

363

Council of Laodicea lists 26 canonical books for reading in church (omitting Revelation)

ca. 372

St. Martin of Tours introduces monasticism to Europe

381

First Council of Constantinople declares that that city exerts an equal authority in the East to that of Rome in the West

ca. 382

St. Jerome enters the service of Pope Damasus and is commissioned to produce a Latin edition of the Bible—the Vulgate

383

Death of Ulfilas, “Apostle to the Goths,” who translated the Bible into the Gothic language

392

Emperor Theodosius bans pagan worship, and Christianity effectively becomes the state religion of the Roman Empire

393

Council of Hippo and Council of Carthage (397) both name the 27 books of the New Testament we know today

ca. 400

Roman Empire begins to contract

5th century

Syriac translations of Old Testament and New Testament books combined to form the Peshitta,the standard text for Syriac-speaking Churches

early 5th century

Greek alphabet adapted by the missionary St. Mesrob to produce those of Armenia and Georgia

431

Council of Ephesus condemns the views of Nestorius on the nature of Christ; Bishop Palladius is sent from Rome to believers in southern Ireland

451

Council of Chalcedon condemns Monophysitism (the belief that Christ has only divine nature) and establishes five patriarchates—Constantinople, Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem

ca. 460–90

St. Patrick’s mission from the northern British Church to Ireland

548–65

Emperor Justinian founds the monastery now known as St. Catherine’s on Mt. Sinai

ca. 529

St. Benedict founds the monastery of Montecassino in Italy

563

St. Columba leaves Ireland on voluntary exile to evangelize the Picts and the English, and founds the monastery of Iona in western Scotland

580

Death of Cassiodorus, founder of the monastery called the Vivarium in southern Italy

588

Patriarch John IV of Constantinople declares himself Ecumenical Patriarch, a title still retained by the leader of the Greek Orthodox Church

597

Death of St. Columba; Pope Gregory the Great sends a Roman mission led by St. Augustine to Britain to convert the Anglo-Saxons

599

Pope Gregory the Great sends a legate bearing gifts to Sinai

604

Death of Pope Gregory the Great

ca. 610

The Prophet Muhammad begins preaching in Mecca

615–17

Paul of Tella makes the Syrohexapla, a translation into Syriac of Origen’s Hexapla

635

Monastery of Lindisfarne is founded in northeast England

ca. 641

Islamic conquest of eastern and southern Mediterranean complete

687

Death of St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne

716

Abbot Ceolfrith of Wearmouth–Jarrow sets off for Rome in retirement, taking one of three great complete bibles made by his community as a gift for the pope

720s–787

Period of Iconoclasm in Byzantium

754/5

Death of St. Boniface, “Apostle to the Germans,” at Dokkum (now in The Netherlands)

735

On his deathbed the scholar Bede, a monk at Wearmouth–Jarrow, translates St. John’s Gospel into English

787

Council of Nicaea reinstates the use of images in Byzantium

793

Viking raids on Europe commence with the sacking of Lindisfarne

late 8th century

Theodulf of Orléans asserts the primacy of the word over images in his Libri carolini

800

Emperor Charlemagne crowned in Rome, solemnizing the creation of a Carolingian Empire; Abbot Alcuin of Tours completes a single-volume edition of the Vulgate Bible, copied throughout the Carolingian Empire

814–43

Resurgence of iconoclasm in Byzantium

869

Byzantine Emperor Constantine sends St. Cyril as a missionary to the Slavs; Cyril invents the Glagolitic alphabet from which Cyrillic is descended

ca. 950–60

Aldred glosses the Lindisfarne Gospels into Old English—the oldest surviving translation of the Gospels into English

ca. 962–1056

Ottonian Empire succeeds the Carolingian in Europe

aedicule

From the Latin for “miniature house.” A niche or opening framed by two columns, an entablature, and usually a pediment.

antiphonal

A servicebook containing the sung portions of the Divine Office. During the Middle Ages they were often large (so that they could be used by a choir) and included decorated and historiated initials, depicting saints and key events of the liturgical year. Hymns are usually contained in a separate volume.

apocalypse

The biblical book known in the Protestant tradition as the Book of Revelation. During the Middle Ages, Apocalypse manuscripts were produced in Latin and Anglo-Norman versions often accompanied by commentaries, and sometimes with picture cycles. They became particularly popular from the tenth century onwards, although some earlier manuscript examples and picture cycles are known.

apocryphal

From the Greek for “hidden things.” Used of texts of disputed canonical status.

apotropaic

Serving to ward off evil.

bibliotheca

Greek, literally a “box for storing books.”

bookroll

A manuscript, generally consisting of several sheets of papyrus pasted together, on which the writing is in many columns written side by side, with lines running parallel to the length of the papyrus.

book-shrine

In Coptic Egypt and in Ireland (where it was called a cumdach), a box designed to protect and exalt a sacred manuscript. It was made of wood covered with decorative metalwork and sometimes precious stones.

breviary

A servicebook containing the texts necessary for the celebration of the Divine Office. During the high Middle Ages it might be adorned with decorated and historiated initials and more luxurious copies contain miniatures depicting biblical scenes or the performance of the Office.

canon

A list of sacred or other writings acknowledged as genuine and/or authorized for standard use.

canon table

A system indicating the concordance of passages among the gospels, devised in the fourth century by Eusebius of Caesarea. Gospel passages are numbered, generally in the margins, in accordance with what are termed “Ammonian sections”. (The division of passages is usually ascribed to Ammonius of Alexandria, ca. 220, although he may merely have inspired Eusebius to create his own divisions.) These numbers are also arranged in columnar form to create the tables, which are often set within ornamental surrounds of an architectural character. Canon tables were generally placed at the beginning of a volume and were popular in gospelbooks, whole bibles, and New Testaments, especially during the early Middle Ages.

canticle

A song derived from the Bible.

capitula (sing. capitulum)

Latin. Lists of chapters, often found preceding the gospels.

Carolingian

A dynasty of Frankish kings (751–962), whose empire expanded under Charlemagne (emperor from 800) and came to embrace much of northern Europe (excluding Britain and much of Spain and Italy). Charlemagne and his successors promoted the Carolingian cultural renaissance and ecclesiastical reform, which resulted in the scholarly revision of sacred texts, the production of large illuminated bibles, and the development of a new script, caroline minuscule. In 843, the empire was divided into three parts by the Treaty of Verdun and the Ottonian dynasty assumed imperial power in 962.

caroline

Of or relating to Charlemagne or the Carolingian dynasty and its culture.

carpet page

An ornamental page, without text, the patterns on which resemble those of an Oriental carpet. It sometimes incorporates a cross in its design. Such pages generally separate the four gospels in a manuscript, or might serve to introduce the book. They are perhaps of Coptic origin.

cartonnage

A material made of layers of gummed linen or waste papyrus soaked in plaster.

cartulary

A collection of charters or deeds, especially relating to the property of a monastery or other large estate.

Chi-rho

A Christian symbol consisting of the first two letters of Christ’s name in Greek, chi and rho.

chrysography

From the Greek, literally “writing in gold.” The technique used powdered gold (or silver), mixed with glair or gum to create an ink; when dry, the ink was usually burnished. Gold leaf was also sometimes used. Such writing on parchment is known from the Early Christian period and from the sixth century was often used on pages stained purple.

codex (pl. codices)

From the Latin caudex, for tree bark. A book consisting of sheets of papyrus or parchment stacked and sewn along one side. Originating in the first century, the codex was popular among Christians for its portability and ease of use and eventually supplanted the bookroll as the favored vehicle for literary texts after the Christianization of the Roman Empire.

codicology

The study of the physical structure of books, including the number of leaves used in a gathering, the way in which they are pricked and ruled, and how the book is sewn and bound. This examination can shed considerable light on a book’s method of production, place of origin, and provenance, and can help to reconstruct its original appearance.

colophon

A term originally meaning the label on the outside of a bookroll, identifying its contents. In the Middle Ages, however, it denotes an inscription recording information relating to the circumstances of a book’s production, which might include the place of manufacture and the people involved and, less frequently, the date. Colophons are generally located at the end of a book.

colophon decoration

A late Roman practice of drawing attention to titles, colophons, and the like by framing them with patterns formed by dots and commas.

Coptic

A language written in the Greek alphabet but descended from ancient Egyptian; the ancient Christian Church of Egypt; appertaining to the Christian inhabitants of early medieval Egypt.

cross-carpet page

See carpet page

cursive

A rapidly written script, with many letters joined together and sometimes including loops.

display script

Decorative, sometimes colored, script often used to emphasize the opening of a major section of text.

Divine Office

The canonical prayers and psalms recited daily by priests, monks, and nuns at certain prescribed hours (matins, lauds, prime, tierce, sext, none, vespers, compline).

Early Christian

The period from apostolic times to around 600, when Pope Gregory the Great established a strong, independent Western Church. It overlapped with Late Antiquity and began the transition into the Middle Ages.

epistolary

A servicebook containing readings from the epistles (the letters in the New Testament) for the Mass, arranged according to the liturgical year.

estrangela

From the Greek for “rounded”; in Syriac, literally “to write the Gospels.” A formal script used to write the Syriac language, running from right to left.

euchologion

A servicebook containing prayers, parts of services, and biblical passages for use in the performance of the liturgy.

evangelary/evangelistary

See lectionary

evangelist

portrait A depiction of one of the “authors” of the canonical gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—perhaps identified by his accompanying symbol (a man or angel, lion, ox, and eagle respectively). The symbols could also be depicted alone.

exegete

A person who explains or interprets a written work.

explicit

From the Latin explicitus, for “unrolled.” A title marking the closing of a major section of text, sometimes written in display script.

floruit

From the Latin for “flourished.” The period of time during which a person (whose birth and death dates are not known) was productive.

Frank

A member of one of a number of Germanic tribal federations, who began to invade Roman territory in the third century C.E. and established an empire in northern Europe from the fifth century onward. See also Carolingian, Merovingian

gathering

The booklets or “quires” of which a book is formed. Initially, single sheets of papyrus were cut square, stacked, folded at the middle, and then stitched together along the fold. A single gathering could comprise as many as fifty sheets. Many early codices consisted of single gatherings with a large number of sheets, but later multiple gatherings with fewer sheets were stacked and sewn together, especially after parchment or vellum replaced papyrus.

Glagolitic

A language with a 40-character Greek-based alphabet, the invention of which is ascribed to Saint Cyril (ca. 827–869) and his companion Saint Methodius. It formed the basis of Cyrillic script.

gloss

A word or words commenting on, clarifying, or translating those of the main text. Glosses were often written in the margins or between the lines.

gospel

From Old English godspell, “good news.” The message of a religious teacher; in particular the story of Christ’s life, teachings and Resurrection as narrated in one of the canonical gospels (attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), the first four books of the New Testament.

gospelbook

A book containing the full text of the canonical gospels, often accompanied by introductory matter such as the prefaces of Saint Jerome, Eusebius’s canon tables, and chapter lists (capitula). From the sixth or seventh century on, carpet pages, incipit pages, Chi-rho pages, evangelist portraits or symbols, and other illustrations appeared in gospelbooks. From the late eighth century, gospelbooks were partially replaced in liturgical use by lectionaries.

half-uncial

A script derived from uncial. In Ireland and Britain it developed independently to form the basis of Insular formal book-script.

Hebrew Names

A list, often found prefacing Irish/Celtic gospelbooks, explaining the Hebrew names contained in the biblical text. Saint Jerome regularized these in accordance with the Hebrew originals.

historiated initial

A large letter framing a pictorial subject that illustrates the text.

incipit

The opening of a major section of text, sometimes marked by a whole decorative page, embellished with a large initial or monogram and display script.

incunable

A book printed before 1501.

Insular

Referring to the culture of Britain and Ireland from around 550 to 850, which fused Celtic, Germanic, Antique, Early Christian, and Mediterranean elements to form something new. Developments in book production first occurred in sixth- to seventh-century Ireland, then in England and Scotland, where Irish influence mixed with Germanic and Pictish styles to produce Hiberno-Saxon art. Southern England produced its own distinctive styles of decoration and script, while other areas such as Wales preserved their late Roman legacy. A characteristic feature of Insular books is the integration of decoration, script, and text. Insular art and learning in turn helped stimulate the Carolingian renaissance.

Karaite

A Jewish sect originating in eighth-century Baghdad. Their belief that the Hebrew Bible was the sole source of religious law led to a concentration on the close study of the text of the Bible.

lectionary

A servicebook containing readings for the Mass, arranged according to the liturgical year; also known as an evangelary or pericope book. The lectionary became increasingly popular from the Carolingian period on.

liturgy

The rites, observances, or procedures prescribed for public worship and for the public prayer-life of the Church. At the core of Christian liturgy are the Mass and the Divine Office.

Masoretic

text Canonical text of the Hebrew Bible, as determined at the Council of Jamnia (ca. 100 C.E.). The Masorah, a body of notes on the traditions of the text, was compiled 600–900 C.E. by Jewish scribes called the Masoretes.

Mass

The celebration of the Eucharist (the consecration and consumption of bread and wine in commemoration of the Last Supper).

Merovingian

A dynasty of Frankish kings (480–751), predecessors of the Carolingians.

minuscule

A script in “lower case” (rather than capital) letters, with longer strokes called ascenders and descenders that extend above and below the body of the letter (as in d and q). Caroline minuscule, developed in Carolingian scriptoria in the late eighth century, was used even for more formal manuscripts that earlier would have been written in capitals, uncials, or half-uncials.

missal

A servicebook containing the texts necessary for the performance of the Mass (including chants, prayers, and readings), together with ceremonial directions. Introduced in the early Middle Ages, it eventually supplanted the sacramentary,gradual, evangelary, and epistolary, which had previously been used together.

Monarchian prologue

A prologue to each of the gospels, attributed to the Spanish theologian and heretic Priscillian (died 386). It summarizes the authority from which each evangelist received his gospel’s teachings.

Mozarab

A Christian inhabitant of Spain under Muslim rule.

neume, neumatic

An early form of musical notation used for plainsong in the Middle Ages. The marks, written above the text rather than on stave lines, indicate the general shape of the music but not precise notes or rhythms.

ogam

An alphabet (perhaps of Irish origin but inspired by Roman script) used by the Celts for short inscriptions. Letters consist of straight or diagonal marks written along or across a single line.

orthography

Spelling, study of the variants of which can help locate the origins of a manuscript, or identify a scribe.

Ottonian

A ruling dynasty in Germany (919–1024), whose empire succeeded that of the Carolingians (from 962).

palimpsest

From the Greek palimpsestos, “scraped again.” A reused document from which the original writing might be erased by washing (in the case of papyrus) or scraping, with pumice or a knife (in the case of parchment), before being written over. Sometimes the underlying text can be read in ultraviolet light or using electronic image-enhancing techniques.

pandect

From the Greek, “all receiver.” A single volume containing the complete biblical text.

papyrus

(pl. papyri) A writing support material made from a species of rush that grows in marshes along the River Nile.

parchment

From Pergamon (Bergama in modern Turkey), an early production centre. A writing support material made from prepared sheep and goat skin. The skin was defleshed, stretched, and scraped, and might be treated with pumice and whitened with chalk before being cut to size. Parchment supplanted papyrus as the most popular writing support material in the fourth century, and was itself largely replaced by paper in the sixteenth century with the rise of printing, thought it remained in use for certain high-grade books. Parchment is the term used generically in the present work to indicate prepared membrane. See also vellum.

paschal

Relating to Passover or Easter.

paten

The plate used to hold the host (consecrated bread) during the celebration of the Eucharist.

patristic

Relating to texts written by the Church Fathers or other Early Christian writers whose authority was particularly respected in later periods. Well-known patristic authors include Saint Augustine, Saint Jerome, and Saint John Chrysostom.

pentecost

From the Greek for “fifty.” In Judaism, the fiftieth day after Passover; in Christianity, the descent of the Holy Spirit to the apostles and their speaking in tongues.

psalter

A volume containing the Psalms. Medieval psalters were used in the liturgy and for private devotion. Depictions of King David, author of many of the Psalms, frequently introduce the psalter, which might also feature a calendar, canticles, creeds, a litany of the saints, and prayers. Byzantine psalter illustration exerted an important influence on the West.

pyx

A container for the host (bread consecrated in the Eucharist).

quire

See gathering

rubric

From the Latin rubrica, “red.” A title, chapter heading, or instruction, often written in red ink, that is not part of the text but which helps to identify its components or instructs on their use.

rune

A letter from one of a number of alphabets used by the Germanic tribes of northern Europe before Christianization. Some runes were combined with the Latin alphabet in written Old English.

Sassanian

Of the Sassanid dynasty (224–651 C.E.) in Iran, Iraq, and neighboring areas.

scriptorium

A writing room, usually (but not exclusively) in a monastery or church, where books are made.

scriptura continua

Latin. Writing in which the letters are written one after the other without spaces between the words. This was usual during Antiquity, until Insular scribes introduced word-separation and more systematic punctuation, which was in turn developed further in Carolingian scriptoria.

scroll

See bookroll

stylus

A pointed tool, generally of metal or bone, used for writing on wax tablets, and also for pricking and ruling manuscripts.

treasure-binding

An elaborately decorated, often bejeweled, front cover for a codex, indicating the value of the text within.

trishagion

A hymn used in the Mass, from Isaiah 6:3 and Revelation 4:8: “Holy, Holy, Holy.”

troper

A servicebook containing tropes, that is, musical and textual additions to the chants of the Mass or Divine Office, sung by a soloist. Tropers are known from the early Middle Ages onward.

typology

An interpretive system in Christian thought, designed to prove that the New Testament is a fulfillment of the Old. The sacrifice of Isaac, for example, foretells the Crucifixion; David is a type of Christ; and the stories of Daniel in the lions’ den and Jonah and the whale prefigure Christ’s Passion and Resurrection. Encountered during the early Middle Ages, and favoured by Saint Jerome, typological juxtapositions become increasingly frequent in art from the eleventh century on.

uncial

A formal script with letters based on Roman capitals but with more rounded forms. It was introduced in the third century C.E.

vellum

A writing support material made from calfskin. Uterine vellum, the skin of stillborn or very young calves, is particularly fine and white in appearance, but was rarely used. The term is often used generally to indicate prepared membrane. See also parchment

vernacular

From the Latin for “vulgar.” A regional language, as distinct from an international literary language, such as Latin and Greek. Throughout the Middle Ages biblical texts were only gradually translated into the vernacular, although development of Western vernacular literacy began at least as early as the sixth to eighth century in Ireland and Anglo-Saxon England.

Note: Descriptions of the manuscripts on this site are taken from the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000 (Freer/Sackler, 2006). See the catalogue for scholarly essays, a full bibliography, and comprehensive information on all the works in the exhibition.

Aland, K., 1976. Repertorium der griechischen christlichen Papyri, vol. 1, Biblische Papyri: Altes Testament, Neues Testament, Varia, Apokryphen. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter. [2d ed., 1989]

Alexander, J. J. G., 1978. Insular Manuscripts: 6th to the 9th Century. London: Harvey Miller.

Alexanian, J. M., 1990–91. “The Text of the Oldest Armenian Gospel Manuscript in America: A Reappraisal of Walters Art Gallery MS 537,” Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies 5:55–64.

Alexidze, Z., and others, 2005. Catalogue of Georgian Manuscripts Discovered in 1975 at Saint Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai. Athens: Greek Ministry of Culture and the Mount Sinai Foundation.

Amtower, L., 1993. “Some codicological considerations in the interpretation of the Junius poems,” English Language Notes 30:4–10.

Balicka–Witakowska, E., 1997. La Crucifixion sans crucifié dans l’art éthiopien: recherches sur la survie de l’iconographie chrétienne de l’Antiquité tardive, Bibliotheca nubica et aethiopica 4. Warsaw: Zas Pan.

Barthélemy, D. and J. T. Milik, 1955. Discoveries in the Judean Desert, vol. 1, Qumran Cave I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beit–Arié, M., C. Sirat, and M. Glatzer, 1997. Codices hebraicis litteris exarati quo tempore scripti fuerint exhibentes 1. Monumenta Palaeographica Medii Aevi, Series Hebraica. Turnhout: Brepols.

Bergman, R. P., 1980. The Salerno ivories: ars sacra from medieval Amalfi. Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press.

Bischoff, B., 1957. “Die Kölner Nonnenhandschriften und das Skriptorium von Chelles,” in Karolingische und ottonische Kunst. Werden, Wesen, Wirkung. VI. internationaler Kongress für Frühmittelalterforschung, 1954, 395–411. Wiesbaden: F. Steiner. [Reissued in expanded form in Bischoff, 1966–81, 1:16–34.]

Blum, P., 1976. “The cryptic creation cycle in MS Junius XI,” Gesta 15:211–26.

Boak, A. E. R., 1959. “The Building of the University of Michigan Papyrus Collection,” Michigan Alumnus Quarterly Review 66, no.10 (Autumn): 35-42.

Boyd, S. A., and M. M. Mango, eds., 1992. Ecclesiastical Silver Plate in Sixth–Century Byzantium, Papers of the Symposium Held May 16–18 at the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore and Dumbarton Oaks. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Broderick, H., 1983. “Observations on the method of illustration in MS. Junius 11 and the relationship of the drawings to the text,” Scriptorium 37:161–77.

Brown, M. P., 2001. “Anglo-Saxon Manuscript Production: Issues of Making and Using” in Anglo-Saxon Literary Culture, ed. P. Pulsiano and E. Traherne. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

—, 2001a. “Female book-ownership and production in Anglo-Saxon England: the Evidence of the Ninth-Century Prayerbooks,” in Lexis and Texts in Early English: Papers in Honour of Jane Roberts, ed. C. Kay and L. Sylvester, 45-68. Amsterdam: Brepols.

—, 2006. How Christianity Came to Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Lion Hudson.

Buchthal, H. and O. Kurz, 1942. A Handlist of Illuminated Oriental Christian Manuscripts, Warburg Oriental Studies 12. London: Warburg Institute. [2nd. ed., 1969.]

Canberra, 2001. Treasures from the World’s Great Libraries [exhibition catalogue]. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

Cecchelli, C., ed., 1959. The Rabbula Gospels. Olten and Lausanne: Urs Graf.

Charlesworth, J. H., 1981. The New Discoveries in St. Catherine’s Monastery. A Preliminary Report on the Manuscripts. Winona Lake, Ill.: American Schools of Oriental Research.

Choat, M. 2006. “The Unknown Work on Prophecy in the Freer Minor Prophets Codex,” The Freer Biblical Manuscripts: Fresh Studies of the Greek Biblical Manuscripts Housed in the Freer Gallery, ed. L. Hurtado. Atlanta: Society for Biblical Literature Publications.

Chojnacki, S., 2000. Ethiopian Icons: Catalogue of the Collection of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa University. Milan: Skira.

Clark, K. W., 1952. Checklist of Manuscripts in St Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai. Microfilmed for the Library of Congress, 1950. Washington, D. C.: Library of Congress.

de Hamel, C., 1986. A History of Illuminated Manuscripts. Oxford: Phaidon. [2nd ed., London: Phaidon, 1994.]

Doane, A. N., 1978. Genesis A. A new edition. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

—, 1991. The Saxon Genesis: An edition of the West Saxon Genesis B and the Old Saxon Vatican Genesis. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Evans, J. M., 1963. “Genesis B and its background,” Review of English Studies 14:1–16, 113–23.

Fischer, B., 1971. “Die Alkuin-Bibeln” Die Bibel von Moutier–Grandval: British Museum Add. Ms. 10546. Bern: Verein Schweizerischer Lithographiebesitzer.

—, 1985. Lateinische Bibelhandschriften im frühen Mittelalter, Vetus Latina. Aus der Geschichte der Lateinischen Bibel 11. Freiburg: Herder.

Fitzgerald, W., 1992. Ocelli Nominum: Names and Shelf Marks of Famous / Familiar Manuscripts. Toronto: University of Toronto / Pontifical Insititute of Mediaeval Studies.

Franz, G., ed., 1985. Trevirensia: Beiträge zur Trierer Bibliotheksgeschichte. Wiesbaden: Reichert.

Gameson, R. G., 2003. The Stockholm Codex Aureus, Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile 28. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde & Bagger.

Gardthausen, V. E., 1886. Catalogus codicum graecorum Sinaiticorum. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Garitte, G., 1956. Catalogue des Manuscrits Géorgiens Littéraires du Mont Sinai, Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, vol. 165, Subsidia tom. 9. Louvain: L. Durbecq.

J. Paul Getty Museum, 1991. A Thousand Years of the Bible: Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts [exhibition catalogue]. Malibu, Calif.: J. Paul Getty Museum.

Goldschmidt, A., 1914. Die Elfenbeinskulpturen aus der Zeit der Karolingischen und Sächsischen Kaiser, vol. 1. Berlin: Cassirer. [Reissued Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 1969]

Gollancz, I., 1927. The Caedmon Manuscript of Anglo–Saxon Biblical Poetry [facsimile]. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gospel of Thomas, 1959. Coptic text ed. A. J. P. Guillaumont and others, Evangelium nach Thomas. Leiden: Brill.

Graf, G., 1944-53. Geschichte der christlichen arabischen Literatur, 5 vols., Studi e Testi 118, 133, 146, 147, 172. Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Grenfell, B. P. and Hunt, A. S., 1897. Logia Iesou. Sayings of Our Lord from an Early Greek Papyrus. London: Egypt Exploration Fund.

Günzburg, D. and V. Stassoff, 1886 and 1905. Ornementation des anciens manuscrits Hébreux de la Bibliothèque Impériale Publique de Saint–Pétersbourg. St. Petersburg, 1886 and Berlin: S. Calvary and Co., 1905. [Plates reissued in Narkiss, 1990]

Haelst, J. van, 1976. Catalogue des papyrus littéraires juifs et chrétiens. Paris: Sorbonne.

Hall, J. R., 1976. “The Old English epic of redemption: the theological unity of MS Junius 11,” Traditio 32:185–208.

Heldman, M. E., [1975]. “Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem in Ethiopia,” Proceedings of the First United States Conference on Ethiopian Studies, 1973, ed. H. G. Marcus, 43–60. East Lansing: African Studies Center, Michigan State University.

—, 1994. The Marian Icons of the Painter Fre Seyon: A Study of Fifteenth-Century Ethiopian Art, Patronage, and Spirituality. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Henderson, G., 1975. “The programme of illustrations in Bodleian MS Junius XI,” in Studies in Memory of David Talbot Rice, ed. G. Robertson and G. Henderson, 113–45. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Repr. in G. Henderson, Studies in English Bible Illustration 1:138–83. London: Pindar Press, 1985]

—, 1987. From Durrow to Kells, the Insular Gospel-books 650Ð800. London: Thames & Hudson.

Jagic, V., 1879. Quattuor evangeliorum codex glagoliticus olim Zographensis nunc Petropolitanus. Berlin: Weidmann. [Repr. Graz: Akademischer Druck– und Verlagsanstalt, 1954]

Kahle, P., 1959. The Cairo Geniza, 2nd ed. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Kamil, M., 1970. Catalogue of all Manuscripts in the Monastery of St. Catharine on Mount Sinai. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

Kenyon, F. G., ed., 1935–58. The Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri: Descriptions and Texts of Twelve Manuscripts on Papyrus of the Greek Bible, Fasc.V: Numbers and Deuteronomy, Text (London: Emery Walker, 1935); Fasc. V: Numbers and Deuteronomy, Plates (Dublin, Hodges Figgis, 1958).

—, 1939. Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts, 4th ed. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

Ker, N. R., 1957. Catalogue of Manuscripts Containing Anglo-Saxon. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Reissued with Supplement, 1990]

Kessler, H. L., 1977. The Illustrated Bibles from Tours. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Krapp, G. P., 1931. The Junius manuscript, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 1. London and New York: Routledge / Columbia University Press.